Published online Jul 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5637

Peer-review started: February 23, 2021

First decision: March 28, 2021

Revised: March 30, 2021

Accepted: May 20, 2021

Article in press: May 20, 2021

Published online: July 16, 2021

Processing time: 134 Days and 6.3 Hours

Primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignancy, and has only been reported in the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and lymph nodes until now. Extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC in the perinephric space has not been reported. Herein, we report the first case of ACC in the perinephric space and describe its clinical and imaging features, which should be considered when differentiating perinephric space neoplasms.

A 48-year-old man with a 5-year history of hypertension was incidentally found to have an asymptomatic right retroperitoneal mass during a routine health check-up. Laboratory tests were normal. Abdominal computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging showed an oval hypervascular mass with a central scar and enhanced capsule in the right perinephric space. After surgical resection of the neoplasm, the diagnosis was primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC. The patient was alive without recurrence or metastasis during a 15-mo follow-up.

This is the first report of an extra-pancreatic ACC in right perinephric space, which should be considered as a possible diagnosis in perinephric tumors.

Core Tip: Primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignant tumor, with very few reported cases. Extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC arising in the perinephric space has not been reported. The imaging characteristics of our case included an oval shape, relatively homogenous density or signal, a hypervascular pattern and rapid washout with enhancement, and an enhanced capsule. This report of diagnosis and treatment of this rare tumor. will be helpful for clinicians, radiologists and pathologists to differentiate this unusual tumor from other plausible retroperitoneal neoplasms. The recommended treatment for this tumor is complete surgical resection.

- Citation: Wei YY, Li Y, Shi YJ, Li XT, Sun YS. Primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma in the right perinephric space: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(20): 5637-5646

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i20/5637.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i20.5637

Acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) is a rare malignant pancreatic exocrine tumor arising from pancreatic acinar cells, and accounting for less than 1% of all primary pancreatic tumors[1,2]. The incidence of extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC is extremely rare, and few cases have been reported. These tumors can arise in extra-pancreatic tissue such as the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and lymph nodes[3-21], and their radiological findings have not been well described. To the best of our knowledge, extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC arising in the perinephric space has not been reported. Herein, we report a case of primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC in the right perinephric space and discuss the imaging findings on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

A 48-year-old asymptomatic man with a history of hypertension was incidentally found to have a right retroperitoneal tumor during a routine health check-up.

The patient had been suffering from hypertension (up to 180/100 mmHg) for 5 years and was regularly taking an antihypertensive drug (telmisartan) to maintain the blood pressure at 155/90 mmHg.

Apart from hypertension, the patient had no relevant previous illnesses.

No aberrant family history was reported.

The patient was normal and healthy, with no suspicious finding on physical examination.

Laboratory tests were normal, including carbohydrate antigen 72-4 (CA72-4), alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9, CA12-5, and neuron-specific enolase.

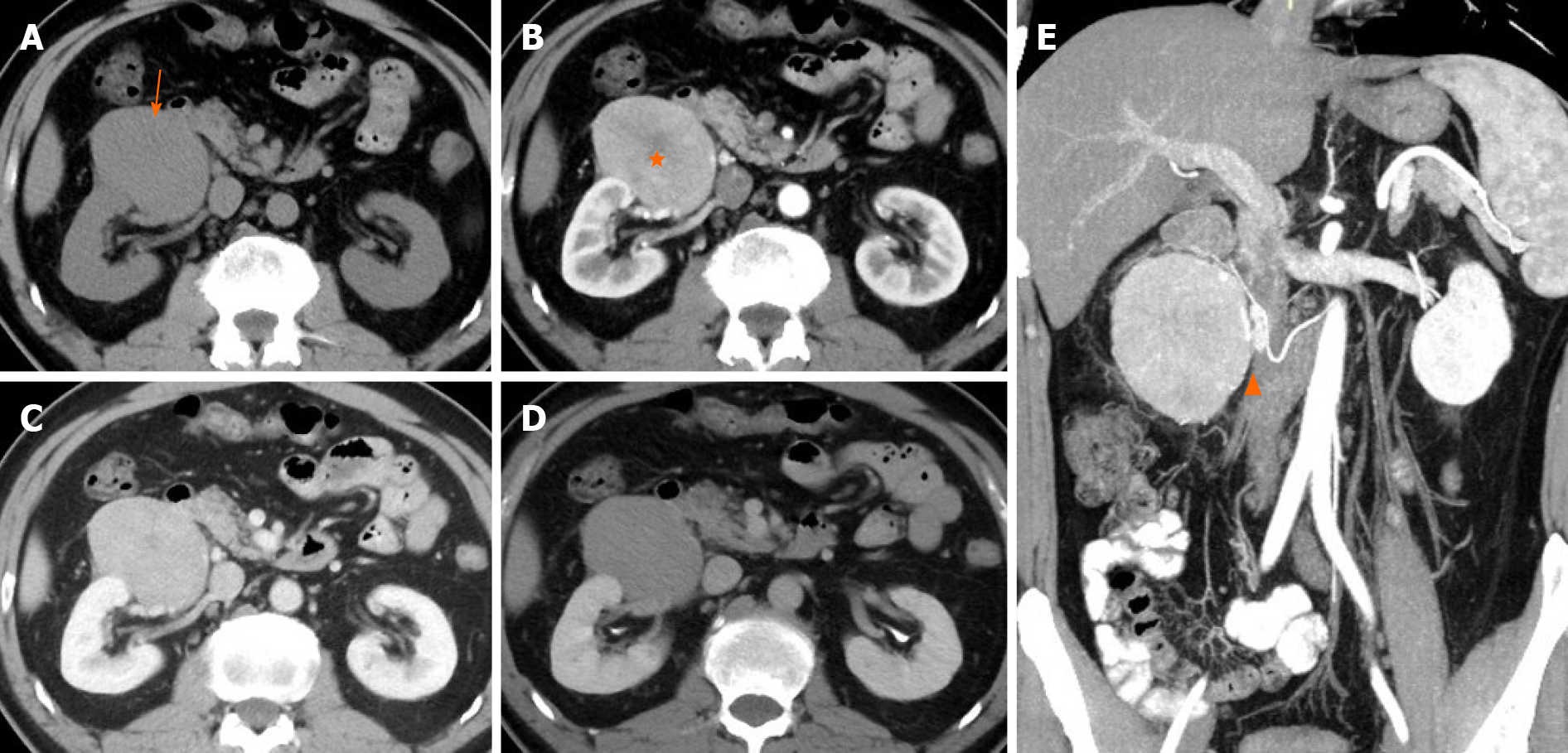

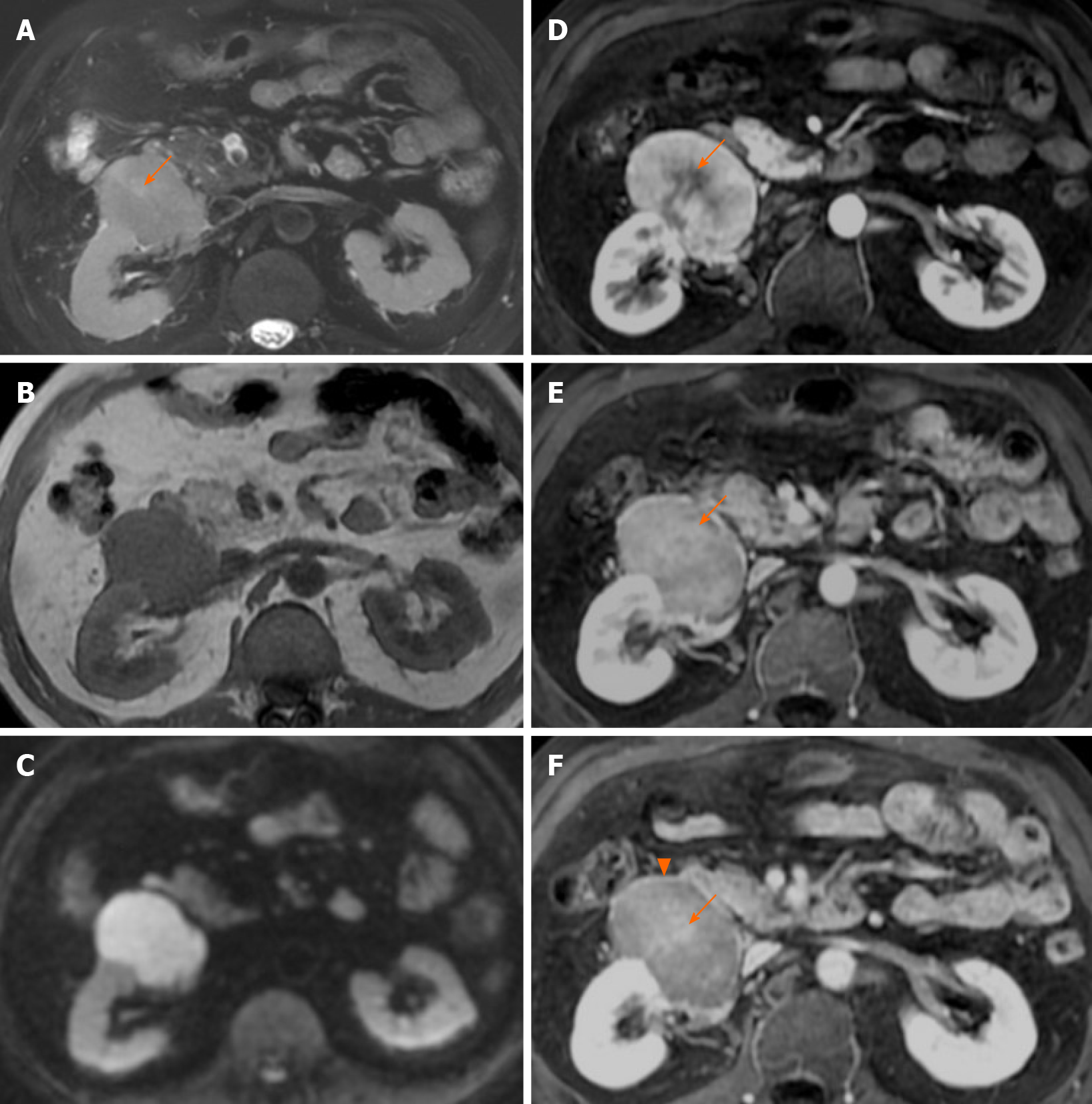

CT of the abdomen and pelvis was performed with a 64-row helical scanner (Discover CT750 HD, General Electrical Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, United States) before and after the injection of nonionic contrast medium (Iohexol; Omnipaque 300, GE healthcare) via the median cubital vein. CT showed an oval 8.0 cm × 7.0 cm × 5.0 cm mass with homogeneous isodensity and a clear margin in the right perinephric space. The tumor showed intense heterogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase and rapid homogeneous washout enhancement in the portal vein and delayed phases (Figure 1A-D). Although the mass was close to the right kidney, no remarkable renal invasion was seen. The mass compressed the duodenum. On multiplanar reconstruction, the blood supply of the tumor was derived from the right testicular artery (Figure 1E). Examination of the abdomen was performed in the supine position with a 1.5T MRI scanner (Brivo MR355; GE healthcare, Waukesha, WI, United States) using a phased-array body coil. A respiration-triggered fast spin echo T2-weighted images (TR/TE, 6667/101) and spin echo T1-weighted images (TR/TE, 180/4.3) showed a right perinephric mass with a heterogeneous signal (low signal on T1WI, slightly high signal on T2WI, Figure 2A and B) and diffusion restriction with high signal on diffusion-weighted imaging (Figure 2C). On dynamic gadolinium-enhanced phases, fat-suppressed spin echo T1-weighted images (TR/TE, 3.7/1.7) showed the same contrast pattern as on the CT scan, but revealed a more sensitive, complete capsule (Figure 2D-F). Owing to high soft tissue contrast on MRI, another characteristic was the presence of a hyperintense central scar on T2-weighted images (Figure 2A), which manifested as late enhancement in the portal vein and delayed phases (Figure 2E and F) that was more sensitive on MRI.

The preoperative differential diagnosis was suspected paraganglioma, solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) or renal oncocytoma. There was no definite clinical or radiological abnormality in the pancreas body, head, or neck. Consistent with the histological features and immunohistochemical staining, the final diagnosis was considered as primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC of perinephric space.

The patient underwent a complete surgical resection. During the operation, a tumor was found in the right perirenal space. It had tortuous and dilated reproductive vessels on the medial side, and was adjacent to the right renal capsule on the rear side. The tumor was completely removed without any complications.

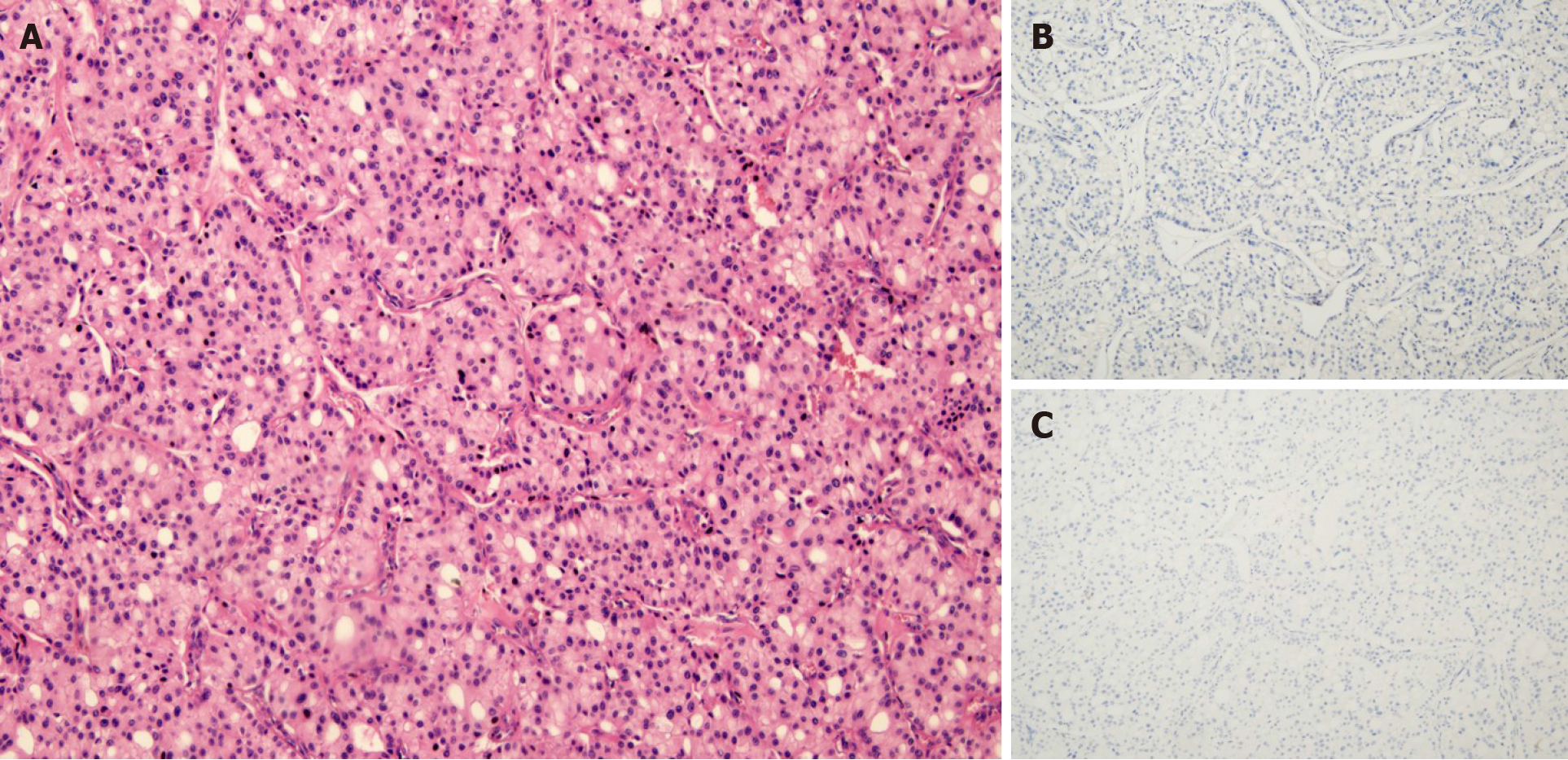

The gross tumor appeared as a near-spherical mass with a distinct border, medium-size, gray cross sections, and an intact capsule. Histomorphologically, the growth pattern of the proliferative tumor cells had an acinar appearance. Immunohistochemical staining revealed tumor cells that were negative for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56, which suggested the absence of neuroendocrine differentiation (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical staining also found Ki-67-positive (10%+) tumor cells; other indicators were negative.

The patient had no complications and was discharged from our hospital 7 d after the resection. The patient did not receive any adjuvant therapy and had no recurrence or metastasis at the 15 mo follow-up evaluation.

Primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC is rare. The first case of primary extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC was traced back to 1746 and mentioned by Hamburger in a 1932 article by Bookman[10]. Since then, 21 cases of extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC have been reported in PubMed. The causes of extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC remain unclear. There are two hypotheses about the possible mechanism of extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC. The first is that malignant transformation occurs in tissue metaplasia or in ectopic pancreatic tissue, which is common in the gastrointestinal tract[5,6,13,14,17,21]. This hypothesis is supported by three cases with definite evidence of residual metaplasia or ectopic pancreatic tissue in the resected specimens[6,14,21]. The investigators speculated that the tumor might have completely destroyed the original structure, without any residue of benign ectopic pancreatic tissue remaining[14]. Another hypothesis that multipotential progenitor cells acquire acinar pancreatic features is supported by Terris et al[16] and Agaimy et al[22], who reported three cases of extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC in peripancreatic lymph nodes, and in lymph nodes along the biliary tract, hepatic hilum, colon, and retroperitoneum[16].

The characteristic microscopic architecture of ACC includes acinar units, with neoplastic cells arranged in small acinar units, and in solid nests of neoplastic cells lacking luminal formations[18]. In our patient, the tumor had the characteristic acinar growth pattern, neuroendocrine marker-negativity and acinar structures, and tumor cells were arranged as pancreatic acini (Figure 3). Lesions were not detected either by imaging (CT, MRI, endoscopic ultrasonography) or during the surgical exploration. There was no confirmation of a macroscopic intrapancreatic tumor. We also considered the differentiation of salivary gland ACC, which most often occurs in the parotid gland, and its histological characteristics show serous acinar differentiation[19] with frequent expression of cytokeratin and partial expression of S-100[20]. As the head and neck workup did not identify a primary salivary gland tumor, and the histological and immunohistochemical studies did not support a head or neck origin, our case was not considered as arising from the head or neck. As a pancreatic or head and neck origin could be excluded, and the presence of associated glandular components was revealed, we speculated that our ACC case originated from retroperitoneal multipotential progenitor cells that acquired acinar pancreatic features. A diagnosis of pancreatic-type ACC of the right perinephric space was made.

In contrast to extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC, there are numerous reports on CT and MRI features of pancreatic ACC (PACC). Although presenting a wide range of features, the images of PACC can be summarized as a relatively large oval or round solid mass (average 7.1 cm), exophytic growth, a clear margin with an enhanced capsule, hypovascularity compared with the pancreatic parenchyma, lack of or relatively mild pancreatic ductal dilation or vascular encasement compared with pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma, internal necrosis, cystic changes, always accompanied by invasion of adjacent organs, and extensive metastasis[23-30]. Tumor encapsulation is a specific finding for the diagnosis of PACC, however it may be misleading because of similar characteristics of other tumors[31,32]. Several case reports of extra-pancreatic ACCs have been published by surgeons and pathologists. Therefore, the main focus of those reports was not the imaging features. Consequently, only few cases with radiological features were reported, briefly describing the CT examination (Tables 1 and 2), and no reports of MRI. Those cases merely revealed marked homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancements (Tables 1 and 2) without any detailed information. Here we present detailed images of a case with extra-pancreatic ACC in the perirenal space and summarize the CT and MRI characteristics as an encapsulated solid mass, a well-defined contour, relatively homogenous density or signal, hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and withdrawal enhancement in the portal vein and delayed phases, and an enhanced capsule. However, those imaging manifestations can also be found in other hypervascular peritoneal neoplasms, such as paraganglioma, SFT, or renal oncocytoma. First, considering paraganglioma, the patient's history of hypertension made the differential diagnosis difficult. Retroperitoneal extra-adrenal paragangliomas usually occur in the Zuckerkandl body and the para-aortic sympathetic nervous chain at the renal hilum level[30]. They can synthesize and secrete large amounts of catecholamines, which can cause a clinical syndrome that includes blood pressure elevation. Benign small-volume tumors with a uniform density often appear. Larger oval or lobulated soft tissue masses with clear boundaries are usually accompanied by necrosis and hemorrhage. Tortuous vessels can be seen around or within these hypervascular tumor components[31]. Malignant paragangliomas are characterized by invasiveness and dissemination. However, the presence of homogeneous density without any necrosis or hemorrhage, and relatively well-proportioned enhancement in our case made that diagnosis unlikely. Second, retroperitoneal SFTs typically have a well-circumscribed margin, intense but heterogeneous enhancement on the arterial phase, and persistent enhancement on the delayed phase[32]. Retroperitoneal SFTs can present with hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic degeneration. However, the enhanced pattern of our case (fast-in and fast-out) was not consistent with a typical retroperitoneal SFT (persistent enhancement). Finally, renal oncocytomas can show hypointensity in T2WI, have an abundant blood supply, central scar, delayed enhancement, and a capsule, which should be considered. However, renal oncocytoma primarily originates from the renal collecting duct, protruding in the renal contour. The boundary between the tumor and the kidney in our case was smooth without any evidence of a “break sign”, which made the diagnosis of renal oncocytoma unlikely. Hypothetically, the stellate central scar in our case might have been a reaction of fibrosis, blood vessel, or infiltrated inflammatory regions resembling renal oncocytoma or focal nodular hyperplasia[33,34]. Consequently, the findings in our case might help to discriminate between extra-pancreatic pancreatic-type ACC and other hypervascular perinephric neoplasms.

| Ref. | Age/sex | Tumor location | Tumor size in cm | Metastasis, yes/no | Preoperative diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

| Bookman[10], 1932 | 28/F | Duodenum | NM | No | Begin: Such as polyp | Partial resection | NM |

| Makhlouf et al[14], 1999 | 71/M | Jejunum | 3.5 | No | NM | Partial resection | 1 yr alive, liver metastasis at 1 yr |

| Sun and Wasserman[5], 2004 | 86/M | Stomach | 5 | No | PDA | Partial gastrectomy | NM |

| Mizuno et al[6], 2007 | 73/M | Pylorus | 7 | LN | GIST/ML | PD | 11 mo alive, liver metastasis at 7 mo |

| Kawakami et al[11], 2007 | 65/F | AoV | 1.2 | No | Carcinoma of AoV | PD | 19 mo alive, NR |

| Hervieu et al[12], 2008 | 35/F | Liver | 4 | No | HCC | Hepatectomy | 6 yr alive, NR |

| Chiaravalli et al[13], 2009 | 65/F | Colon | 4 | LN | NM | Colonic segment resection | 24 mo died with diffuse bone metastasis at 18 mo |

| Ambrosini et al[7], 2009 | 52/M | Stomach | 4 | No | PDA and chronic gastritis | Subtotal gastrectomy | NM |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | Case 1: 68/F | Liver | 7 | No | HCC | Hepatectomy | 38 mo alive, NR |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | Case 2: 49/F | Liver | NM | NM | NM | Hepatectomy | 28 mo alive, NR |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | Case 3: 71/M | Liver | NM | No | HCC | Hepatectomy | 3 mo died |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | Case 4: 72/M | Liver | NM | NM | CCC | Hepatectomy | 20 mo alive, recurrence at 18 mo |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | Case 1: 52/M | Peripancreatic lymph nodes | 3 | LN | NM | Left pancreatectomy | 10 mo alive with liver metastasis |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | Case 2: 59/F | Lymph nodes along the biliary tract and liver hilum | NM | LN | NM | Hepatectomy | 6 mo alive |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | Case3: 73/M | Colonic tumor and retroperitoneal lymph nodes | 4 | Liver | NM | Right hemicolectomy | 6 mo alive with recurrence |

| Coyne et al[8], 2012 | 77/F | Stomach | 4.5 | No | PDA | Partial gastrectomy | NM |

| Hamidian Jahromi et al[3], 2013 | 58/M | Duodenum | 2.7 | No | NM | Duodenal resection | 18 mo alive, NR |

| Yonenaga et al[4], 2016 | Case 1: 67/M | Gastric body | 8.5 | LN | NM | Distal gastrectomy | 21 mo alive, NR |

| Yonenaga et al[4], 2016 | Case 2: 63/M | Antrum of the stomach | 6.5 | Liver | PDA | Chemotherapy | 5 mo died of sepsis |

| Kim et al[9], 2017 | 54/M | Gastric cardia | 2.7 | No | GIST/ML | Laparoscopic wedge resection | 33 mo alive, NR |

| Takagi et al[15], 2017 | 78/F | Jejunum | 8.5 | No | PDA | Partial resection and Chemotherapy | 10 mo alive, NR |

| Our case, 2019 | 48/M | Right perinephric space | 8 | No | Paraganglioma/ renal oncocytoma | Tumor resection | 15 mo alive, NR |

| Ref. | Tumor shape | Tumor contour, well-/ill-defined | Tumor CT image, present/absent | Ulceration, yes/no | Necrosis, yes/no | Enhancement patterns | Capsule, present/absent | Adjacent organ | Metastasis |

| Bookman[10], 1932 | NM | Well-defined | No | NM | NM | No | NM | NM | No |

| Makhlouf et al[14], 1999 | NM | NM | Absent | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Sun and Wasserman[5], 2004 | NM | NM | Absent | Yes | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Mizuno et al[6], 2007 | NM | NM | Present | NM | NM | Marked/heterogenous | NM | NM | LN |

| Kawakami et al[11], 2007 | Nodular | NM | Present | NM | NM | Marked/heterogenous | NM | NM | No |

| Hervieu et al[12], 2008 | NM | Well-defined | Absent | NM | NM | Marked | NM | NM | No |

| Chiaravalli et al[13], 2009 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | LN |

| Ambrosini et al[7], 2009 | NM | NM | Absent | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | NM | Well-defined | Absent | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | Irregular | NM | Absent | NM | Yes | Marked/heterogenous | NM | NM | NM |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | NM | NM | Absent | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Agaimy et al[22], 2011 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | NM | NM | Absent | NM | NM | NM | NM | No | LN |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | NM | NM | Absent | NM | NM | NM | NM | Bile duct | LN |

| Terris et al[16], 2011 | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No | Liver |

| Coyne et al[8], 2012 | Lobulated | Well-defined | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No |

| Hamidian Jahromi et al[3], 2013 | Pedunculated | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | No | No |

| Yonenaga et al[4], 2016 | Lobulated | Well-defined | NM | NM | No | NM | NM | NM | LN |

| Yonenaga et al[4], 2016 | Borrmann type-2 lesion | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | Liver |

| Kim et al[9], 2017 | Polypoid | Well-defined | Present | NM | NM | Marked/homogenous | NM | No | No |

| Takagi et al[15], 2017 | NM | NM | Present | NM | NM | Marked/heterogenous | NM | First jejunal vein | No |

| Our case, 2019 | Oval | Well-defined | Present | No | No | Marked/heterogenous | Present | No | No |

The findings of a retroperitoneal mass with a relatively homogenous density or signal, fast-in and fast-out enhanced patterns, and an enhanced capsule made extra-pancreatic ACC as the most likely diagnosis.

We thank Dr. Dong K, Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research (Ministry of Education), Department of Pathology, Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute, for providing pathological figures of our case.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oura S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ordóñez NG. Pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:144-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Holen KD, Klimstra DS, Hummer A, Gonen M, Conlon K, Brennan M, Saltz LB. Clinical characteristics and outcomes from an institutional series of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas and related tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4673-4678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hamidian Jahromi A, Shokouh-Amiri H, Wellman G, Hobley J, Veluvolu A, Zibari GB. Acinar cell carcinoma presenting as a duodenal mass: review of the literature and a case report. J La State Med Soc. 2013;165:20-23, 25. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Yonenaga Y, Kurosawa M, Mise M, Yamagishi M, Higashide S. Pancreatic-type Acinar Cell Carcinoma of the Stomach Included in Multiple Primary Carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:2855-2864. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sun Y, Wasserman PG. Acinar cell carcinoma arising in the stomach: a case report with literature review. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:263-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mizuno Y, Sumi Y, Nachi S, Ito Y, Marui T, Saji S, Matsutomo H. Acinar cell carcinoma arising from an ectopic pancreas. Surg Today. 2007;37:704-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ambrosini-Spaltro A, Potì O, De Palma M, Filotico M. Pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the stomach beneath a focus of pancreatic metaplasia of the gastric mucosa. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:746-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Coyne JD. Pure pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the stomach: a case report. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:71-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim KM, Kim CY, Hong SM, Jang KY. A primary pure pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the stomach: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2017;12:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bookman MR. Carcinoma in the Duodenum: Originating from Aberrant Pancreatic Cells. Ann Surg. 1932;95:464-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Onodera M, Hirano S, Kondo S, Nakanishi Y, Itoh T, Asaka M. Primary acinar cell carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:694-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hervieu V, Lombard-Bohas C, Dumortier J, Boillot O, Scoazec JY. Primary acinar cell carcinoma of the liver. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chiaravalli AM, Finzi G, Bertolini V, La Rosa S, Capella C. Colonic carcinoma with a pancreatic acinar cell differentiation. A case report. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:527-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Makhlouf HR, Almeida JL, Sobin LH. Carcinoma in jejunal pancreatic heterotopia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:707-711. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Takagi K, Yagi T, Tanaka T, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, Nobuoka D, Kuise T, Fujiwara T. Primary pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the jejunum with tumor thrombus extending into the mesenteric venous system: a case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2017;17:75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Terris B, Genevay M, Rouquette A, Audebourg A, Mentha G, Dousset B, Rubbia-Brandt L. Acinar cell carcinoma: a possible diagnosis in patients without intrapancreatic tumour. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:971-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fukunaga M. Gastric carcinoma resembling pancreatic mixed acinar-endocrine carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:569-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2554] [Cited by in RCA: 2390] [Article Influence: 478.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 19. | Batsakis JG, Luna MA, el-Naggar AK. Histopathologic grading of salivary gland neoplasms: II. Acinic cell carcinomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:929-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Takahashi H, Fujita S, Okabe H, Tsuda N, Tezuka F. Distribution of tissue markers in acinic cell carcinomas of salivary gland. Pathol Res Pract. 1992;188:692-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moncur JT, Lacy BE, Longnecker DS. Mixed acinar-endocrine carcinoma arising in the ampulla of Vater. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:449-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Agaimy A, Kaiser A, Becker K, Bräsen JH, Wünsch PH, Adsay NV, Klöppel G. Pancreatic-type acinar cell carcinoma of the liver: a clinicopathologic study of four patients. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1620-1626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Baek KA, Kim SS, Lee HN. Typical CT and MRI Features of Pancreatic Acinar Cell Carcinoma: Main teaching point: Typical imaging features of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma are relatively large, with a well-defined margin, exophytic growth, and heterogeneous enhancement. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2019;103:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jornet D, Soyer P, Terris B, Hoeffel C, Oudjit A, Legmann P, Gaujoux S, Barret M, Dohan A. MR imaging features of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2019;100:427-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Barat M, Dohan A, Gaujoux S, Hoeffel C, Jornet D, Oudjit A, Coriat R, Barret M, Terris B, Soyer P. Computed tomography features of acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2020;101:565-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hu S, Hu S, Wang M, Wu Z, Miao F. Clinical and CT imaging features of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Radiol Med. 2013;118:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shah S, Mortele KJ. Uncommon solid pancreatic neoplasms: ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging features. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:357-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Matsumoto S, Sata N, Koizumi M, Lefor A, Yasuda Y. Imaging and pathological characteristics of small acinar cell carcinomas of the pancreas: A report of 3 cases. Pancreatology. 2013;13:320-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Guerrache Y, Soyer P, Dohan A, Faraoun SA, Laurent V, Tasu JP, Aubé C, Cazejust J, Boudiaf M, Hoeffel C. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: MR imaging findings in 21 patients. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, Kim KA, Lee NJ. Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:492-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Baez JC, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski K, O'Regan K, Zukotynski K, Kulke M, Ramaiya NH. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: imaging characteristics. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:153-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Keraliya AR, Tirumani SH, Shinagare AB, Zaheer A, Ramaiya NH. Solitary Fibrous Tumors: 2016 Imaging Update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54:565-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pedrosa I, Sun MR, Spencer M, Genega EM, Olumi AF, Dewolf WC, Rofsky NM. MR imaging of renal masses: correlation with findings at surgery and pathologic analysis. Radiographics. 2008;28:985-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hussain SM, Terkivatan T, Zondervan PE, Lanjouw E, de Rave S, Ijzermans JN, de Man RA. Focal nodular hyperplasia: findings at state-of-the-art MR imaging, US, CT, and pathologic analysis. Radiographics. 2004;24:3-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |