Published online Jun 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3838

Peer-review started: August 5, 2020

First decision: October 18, 2020

Revised: November 12, 2020

Accepted: March 18, 2021

Article in press: March 18, 2021

Published online: June 6, 2021

Processing time: 282 Days and 7 Hours

The pathological diagnosis and follow-up analysis of gastric mucosal biopsy have been paid much attention, and some scholars have proposed the pathological diagnosis of 12 kinds of lesions and accompanying pathological diagnosis, which is of great significance for the treatment of precision gastric diseases, the improvement of the early diagnosis rate of gastric cancer, and the reduction of missed diagnosis rate and misdiagnosis rate.

To perform a histopathological classification and follow-up analysis of chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG).

A total of 2248 CAG tissue samples were collected, and data of their clinical characteristics were also gathered. Based on these samples, the expression levels of Mucin 1 (MUC1), MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in CAG tissue were tested by immunohistochemical assay. Moreover, we followed these patients for up to four years. The difference between different stages of gastroscopic biopsy was observed.

Through observation, it is believed that CAG should be divided into four types, simple type, hyperplasia type, intestinal metaplasia (IM) type, and intraepithelial neoplasia (IEN) type. Simple CAG accounted for 9.1% (205/2248), which was more common in elderly people over 60 years old. The main change was that the lamina propria glands were reduced in size and number. Hyperplastic CAG accounted for 29.1% (654/2248), mostly occurring between 40 and 60 years old. The main change was that the lamina propria glands were atrophy accompanied by glandular hyperplasia and slight expansion of the glands. IM CAG accounted for 50.4% (1132/2248), most of which increased with age, and were more common in those over 50 years. The atrophy of the lamina propria glands was accompanied by significant IM, and the mucus containing sialic acid or sulfate was distinguished according to the nature of the mucus. The IEN type CAG accounted for 11.4% (257/2248), which developed from the previous types, with severe gland atrophy and reduced mucus secretion, and is an important precancerous lesion.

The histological typing of CAG is convenient to understand the property of lesion, determine the follow-up time, and guide the clinical treatment.

Core Tip: The pathological diagnosis and follow-up analysis of gastric mucosal biopsy have been paid much attention, and we aimed to perform a histopathological classification and follow-up analysis of chronic atrophic gastritis. The current research results are useful for clinicians to understand the nature and development of the disease, and are important for precision treatment and tracking of malignant transformation.

- Citation: Wang YK, Shen L, Yun T, Yang BF, Zhu CY, Wang SN. Histopathological classification and follow-up analysis of chronic atrophic gastritis. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(16): 3838-3847

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i16/3838.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i16.3838

The pathological diagnosis and follow-up analysis of gastric mucosal biopsy have been paid much attention, and some scholars[1-3] have proposed the pathological diagnosis of 12 kinds of lesions and accompanying pathological diagnosis, which is of great significance for the treatment of precision gastric diseases, the improvement of the early diagnosis rate of gastric cancer, and the reduction of missed diagnosis rate and misdiagnosis rate. Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a common lesion in gastric biopsy and it is mostly divided into mild, moderate, and severe forms in clinical pathologic examination. The definition for mild form is that the decreased proportion of intrinsic glands is less than 1/3 of the original glands. Moderate form means the decrease between 1/3 and 2/3. Severe form means that the proportion of intrinsic glands is over 2/3[4-6]. However, propria gland atrophy in severe form does not show obvious atypical glands, indicating that gland atrophy is not synchronized with intestinal metaplasia (IM). That means the mild, moderate, and severe classifications of CAG cannot reflect the histomorphological characteristics, which is not conducive to the precise treatment by clinical physicians. In our study, we analyzed the clinical manifestations and biopsy sites of 2248 CAG cases from four hospitals, and then divided them into four type, simple type, hyperplasia type, IM type, and intraepithelial neoplasia (IEN) type. In addition, we discussed the histological diagnostic criteria for CAG in order to target the follow-up time, accurate treatment time, improve the detection rate of early gastric cancer, and reduce the incidence of gastric cancer.

Clinical data of a total of 2248 cases that were diagnosed as CAG by gastroscopic biopsy at the pathology departments of Shenzhen Hospital, Southern Medical University, Xinxiang Central Hospital, Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, and Xuchang Central Hospital from February 2014 to July 2018 were collected.

All specimens were fixed in fresh 10% neutral buffered formalin solution and dehydrated routinely. The tissues were then embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm. The tissue structure and cell morphology were observed by hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. The neutral mucus, acidic mucus, and saliva acid mucus were identified by Alcian blue/Periodic acid-Schiff (pH 2.5) staining. We also performed EnVision immunohistochemical staining. The primary antibodies against Mucin 1 (MUC1), MUC2 MUC5AC, and MUC6 were used, which differentiated gastric and intestinal mucin. The working solution was purchased from Fuzhou Maixin Biotechnology Development Co., Ltd (Fuzhou, China). All staining steps were performed strictly in accordance with the kit instructions.

All lesions were divided into four groups, simple type, hyperplasia type, IM type, and IEN type, according to the degree of glandular atrophy, hyperplasia, dilation, metaplasia, and heterogeneity, the quality and quantity of mucus, and the amount of inflammatory cell infiltration. Among them, intestinal epithelial metaplasia can also be divided into small IM and large IM. Small IM had the similar structure with the mucosa absorption cells, both of which had brush border and did not secret mucus. They had goblet cells and brush border that contained acidic mucoprotein. Small IM had overexpressed intestinal MUC2 protein and negatively expressed gastric phenotypes (MUC1, MUC5AC, and MUC6). Colonic epithelial metaplasia had a brush border of metaplastic cells which was lack of development, disordered arrangement of goblet cells, irregular shape (intestinal and immature intermediate mucus cells), and acidic saliva mucus and sulfuric acid mucus. Usually, the metaplastic cells were extensive, and the intestinal cells disappeared and were replaced by columnar cells containing abundant mucus droplets in the cytoplasm. The colonic IM had overexpressed gastric mucin MUC1, MUC5Ac, and MUC6. The atrophic degree was divided into three forms, mild, moderate, and severe. The definition for mild form was that the decreased proportion of intrinsic glands was less than 1/3 of the original glands. Moderate form meant the decrease between 1/3 and 2/3. Severe form meant that the proportion of intrinsic glands was over 2/3[4-6]. The degree of dysplasia was divided into low-grade CAG and high-grade CAG. The degree of glandular expansion was divided into simple expansion and atypia expansion.

A total of 2248 CAG patients were followed for 1 mo to 3 mo, 4 mo to 6 mo, and 7 mo to 12 mo, and reviewed every 6 mo or 12 mo. During the first 1-4 years, the biopsy gastric mucosa was examined for a maximum of 9 times, with a minimum of 2 times. Patients who underwent the examination 4-6 times accounted for 47.2%.

There were 1251 male cases and 997 female cases, which were divided into five groups by age, namely, less than 40 years old, 41-50 years old, 51-60 years old, 61-70 years old, and over 71 years old. Various types of CAG and the age of patients are shown in Table 1. The lesion sites contained the angular incisura, pylorus, gastric body, cardia, and fundus.

| Type | Cases | < 40 | 41-50 | 51-60 | 61-70 | > 70 |

| Simple | 205 | 4 (2.0) | 20 (9.8) | 53 (25.9) | 94 (45.9) | 34 (16.6) |

| Hyperplasia | 654 | 37 (5.7) | 251 (38.4) | 213 (32.6) | 97 (14.8) | 56 (8.6) |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 1132 | 85 (7.5) | 447 (39.5) | 414 (36.6) | 95 (8.4) | 91 (8.0) |

| Intraepithelial neoplasia | 257 | 9 (3.5) | 34 (13.2) | 69 (26.8) | 87 (33.9) | 58 (22.6) |

For 2248 patients, if the same patient had biopsies at several locations at the same time, they would be recorded by location, so the total amount of biopsy was 3384, of which the gastric angle accounted for 19.4% (637/3284), pylorus for 65.1% (2137/3284), gastric body for 7.4% (244/3284), cardia for 5.6% (185/3284), and fundus for 2.5% (81/3284).

The definition for mild form was that the decreased proportion of intrinsic glands was less than 1/3 of the original glands. Moderate form meant the decrease between 1/3 and 2/3. Severe form meant that the proportion of intrinsic glands was over 2/3. The degree of dysplasia was divided into low-grade CAG and high-grade CAG. The degree of glandular expansion was divided into simple expansion and atypia expansion. Glandular atrophy occurred in the glandular glands below the glandular neck, mainly characterized by a narrowing of the glands and decreased amount. In those with severe atrophy, most of the glands were lost and the mucosa became thinner. Atrophic areas were often occupied by infiltrating inflammatory cells and proliferating or metaplastic glands. Among them, irregularly distributed residual glands can be seen, sometimes exhibiting cystic expansion. The gland atrophy in the gastric body was mainly characterized as the disappearance and atrophy of parietal cells and main cells. In severe cases, the two cells completely disappeared, so the secretion of gastric acid and pepsin disappeared. The atrophy in the pylorus caused the loss of gastric mucosa and neutral and reduced secretion of mucus. Severe atrophic area also had an atrophic epithelium and concave epithelium, and the small concave became shallower or even flattened. CAG can form a total gastric atrophy as the disease progressed. At this time, the entire gastric mucosa became thinner, and all glands completely disappeared or were replaced by IM.

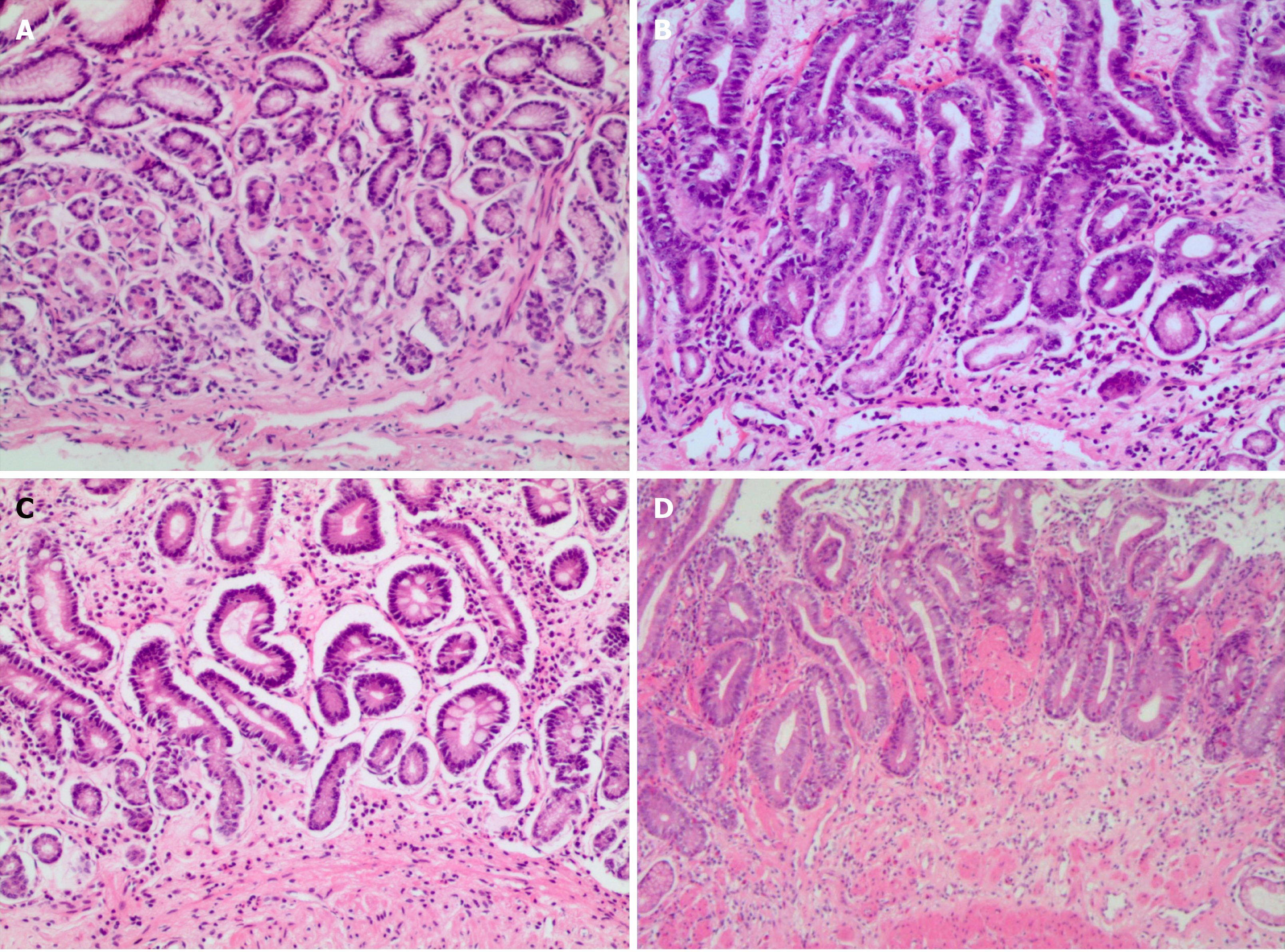

Simple type: The volume of intrinsic glandular layer shrank, the number of glands decreased; the epithelial cell hyperplasia was mild with no atypia; intestinal epithelial metaplasia had no or dispersed single cell or focal small intestine epithelial metaplasia; the glandular dilation was not obvious or there was very little simple glandular dilation; the properties of mucus had not changed significantly, but neutral mucus secretion was reduced; chronic inflammatory cell infiltration can be mild or severe (Figure 1A).

Hyperplasia type: Intrinsic glandular atrophy was accompanied by glandular hyperplasia, and showed a relatively concentrated phenomenon; hyperplasia of the glands did not have a atypia; intestinal epithelial metaplasia had no or dispersed single cell or focal small intestine epithelial metaplasia; there was slight dilation of the glands, little change in the property of the mucus, decreased neutral mucus, increased neutral mucus secretion, and severe inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 1B).

IM type: The atrophy of the lamina propria was accompanied by IM, which was divided into small IM and large IM. According to the degree of IM, it was divided into: Scattered single cell, focal, and extensive IM. IM also varied depending on the property of the mucus, distinguishing between sialic acid mucus and/or sulphate mucus; inflammatory cell infiltration can be mild and severe (Figure 1C).

IEN type: Intrinsic glandular atrophy was accompanied by IEN and high-grade or low-grade IEN; there was intestinal epithelial metaplasia or absence, as dispersed single cell or focal small intestine (or large intestine) epithelial metaplasia; glandular dilatation had no or rarely shaped dilation, accompanied by abnormal dilation with or without atypical expansion of glands, including adenoma-like hyperplasia and/or cystic adenoid hyperplasia; mucus secretion decreased; inflammatory cell infiltration was dominated by lymphocytes (Figure 1D).

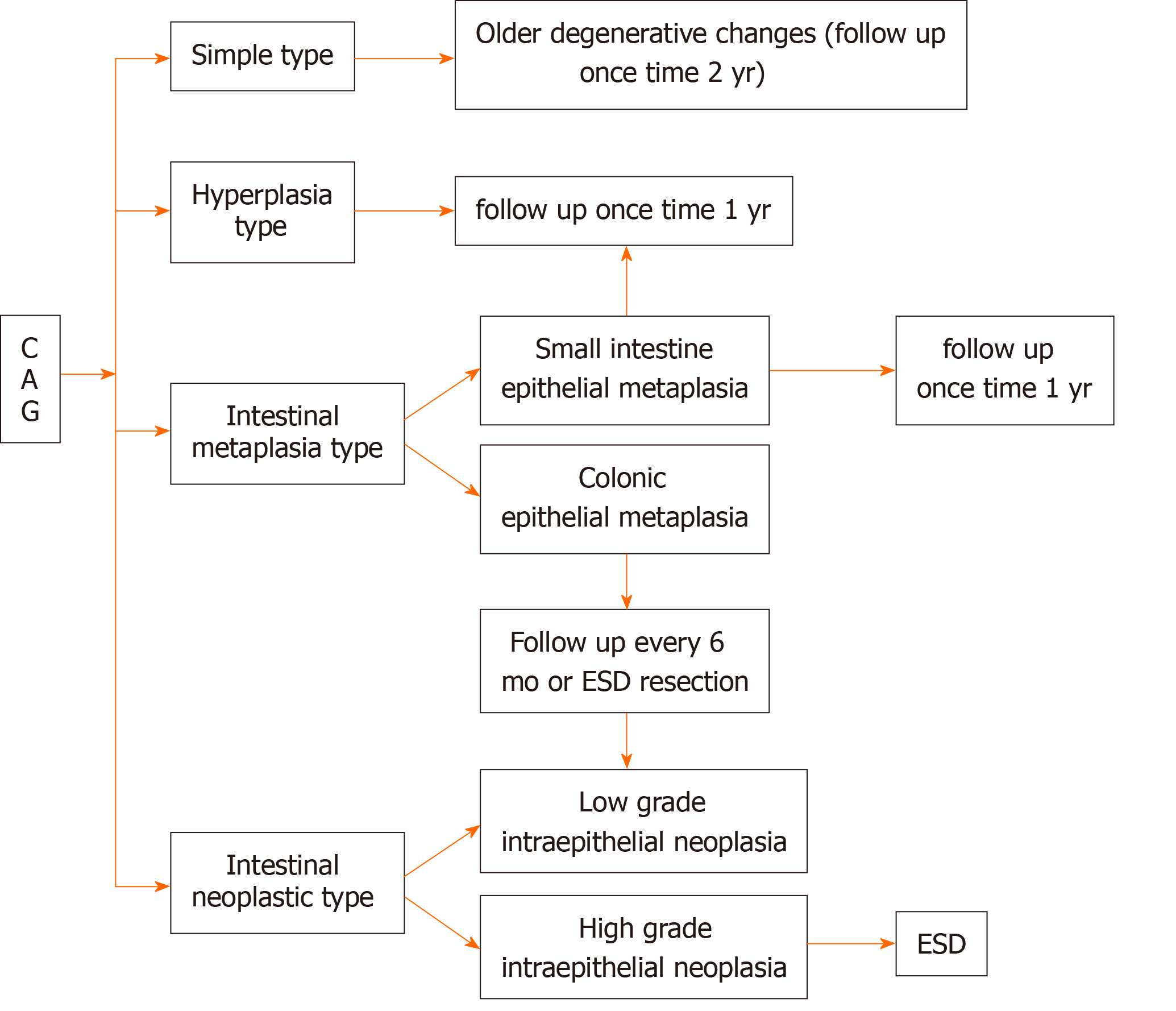

Of the 205 (9.1%) cases of simple CAG followed, 9 (4.4%) were cured, 149 (72.7%) were slightly improved, and 47 (22.9%) were aggravated. Of the 654 (29.1%) cases of hyperplasia type CAG followed, 173 (37.9%) were cured, 339 (51.8%) were slightly improved, and 142 (21.7%) were aggravated. Of the 1132 (50.4%) cases of IM type CAG followed, 87 (7.7%) were improved, 851 (75.2%) were slightly improved, and 194 (17.1%) were aggravated. Of the 257 cases of IEN type CAG (11.4%) followed, 13 (5.1%) were improved, 197 (76.7%) were slightly improved, and 48 (18.7%) were aggravated. The data are shown in Table 2. Based on the results of the follow-up and the actual progression of the disease, we recommend the follow-up time for different types of CAG (Figure 2).

| Group | Simple type (205 cases) | Hyperplasia type (654 cases) | Intestinal epithelial metaplasia type (1132 cases) | Intraepithelial neoplasia type (257cases) | ||||||||

| Cured | Slightly improved | Aggravated | Cured | Slightly improved | Aggravated | Cured | Slightly improved | Aggravated | Cured | Slightly improved | Aggravated | |

| 1-3 mo | 3 | 1 | 32 | 94 | 11 | 16 | 187 | 14 | 2 | 28 | 6 | |

| 4-6 mo | 2 | 47 | 14 | 91 | 149 | 67 | 31 | 435 | 75 | 10 | 113 | 27 |

| 7-12 mo | 7 | 99 | 32 | 50 | 96 | 94 | 40 | 229 | 105 | 1 | 56 | 15 |

| Total (%) | 9 (4.4) | 149 (72.7) | 47 (22.9) | 173 (37.9) | 339 (51.8) | 142 (21.7) | 87 (7.7) | 851 (75.2) | 194 (17.1) | 13 (5.1) | 197 (76.7) | 48 (18.7) |

CAG has a variety of tissue patterns, mainly showing thinning of the gastric mucosa, shorter inherent glandular glands, reduced numbers, decreased function, epithelial cell hyperplasia, IM, inflammatory cell infiltration, etc.[7-11]. In the atrophy area, there may be a large amount of infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells, often spreading to the entire layer of the mucosa, forming lymphoid follicles. IM is a common pathological change in atrophic gastritis[12-15]. It is not comprehensive to report only mild, moderate, and severe CAG in clinical pathologic diagnosis. In addition to the degree of atrophy, CAG also has different types of tissue morphology, such as whether the glands have dilated and/or branched changes, whether there is an increase or decrease in mucous secretion in the glandular cavity, the mucus in the glandular cavity is neutral or acidic, Helicobacter pylori infection and extent, the type and extent of inflammatory cell infiltration[16,17], the degree of compensatory hyperplasia of cells, the existence of typical hyperplasia, and the classification of intracellular tumor change, especially the type and degree of metaplasia. Because intestinal epithelial metaplasia has a brush border that does not secrete mucus and a brush border of goblet cells and absorption cells with acidic mucin[18,19]. A frequency of once a year followed up were performed. Colonic epithelial metaplasia has a brush border of metaplastic cells which is lack of development, disordered arrangement of goblet cells, and irregular shape (intestinal and immature intermediate mucus cells), and acidic saliva mucus and sulfuric acid mucus. The metaplastic cells were extensive so that the risk of gastric cancer increased greatly. Follow-up should be performed twice a year or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) should be performed.

The mild, moderate, and severe classification of CAG does not reflect many tissue morphological features. Therefore, in order to facilitate the guidance of clinical treatment, to track and research of the relationship between CAG and cancer, to target follow-up observation, and to improve the detection rate of early gastric cancer, we proposed the histopathological classification of CAG: Simple type, hyperplasia type, IM type, and IEN type. The simple type is common in the elderly over 60 years old with a stable morphology. It can be regarded as senile degenerative changes, showing glandular atrophy, decreased function, and decreased mucus secretion, which belongs to quantitative changes. The hyperplasia type mostly occurs in people between 40-60 years old[20]. Commonly, lesions are limited to quantitative changes with increased mucus secretion. The lesions can be alleviated or cured after positive treatment[21]. The cases of the IM type increase with the age, especially among those over 50 years old[22]. Mucus secretion has not only a quantitative change but also a qualitative change, containing varying degrees of salivary acid mucus and (or) sulfuric acid mucus[23]. The lesion is hard to alleviate and has a trend to aggravation, therefore close follow-up should be performed. The IEN type is commonly developed from the previous several types[23]. The severe atrophy of glands forms low-grade or high-grade IEN. Decrease of mucus secretion is an essential marker for the precancerous lesion. ESD is recommended[24].

Differential diagnosis: (1) Gastric mucosal focal IM or atrophy: In adult gastric pylorus, most patients had Helicobacter pylori infection, accompanied by IM. Obviously, it is not appropriate to diagnose as GAS. Diagnosis of atrophic gastritis means a change in gastric function and an increased risk of cancer. In the absence of guidelines, it is recommended that if the area of focal intrinsic glandular atrophy or metaplasia is less than 0.5 mm, physicians only describe the extent of atrophic or intestinal lesions, not to report CAG. The decision is made after the follow-up review[25,26]; (2) Non-atrophic IEN: confirm of flat non-atrophic IEN should be closely combined with clinical and endoscopic findings. The lesions are mostly patchy and localized. CAG initially occurred in the angular incisura, and then distributed along the junction of the both sides of lesser curvature and gastric pylorus and gastric body, showing an inverted V-shaped shape. Histological around the IEN showed atrophic areas; (3) Hyperplastic polyps: There were distorted irregular glands histologically, cells showed hyperplasia active, which were usually rich in mucin, with reduced focal mucin. Hyperplasia polyps can be seen in IM. Hyperplasia polyps also contain thin smooth muscle fibers, usually extended from the base of polyps to the surface[27,28]; And (4) repairing lesions of gastric mucosal erosion or ulcer: the lesion has patchy compensatory glandular hyperplasia, the glandular epithelial cells of repaired hyperplasia are low columnar, the cytoplasm lacks mucus, the nucleus increases, and the chromatin is deeply stained. Fibrous tissue was proliferated. Lesions are multi-focal, and the area of hyperplasia usually does not exceed 0.5 mm. This type of lesion can restore the structure and function of the original normal tissue, more importantly, there is a certain limit to this kind of repair lesion, once the cause of hyperplasia is eliminated, the lesion will stop growth.

Considering the current research results, we suggest that the mild, moderate, and severe classification of CAG only describes gland atrophy and mucosal thinning, ignoring the relationship between malignant transformation of cells, histomor

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is a common lesion in gastric mucosal biopsy tissue. The classification of CAG into the mild, moderate, and severe cannot reflect the histomorphology characteristics. Moreover, this classification only describes gland atrophy and mucosal thinning, ignoring the relationship between malignant transformation of cells, histomorphology findings, and early gastric cancer.

The old classification system is not appropriate in actual work, and there are often some exceptions.

To develop a new classification system in practical work.

To observe the role of the new classification in clinical application from the clinical manifestations, histopathological morphology, and follow-up review.

Each of the four classifications has its own characteristics. The definition and pictures are given in the article, which is more practical than the previous classification system.

This study divides CAG into four types: Simple, hyperplastic, intestinal metaplasia, and intraepithelial neoplasia types. This classification is based on the morphological characteristics of gastric mucosal atrophy in the clinical pathology report. Moreover, the recommended follow-up time is proposed.

Future research should be undertaken to assess the clinical effects of applying this classification to more samples. The new classification has an appreciated effect in preventing atrophic gastritis from developing into gastric cancer.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E, E

P-Reviewer: Aydin M, Grotz TE, Ribeiro IB S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Massironi S, Cavalcoli F, Zilli A, Del Gobbo A, Ciafardini C, Bernasconi S, Felicetta I, Conte D, Peracchi M. Relevance of vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: a prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bordi C, Annibale B, Azzoni C, Marignani M, Ferraro G, Antonelli G, D'Adda T, D'Ambra G, Delle Fave G. Endocrine cell growths in atrophic body gastritis. Critical evaluation of a histological classification. J Pathol. 1997;182:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kaklikkaya N, Cubukcu K, Aydin F, Bakir T, Erkul S, Tosun I, Topbas M, Yazici Y, Buruk CK, Erturk M. Significance of cagA status and vacA subtypes of Helicobacter pylori in determining gastric histopathology: virulence markers of H. pylori and histopathology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1042-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mäkinen JM, Niemelä S, Kerola T, Lehtola J, Karttunen TJ. Epithelial cell proliferation and glandular atrophy in lymphocytic gastritis: effect of H pylori treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2706-2710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Genta RM. Review article: Gastric atrophy and atrophic gastritis--nebulous concepts in search of a definition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12 Suppl 1:17-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yabuki K, Haratake J, Tsuda Y, Shiba E, Harada H, Yorita K, Uchihashi K, Matsuyama A, Hirata K, Hisaoka M. Lanthanum-Induced Mucosal Alterations in the Stomach (Lanthanum Gastropathy): a Comparative Study Using an Animal Model. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2018;185:36-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Elloumi H, Sabbah M, Debbiche A, Ouakaa A, Bibani N, Trad D, Gargouri D, Kharrat J. Systematic gastric biopsy in iron deficiency anaemia. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2017;18:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miki A, Yamamoto T, Maruyama K, Nakamura N, Aoyagi H, Isono A, Abe K, Kita H. Extensive gastric mucosal atrophy is a possible predictor of clinical effectiveness of acotiamide in patients with functional dyspepsia . Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;55:901-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Draşovean SC, Boeriu AM, Akabah PS, Mocan SL, Pascarenco OD, Dobru ED. Optical biopsy strategy for the assessment of atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2018;59:505-512. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kinoshita H, Hayakawa Y, Konishi M, Hata M, Tsuboi M, Hayata Y, Hikiba Y, Ihara S, Nakagawa H, Ikenoue T, Ushiku T, Fukayama M, Hirata Y, Koike K. Three types of metaplasia model through Kras activation, Pten deletion, or Cdh1 deletion in the gastric epithelium. J Pathol. 2019;247:35-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Choi AY, Strate LL, Fix MC, Schmidt RA, Ende AR, Yeh MM, Inadomi JM, Hwang JH. Association of gastric intestinal metaplasia and East Asian ethnicity with the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a U.S. population. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1023-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toyoshima O, Nishizawa T, Sakitani K, Yamakawa T, Takahashi Y, Yamamichi N, Hata K, Seto Y, Koike K, Watanabe H, Suzuki H. Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori antibody titer and its association with gastric nodularity, atrophy, and age: A cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4061-4068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hamedi Asl D, Naserpour Farivar T, Rahmani B, Hajmanoochehri F, Emami Razavi AN, Jahanbin B, Soleimani Dodaran M, Peymani A. The role of transferrin receptor in the Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis; L-ferritin as a novel marker for intestinal metaplasia. Microb Pathog. 2019;126:157-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sung J, Kim N, Lee J, Hwang YJ, Kim HW, Chung JW, Kim JW, Lee DH. Associations among Gastric Juice pH, Atrophic Gastritis, Intestinal Metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori Infection. Gut Liver. 2018;12:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Koh JS, Joo MK. Helicobacter pylori eradication in the treatment of gastric hyperplastic polyps: beyond National Health Insurance. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33:490-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Matysiak-Budnik T, Camargo MC, Piazuelo MB, Leja M. Recent Guidelines on the Management of Patients with Gastric Atrophy: Common Points and Controversies. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:1899-1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Crafa P, Russo M, Miraglia C, Barchi A, Moccia F, Nouvenne A, Leandro G, Meschi T, De' Angelis GL, Di Mario F. From Sidney to OLGA: an overview of atrophic gastritis. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shah SC, Gawron AJ, Mustafa RA, Piazuelo MB. Histologic Subtyping of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia: Overview and Considerations for Clinical Practice. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:745-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Trieu JA, Bilal M, Saraireh H, Wang AY. Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:1079-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tian SF, Xiong YY, Yu SP, Lan J. [Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and expressions of tumor suppressor genes in gastric carcinoma and related lesions]. Aizheng. 2002;21:970-973. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Doganavsargil B, Sarsik B, Kirdok FS, Musoglu A, Tuncyurek M. p21 and p27 immunoexpression in gastric well differentiated endocrine tumors (ECL-cell carcinoids). World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6280-6284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li TT, Qiu F, Qian ZR, Wan J, Qi XK, Wu BY. Classification, clinicopathologic features and treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wang YK. Gastric nonneoplastic lesions. In: Gao CF, Wang YK. Digestive system disease diagnosis and treatment. Beijing: People's Military Medical Publishing House, 2016: 581-687. |

| 24. | Wang YK. Gastric tumor pathology. In: Gao CF, Wang YK. Digestive oncology. Beijing: People's Military Medical Publishing House, 2012: 296-404. |

| 25. | Park SH, Kangwan N, Park JM, Kim EH, Hahm KB. Non-microbial approach for Helicobacter pylori as faster track to prevent gastric cancer than simple eradication. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8986-8995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Negovan A, Iancu M, Fülöp E, Bănescu C. Helicobacter pylori and cytokine gene variants as predictors of premalignant gastric lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4105-4124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sokic-Milutinovic A, Alempijevic T, Milosavljevic T. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric carcinogenesis: Current knowledge and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11654-11672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Kang KH, Hwang SH, Kim D, Kim DH, Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Koo JS, Jung YK, Yim HJ, Lee SW. [The Effect of Helicobacter pylori Infection on Recurrence of Gastric Hyperplastic Polyp after Endoscopic Removal]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2018;71:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |