Published online Dec 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6071

Peer-review started: May 28, 2020

First decision: September 24, 2020

Revised: October 11, 2020

Accepted: October 26, 2020

Article in press: October 26, 2020

Published online: December 6, 2020

Processing time: 189 Days and 18.7 Hours

Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) is a distinct clinicopathologic entity characterized by the infiltration of the bone marrow by clonal lymphoplasmacytic cells that produce monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) in the blood, and patients may present with symptoms related to the infiltration of the hematopoietic tissues or the effects of monoclonal IgM in the blood. Funduscopic abnormalities were noted in some of the patients due to hyperviscosity or other retinal lesions. Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) as a non-invasive imaging tool can give qualitative and quantitative information about the status of retinal and choroidal vessels, which might be useful for diagnosing patients with WM-associated retinopathy.

The patient was a 67-year-old man who presented with sudden visual disturbance in both eyes. Ophthalmic tests showed that best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) for this patient was 20/100 in the right eye and 20/1000 in the left eye. Fundus examination, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and OCTA revealed substantial bilateral optic disc edema, dilated and tortuous retinal veins, and diffuse intraretinal blot hemorrhages and edema which were consistent with bilateral central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). Meanwhile, remarkable bilateral serous macular detachments (SMD) were noticed on OCT. Systemic examinations showed that the patient had anemia and extremely high level of monoclonal IgM and infiltration of clonal lymphoplasmacytic cells in bone marrow. The diagnosis of WM with hyperviscosity and retinopathy was made based on the clinical manifestation and laboratory findings. He was subsequently treated with intravitreal ranibizumab injection, plasmapheresis, and bortezomib plus rituximab with dexamethasone. Six months after treatments, the central macular volume decreased by 16.1% in the right eye and 28.6% in the left eye on OCT, and the patient’s BCVA was improved to 20/60 in the right eye and 20/400 in the left eye. Very good partial response was obtained after systemic treatment.

WM may affect visual function and present as bilateral CRVO. OCTA can show characteristic changes in both retina and choroid vasculatures, which might be of great value for diagnosing or following patients with WM retinopathy. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment combined with systemic therapy might be beneficial for WM patients with retinopathy (SMD and CRVO).

Core Tip: Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma with immunoglobulin M monoclonal protein, which can be associated with impressive hyperviscosity retinopathy and a unique tendency to develop serous macular detachments. Optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) is a new, non-invasive imaging system, providing both structural and blood flow information in the eye. This technique might be of great value for diagnosing or following patients with retinal vascular diseases such as WM retinopathy, especially for those who could not be performed for fluorescein angiography. Here, we report a case of WM retinopathy in both eyes who was treated with intravitreal ranibizumab injection combined with systemic plasmapheresis and chemotherapy. Also, we describe the defining OCTA features associated with WM which have not been reported before.

- Citation: Li J, Zhang R, Gu F, Liu ZL, Sun P. Optical coherence tomography angiography characteristics in Waldenström macroglobulinemia retinopathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(23): 6071-6079

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i23/6071.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6071

Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) is a lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma characterized by the presence of monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody[1]. Because of its relatively large molecular structure with a bulky pentamer form of 970 kDa, 70%-95% of IgM is confined to the intravascular compartment, leading to hyperviscosity syndrome[2]. Other clinical manifestations include anemia, thrombocytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and the presence of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the bone marrow[3]. Patients with WM are at a higher risk of developing hyperviscosity retinopathy. Two main manifestations are serous macular detachment (SMD, also known as immunogammopathy maculopathy) and central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) with typical fundus findings of optic disc oedema, intraretinal hemorrhage and oedema, and dilated and tortuous retinal veins[4-8]. The retinopathy is usually persistent even after significant reduction of IgM levels via routine systemic plasmapheresis treatment and chemotherapy. Ocular interventions such as intravitreal triamcinolone and intravitreal dexamethasone implantation have resulted in slight reductions of SMD but no improvement in visual acuity[7]. Treatments of WM retinopathy with intravitreal bevacizumab have reportedly achieved partial macular oedema resolution, subretinal fluid absorption, and vision improvement (Table 1), suggesting that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may be involved in WM[7-10].

| Ref. | Number of cases | Systemic treatment | Local treatment | Outcome |

| Fenicia et al[7], 2013 | 1 | None | One intravitreal injection of dexamethasone | Progressive slight reduction of SMD but no improvement of visual acuity |

| Besirli et al[8], 2013 | 1 | Plasmapheresis and systemic chemotherapy | Intravitreal injections of bevacizumab, panretinal photocoagulation and intravitreal corticosteroid | Improvement of hyperviscosity retinopathy, unsuccessful in reversing the maculopathy |

| Kapoor | 1 | Chemotherapy, plasmapheresis | Intravitreal bevacizumab | Complete resolution of intraretinal hemorrhages, complete resolution of all subretinal fluid |

| Ratanam et al[10], 2015 | 1 | Plasmapheresis | Repeated intravitreal bevacizumab | Reduced macular edema |

Herein we describe a case wherein intravitreal ranibizumab injection was used to treat the patient with SMD and CRVO secondary to WM, and discuss the optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography (OCTA) features of this retinopathy.

A 67-year-old man came to our clinic in May 2018 due to sudden visual disturbance in both eyes.

The patient had sudden visual disturbance in both eyes. The patient had a 1-year history of nasal and gingival bleeding without paying any attention.

His previous history included hypertension for 10 years. He had no history of ocular diseases.

The best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/100 in the right eye and 20/1000 in the left eye. Intraocular pressures of both eyes were normal. Anterior segment examination only showed pallor of the conjunctiva. Fundus examination revealed substantial bilateral optic disc oedema, severe macular oedema, dilated and tortuous retinal veins, and diffuse intraretinal blot hemorrhages and oedema (Figure 1). The systemic physical examination did not reveal any abnormalities.

The patient was also referred to a hematologist due to a history of nasal and gingival bleeding and systemic workup was performed. Blood tests revealed anemia [hemoglobin (HGB), 77 g/L] and elevated IgM (122.6 g/L). Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) pattern showed a monoclonal (M) protein in the gamma region (63.9%). Immunofixation (IFE) showed that the M protein is IgM kappa. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy findings showed infiltration by small lymphoid and plasmacytoid cells (Figure 2A and B), which were confirmed as clonal mature B cells by flow cytometry (Figure 2C; P3 group 8.3%, mainly expressed CD19, CD20, CD22, CXCR4, and HLA-DR and partially expressed cKappa, but did not express other markers). Karyotyping analysis of bone marrow sample suggested 46,XY. The patient had slight enlargement of the spleen (12.2 cm × 4.5 cm) by ultrasound and mediastinal lymph node enlargement by chest high-resolution computed tomography.

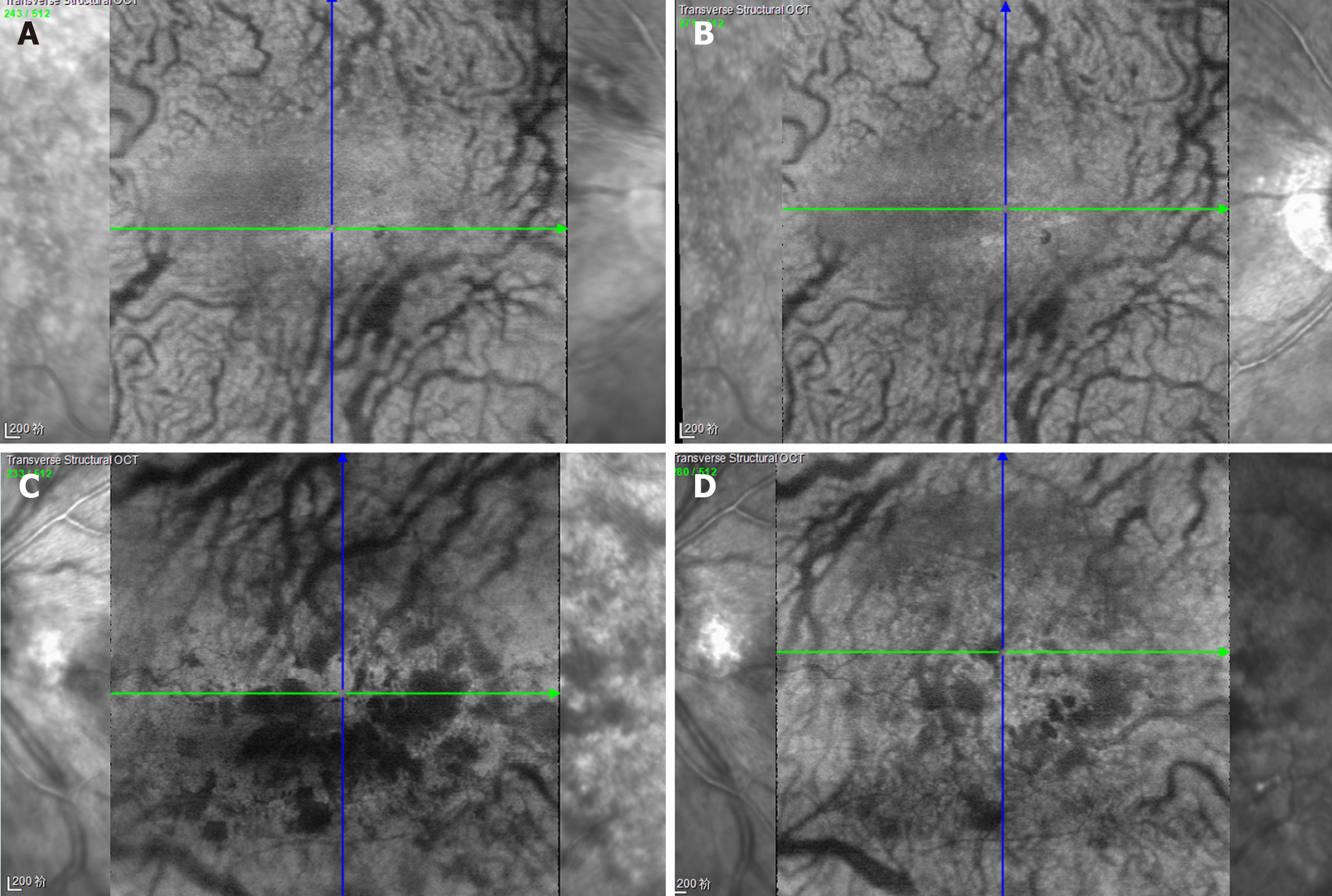

OCT depicted intraretinal oedema with massive sub-macular fluid in both eyes (Figure 3A and B). The patient did not undergo fundus fluorescein angiography due to allergy to fluorescein sodium. OCTA depicted blurred capillary networks, petaloid cysts in the outer plexiform layer, and augmented choroidal large blood vessels (Figures 4A, 4B, 4G, 5A and 5C). The imaging changes were consistent with bilateral CRVO and SMD.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with WM with hyperviscosity and WM retinopathy based on the clinical manifestation and laboratory findings.

The patient underwent once bilateral intravitreal ranibizumab injection (0.05 mL, 0.5 mg), then was admitted to the Department of Hematology for systemic treatment. The patient was treated with plasmapheresis at the beginning, and subsequently with chemotherapy including one cycle of dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab and four cycles of bortezomib plus rituximab with dexamethasone. The last treatment occurred in November 2018.

For the ophthalmologic examination, at the 4-wk follow-up (July 2018), OCT revealed reduction of central retinal thickness and central choroidal thickness consistent with substantial resolution of macular oedema and SMD in both eyes (Figure 3C and D). OCTA revealed resolution of intraretinal oedema and improvement of disrupted vasculature in both the retina and choroid (Figures 4C, 4D, 4H, 5B, and 5D). BCVA increased to 20/80 in the right eye and 20/400 in the left eye. At the 6mo follow-up (November 2018), BCVA was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/400 in the left eye. The intraretinal oedema had almost completely resolved and the subretinal fluid in both eyes had continued to improve, as determined via OCT (Figure 3E and F) and OCTA (Figure 4E and F). Compared to baseline, the central macular volume was reduced by 16.1% (from 10.59 mm3 to 8.89 mm3) in the right eye and by 28.6% (from 18.9 mm3 to 13.5 mm3) in the left eye.

For the systemic evaluation, very good partial response was obtained for this patient. The last follow-up occurred in June 2020. The HGB level and IgM level were back to normal (HGB, 154 g/L; IgM, 3.27 g/L). No M protein was detected by SPEP (> 90% reduction). The size of the spleen was normal and the patient had no obvious symptoms and signs. The serum IgM kappa protein still could be detected by IFE.

WM is a B-cell lymphoma associated with high levels of IgM, characterized by elevated serum viscosity and the presence of lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in multiple organs[11]. The disease is rare with an incidence of three cases per million people per year in the United States. The major risk factors are male gender, Caucasian race, and age over 60 years[12]. By contrast, WM has not been studied extensively in Asia because of the relatively low prevalence. However, comparatively low morbidity and distinct characteristics such as younger age at onset and an increased tendency to progress to advanced stage exist in WM in the Chinese population in comparison to the West[13,14].

Some patients with WM develop hyperviscosity retinopathies such as SMD and CRVO[15]. Numerous aspects pertaining to the pathogenesis of ocular manifestations associated with WM remain unclear. SMD associated with hyperviscosity retinopathy in WM is uncommon, and used to be described as immunogammopathy maculopathy[9]. In most cases, SMD is associated with very slow resolution and a poor visual prognosis despite systemic plasmapheresis treatment and chemotherapy. Therefore, understanding the mechanism, as well as earlier recognition and treatment, might be important for the improvement of the prognosis of SMD. Retinal pigment epithelial atrophy beneath the area corresponding to the serous detachment provides a plausible explanation for the unresponsive nature of this presentation, even related to the visual progress, emphasizing the benefit of early intervention[4]. Baker et al[5] reported discontinuity of the outer layer of the retina depicted in OCT of patients with WM retinopathy, and hypothesized that this change may enable immunoglobulins derived from intraretinal oedema to infiltrate the subretinal space, creating an osmotic gradient and resulting in SMD. Sen et al[16] reported localized IgG and IgM reactivity in the junction between the inner and outer photoreceptor segments detected via indirect immunohistochemistry. Leskov et al[17] did not detect similar features on OCT or angiography, but suggested that disruption of retinal pigment epithelium pumping function caused by hyperglobulinemia may play a main role in the development of SMD. No disruption of the outer limiting membrane underneath the intraretinal oedema was detected in the present case, and submacular fluid persisted even after near complete recovery of sensory retinal oedema. OCT results similar to those associated with central serous chorioretinopathy were obtained, supporting a hypothesis of retinal pigment epithelium pumping dysfunction during the advanced stage.

Spectral domain OCT and OCTA are useful examinations in cases of maculopathy. In the present case, baseline OCT depicted severe serous detachment of the sensory retina in the macular area and intraretinal oedema located in the outer plexiform layer. Although substantial changes in OCTA results were not detected in a previous study[17], three main changes were identified in the present case. One was that the macula oedema presented as petaloid cysts in the outer plexiform layer, and another was that the capillary network of the macula was blurred and irregular. Lastly, choroidal large blood vessels were augmented, but the whole choroidal layer did not exhibit obvious thickening. All these OCTA-determined changes improved after the above-described treatment.

Whether retinopathy present in WM patients should be renamed WM-associated retinopathy or cancer-associated retinopathy rather than CRVO remains controversial[16]. It may be more descriptively accurate to refer to this kind of entity as ‘bilateral CRVO’ in clinical practice because the pathological change is stasis of blood flow that is coincident with CRVO caused by hyperviscosity. It has been reported that bilateral CRVO occurs as a complication in approximately 15% of patients with WM[18], underscoring the necessity for hematological evaluations such as serum protein electrophoresis in patients presenting with bilateral CRVO.

To date there has been still no recognized treatment for WM retinopathy. Blau-Most et al[19] reported achieving partial remission via systemic immunosuppressive therapy alone in a case of WM with bilateral CRVO. In another report, the administration of intravitreal triamcinolone and intravitreal dexamethasone implantation did not result in a satisfactory outcome[7], which suggested that inflammation may not be the main pathogenetic pathway in WM. Intravitreal bevacizumab has reportedly been efficacious in some recent cases, and authors have hypothesized that, similar to CRVO, upregulation of VEGF and interleukin-6 caused by hypoxia and hyperviscosity may be the main pathophysiological changes involved[9]. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors including ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib had been approved for the treatment of WM with high response rates and sustained remissions. Leskov et al[17] once reported that ibrutinib contributed to resolution of the patient's retinopathy with an improvement in vision at a 13-mo follow-up, suggesting that this may be the preferred treatment for WM patients with associated retinopathy.

To the best of our knowledge, the current report is the first description of defining OCTA features of WM maculopathy and treatment of WM retinopathy with intravitreal ranibizumab injection combined with systemic plasmapheresis and chemotherapy. The shortage of this study is relatively short follow-up period and pro re nata treatment strategy of intravitreal injection. Further observation and studies are needed, such as VEGF and interleukin level test of aqueous humor, to clarify the mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of WM retinopathy, and identify optimal treatment strategies.

WM may affect visual function and present as bilateral CRVO and/or SMD. In this case, OCTA showed characteristic changes in both retina and choroid vasculatures. Our data and previous reports indicated that intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment might be an effective strategy for the treatment of WM with retinopathy when combined with systemic therapy, which needs further validation.

We acknowledge Professor Yan XJ who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted in this paper.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Langford M S-Editor: Chen XF L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Johnson SA, Oscier DG, Leblond V. Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia. Blood Rev. 2002;16:175-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dumas G, Merceron S, Zafrani L, Canet E, Lemiale V, Kouatchet A, Azoulay E. [Hyperviscosity syndrome]. Rev Med Interne. 2015;36:588-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gertz MA. Waldenström macroglobulinemia: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:266-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pilon AF, Rhee PS, Messner LV. Bilateral, persistent serous macular detachments with Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:573-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baker PS, Garg SJ, Fineman MS, Chiang A, Alshareef RA, Belmont J, Brown GC. Serous macular detachment in Waldenström macroglobulinemia: a report of four cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155:448-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quhill F, Khan I, Rashid A. Bilateral serous macular detachments in Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fenicia V, Balestrieri M, Perdicchi A, Maraone G, Recupero SM. Intravitreal Injection of Dexamethasone Implant in Serous Macular Detachment Associated with Waldenström's Disease. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Besirli CG, Johnson MW. Immunogammopathy maculopathy associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia is refractory to conventional interventions for macular edema. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2013;7:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kapoor KG, Wagner MS. Bevacizumab in macular serous detachments associated with Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2015;46:95-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ratanam M, Ngim YS, Khalidin N, Subrayan V. Intravitreal bevacizumab: a viable treatment for bilateral central retinal vein occlusion with serous macular detachment secondary to Waldenström macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;170:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dimopoulos MA, Panayiotidis P, Moulopoulos LA, Sfikakis P, Dalakas M. Waldenström's macroglobulinemia: clinical features, complications, and management. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:214-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gertz MA. Waldenström macroglobulinemia: 2015 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:346-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu Y, Chen SL, Zhong YP, Li X, An N, Zhang JJ. [Clinical analysis of 15 patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2009;48:193-195. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yi S, Cui R, Li Z, An G, Qi J, Zou D, Zhang P, Chen H, Wang J, Chang H, Qiu L. Distinct characteristics and new prognostic scoring system for Chinese patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Chin Med J. 127:2327-2331. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dimopoulos MA, Kyle RA, Anagnostopoulos A, Treon SP. Diagnosis and management of Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1564-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sen HN, Chan CC, Caruso RC, Fariss RN, Nussenblatt RB, Buggage RR. Waldenström's macroglobulinemia-associated retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:535-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leskov I, Knezevic A, Gill MK. Serous macular detachment associated with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia managed with ibrutinib: A case report and new insights into pathogenesis. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2018;Online ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gertz MA, Kyle RA. Hyperviscosity syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 1995;10:128-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Blau-Most M, Gepstein R, Rubowitz A. Bilateral simultaneous central retinal vein occlusion in hyperviscosity retinopathy treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy only. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2018;12:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |