Published online Dec 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.13044

Peer-review started: August 31, 2022

First decision: October 12, 2022

Revised: October 30, 2022

Accepted: November 18, 2022

Article in press: November 28, 2022

Published online: December 16, 2022

Processing time: 99 Days and 19.4 Hours

Whipple’s disease is a rare systemic infection caused by Tropheryma whipplei. Most patients present with nonspecific symptoms, and routine laboratory and imaging examination results also lack specificity. The diagnosis often relies on invasive manipulation, pathological examination, and molecular techniques. These difficulties in diagnosing Whipple’s disease often result in misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatments.

This paper reports on the case of a 58-year-old male patient who complained of fatigue and decreased exercise capacity. The results of routine blood tests indicated hypochromic microcytic anemia. Results of gastroscopy and capsule endoscopy showed multiple polypoid bulges distributed in the duodenal and proximal jejunum. A diagnosis of small intestinal adenomatosis was initially considered; hence, the Whipple procedure, a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, was performed. Pathological manifestations showed many periodic acid-Schiff-positive macrophages aggregated in the intestinal mucosa of the duodenum, upper jejunum, and surrounding lymph nodes. Based on comprehensive analysis of symptoms, laboratory findings, and pathological manifestations, the patient was finally diagnosed with Whipple’s disease. After receiving 1 mo of antibiotic treatment, the fatigue and anemia were significantly improved.

This case presented with atypical gastrointestinal manifestations and small intestinal polypoid bulges, which provided new insight on the diagnosis of Whipple’s disease.

Core Tip: Whipple’s disease is a rare disease diagnosed by invasive manipulation. We reported on the case of a 58-year-old male patient who complained of fatigue and decreased exercise capacity. Results of gastroscopy and capsule endoscopy showed multiple polypoid bulges distributed in the duodenal and proximal jejunum. A diagnosis of small intestinal adenomatosis was initially considered; hence, the Whipple procedure, a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, was performed. Many polyglandular autoimmune syndromes-positive macrophages aggregated in the intestinal mucosa of the duodenum, upper jejunum, and surrounding lymph nodes. Based on comprehensive analysis of symptoms, laboratory findings, and pathological manifestations, the patient was finally diagnosed with Whipple’s disease.

- Citation: Chen S, Zhou YC, Si S, Liu HY, Zhang QR, Yin TF, Xie CX, Yao SK, Du SY. Atypical Whipple’s disease with special endoscopic manifestations: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(35): 13044-13051

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i35/13044.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i35.13044

Whipple’s disease is a rare disease caused by infection with the Gram-positive bacterium Tropheryma whipplei. Tropheryma whipplei can invade various organs and systems throughout the whole body, with the main lesions involving the digestive, joint, cardiovascular, nervous, respiratory, and other systems[1]. Therefore, the clinical manifestations of Whipple’s disease vary depending on the infected organs and systems. The clinical spectrum of Tropherym whipplei infection encompasses classical Whipple’s disease, chronic localized infections, acute infections, and asymptomatic carriage[2]. Routine laboratory and imaging examinations of patients with Whipple’s disease lack specificity, which makes the diagnosis difficult. The diagnosis methods, including quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), rely on biopsy samples including the small intestinal mucosa, lymph nodes, or cerebrospinal fluid, serous effusion, and other body fluids[3]. However, in clinical practice, the acquisition of tissue and humoral samples for Whipple’s disease diagnosis often relies on invasive manipulation, such as endoscopy and lymph node biopsy under ultrasound/contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) guidance, which cannot always be performed due to limited personnel and equipment in primary hospitals. At the same time, most health care institutions, even larger medical centers, usually do not possess laboratory conditions to test for Tropheryma whipplei. Consequently, Whipple’s disease is easily misdiagnosed or missed altogether. Several antibiotic families are effective in the treatment of Whipple’s disease, including tetracyclines, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, rifamycins, macrolides, phenicols, and glycopeptides[4], among others. The initial phase of an intravenous antibiotic is known to penetrate the blood–brain barrier. After antibiotic treatment of classic Whipple’s disease, rapid improvement and clinical remission are usually reported[1]. This paper reports on a case of Whipple’s disease with anemia as the initial manifestation. Initially, the patient was misdiagnosed with a neoplastic disease of the small intestine and received surgical treatment with the Whipple procedure. The patient was finally diagnosed with Whipple’s disease by the pathological results of postoperative specimens. The aim of this report is to draw attention to the various clinical manifestations, especially the endoscopic features of Whipple’s disease, and to supply more knowledge for the differential diagnosis of Whipple’s disease.

A 58-year-old male patient was admitted to the Gastroenterology Department of China-Japan Friendship Hospital due to fatigue and decreased exercise capacity of unknown cause for more than 3 mo.

Symptoms lasted more than 3 mo without palpitations, dizziness, hematemesis, hematochezia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, jaundice, joint pain, or poor physical activity. The patient had not received diagnosis and treatment before. The above symptoms worsened 3 wk prior to hospital admission, and hemoglobin was detected at 80 g/L at a local hospital, indicating hypochromic microcytic anemia. Other laboratory results included a ferritin level of 146.5 µg/L (normal reference range: 30.00-400.00 µg/L), folic acid level of less than 1.36 nmol/L (normal reference range: 8.81-60.70 nmol/L), normal liver and kidney function tests, negative tumor marker tests, and negative fecal occult blood test. Gastroscopy showed scattered mucosal bulges with smooth surfaces in the descending part of the duodenum, and no apparent abnormalities were seen in the remaining parts. However, biopsy and pathological examination were not completed because the patient could not tolerate the gastroscopic inspection. The diagnosis at the local hospital was established as "cause of anemia to be investigated, descending duodenal adenomatosis?", and oral iron, folic acid, and other drugs were given for treatment.

The patient underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery 17 years ago due to myocardial infarction.

The patient engaged in cattle and sheep breeding over the past 20 years.

Vital signs were stable, and the physical examination was unremarkable except for a pale skin and conjunctiva.

Routine blood tests after hospital admission showed a hemoglobin level of 95 g/L, average red blood cell volume of 69.3 fL, average hemoglobin content of red blood cells of 19.7 pg, reticulocyte count of 1.91% (normal reference range: 0.5%-1.5%), and platelet count of 287 × 109/L. The nutritional anemia tests revealed a ferritin level of 52.2 µg/L (normal reference range: 23.90-336.20 µg/L) and folic acid level of 42.96 nmol/L (normal reference range: 7.00-45.1 nmol/L). Liver and kidney function and tumor marker tests were in normal ranges, and fecal occult blood results were still negative.

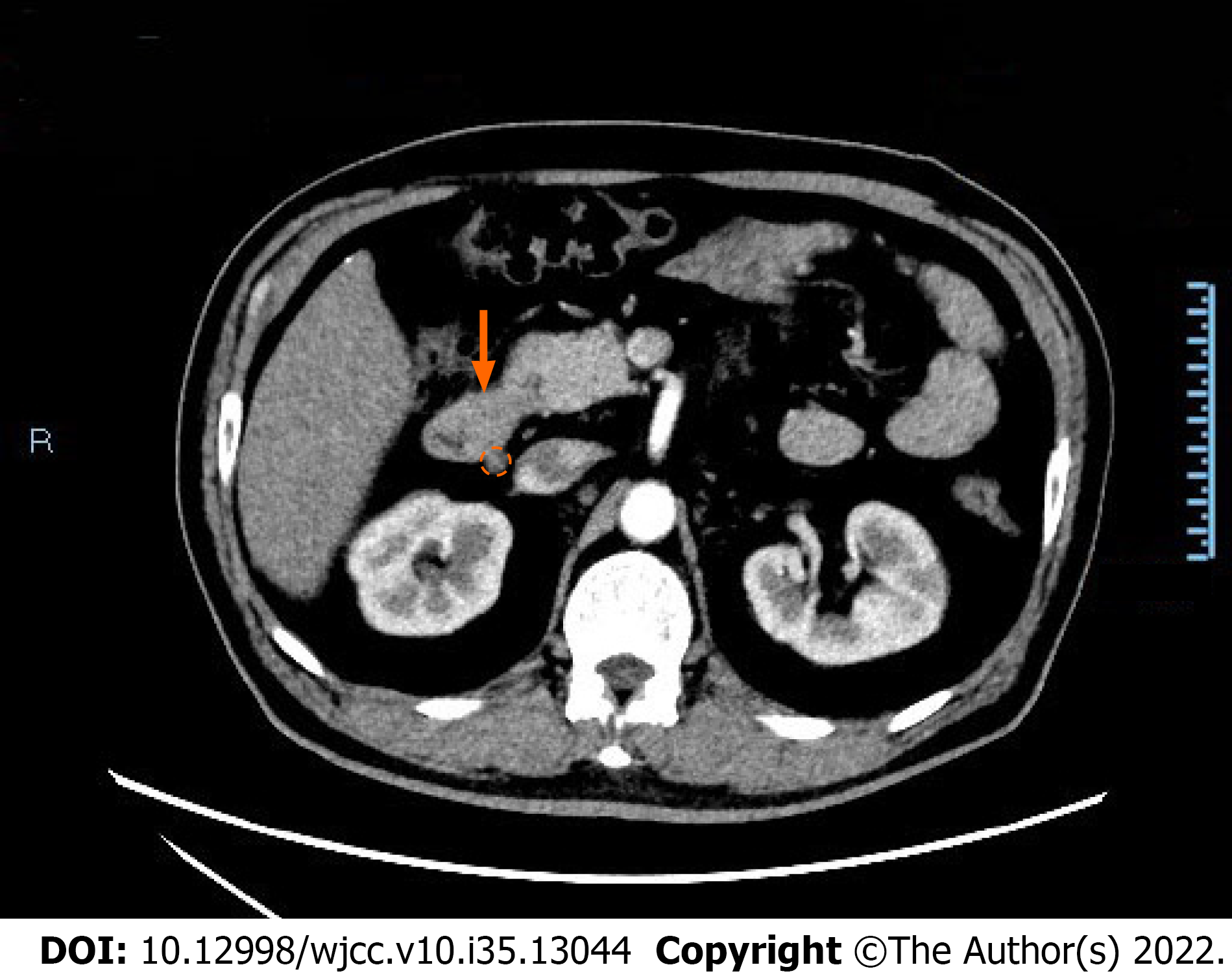

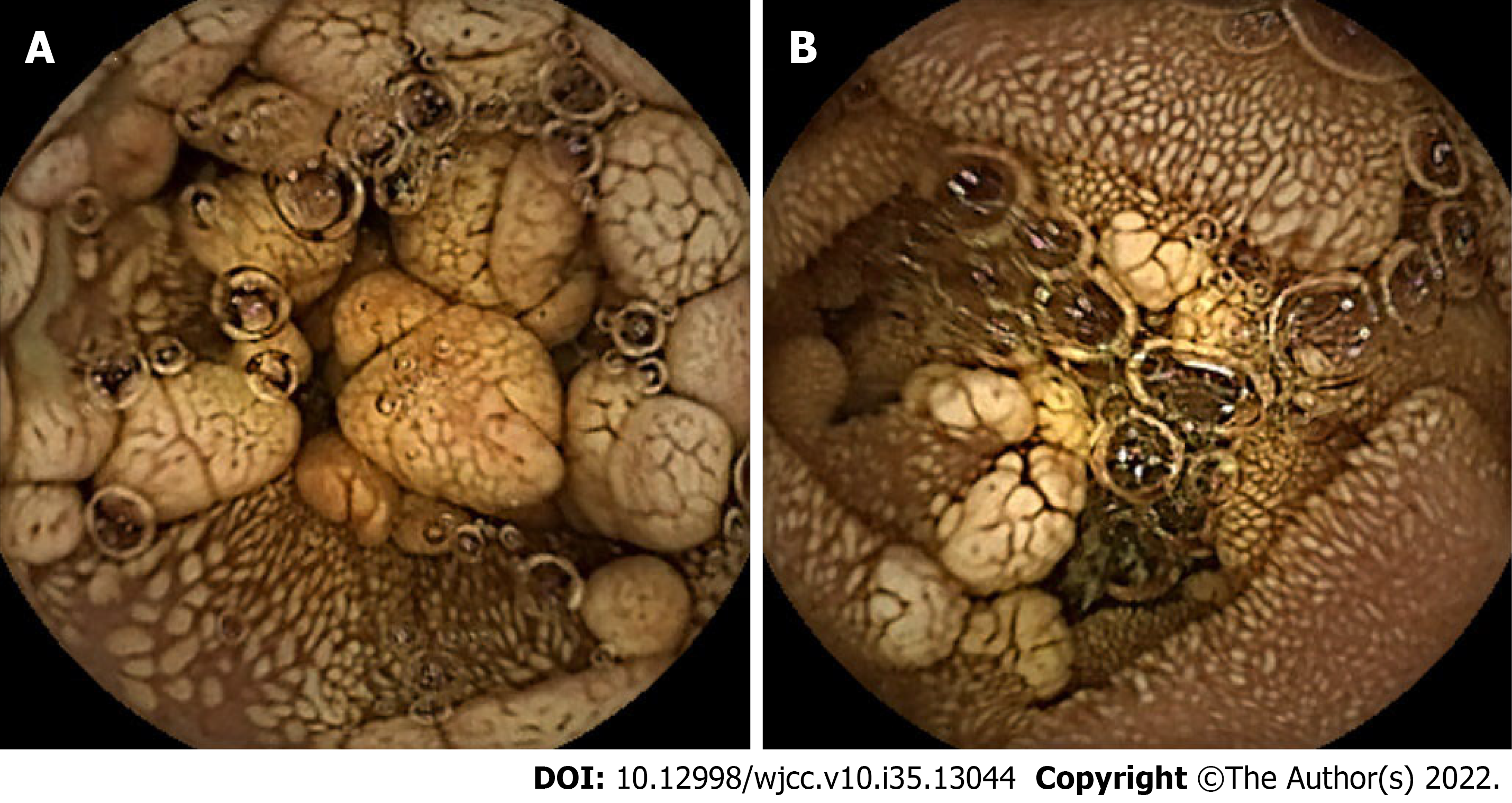

CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed thickening of the wall of the descending duodenum with adjacent enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 1). Physicians observed chronic nonatrophic gastritis by gastroscopy, during which the patient complained of chest pain and dyspnea, thus the duodenal bulb could not be observed further. No abnormalities were observed in colonoscopy. Capsule endoscopy showed multiple polypoid bulges in the duodenum and proximal jejunum (Figure 2).

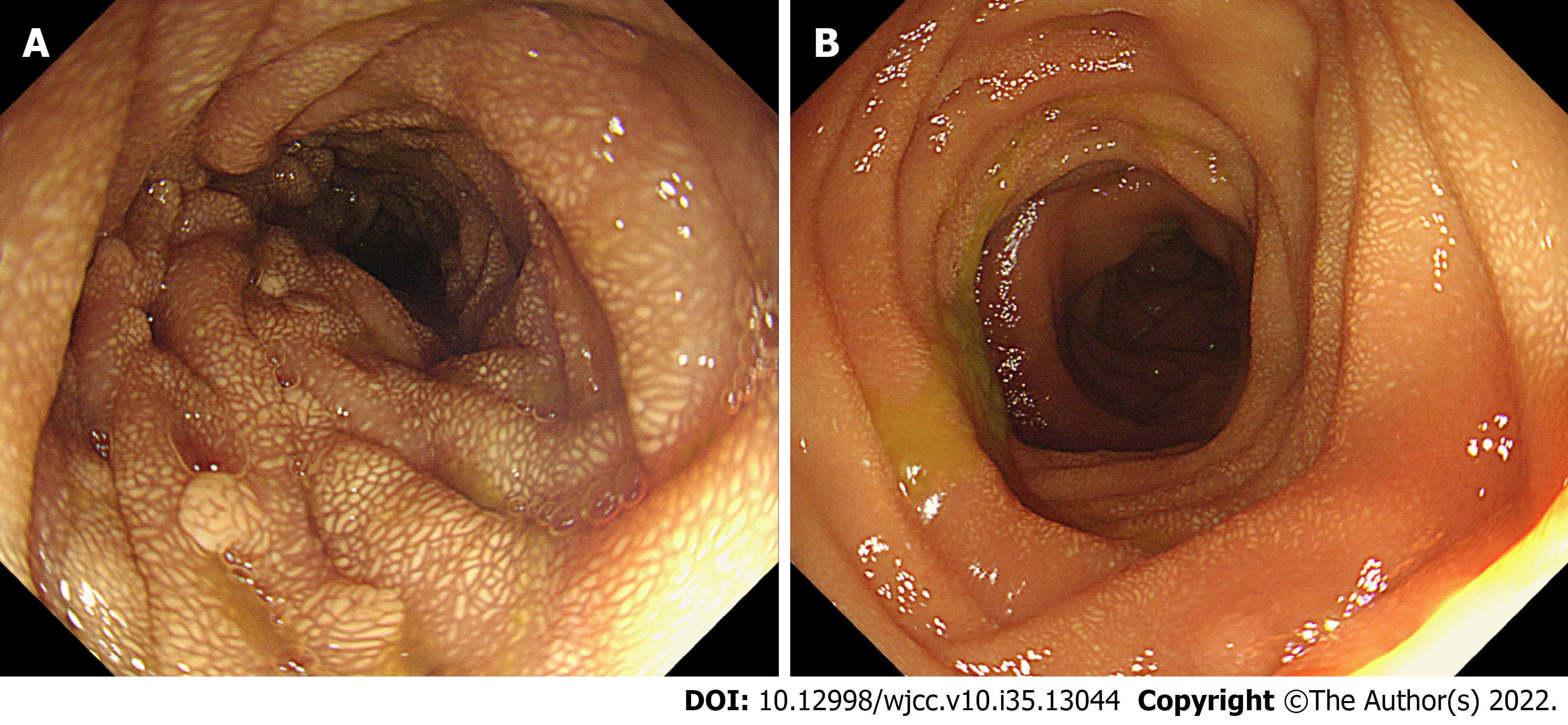

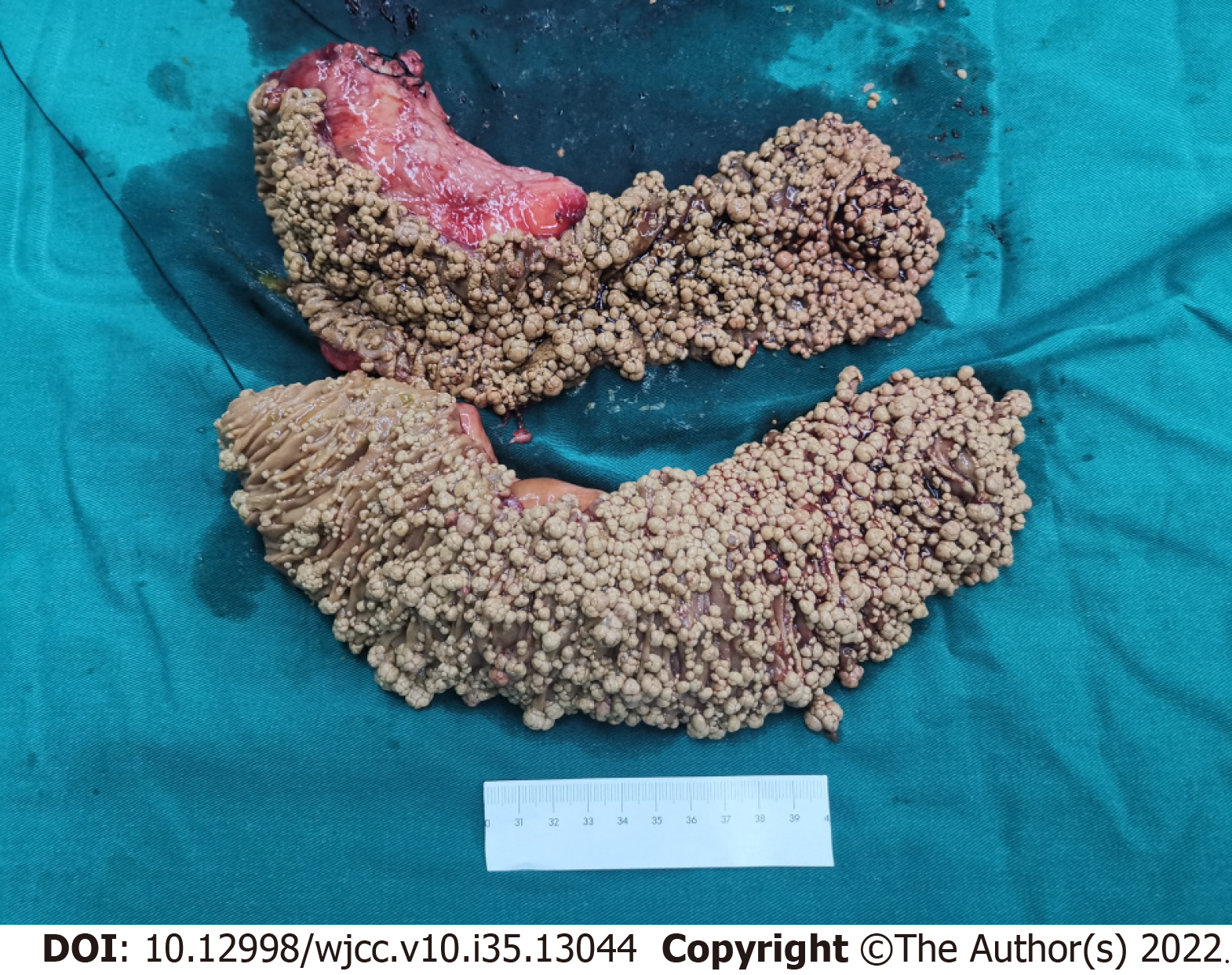

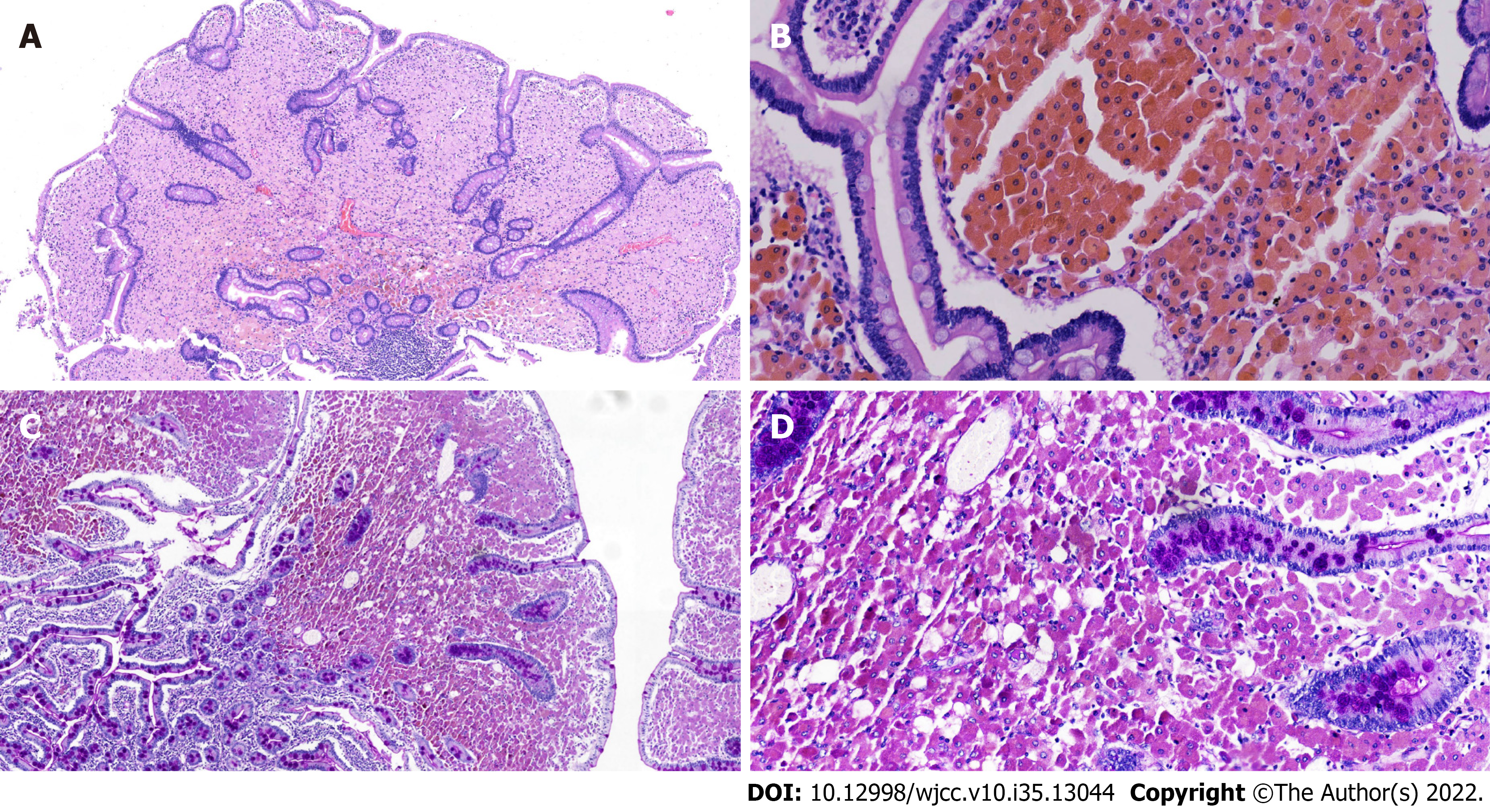

After consultation with the general surgeon, a diagnosis of small intestinal adenomatosis was considered a priority. Informed consent was obtained from the patient to perform a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure). The gallbladder, duodenum, head of the pancreas, and proximal jejunum (approximately 40 cm) were removed. During the operation, multiple lymph nodes at the root of the mesentery were enlarged and fused into masses, but no evidence of tumor cells was found in the frozen pathological examination. Subsequently, the endoscope was inserted from the broken end of the proximal jejunum to the anal side, and multiple polypoid bulges were still found along the proximal 20 cm intestinal segment (Figure 3); however, the number of bulges decreased gradually. Therefore, an additional 20 cm of the proximal jejunum was removed. Finally, biliary enterostomy, pancreatic enterostomy, and gastrointestinal anastomosis were performed successively. Upon gross inspection, the mucosal surface of removed small intestine (duodenum and proximal jejunum) specimens was covered with grayish-yellow polypoid bulges of various sizes ranging from a needle tip to 2 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm (Figure 4). Pathological manifestations showed that many macrophages were aggregated in the lamina propria of the small intestine and parapancreatic and perienteric lymph nodes, with positive periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (Figure 5); therefore, it was highly suspected to be Whipple’s disease. Immunohistochemistry revealed negative staining for S-100, less than 1% of Ki67 positive cells, and partially positive KP-1 staining. Special staining presented negative acid-fast staining and silver staining. In microbiology, dewaxed duodenum and parapancreatic lymph node tissues were used to perform next-generation genomic sequencing (NGS). However, Tropheryma whipplei was not detected, and Propionibacterium acnes, Moraxella oslogenes, and other normal colonizing bacteria were reported. The patient recovered well after the operation. One week later, the patient gradually resumed eating and the drainage tube was removed.

According to the postoperative pathological results and other clinical evidence, the patient was diagnosed with Whipple's disease.

To exclude involvement of the central nervous system (CNS), lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid tests were recommended for the patient; however, the patient refused these examinations. For antibiotic treatment, the patient received 2 g of ceftriaxone intravenously every day for 2 wk, followed by oral administration of doxycycline 100 mg twice a day combined with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg three times a day, which has been used for 1 mo to date.

At 2 mo postoperatively, the fatigue and decreased exercise capacity of the patient were significantly improved, and hemoglobin levels increased to 114 g/L.

In recent years, great progress has been made in microbiology and antibiotic therapy for Whipple’s disease. However, due to its low incidence, lack of specific clinical manifestations, and limited testing methods, there is still no uniform standard for diagnosing Whipple’s disease. According to several recent representative reviews, the final diagnosis is made if both of the following criteria are met: (1) Positive PAS staining in duodenal tissue or other solid tissue; (2) Positive tests by genetic examination and/or T. whipplei-specific immunohistochemistry in tissues or body fluids. However, some cases cannot meet both criteria simultaneously. If cases have positive PAS staining but negative PCR results in duodenal mucosal tissue, diagnosing Whipple’s disease needs further evidence. For example, Günther et al[5] suggested that typical clinical manifestations can be regarded as strong diagnostic evidence. Dolmans et al[6] believed that positive PAS staining in other independent samples supports the diagnosis of Whipple’s disease. This case presented chronic anemia, macroscopic abnormalities in the duodenum and upper jejunum, and enlarged adjacent lymph nodes, which meets typical manifestations of Whipple’s disease. Histologically, many PAS-positive macrophages aggregated in the intestinal mucosa of the duodenum, upper jejunum, and surrounding lymph nodes. Although T. whipplei was not detected by NGS, no other pathogens that lead to positive PAS staining were found, such as Rhodococcus equi, Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, Corynebacterium, Bacillus cereus, Histoplasma, or fungi. Therefore, using the diagnostic criteria mentioned in the above two reviews, the diagnosis of Whipple’s disease was established in this case. Compared with the typical clinical manifestations of Whipple’s disease, the patient did not exhibit gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, or malnutrition, and lacked extraintestinal manifestations, such as arthralgias, cardiac murmurs, and CNS involvement. In addition, genomic detection also found no microbiological evidence of Tropheryma whipplei. As previous studies reported, in cases with negative microbiological detection but suspicious histology, the possibility of previous Tropheryma whipplei-sensitive antibiotic treatment should be considered. When further asked about the history of antibiotic treatment, the patient added that he suffered upper respiratory tract infections every winter, manifesting as symptoms including fever, cough, and sputum, which were gradually relieved after using azithromycin for 3-5 d. It is noteworthy that macrolide antibiotics possess bactericidal effects on Tropheryma whipplei. Therefore, the intermittent and short-term use of azithromycin was postulated to generate a false-negative result of the microbiological examination. On the other hand, it may also delay the systemic damage of Tropheryma whipplei, and some typical symptoms may have not yet been presented.

Gastroscopy and capsule endoscopy are routine diagnostic methods for Whipple's disease. Under digestive endoscopy, Whipple’s disease mainly displays flat lesions, characterized by a pale yellow shaggy mucosa or whitish-yellow plaques in the small intestine, especially in the duodenum or jejunum[7]. Diffuse edema, erythema, and erosions are common endoscopic features[8,9]. Virtual chromoendoscopy additionally revealed edematous and engorged duodenal villi filled with a white material representing lymph[10]. However, few articles have reported intestinal polyps when performing capsule endoscopy or other examinations. In this case, the capsule endoscopy and intraoperative endoscopy showed whitish-yellow plaque-like changes diffusely distributed from the posterior entrance of the duodenal bulb to approximately 100 cm of the anal side of the jejunum. Based on the endoscopic features of the mucosa mentioned above, multiple polypoid changes were present from the descending duodenum to the anal side of the jejunum, with a length of 60 cm. To the best of our knowledge, whitish-yellow plaques are characteristic changes in Whipple’s disease, whereas multiple polypoid changes have not yet been reported in Whipple’s disease. Histological results showed that the polypoid and whitish-yellow plaques showed the accumulation of many PAS-positive macrophages in the lamina propria. It could be inferred that polypoid lesions were developed by further progression based on whitish-yellow plaque-like lesions. On the other hand, this patient had no endoscopic manifestations of mucosal edema, erythema, or erosions, which may be why no gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea or abdominal pain, were found.

In this case, polypoid changes of various sizes were diffusely distributed in the duodenum and proximal jejunum, which was quite similar to familial adenomatous polyposis. Therefore, small intestinal adenomatosis was initially considered in the local hospital, which stirred a strong desire for the patient and his families to receive surgical treatment. However, the mucosal surface of the polyps was smooth and plaque-like in the macroscopic manifestation, which was significantly different from the opening structure of tubular or gyrus-like ducts on the surface of adenomas. Therefore, the diagnosis of small intestinal adenomatosis should not have been prioritized. Instead, the endoscopic manifestation of this patient was more common in small intestinal lymphangiectasia, which is characterized by hypoalbuminemia, edema, diarrhea, and lymphopenia. According to the etiology, small intestinal lymphangiectasis is divided into primary and secondary types. The former is often caused by congenital lymphoid dysplasia, while the latter is secondary to lymphatic circulation disorders caused by various causes[11]. The macroscopic changes are characterized by small intestinal mucosal edema, thickened villi, white plaques, nodules, and polypoid morphology, which mimic this case[12]. However, this case did not meet the clinical manifestations of intestinal lymphangiectasia and had no sign of hypoalbuminemia or lymphopenia. Moreover, the histological manifestation in this case did not support the diagnosis of intestinal lymphangiectasia. However, several limitations should be considered. First, due to the patient refusing further evaluation of other systems, such as lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid tests for the CNS, the risk of other system involvement is unclear. Follow-up is necessary and valuable to help detect the recurrence of symptoms. Second, we failed to find positive PCR results for Tropheryma whipplei. This case was diagnosed with Whipple’s disease, yet showed multiple polypoid bulges distributed in the duodenal and proximal jejunum. If a biopsy of duodenal polypoid lesions could have been completed by gastroscopy with anesthesia at first, a further pathological investigation would have provided critical preoperative data, which may have changed this case's follow-up diagnosis and prevented treatment with the Whipple procedure.

This article introduces a case of Whipple’s disease with atypical gastrointestinal manifestations and macroscopic changes, namely, small intestinal polypoid bulges. Through reviewing this case, we have new insight into the endoscopic manifestations of Whipple’s disease. We have broadened the understanding of the differential diagnosis of multiple polypoid lesions of the small intestine to prevent misdiagnosis and mistreatment of similar cases. Moreover, this patient's diagnosis and treatment process highlights the importance of obtaining pathological results before surgery.

We would like to thank the patient described in this case report for agreeing to the publication of his case.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Society of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cabezuelo AS, Spain; Glaser C, Germany S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Fenollar F, Puéchal X, Raoult D. Whipple's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Boumaza A, Ben Azzouz E, Arrindell J, Lepidi H, Mezouar S, Desnues B. Whipple's disease and Tropheryma whipplei infections: from bench to bedside. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e280-e291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Puéchal X. Whipple's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:797-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boulos A, Rolain JM, Mallet MN, Raoult D. Molecular evaluation of antibiotic susceptibility of Tropheryma whipplei in axenic medium. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55:178-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Günther U, Moos V, Offenmüller G, Oelkers G, Heise W, Moter A, Loddenkemper C, Schneider T. Gastrointestinal diagnosis of classical Whipple disease: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic features in 191 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dolmans RA, Boel CH, Lacle MM, Kusters JG. Clinical Manifestations, Treatment, and Diagnosis of Tropheryma whipplei Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:529-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marth T, Raoult D. Whipple's disease. Lancet. 2003;361:239-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Roulet J, Hassan MO, Cummings LC. Capsule endoscopy in Whipple's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:A26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kunogi T, Ando K, Fujiya M. Balloon endoscopy and capsule endoscopy are useful in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions in Whipple's disease. Dig Endosc. 2022;34:248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Neumann H, Neufert C, Vieth M, Siebler J, Mönkemüller K, Neurath MF. High-definition endoscopy with i-scan enables diagnosis of characteristic mucosal lesions in Whipple's disease. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E217-E218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann's disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (36)] |

| 12. | Asakura H, Miura S, Morishita T, Aiso S, Tanaka T, Kitahora T, Tsuchiya M, Enomoto Y, Watanabe Y. Endoscopic and histopathological study on primary and secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1981;26:312-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |