Published online Mar 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1026

Peer-review started: December 20, 2019

First decision: January 7, 2020

Revised: January 15, 2020

Accepted: March 5, 2020

Article in press: March 5, 2020

Published online: March 26, 2020

Processing time: 96 Days and 23.2 Hours

Distal esophageal spasm (DES) is a rare major motility disorder in the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders (CC). DES is diagnosed by finding of ≥ 20% premature contractions, with normal lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation on high-resolution manometry (HRM) in the latest version of CCv3.0. This feature differentiates it from achalasia type 3, which has an elevated LES relaxation pressure. Like other spastic esophageal disorders, DES has been linked to conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, psychiatric conditions, and narcotic use. In addition to HRM, ancillary tests such as endoscopy and barium esophagram can provide supplemental information to differentiate DES from other conditions. Functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP), a new cutting-edge diagnostic tool, is able to recognize abnormal LES dysfunction that can be missed by HRM and can further guide LES targeted treatment when esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction is diagnosed on FLIP. Medical treatment in DES mostly targets symptomatic relief and often fails. Botulinum toxin injection during endoscopy may provide a temporary therapy that wears off over time. Myotomy through peroral endoscopic myotomy or via surgical Heller myotomy can provide long term relief in cases with persistent symptoms.

Core tip: Distal esophageal spasm (DES) is an esophageal motor disorder that is diagnosed using high-resolution manometry and is classified as a major motility disorder in the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorder. While the criteria for diagnosis have been revised overtime to achieve a homogenous clinical entity, presentation of DES continues to be heterogenous. This has led to the usage of multiple pharmacological treatment options such as nitrates, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and tricyclic antidepressants, often resulting in poor symptom management. DES pathophysiology falls within the spectrum of spastic motility disorders, and it may represent a stage in the process of evolution to achalasia, more likely type 3. Patients who have continued symptoms despite medical management might benefit from endoscopic procedures such as botulinum injection and peroral endoscopic myotomy.

- Citation: Gorti H, Samo S, Shahnavaz N, Qayed E. Distal esophageal spasm: Update on diagnosis and management in the era of high-resolution manometry. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(6): 1026-1032

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i6/1026.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i6.1026

The symptoms of distal esophageal spasm (DES) were first clinically described by Dr. Osgood[1] in 1889. He described six patients with symptoms of sudden chest pain and dysphagia during eating, with eventual sensation of passage of food to the stomach. In 1934, Moersch and Camp[2] used the term “Diffuse spasm of the lower part of the esophagus” to describe findings of abnormal contractions in 8 patients with chest pain and dysphagia. Since then its definition had undergone revision over time with technological advances and improvements in diagnostic evaluation techniques up until its latest definition in the Chicago classification of esophageal motility disorders (CCv3.0) using high-resolution manometry (HRM)[3,4]. Initial reports of this disorder noted tertiary esophageal contractions on esophageal barium studies, which at time held no clinical significance. However, with the increasing occurrence of these findings with symptoms of dysphagia and substernal chest pain[5], this clinical syndrome was later classified as DES. The earliest studies establishing diagnostic criteria characterized the predominant feature of DES to be powerful simultaneous contractions followed by repetitive spasms with intermittent primary peristalsis[5,6]. Later on, with new technological advances and manometric evaluation techniques the definition of DES was revised. In addition to the initial diagnostic feature of simultaneous contractions with intermittent normal peristalsis, an additional criterion of contractions being present for more than 10% of wet swallows was added as it was observed that healthy controls may have such features but with frequency < 10% of swallows[4]. However, the above definitions created a large heterogeneity to this disorder.

The invention of HRM in 2000 significantly improved the ability to understand and evaluate esophageal motility disorders including DES[7]. Multiple studies have been conducted to help decipher the various aspects of this esophageal motility disorder. Currently, the specific characteristics of DES on HRM are premature contractions (≥ 20% of wet swallows) and normal relaxation of lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

DES is thought to result from an imbalance between the nitrogenic inhibitory pathway and the cholinergic excitatory pathway in the myenteric plexus[8-10]. Physiologically, there is a neuronal inhibitory gradient between the proximal and distal esophagus; this gradient increases as the neuronal signal moves to the distal esophagus and towards the LES. This translates to a gradual increase in duration of deglutitive inhibition as the peristaltic wave moves to the distal parts of the esophagus[10]. The interval of deglutitive inhibition was defined as contractile latency; and it was hypothesized that a decrease in this interval would result in spontaneous contractions or spasms[11]. It has also been shown that subjects receiving a nitric oxide (NO) scavenger (recombinant hemoglobin) had abnormalities in the timing of esophageal peristalsis causing simultaneous contractions along the length of smooth muscles and a decrease in contractile latency[8]. This supported the hypothesis that the inhibitory pathway plays a major role in the development of DES and other spastic motility disorders.

As in other esophageal motility disorders like esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO), DES can be seen in association with other conditions. The relationship between DES and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an area of continued debate. Some patients with motility disorders including DES experience improvement or resolution of symptoms after treatment of reflux disease[12], which supports a relation between esophageal acid exposure and esophageal spasticity. DES has also been linked to psychiatric conditions. Clouse et al[13] reported that psychiatric diagnoses were present in 84% (21/25) of patients with abnormal manometric findings such as simultaneous contractions, increased mean wave amplitudes and duration, and other abnormal motor responses. Another retrospective study reported 46% of patients diagnosed with DES were using psychotropic medications for psychiatric conditions and chronic pain, with 31% using anti-depressants[14]. An interesting case study reported a possible correlation between post traumatic abdominal epilepsy presenting as DES with normalization of motor abnormalities after treatment with anti-epilepsy drugs[15]. The authors concluded that in addition to the known pathophysiology of neural impairment, there might exist a central mechanism causing esophageal motor abnormalities in conditions such as anxiety and seizures.

Spastic esophageal disorders including DES are encountered more frequently in the setting of narcotics use[16,17]. This is a clinically relevant point given the current opiates epidemic in the United States. Opiates inhibit the neuronal excitability that leads to secretion of inhibitory neurotransmitters like NO and vasoactive intestinal peptide. This decreases the latency gradient in the distal esophagus, and results in simultaneous high-amplitude contraction (DES); and failure of LES to relax (EGJOO and achalasia type 3)[18]. It has also been shown that esophageal motility disorders can resolve upon opiate withdrawal[17].

Few studies have described the histopathology of DES and other motility disorders. Nakajima et al[19] described a case of DES in a 59 year-old woman showed that the esophageal muscle layer had loss of interstitial cells of Cajal, moderate atrophy and fibrosis, and no inflammation. Other older studies showed no significant difference in muscle layer histopathology between DES and controls[20].

Although DES has been refined into a more homogenous disorder using specific criteria on HRM, its clinical presentation is heterogenous[21]. The most common symptoms of DES include dysphagia (55%) followed by chest pain (29%). Other symptoms may include regurgitation, heartburn, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting[14].

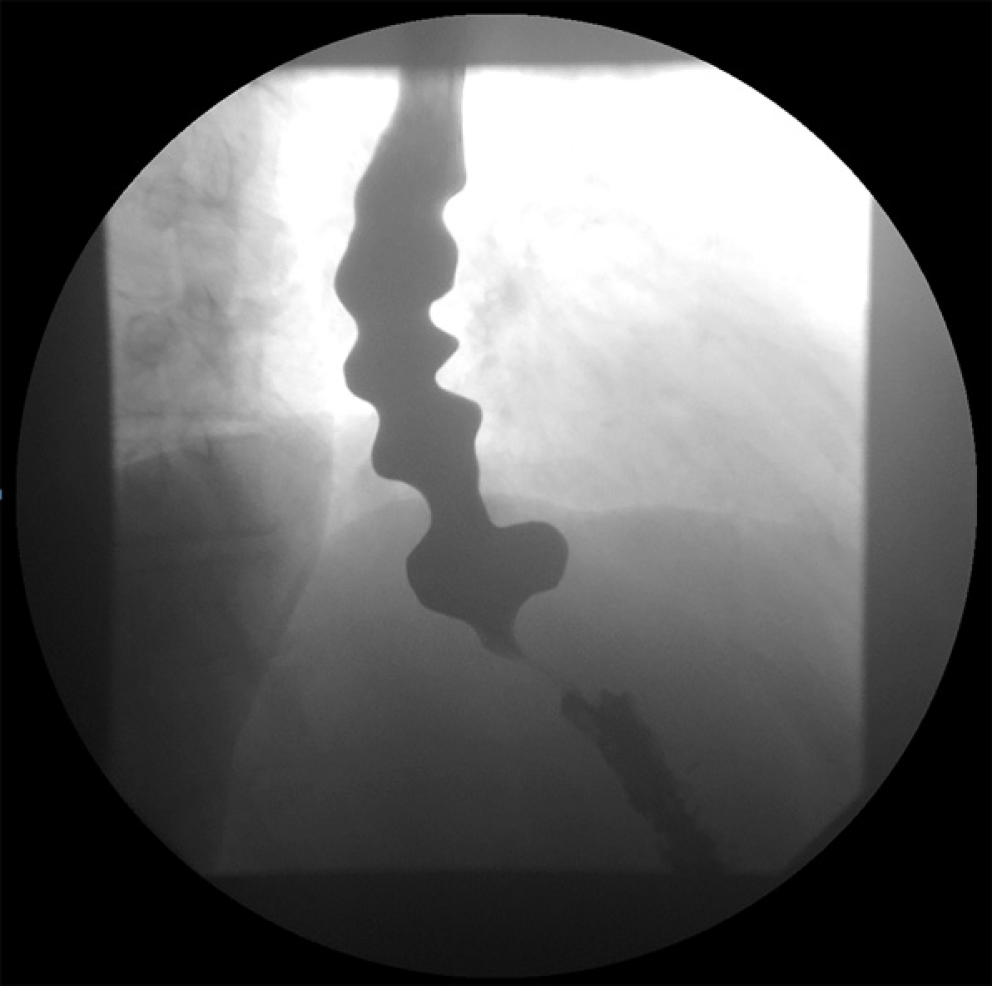

Findings on ancillary tests such as endoscopy and barium esophagram are not specific to DES, but they can provide important clues toward the diagnosis. Endoscopy can reveal spastic, vigorous and/or uncoordinated contractions in the distal esophagus. In addition, mucosal changes related to stasis of foam (saliva) and liquid retention may be observed, suggesting a motility disorder. It is crucial to assess for any sequelae of GERD such as esophagitis and peptic stricture. The EGJ should be carefully evaluated in forward and retroflexed views for the presence of hiatal hernia and tightness of the LES in relation to endoscope diameter. Esophageal mucosal biopsies should be obtained to rule out eosinophilic esophagitis in patients with dysphagia. Barium esophagram may show barium retention and corkscrew configuration (Figure 1). pH monitoring should be considered if GERD is suspected as an etiology.

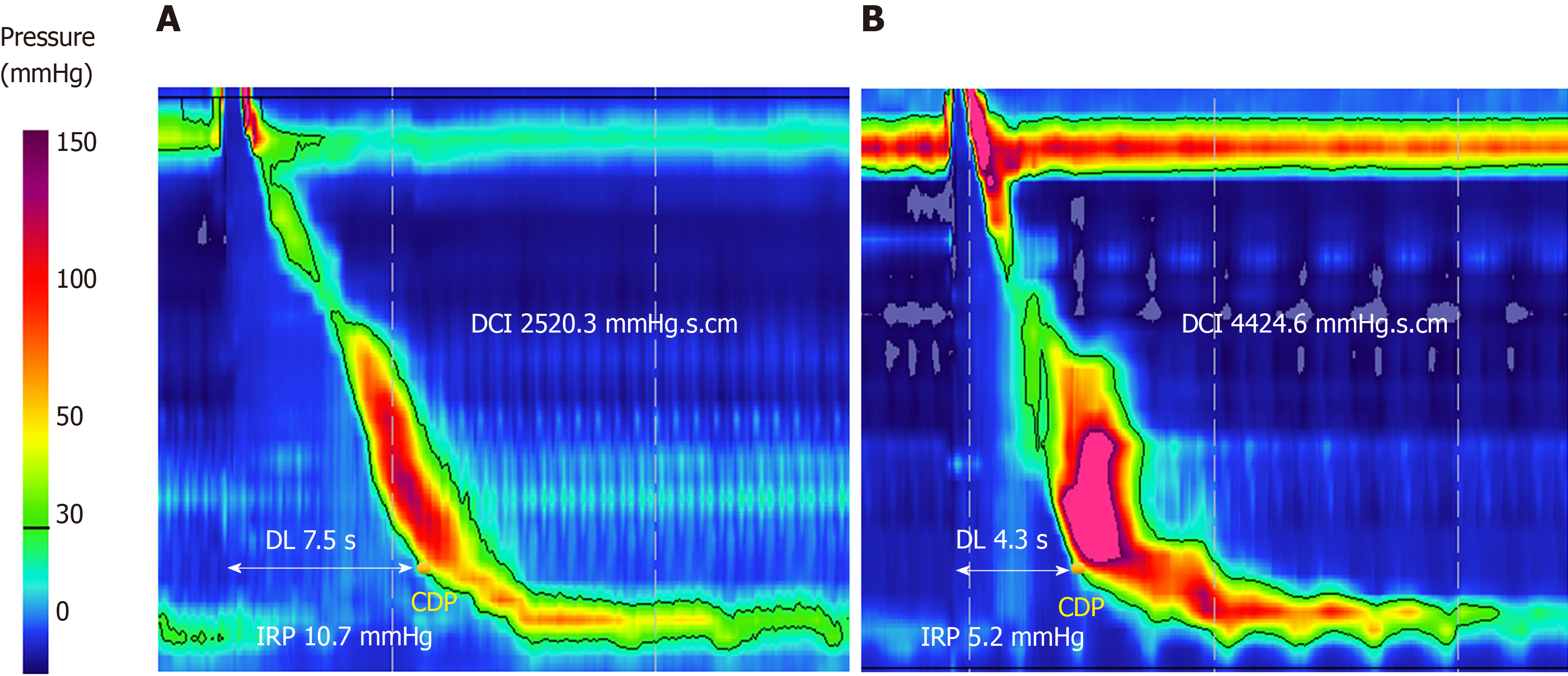

HRM is the gold standard for the diagnosis of DES. The CC v3.0 classifies DES as a major motility disorder and defines DES by findings of premature contractions [distal latency (DL) < 4.5 s] in at least 20% of wet swallows, in conjunction with normal LES relaxation measured by integrated relaxation pressure ≤ 15 mmHg (Figure 2). The cutoff value of 15 mmHg used in the CC v3.0 is based on the Sierra design, currently acquired by Medtronic (Medtronic Inc. Minnesota, United States)[3]. DL, measured from the time of upper esophageal sphincter relaxation to the contractile deceleration point, is a measurement used in esophageal pressure topography to help quantify the integrity of deglutitive inhibitory pathway. The previously used criteria of rapid contractions, defined as contractile front velocity greater than 9 cm/s, to diagnose DES was removed from the CC v3.0 as this was shown to be non-specific and can be seen in normal subjects and in other esophageal motility disorders. In contrast, subjects with reduced DL were found to have either DES or achalasia type III[22]. Of note, 96% of this group had dysphagia as the dominant symptom, signifying a much more homogenous clinical entity. Based on these findings it was determined in CC v3.0 to eliminate rapid contractions with normal latency as an abnormal criterion when interpreting HRM studies[3].

DES and spastic achalasia (achalasia type 3) appear to share a common pathophysiologic pathway. One study performed during the era of conventional manometry found that DES progresses to achalasia in 8% (1/12) of patients after a mean follow up of 4.8 years[23]. Another study that also used conventional manometry found a higher rate of 14% (5/35) after a shorter follow up of 2.1 years[24]. Nonetheless, results of these studies should be interpreted with caution because the diagnosis of achalasia can be missed using conventional manometry. The phenomenon of “pseudo-relaxation” may result from esophageal shortening during swallowing, and the actual LES to move upward along the catheter, leading the distal pressure sensor to measure the intragastric pressure rather than the actual LES pressure. In addition, simultaneous contractions may correspond to panesophageal pressurization, a finding that can be missed on conventional manometry but can be easily identified on HRM[22,25]. Therefore, the incidence of DES was likely overestimated using conventional manometry as some cases of achalasia may have been erroneously diagnosed as DES. However, there have been case reports of DES progressing to achalasia using HRM[26,27].

Another relatively new technologic tool is the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP) which is increasingly being utilized as an additional diagnostic instrument in evaluating esophageal disorders. By using a volume-distension balloon placed across the EGJ, this technology assesses EGJ opening dynamics and distensibility, and evaluates secondary peristalsis that results from the balloon placement in the distal esophagus[28,29]. FLIP can identify EGJOO in the setting of spastic disorders with normal integrated relaxation pressure on HRM (e.g., jackhammer esophagus), which raises the suspicion that spastic disorders like jackhammer esophagus and DES are oftentimes associated with EGJOO that is not captured by HRM. FLIP can have a major role in such cases and can alter the course of management. Further research is needed to clarify and optimize the role of FLIP in these patients.

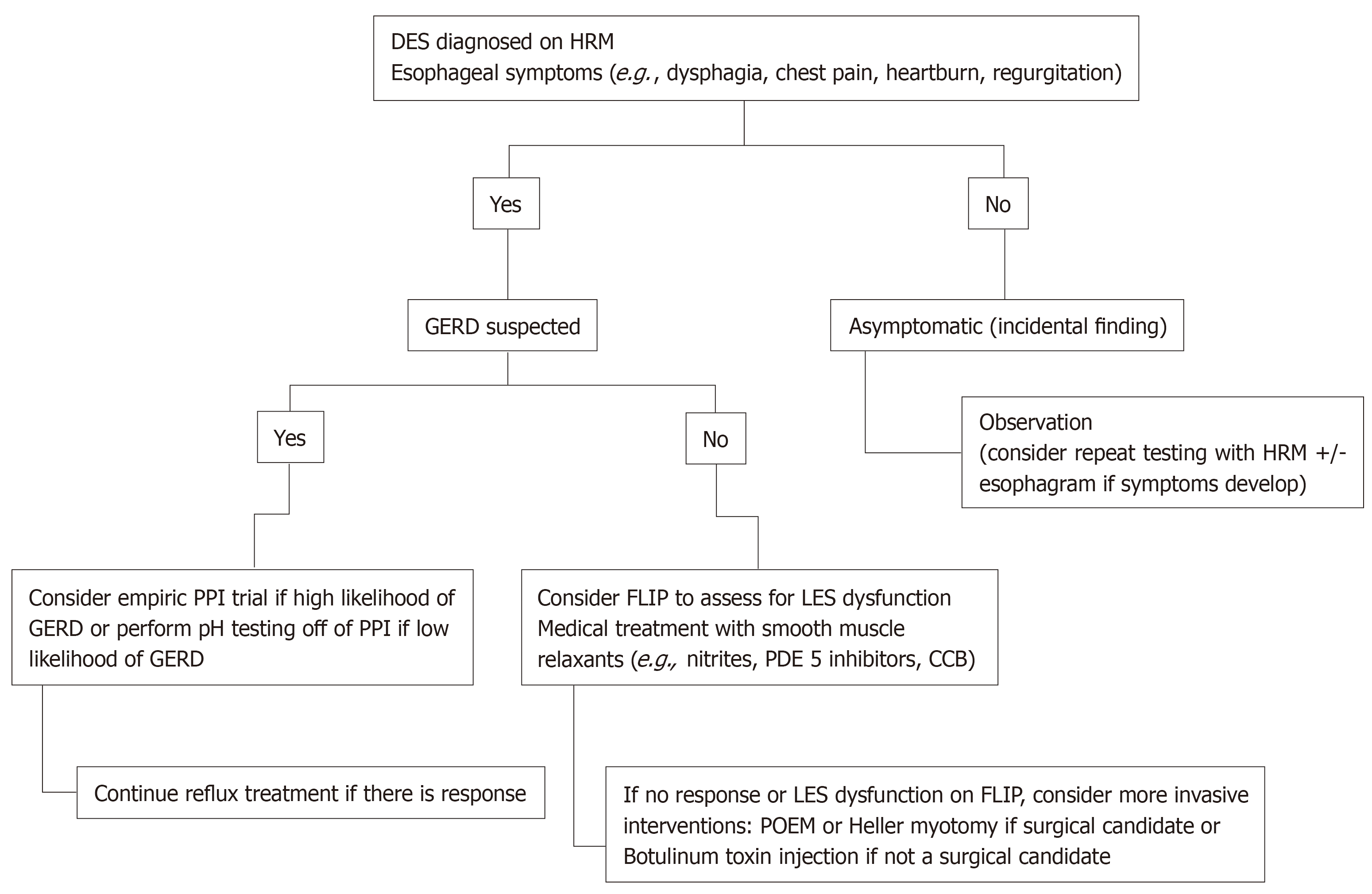

Treatment of DES is challenging because of the heterogeneity in its presentation. Figure 3 represents a proposed algorithm for management of DES. Given that esophageal spasm can be seen in the setting of GERD[12], testing for reflux and empiric treatment with antisecretory agents such as proton pump inhibitors should be considered. Since NO is postulated to play a major role in the pathogenesis of DES, medications that enhance NO level can be attempted. Both nitrites and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors are considered to decrease symptoms by increasing the availability of NO, allowing for increased relaxation and decreased contractions[30,31]. Case reports and trials have noted a decrease in LES pressure and peristaltic contraction amplitude, as well as symptom resolution (specifically dysphagia in esophageal motility disorder) with the use of sildenafil[32]. Calcium channel blockers work by inhibiting L-type channels, leading to relaxation of the smooth muscle[32]. These agents have also been used with limited success[33]. Other pharmacological treatment include tricyclic anti-depressants and serotonin-reuptake inhibitor[30]. Pharmacologic therapy should be considered first before considering more invasive interventions. However, it has a limited efficacy and testing in clinical trials is limited[21,30].

In cases with persistent symptoms despite medical therapy, endoscopic treatment interventions with botulinum toxin injection and Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) should be considered. Botulinum toxin works by inhibiting the release of acetylcholine in the neuromuscular junction, leading to muscle paralysis. It has been shown to reduce dysphagia score, stabilization of unintentional weight loss, and decrease LES pressure in patients with spastic esophageal disorders[34]. Although botulinum injection is generally safe and adds a little time to endoscopic procedures, it is important to note that its efficacy is limited to less than a year usually. Chest pain may occur after the procedure and rare side effects such as mediastinitis or allergic reaction to egg protein component of the injection have been reported. Additionally, botulinum injection may make future esophageal myotomy challenging, especially with repeated use[35]. Pneumatic dilation has been proposed as a management strategy for DES but has had minimal success[36-38].

Although POEM has largely been studied for achalasia, it has been explored in the recent years as a treatment modality for non-achalasia spastic esophageal motility disorders including DES. POEM seems to be effective (success rate > 80%) and safe for spastic disorders with infrequent significant adverse events when performed by experienced endoscopists[36-38]. However, these studies are retrospective and randomized controlled trials are needed to further assess the role of POEM in non-achalasia spastic esophageal motility disorders[36-38]. POEM for DES appears to require longer procedure time as compared to achalasia due to spastic contractions complicating the procedure execution. Also, a lack of widespread equipment availability coupled with few expert proceduralists leads to limited access to this treatment resource. Despite these disadvantages, POEM continues to be a promising mode of treatment for DES. Surgical myotomy is another option for DES when medical therapy fails and expertise to perform POEM is not available[39]. However, extended myotomy beyond mid esophagus is difficult and may not be as feasible when compared to POEM.

While the prevailing symptoms of DES are dysphagia and chest pain, its clinical presentation can be diverse including heartburn, nausea, vomiting and weight loss. HRM is the gold standard for diagnosis, and additional testing with FLIP should be considered, as EGJOO may not be clearly apparent on HRM, especially that DES shares a common pathophysiologic pathway with spastic achalasia and may progress to achalasia overtime. Due to an unknown etiology of DES, most pharmacological medications are aimed at treating the symptoms with limited success rates. Future studies clarifying this entity could aid in better understanding of the pathophysiology of DES, leading to more effective treatment options. POEM appears to be a promising option when expertise is available; and botulinum toxin injection is a temporary therapeutic option, especially in high risk surgical patients.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiu KW, Wang D, Sato H S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Osgood H. A peculiar form of esophagismus. Boston Med Surg J. 1889;120:401-403. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moersch JJ, Camp JD. Diffuse spasm of the lower part of the esophagus. Ann Otol. 1934;43:1165-1173. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE; International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1373] [Cited by in RCA: 1450] [Article Influence: 145.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Richter JE, Castell DO. Diffuse esophageal spasm: a reappraisal. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:242-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Roth HP, Fleshler B. Diffuse Esophageal Spasm; Clinical, Radiological, And Manometric Observations. Ann Intern Med. 1964;61:914-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Creamer B, Donoghue E, Code CF. Pattern of esophageal motility in diffuse spasm. Gastroenterology. 1958;34:782-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carlson DA, Pandolfino JE. High-Resolution Manometry in Clinical Practice. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11:374-384. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Murray JA, Ledlow A, Launspach J, Evans D, Loveday M, Conklin JL. The effects of recombinant human hemoglobin on esophageal motor functions in humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1241-1248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roman S, Kahrilas PJ. Management of spastic disorders of the esophagus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:27-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Goyal RK, Chaudhury A. Physiology of normal esophageal motility. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:610-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Behar J, Biancani P. Pathogenesis of simultaneous esophageal contractions in patients with motility disorders. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:111-118. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Crespin OM, Tatum RP, Yates RB, Sahin M, Coskun K, Martin AV, Wright A, Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA. Esophageal hypermotility: cause or effect? Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:497-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Clouse RE. Psychiatric disorders in patients with esophageal disease. Med Clin North Am. 1991;75:1081-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Almansa C, Heckman MG, DeVault KR, Bouras E, Achem SR. Esophageal spasm: demographic, clinical, radiographic, and manometric features in 108 patients. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:214-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | He YQ, Sheng JQ, Wang JH, An HJ, Wang X, Li AQ, Wang XW, Gyawali CP. Symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm as a major ictal manifestation of post-traumatic epilepsy: a case report. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ratuapli SK, Crowell MD, DiBaise JK, Vela MF, Ramirez FC, Burdick GE, Lacy BE, Murray JA. Opioid-Induced Esophageal Dysfunction (OIED) in Patients on Chronic Opioids. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:979-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Snyder DL, Crowell MD, Horsley-Silva J, Ravi K, Lacy BE, Vela MF. Opioid-Induced Esophageal Dysfunction: Differential Effects of Type and Dose. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1464-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patel D, Callaway J, Vaezi M. Opioid-Induced Foregut Dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:1716-1725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nakajima N, Sato H, Takahashi K, Hasegawa G, Mizuno K, Hashimoto S, Sato Y, Terai S. Muscle layer histopathology and manometry pattern of primary esophageal motility disorders including achalasia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Henderson RD, Ryder D, Marryatt G. Extended esophageal myotomy and short total fundoplication hernia repair in diffuse esophageal spasm: five-year review in 34 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;43:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Roman S, Kahrilas PJ. Distal esophageal spasm. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:328-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Carlson D, Luger D, Bidari K, Boris L, Kwiatek MA, Kahrilas PJ. Distal esophageal spasm in high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: defining clinical phenotypes. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:469-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khatami SS, Khandwala F, Shay SS, Vaezi MF. Does diffuse esophageal spasm progress to achalasia? A prospective cohort study. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1605-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fontes LH, Herbella FA, Rodriguez TN, Trivino T, Farah JF. Progression of diffuse esophageal spasm to achalasia: incidence and predictive factors. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:470-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Rice J, Clarke JO, Kwiatek M, Kahrilas PJ. Impaired deglutitive EGJ relaxation in clinical esophageal manometry: a quantitative analysis of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G878-G885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Samo S, Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Ineffective Esophageal Motility Progressing into Distal Esophageal Spasm and Then Type III Achalasia. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | De Schepper HU, Smout AJ, Bredenoord AJ. Distal esophageal spasm evolving to achalasia in high resolution. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:A25-A26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Lin Z, Hirano I, Gonsalves N, Listernick Z, Ritter K, Tye M, Ponds FA, Wong I, Pandolfino JE. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1726-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hirano I, Pandolfino JE, Boeckxstaens GE. Functional Lumen Imaging Probe for the Management of Esophageal Disorders: Expert Review From the Clinical Practice Updates Committee of the AGA Institute. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:325-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Miller DR, Averbukh LD, Kwon SY, Farrell J, Bhargava S, Horrigan J, Tadros M. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors are viable options for treating esophageal motility disorders: A case report and literature review. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:495-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fox M, Sweis R, Wong T, Anggiansah A. Sildenafil relieves symptoms and normalizes motility in patients with oesophageal spasm: a report of two cases. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:798-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Khalaf M, Chowdhary S, Elias PS, Castell D. Distal Esophageal Spasm: A Review. Am J Med. 2018;131:1034-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim HM, Lee TH. Interesting Findings of High-resolution Manometry Before and After Treatment in a Case of Diffuse Esophageal Spasm. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:107-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Vanuytsel T, Bisschops R, Farré R, Pauwels A, Holvoet L, Arts J, Caenepeel P, De Wulf D, Mimidis K, Rommel N, Tack J. Botulinum toxin reduces Dysphagia in patients with nonachalasia primary esophageal motility disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1115-1121.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Smith CD, Stival A, Howell DL, Swafford V. Endoscopic therapy for achalasia before Heller myotomy results in worse outcomes than heller myotomy alone. Ann Surg. 2006;243:579-584; discussion 584-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Khan MA, Kumbhari V, Ngamruengphong S, Ismail A, Chen YI, Chavez YH, Bukhari M, Nollan R, Ismail MK, Onimaru M, Balassone V, Sharata A, Swanstrom L, Inoue H, Repici A, Khashab MA. Is POEM the Answer for Management of Spastic Esophageal Disorders? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Khashab MA, Familiari P, Draganov PV, Aridi HD, Cho JY, Ujiki M, Rio Tinto R, Louis H, Desai PN, Velanovich V, Albéniz E, Haji A, Marks J, Costamagna G, Devière J, Perbtani Y, Hedberg M, Estremera F, Martin Del Campo LA, Yang D, Bukhari M, Brewer O, Sanaei O, Fayad L, Agarwal A, Kumbhari V, Chen YI. Peroral endoscopic myotomy is effective and safe in non-achalasia esophageal motility disorders: an international multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E1031-E1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Khashab MA, Messallam AA, Onimaru M, Teitelbaum EN, Ujiki MB, Gitelis ME, Modayil RJ, Hungness ES, Stavropoulos SN, El Zein MH, Shiwaku H, Kunda R, Repici A, Minami H, Chiu PW, Ponsky J, Kumbhari V, Saxena P, Maydeo AP, Inoue H. International multicenter experience with peroral endoscopic myotomy for the treatment of spastic esophageal disorders refractory to medical therapy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1170-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Almansa C, Hinder RA, Smith CD, Achem SR. A comprehensive appraisal of the surgical treatment of diffuse esophageal spasm. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1133-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |