Published online Jul 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6130

Peer-review started: March 29, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: April 30, 2021

Accepted: May 20, 2021

Article in press: May 20, 2021

Published online: July 26, 2021

Processing time: 114 Days and 1.1 Hours

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) manifests many neurolo

A 73-year-old man was transferred to our hospital for sepsis due to acute cholangitis. He had already received hemodialysis for two weeks due to septic acute kidney injury. His azotemia was not improved after sepsis resolved and perinuclear-ANCA was positive. Kidney biopsy showed crescentic glomerulonephritis. Alveolar hemorrhage was observed on bronchoscopy. He was initially treated with intravenous methylprednisolone and plasma exchange for one week. And then, two days after adding oral cyclophosphamide, the patient developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures. We diagnosed PRES by Brain mag

The present case shows the possibility of PRES induction due to short-term use of oral cyclophosphamide therapy. Physicians should carefully monitor neurologic symptoms after oral cyclophosphamide administration in elderly patients with underlying diseases like sepsis, renal failure and ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Core Tip: Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a neurological disease that can occur suddenly during the clinical course of various disorders. Since the clinical course of PRES is reversible, it is important to diagnose it quickly and correct the cause. Cyclophosphamide has recently been reported as one of the causes of PRES. This is the first report that PRES occurred at the early onset of oral cyclophosphamide therapy. Physicians should carefully monitor neurologic symptoms after oral cyclophosphamide administration in elderly patients with underlying diseases like sepsis, renal failure, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

- Citation: Kim Y, Kwak J, Jung S, Lee S, Jang HN, Cho HS, Chang SH, Kim HJ. Oral cyclophosphamide-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in a patient with ANCA-associated vasculitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(21): 6130-6137

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i21/6130.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i21.6130

The symptoms of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) include headache, seizure, visual disturbance, and loss of consciousness with varying severity. PRES shows typical features in the posterior parietal-temporal-occipital areas on brain imaging[1]. Risk factors for PRES include immunosuppressive agents, cytotoxic drugs, renal disease, autoimmune disease, hypertensive encephalopathy, organ transplan

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent widely used in the treatment of certain malignancies and autoimmune diseases[3,4]. Intravenous (IV) cyclophosphamide-induced PRES has been reported in several cases where cyclophosphamide was used to treat rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN) including anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis[3,5,6]. However, all these cases occurred at least 3 wk after administration of oral cyclophosphamide[7,8]. Herein, we present a case of PRES appearing after short-term administration of oral cyclophosphamide in a patient with RPGN caused by ANCA-associated vasculitis.

A 73-year-old man was consulted to nephrology for persistent oliguric azotemia during admission to hepatology of our hospital.

He already started hemodialysis via right internal jugular vein long-term dialysis catheter at one month ago due to septic acute kidney injury with uremic symptoms and oliguria. His azotemia and oliguria were not improved after sepsis resolving and he was still receiving hemodialysis for one month.

He had received intravenous antibiotic therapy and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage state for sepsis due to acute cholangitis and common biliary duct cancer for one month.

He denied taking any medications and past medical history except antibiotic therapy.

His blood pressure was 148/80 mmHg and he had both sides of pretibial pitting edema.

His initial blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine (sCr) were 46.8 mg/dL and 5.33 mg/dL. But his sCr was 0.8 mg/dL at one month ago. His total protein, serum albumin and total cholesterol were 5.6 g/dL, 2.2 g/dL and 136 mg/dL, respectively. Urinalysis revealed proteinuria (+1) with a protein/creatinine ratio of 3.6 mg/mg and microscopic hematuria. Serologic tests for viral hepatitis were all negative, and serum immunologic tests were within normal range for C3 and C4 and negative for anti-nuclear antibody (Ab), anti-ds DNA Ab, immunoglobulin G, A, and M levels, cryo

Kidney needle biopsy and bronchoscopy were performed due to clinically suspected RPGN.

Renal pathologic findings were compatible with crescentic glomerulonephritis. Bronchoscopic finding showed diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. The patient’s final diagnosis was ANCA-associated vasculitis with pulmonary-renal syndrome.

We chose plasma exchange with oral cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids therapy for newly diagnosed ANCA-associated vasculitis with severe renal failure[9]. But we delayed cyclophosphamide after plasma exchange finished because he was still receiving antibiotic therapy for acute cholangitis. He was initially treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 30 mg/d and therapeutic plasma exchanges at the same time. After three times of plasma exchange for one week was done, oral cyclophosphamide 100 mg/d was started. The third day after the second dose of oral cyclophosphamide therapy, the patient suddenly developed generalized tonic-clonic seizures with deviation of both eyeballs for 30 s, five times consecutively, and when the seizure attack occurred, blood pressure was 175/76 mmHg. After the seizure, the patient exhibited stuporous mental status.

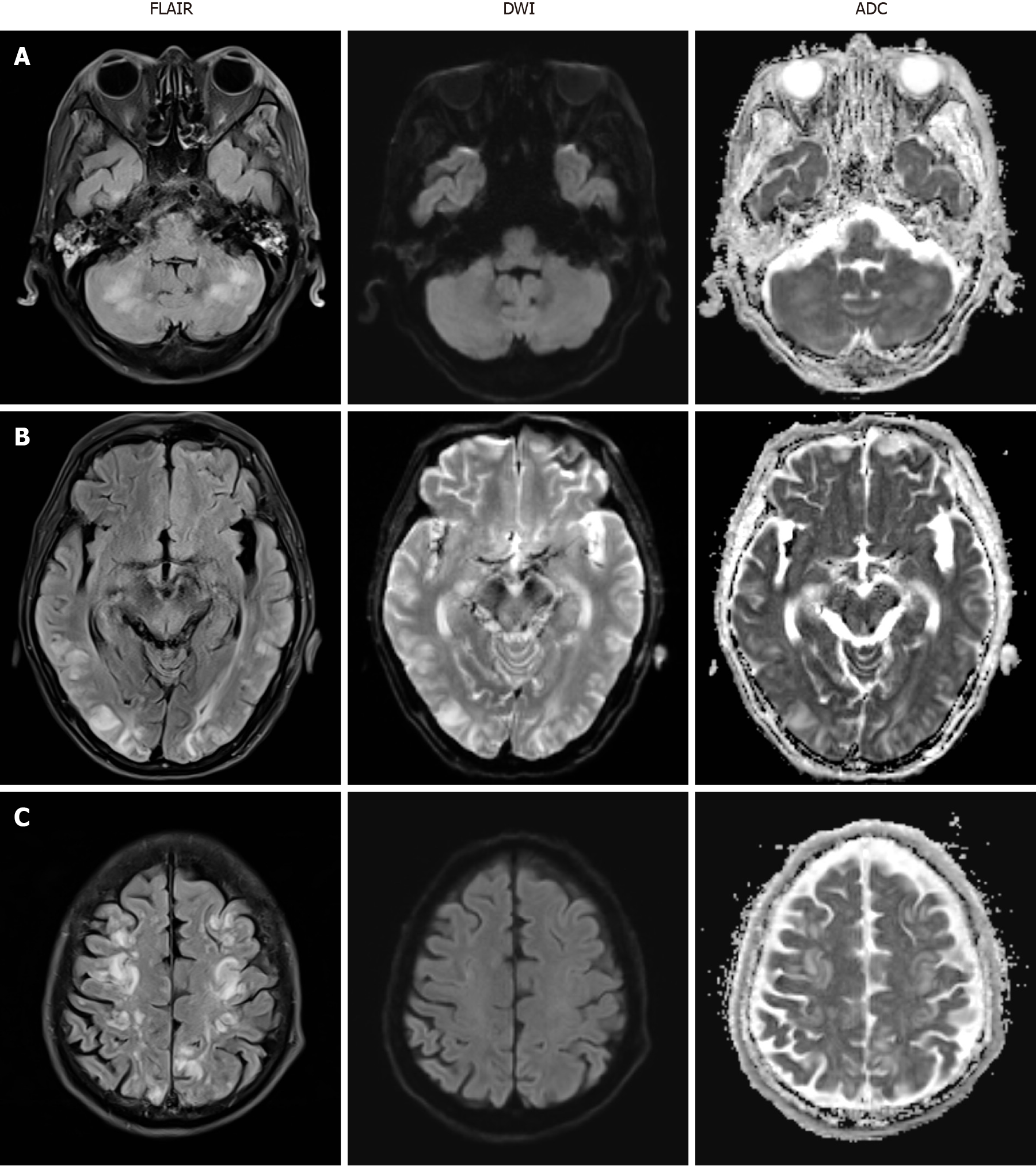

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was immediately performed and revealed multifocal high signal intensity in both frontoparietal lobes, temporal lobes, occipital lobes, cerebellum and pons on T2 fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) but no abnormal change on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) (Figure 1). Electroencephalography showed frequent short bursts of bilateral polymorphic delta to theta slow waves of medium to high amplitude, mixed with short-attenuated periods.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was cyclophosphamide-induced PRES.

We discussed the seizure management of this patient with the neurologist of our hospital. Seizure was controlled by administration of IV fosphenytoin 750 mg. IV methylprednisolone (30 mg/d) was continued but cyclophosphamide was discontinued due to the cause of PRES suspected.

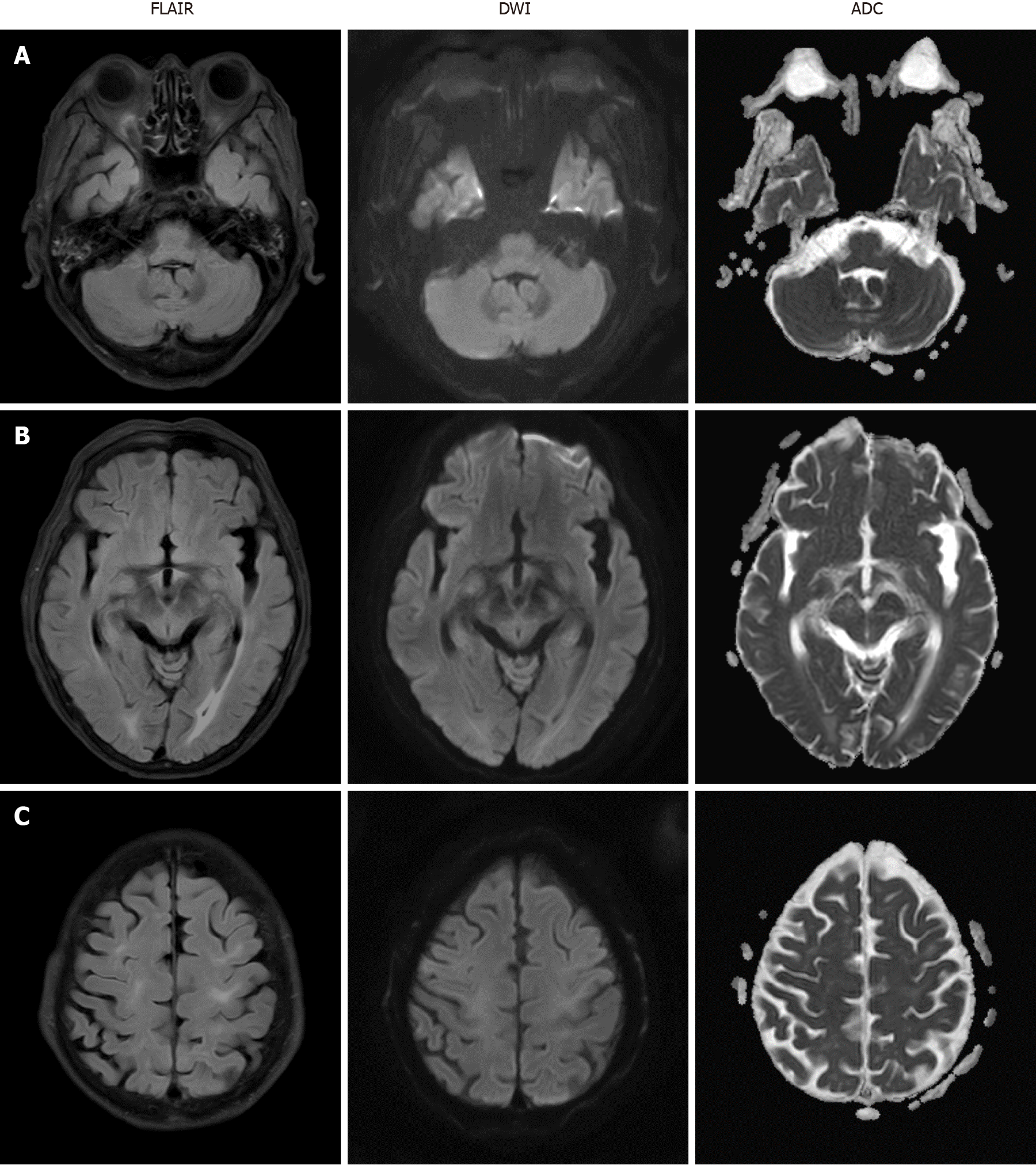

Mental status fully recovered approximately seven days after the seizure attack. Follow-up brain MRI was performed two weeks after PRES onset and the images indicated that the disseminated enhancing lesions on T2 FLAIR had resolved (Figure 2) and the patient had no neurologic symptoms at this time.

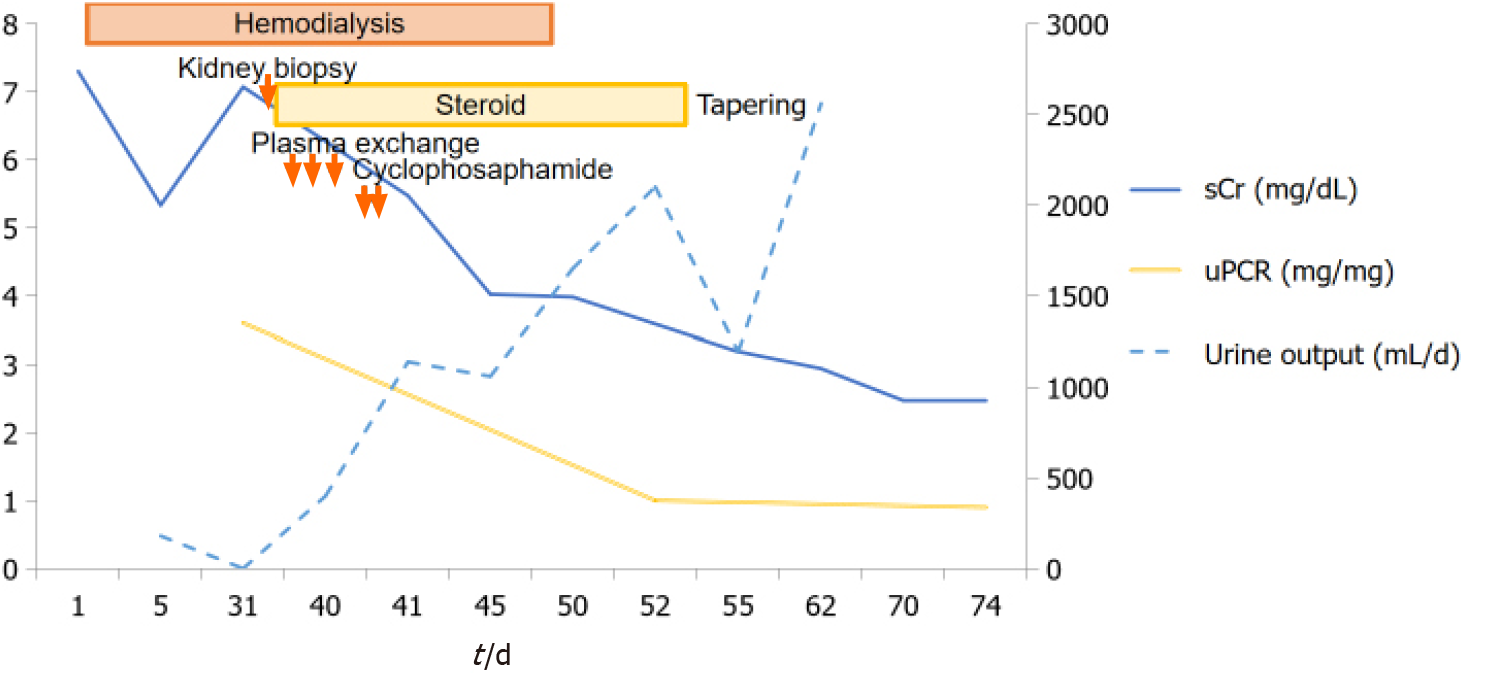

After 10 d of seizure, oliguria was resolved and sCr recovered to 3.98 mg/dL. Hemodialysis was discontinued and the patient was discharged from the hospital with oral prednisolone. His clinical course was shown in Figure 3.

After follow-up for 4 mo at an outpatient clinic, he was treated with a maintenance dose of oral methylprednisolone (10 mg/day) with gradual tapering. His renal function was maintained at stable chronic kidney disease stage G4A2 (sCr, 2.41 mg/dL; eGFR by CKD-EPI, 25 mL/min per 1.73 m2; urine protein/creatinine ratio, 0.3 mg/mg). He has not relapsed any other neurologic symptoms.

PRES is a clinico-radiographic syndrome of varying etiology that was first described in a 1996 case series. The pathophysiology of PRES is a breakdown of cerebral autoregulation due to hypertensive encephalopathy, leading to disruption of the blood-brain barrier with fluid transudation and hemorrhage. Origins of PRES are diverse and often include hypertensive encephalopathy, renal failure, sepsis, vasculitis, autoimmune diseases, immunosuppressive agents and cytotoxic drugs[1,2].

Cyclophosphamide is an immunosuppressive drug widely used for the treatment of malignancy and autoimmune diseases like glomerulonephritis and ANCA-associated vasculitis. It is well described side effects of cyclophosphamide like leukopenia, severe infection, amenorrhea and malignancy[10]. But it has recently been reported that cyclophosphamide is one of the causes of PRES. Especially, cyclophosphamide-induced PRES was reported in eight patients with RPGN (Table 1). Their PRES were more frequently developed in IV infusion than in oral prescription. It took longer to develop PRES with oral cyclophosphamide compared to IV drugs. Furthermore, two patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis and one with lupus nephritis who used IV injection developed PRES in 3 d[5,6,11]. Among two cases of oral cyclophosphamide-induced PRES, Cha et al[7] reported a 36-year-old woman with anti-GBM Ab glomerulonephritis treated with oral methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis and oral cyclophosphamide who suddenly developed PRES after 3 mo of treatment. Ganesh et al[8] reported a 25-year-old female with Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis with crescents. She was treated with IV methylprednisolone and oral cyclophosphamide who developed PRES 26 days after starting cyclophosphamide. But our patient developed PRES 3 days after starting cyclophosphamide. Therefore, this is the first case of early onset of oral cyclophosphamide-induced PRES.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Country | Renal diagnosis | Immunosuppressant | BP (mmHg) | SCr (mg/dL) | Onset of PRES after CP (d) | Recovery time (d) |

| Abenza-Abildua et al[3] | 27 | F | Spain | Anti-GBM disease | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 185/105 | 8.5 | 30 | 2 |

| Lee et al[4] | 45 | F | South Korea | Lupus nephritis | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 190/100 | 2.68 | 16 | 20 |

| Scailteux et al[5] | 75 | M | France | ANCA vasculitis | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 164/91 | 2.40 | 3 | 18 |

| Jabrane et al[11] | 16 | F | Morocco | Lupus nephritis | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 120/70 | 5.8 | 3 | 1 |

| Pan et al[6] | 22 | F | United States | ANCA vasculitis | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 170/110 | 1.47 | 3 | NR |

| Cha et al[7] | 36 | F | South Korea | Anti-GBM disease | Pulse Pd, oral CP | 200/120 | 4.7 | 90 | 28 |

| Zekić et al[16] | 18 | F | Croatia | Lupus nephritis | Pulse Pd, IV CP | 160/100 | Normal | 14 | 45 |

| Ganesh et al[8] | 25 | F | India | H-S purpura | Pulse Pd, oral CP | Normal | Moderate RF | 26 | NR |

| Present | 73 | M | South Korea | ANCA vasculitis | Pulse Pd, oral CP | 175/76 | 5.47 | 3 | 7 |

Several mechanisms are suggested as the cause of PRES in these patients. First is sudden hypertension because high blood pressure was reported in seven of nine PRES cases (Table 1). Hypertensive episodes or blood pressure fluctuations above the upper limit of autoregulation lead to cerebral hyperperfusion and cause vascular leakage and vasogenic edema. The posterior cerebrum areas appear particularly susceptible to blood circulation changes. Second is endothelial dysfunction caused by endogenous or exogenous toxins from cytotoxic substances, eclampsia, sepsis or autoimmune disorders. Immunologic reactions may trigger endothelial activation due to excessive cytokine release followed by vascular leakage of proteins and fluid into the intersti

When this patient was diagnosed with PRES, he had some risk factors such as immunosuppressive therapy, abrupt hypertension at the onset of seizure, azotemia, sepsis, ANCA-associated vasculitis as autoimmune disease and renal failure. However, seizures might not be the result but the cause of high blood pressure in this patient because his blood pressure was well controlled before seizure. His uremic symptoms and azotemia were also stable by regular hemodialysis for one month even though it was not normal. Both sepsis and vasculitis may cause damage to vascular endothelial cells to varying degrees. But his cholangitis was nearly improving state after antibiotic medication for six weeks at the time of seizure attack. And the activity of vasculitis was controlled by steroid pulse therapy and plasma exchange for one week. So, we could rule out the sepsis and vasculitis as the cause of PRES. We suspected the cyclophosphamide as the cause of PRES in this patient even though short-term use of oral cyclophosphamide. Seizure with loss of consciousness spontaneously resolved after cyclophosphamide withdrawal. We suggest that the contributing factors of early onset of oral cyclophosphamide-induced PRES is his severe azotemia, old age and underlying disease of sepsis and ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Our case report indicates that even short-term treatment with oral cyclophosphamide can cause PRES as a side effect of cyclophosphamide. Physicians should carefully monitor neurologic symptoms after oral cyclophosphamide administration in elderly patients with underlying diseases like sepsis, renal failure, and ANCA-associated vasculitis.

The authors thank the patient for his support.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: International Society of Nephrology, No. 52629; American Society of Nephrology, No. 136426.

Specialty type: Urology and Nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhang L S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, Breen J, Pao L, Wang A, Pessin MS, Lamy C, Mas JL, Caplan LR. A reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:494-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2250] [Cited by in RCA: 2147] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fischer M, Schmutzhard E. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. J Neurol. 2017;264:1608-1616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abenza-Abildua MJ, Fuentes B, Diaz D, Royo A, Olea T, Aguilar-Amat MJ, Diez-Tejedor E. Cyclophosphamide-induced reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee CH, Lee YM, Ahn SH, Ryu DW, Song JH, Lee MS. Cyclophosphamide-induced Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in a Patient with Lupus Nephritis. J Rheum Dis. 2013;103. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Scailteux LM, Hudier L, Renaudineau E, Jego P, Drouet T. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome after a First Injection of Cyclophosphamide: A Case Report. J Pharm. 2015;163. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pan D, Sabharwal B, Vallejo F. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Secondary to Cyclophosphamide in the Treatment of Pulmonary Renal Syndrome. Chest. 2017;A367. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cha B, Kim DY, Jang H, Hwang SD, Choi HJ, Kim MJ. Unusual Case of Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in a Patient with Anti-glomerular Basement Membrane Antibody Glomerulonephritis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2017;15:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ganesh K, Nair RR, Kurian G, Mathew A, Sreedharan S, Paul Z. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome in Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3:502-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Geetha D, Jefferson JA. ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: Core Curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75:124-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dan D, Fischer R, Adler S, Förger F, Villiger PM. Cyclophosphamide: As bad as its reputation? Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w14030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jabrane M, Ait Lahcen Z, Fadili W, Laouad I. A case of PRES in an active lupus nephritis patient after treatment of corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:935-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marra AM, Barilaro G, Villella V, Granata M. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and PRES: a case-based review of literature in ANCA-associated vasculitides. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1591-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: clinical and radiological manifestations, pathophysiology, and outstanding questions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:914-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 714] [Article Influence: 71.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jayaweera JL, Withana MR, Dalpatadu CK, Beligaswatta CD, Rajapakse T, Jayasinghe S, Chang T. Cyclophosphamide-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES): a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Grochow LB, Colvin M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1979;4:380-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zekić T, Benić MS, Antulov R, Antončić I, Novak S. The multifactorial origin of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in cyclophosphamide-treated lupus patients. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:2105-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |