Published online Apr 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2937

Peer-review started: December 31, 2020

First decision: January 17, 2021

Revised: January 27, 2021

Accepted: February 8, 2021

Article in press: February 8, 2021

Published online: April 26, 2021

Processing time: 104 Days and 13.2 Hours

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare heterogeneous liver disease characterized by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract. The incidence of BCS is so low that it is difficult to detect in general practice and difficult to include within the scope of routine diagnosis. The clinical manifestations of BCS are not specific; hence, BCS tends to be misdiagnosed.

We report the case of a 33-year-old Chinese woman who presented with progressive distension in the upper abdomen. She was initially misdiagnosed with liver cirrhosis (LC) due to abnormalities on an upper abdominal computed tomography scan. Although she was taking standard anti-cirrhosis therapy, her symptoms did not improve. Magnetic resonance imaging showed caudate lobe hypertrophy; and dilated lumbar and hemiazygos veins. Venography revealed membranous obstruction of the inferior vena cava owing to congenital vascular malformation. A definitive diagnosis of BCS was made. Balloon angioplasty was performed to recanalize the obstructed inferior vena cava and the patient’s symptoms were completely resolved.

BCS lacks specific clinical features and can eventually lead to LC. Clinicians and radiologists must carefully differentiate BCS from LC. Correct diagnosis and timely treatment are vital to the patient's health.

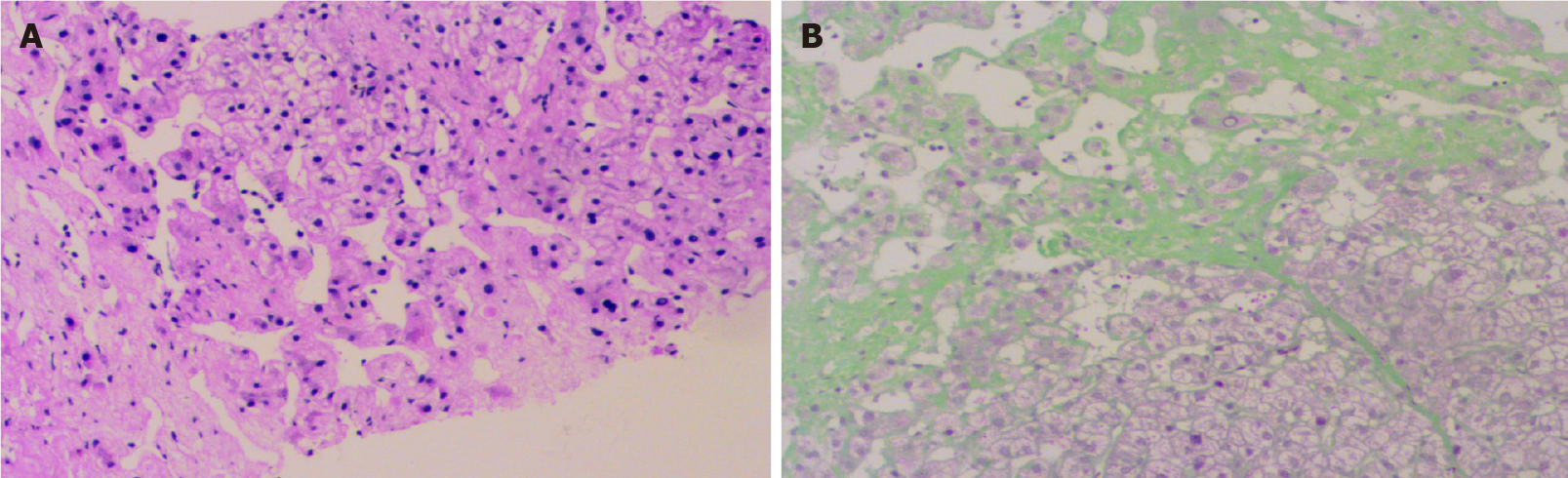

Core Tip: Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare heterogeneous liver disease cha-racterized by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract. We report a case of BCS initially misdiagnosed as liver cirrhosis due to the abnormalities visible on an upper abdominal computed tomography scan. Further examinations were performed to establish a diagnosis. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a narrowed inferior vena cava. Liver biopsy and pathological analysis showed hepatocyte degeneration, bridging fibrosis, sinusoidal dilatation, and areas of fibrous tissue with substantial hyperplasia, suggesting that BCS was the cause of liver cirrhosis.

- Citation: Ye QB, Huang QF, Luo YC, Wen YL, Chen ZK, Wei AL. Budd-Chiari syndrome associated with liver cirrhosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(12): 2937-2943

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i12/2937.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i12.2937

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a rare heterogeneous liver disease that is characterized by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract, which may occur anywhere from the small hepatic veins (HVs) to the inferior vena cava (IVC) and right atrium[1]. According to the location of the obstruction, BCS can be classified as involving the small HVs, large HVs, IVC, or arbitrary combinations of these[2]. BCS can eventually lead to sinusoidal congestion, portal hypertension, liver cell injury, centrilobular fibrosis, and ultimately, cirrhosis[3]. The incidence rate of BCS varies among countries. In China, the annual incidence rate of BCS in the five areas with the highest prevalence is estimated to be 0.88 per million[4]. The rate of liver cirrhosis (LC) caused by BCS is approximately 4%[5]. Due to its low incidence, BCS is difficult to detect in general practice and to include within the scope of routine diagnosis. Moreover, the clinical manifestations of BCS are abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, and ascites, which are also frequently seen in LC; thus, BCS tends to be misdiagnosed.

Here, we report a case of BCS associated with cirrhosis, which was initially misdiagnosed.

A 33-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to our medical institution on May 21, 2018, owing to progressive distension in the upper abdomen.

Two weeks before admission, she was diagnosed with LC, portal hypertension and splenomegaly, based on an upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan at another hospital. Although she was taking prescribed medication that exerted effects such as anti-hepatic fibrosis, inhibition of gastric acid secretion, and protection of the stomach, her symptoms did not improve. She developed progressive distension in the upper abdomen with sour regurgitation. There was no nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain.

The patient had a history of thrombocytopenia going back more than 10 years and she had undergone surgery for an ovarian cyst on the left side in 2011.

No special personal and family history.

Physical examination revealed dark discoloration and mild tenderness in the left lower abdomen; other examinations were normal.

Complete blood cell count showed a reduced white blood cell count 3.1 × 109/L (normal range 3.5-9.5 × 109/L) and platelet count 74 × 109/L (normal range 125-350 × 109/L). Liver and renal functions, coagulation, and tumor markers were normal. Serum electrolytes were within the normal range. The levels of protein C, protein S, immunoglobulin (Ig) G, IgA, and IgM were also within normal limits. Serology for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody, anticardiolipin antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant was negative. No other obvious abnormalities were discovered.

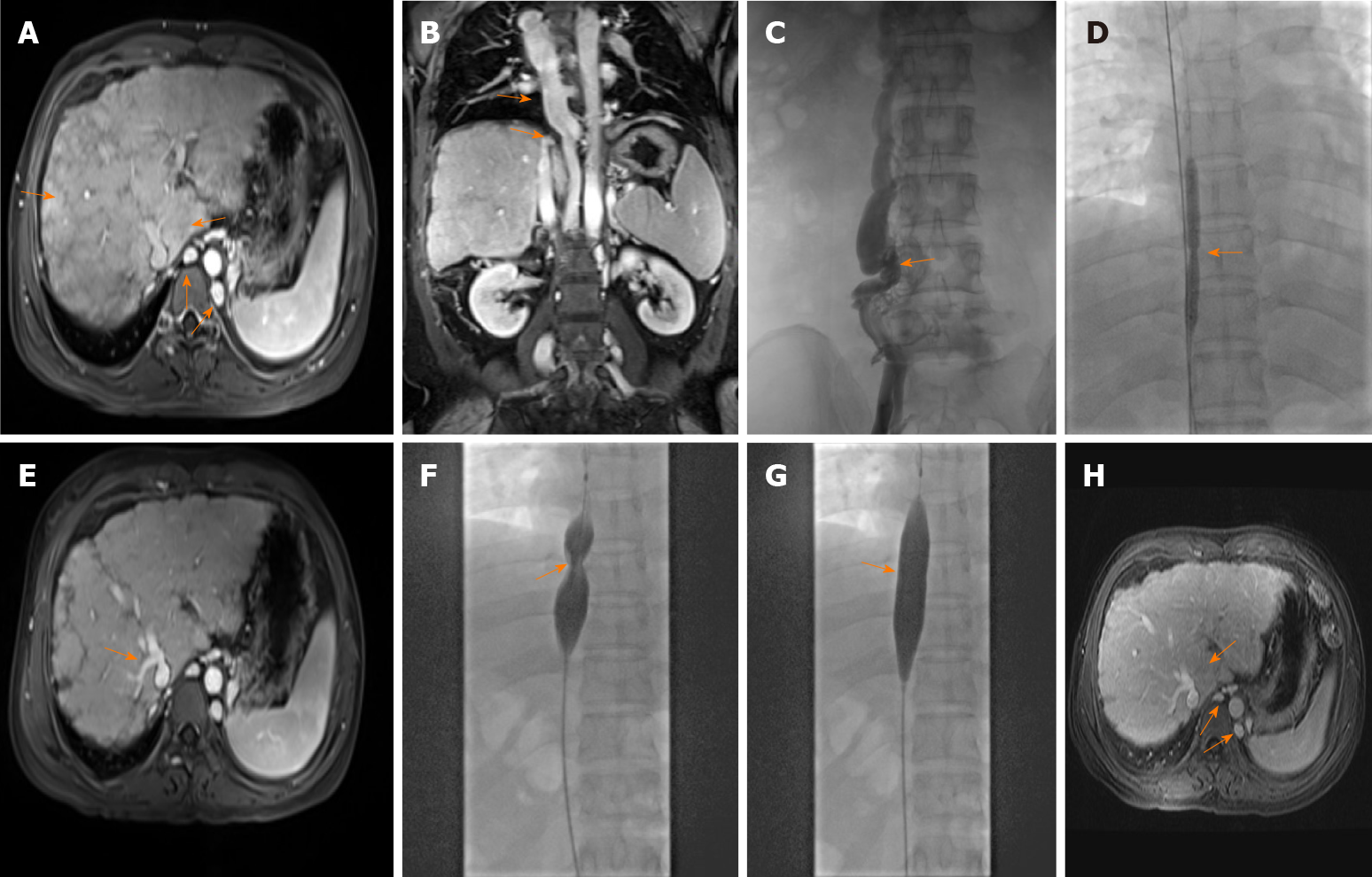

Gastroscopy showed mild esophageal varices. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed caudate lobe hypertrophy, cirrhosis, and dilated lumbar and hemiazygos veins (Figure 1A). Dilated azygos veins and narrowed IVC were present (Figure 1B). Hypersplenotrophy and dilated veins in the lower esophagus and surrounding the hilus lienis were also observed.

To confirm the diagnosis of BCS, liver biopsy was performed under CT guidance. Histochemical staining (hematoxylin-eosin and Masson trichrome) showed hepatocyte degeneration, bridging fibrosis, sinusoidal dilatation, and areas of fibrous tissue with substantial hyperplasia (Figure 2).

The definitive diagnosis in this patient was BCS, compensated LC, and thrombopenia.

Venography of the HVs and IVC via the femoral vein and internal jugular vein revealed complete occlusion of the IVC with the formation of numerous collateral branches (Figure 1C). Balloon angioplasty was performed to recanalize the obstructed IVC (Figure 1D) on June 19, 2018. The administration of anti-hepatic fibrosis medication was continued. Three months after balloon angioplasty, the patient again presented with upper abdominal distension and pain and was readmitted to our hospital. MRI showed HV stenosis with ectopic tissue (Figure 1E). The obstructed IVC was treated with balloon dilation angioplasty (Figure 1F and G) on October 23, 2018.

Six months after balloon angioplasty, the patient’s MRI revealed that dilation of the lumbar and hemiazygos veins and caudate lobe hypertrophy were improved (Figure 1H). In addition, venography of the IVC combined with hepatic venous pressure measurement was performed. The results showed that the pressure was 12 mmHg. Furthermore, liver function tests were normal.

BCS is a relatively rare vascular disorder among liver diseases. It is characterized by obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract and may lead to congestion in the liver. Chronic hepatic congestion can eventually result in liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. BCS is divided into four classifications involving small HVs, large HVs, the IVC, and arbitrary combinations of these according to the venous stenosis site. The distribution of BCS varies geographically. IVC with or without HV obstruction is predominant in Asia, whereas HV obstruction predominates in Western countries[6]. In terms of age and sex, BCS tends to be more common in females than males and to mostly appear at the age of 20-39 years[7].

A number of causes of BCS have been identified. According to etiology, BCS can be divided into primary BCS and secondary BCS. Risk factors for the former include hypercoagulable states and thrombosis, which may be caused by myeloproliferative disorders, antiphospholipid syndrome, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, hyperhomocysteinemia, Behçet disease, protein C deficiency, and protein S deficiency, among others. Risk factors for secondary BCS are predominantly tumoral invasion, abscesses, and cysts[8]. Vascular thrombosis is the most common element resulting in obstruction of the HV system, as reported in a long-term follow-up study[9]. However, more potential risk factors or causes of BCS should be investigated clinically.

Classical clinical manifestations of BCS include abdominal pain, ascites, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and leg swelling[10,11]. Up to 20% of patients with BCS are asymptomatic[12]. In our report, the main complaint in this patient was upper abdominal distension and pain. Nevertheless, this finding was not specific; these symptoms or other classical clinical manifestations may be observed in progressive liver diseases. Hence, in addition to symptoms and signs, diagnostic techniques and the skill of the physician are important in the diagnosis of BCS.

There are various auxiliary examinations for diagnosing BCS. In some cases, serum aminotransferases and bilirubin can be obviously increased, and albumin is decreased. However, laboratory findings may also show that liver function or other indicators are normal. Under these circumstances, radiological methods are helpful for further diagnosis. Doppler ultrasound, CT, and MRI are the main diagnostic methods. Although the sensitivity of ultrasound is as high as 87%[13], BCS can be excluded relatively easily using ultrasound in comparison with CT/MRI, which can reveal abnormal changes in vessels of the liver. CT is limited owing to its uncertain results in nearly 50% of cases[14]. In fact, most patients with BCS can be diagnosed if the radiologist and clinician carefully examine the imaging features of BCS. MRI along with intravenous gadolinium injection has an advantage in the visualization of HVs, IVC, large intrahepatic or comma-shaped collateral vessels, and spider web networks. Thus, MRI is a reasonable choice for the diagnosis of BCS.

Liver biopsy is not a routine diagnostic requirement. However, when imaging does not show the obstruction of venous outflow or BCS is suspected, liver biopsy is required. Liver biopsy may demonstrate liver cell loss, congestion, and fibrosis. In addition, liver biopsy is helpful for differentiating between BCS and veno-occlusive disease. It should be noted that congestion can be found in constrictive pericarditis and cardiac failure, and fibrosis can indicate other diseases, such as diabetes. These similar clinical characteristics should be identified.

Venography can be considered as a diagnostic procedure when the diagnosis of BCS remains unclear. At the same time, valuable information, including the degree of thrombosis, assessment of HVs, and caval pressures, can be provided by venography, to help in the choice of optimal treatment. The portal vein can also be evaluated in this procedure. Venous pressure measurements are conducive to treatment options under various circumstances. For example, to relieve cirrhosis, dilation of HV stenosis is performed to reduce pressure of the HV. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is performed to decrease pressure of the portal vein, which is conducive to the regression of ascites and can effectively prevent bleeding via embolization of varicose collateral vessels in the same sitting. Furthermore, venous pressure measurements are helpful for assessing the patient's condition in postoperative follow-up.

BCS has a standard management and appraisal system based on guidelines. Specifically, the first-line therapy is medical treatment, which is administered to patients with a hypercoagulable state, portal hypertension, basic diseases, or related complications. The second-line therapy is angioplasty or stenting, which is appropriate for patients with short-length stenosis after medical therapy failure. The next step in management is TIPS, which is suitable for patients who do not respond to medical, angioplasty, or stenting treatment. Liver transplant is the last step in management and has strict requirements, being suitable only for patients with LC, advanced liver dysfunction, or fulminant hepatic failure[15]. It has been reported that the long-term survival rate of liver transplant is approximately 84%[16].

In our patient, the causes and classical clinical features of BCS were not recognized. BCS was diagnosed by MRI findings, which showed a narrowed IVC, caudate lobe hypertrophy, and dilated lumbar vein, azygos veins, and hemiazygos veins. Cavography confirmed IVC obstruction in this patient. Short-length stenosis is found in approximately 60% of patients with obstructive IVC[17]. In theory, patients with segmental or focal block of the HV outflow tract are suitable for recanalization. Recanalization of the IVC with balloon angioplasty can improve the clinical presentation. The short-term effect is satisfactory, but the restenosis rate is as high as 50% at 2 years after angioplasty[18]. Therapy using stents could prolong the long-term patency rates[19]. Stent implantation should be considered for patients with an unsatisfactory curative effect or recurrent restenosis. However, the disadvantage of stent treatment should not be underestimated. The clinician should choose the best therapy according to the patient's condition.

The ultimate therapeutic purpose of various clinical treatment methods is to remove the diseased HV/IVC; restore normal blood flow; relieve portal hypertension, stasis cirrhosis, or IVC hypertension syndrome; improve the quality of life of patients; and prolong survival. Balloon angioplasty is one of the procedures used to recanalize the obstruction of the hepatic venous outflow tract. However, the occurrence of postoperative restenosis has serious effects on the long-term curative effects. In our report, with regard to the possible cause of the first three-month re-stenosis, we concluded that the following causes were possible. First, the diameter of the balloon catheter used in balloon angioplasty was not optimal, and the medical community has not yet set a standard for the size of the balloon in balloon angioplasty. Second, inductive vascular repair after balloon angioplasty resulted in thickening of the intima and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in the media. To prevent recurrence, we should maximize treatment efficacy. Specifically, selection of the balloon diameter is key. It affects the clinical efficacy and the recurrence of postoperative lesions. Selection of the appropriate balloon diameter should be fully evaluated in preoperative planning. During the operation, the surgeon should fully dilate the stenosis or occlusion of the IVC, tear the septum, and loosen the thickened venous wall and extravascular fibrous connective tissue to improve the efficacy and reduce the postoperative recurrence rate.

One point that should be noted is that LC was secondary to BCS in this case, as the common causes of cirrhosis had been ruled out. Owing to its rarity as a cause of LC, a diagnosis of BCS may be overlooked by inexperienced clinicians. A detailed medical history, clinical presentations, physical examination, and imaging findings or liver biopsy should be used to make a diagnosis. Moreover, BCS should be differentiated from other similar diseases, such as congestive hepatopathy. Correct diagnosis will avoid missing the optimal therapy time and prolonging the condition. Theoretically, chronic liver congestion in patients with BCS is the main factor leading to the development of LC. Greater attention is needed for the timely treatment of BCS before its progression to LC.

We describe a case of BCS, in which the obstruction site was the IVC. BCS is relatively easy to misdiagnose or overlook owing to its rarity. Clinicians and radiologists must carefully differentiate BCS from LC. Particularly when patients with LC present with unknown causes and normal liver function, the possibility of BCS should be considered. Correct diagnosis and timely treatment can affect the therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, recanalization before the formation of hepatocirrhosis is vital to prevent or reverse hepatic fibrosis.

We thank the patient and her family for their support.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kadriyan H S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Valla DC. The diagnosis and management of the Budd-Chiari syndrome: consensus and controversies. Hepatology. 2003;38:793-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ludwig J, Hashimoto E, McGill DB, van Heerden JA. Classification of hepatic venous outflow obstruction: ambiguous terminology of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Menon KV, Shah V, Kamath PS. The Budd-Chiari syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang W, Qi X, Zhang X, Su H, Zhong H, Shi J, Xu K. Budd-Chiari Syndrome in China: A Systematic Analysis of Epidemiological Features Based on the Chinese Literature Survey. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:738548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Wang X, Lin SX, Tao J, Wei XQ, Liu YT, Chen YM, Wu B. Study of liver cirrhosis over ten consecutive years in Southern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13546-13555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Valla DC. Hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction etiopathogenesis: Asia vs the West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:S204-S211. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Seijo S, Plessier A, Hoekstra J, Dell'era A, Mandair D, Rifai K, Trebicka J, Morard I, Lasser L, Abraldes JG, Darwish Murad S, Heller J, Hadengue A, Primignani M, Elias E, Janssen HL, Valla DC, Garcia-Pagan JC; European Network for Vascular Disorders of the Liver. Good long-term outcome of Budd-Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology. 2013;57:1962-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G; American Association for the Study Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1729-1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harmanci O, Kav T, Peynircioglu B, Buyukasik Y, Sokmensuer C, Bayraktar Y. Long-term follow-up study in Budd-Chiari syndrome: single-center experience in 22 years. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Okuda H, Yamagata H, Obata H, Iwata H, Sasaki R, Imai F, Okudaira M, Ohbu M, Okuda K. Epidemiological and clinical features of Budd-Chiari syndrome in Japan. J Hepatol. 1995;22:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Darwish Murad S, Valla DC, de Groen PC, Zeitoun G, Hopmans JA, Haagsma EB, van Hoek B, Hansen BE, Rosendaal FR, Janssen HL. Determinants of survival and the effect of portosystemic shunting in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatology. 2004;39:500-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hadengue A, Poliquin M, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J, Degott C, Erlinger S, Benhamou JP. The changing scene of hepatic vein thrombosis: recognition of asymptomatic cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1042-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bolondi L, Gaiani S, Li Bassi S, Zironi G, Bonino F, Brunetto M, Barbara L. Diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome by pulsed Doppler ultrasound. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1324-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gupta S, Barter S, Phillips GW, Gibson RN, Hodgson HJ. Comparison of ultrasonography, computed tomography and 99mTc liver scan in diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Gut. 1987;28:242-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ringe B, Lang H, Oldhafer KJ, Gebel M, Flemming P, Georgii A, Borst HG, Pichlmayr R. Which is the best surgery for Budd-Chiari syndrome: venous decompression or liver transplantation? Hepatology. 1995;21:1337-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Srinivasan P, Rela M, Prachalias A, Muiesan P, Portmann B, Mufti GJ, Pagliuca A, O'Grady J, Heaton N. Liver transplantation for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Transplantation. 2002;73:973-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Okuda K. Inferior vena cava thrombosis at its hepatic portion (obliterative hepatocavopathy). Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:15-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu K, He FX, Zhang HG, Zhang XT, Han MJ, Wang CR, Kaneko M, Takahashi M, Okawada T. Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by obstruction of the hepatic inferior vena cava: immediate and 2-year treatment results of transluminal angioplasty and metallic stent placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang CQ, Fu LN, Xu L, Zhang GQ, Jia T, Liu JY, Qin CY, Zhu JR. Long-term effect of stent placement in 115 patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2587-2591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |