Published online Dec 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6016

Peer-review started: May 12, 2020

First decision: September 14, 2020

Revised: September 22, 2020

Accepted: October 12, 2020

Article in press: October 12, 2020

Published online: December 6, 2020

Processing time: 206 Days and 1.1 Hours

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a newly discovered coronavirus that has generated a worldwide outbreak of infections. Many people with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) have developed severe illness, and a significant number have died. However, little is known regarding infection by the novel virus in pregnant women. We herein present a case of COVID-19 confirmed in a woman delivering a neonate who was negative for SARS-CoV-2 and related it to a review of the literature on pregnant women and human coronavirus infections.

The patient was a 36-year-old pregnant woman in her third trimester who had developed progressive clinical symptoms when she was confirmed as infected with SARS-CoV-2. Given the potential risks for both the pregnant woman and the fetus, an emergency cesarean section was performed, and the baby and his mother were separately quarantined and cared for. As a result, the baby currently shows no signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection (his lower respiratory tract samples were negative for the virus), while the mother completely recovered from COVID-19.

Although we presented a single case, the successful result is of great significance for pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection and with respect to fully understanding novel coronavirus pneumonia.

Core Tip: We achieved successful outcomes for both the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infected mother and the neonate. Even though this is a single successful case, the identification, diagnosis, clinical course, and management are of significance for understanding the clinical manifestation, transmission, and related risks among special populations due to the ongoing outbreak of coronavirus disease-2019 pneumonia.

- Citation: Wang RY, Zheng KQ, Xu BZ, Zhang W, Si JG, Xu CY, Chen H, Xu ZY, Wu XM. Healthy neonate born to a SARS-CoV-2 infected woman: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(23): 6016-6025

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i23/6016.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i23.6016

Since the first reports of pneumonia cases caused by a new coronavirus were confirmed in Wuhan, China in December 2019[1] the disease has erupted and proliferated across China and around the world as a pandemic in a relatively short time[2].

The pathogen isolated from clinical samples during this outbreak was a new species of coronavirus similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[3], and it is now officially labeled SARS-CoV-2[4]. It is known that this novel coronavirus can infect various animals and humans[3,5,6], and most individuals exhibit mild, self-limited, upper respiratory tract syndromes. Similar to two members of this viral family-SARS[7] and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)[8], the novel coronavirus can cause fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Some serious cases manifested severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiac injury, and even life-threatening outcomes[1,9-11].

Given that most coronaviruses have zoonotic origins, SARS-CoV-2 is most likely derived from wild animals, and common cross-species infections and periodic spillover events may explain the sporadic emergence in humans. Epidemiologic data indicate that spreading of the new coronavirus among the human population is primarily through respiratory tract droplets as well as close contact[9,12]. It is unknown whether aerosols and the digestive tract are two other paths of transmission. The incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to be between 3 d and 7 d[13].

Early observations suggested that the new mutant virus could infect individuals of all ages, with the elderly and individuals with chronic diseases developing serious conditions and even dying[3,9]. Therefore, it is imperative that certain groups, such as pregnant women and those with underlying risks, be given greater attention. Previous studies have reported that pregnancy in women infected by the other two coronavirus, SARS and MERS, was associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes[14-26]. Therefore, we wished to investigate whether the same situation existed for SARS-CoV-2.

Herein, we present the clinical course of the first cohort of live births from pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 at 36 wk of gestation in Wenzhou, China. This report specifically describes the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, clinical process, and neonatal outcomes of the first case of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy confirmed in China.

A 36-year-old pregnant woman (G3P1) at 34 4/7 wk of gestation returned to Wenzhou from Wuhan on January 20, 2020. Due to her residence history in Wuhan, she was asked to self-quarantine at home. She revealed that she had run a business in Hubei Province, but said that she had not visited the Huanan Seafood wholesale market in Wuhan, which is where most experts believe the coronavirus infected humans.

On January 30, 2020, 9 d after returning to Wenzhou, the woman at 36 wk of pregnancy was hospitalized in the Yueqing People’s Hospital because of the emergence of a dry cough and fever.

No history of past illness.

No personal and family history.

The patient did not exhibit chest pain, shortness of breath, or coarse rales in either lung. Physical examination was as follows: a temperature of 38.5 °C, a pulse rate of 104 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and a blood pressure of 101/76 mm of Hg.

Laboratory examination showed low lymphocyte counts and elevated concentrations of C-reactive protein (Table 1).

| Measure | Reference range | Patient |

| White blood cell count (per microliter) | 4000-10000 | 8130 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (per microliter) | 800-4500 | 510 |

| Proportion of neutrophils (%) | 50.0-70.0 | 90.7 |

| Proportion of lymphocytes (%) | 20.0-45.0 | 6.3 |

| Random glucose (mmol/L) | 4.40-6.70 | 11.55 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.60-1.70 | 2.73 |

| Fibrinogen concentration (g/L) | 2.00-4.00 | 6.24 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) | 28.0-43.5 | 46.0 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0-0.5 | 0.5 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 0-5.0 | 80.2 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 30-162 | 113 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 0-55 | 30 |

| D-dimer (mg/liter) | 0-0.5 | 1.2 |

| Analysis of blood gas | ||

| PCO2 | 35.0-45.0 | 27.1 |

| pH | 7.35-7.45 | 7.41 |

| PO2 | 80.0-100.0 | 91.2 |

| BE | ± 3 | -6 |

| Toxoplasma antibody IgG | Positive | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae antibody IgG (AU/mL) | 0-36.0 | 86.6 |

| Rubella antibody IgG | Positive | |

| Toxoplasma antibody IgG | Positive |

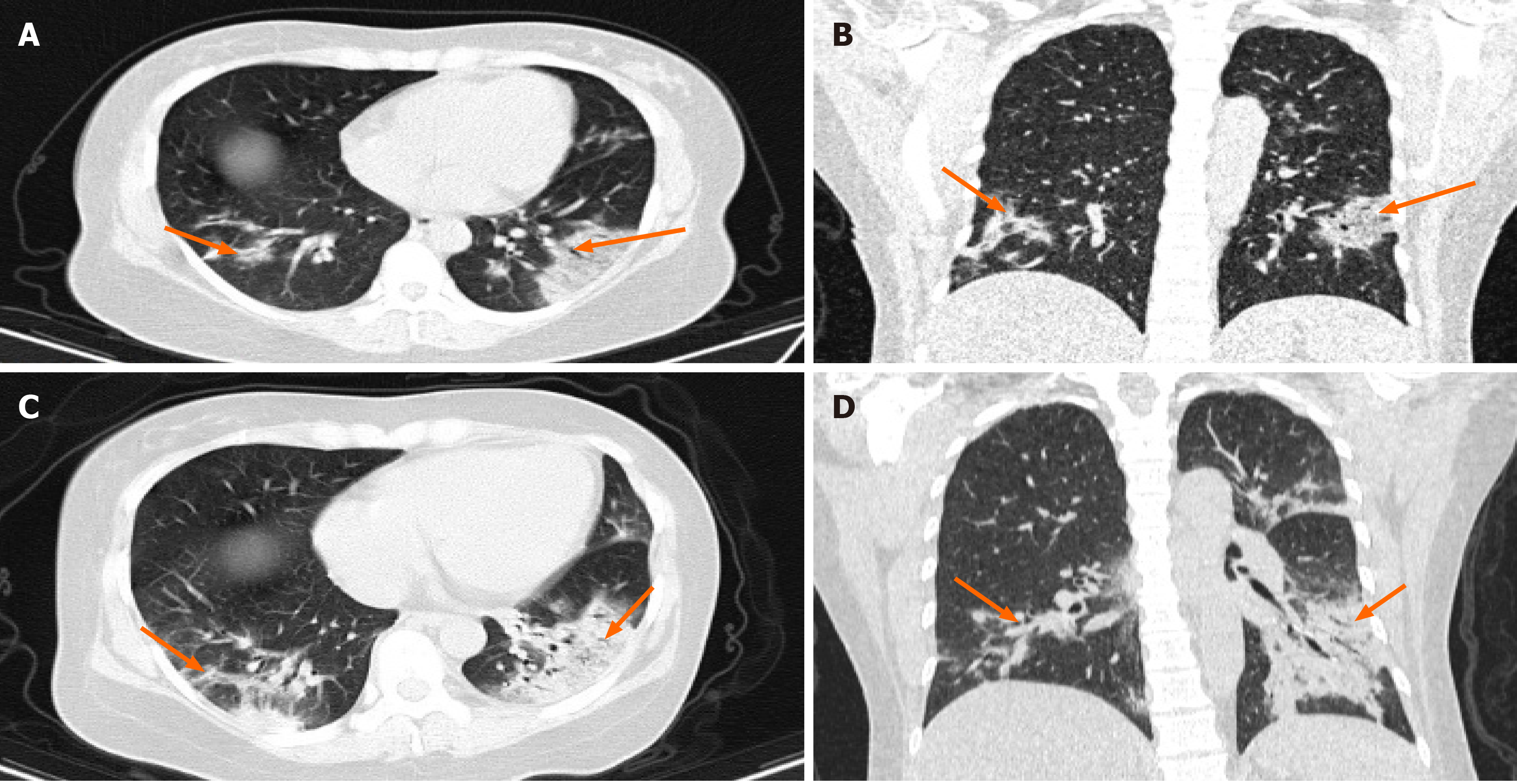

Computed tomography (CT) examination indicated that both lungs possessed multiple patchy, ground-glass-like fuzzy shadows that were primarily distributed under the pleurae (multifocal ground-glass opacities bilaterally, especially in the apical posterior segment of the left-upper lobe) (Figure 1A and 1B).

In view of her residence in Hubei Province, SARS-CoV-2 infection was suspected. The differential diagnosis excluded the likelihood of influenza A, influenza B, respiratory syncytial virus, or adenovirus infections. SARS-CoV-2 was ultimately confirmed in oropharyngeal swab samples taken from the pregnant woman.

Given the unknown risks for SARS-CoV-2 infection of the fetus (and with the fetus approaching full term), an emergency cesarean section was performed on January 31, 2020. The delivered male neonate weighed 2500 g with Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at 1 min and 5 min, respectively. After delivery, the baby and his mother were managed and cared for separately.

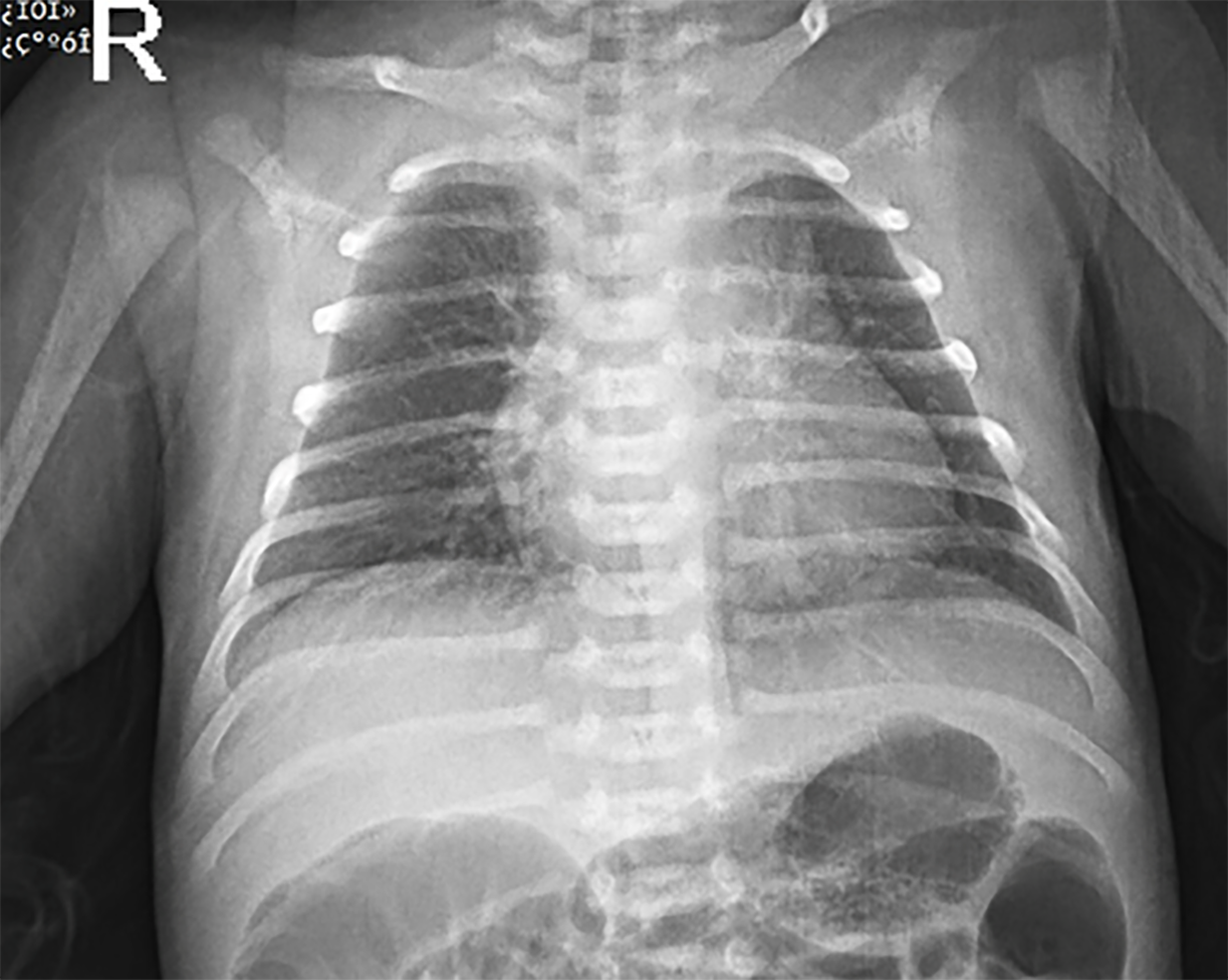

Chest X-ray of the neonate showed no abnormalities (Figure 2). Lower respiratory tract samples from the newborn were collected on February 2, 4, and 6 of 2020; all of the three tests were negative for SARS-CoV-2. A CT scan on the second day after cesarean section showed progressive ground-glass opacities in both lungs of the mother (Figure 1C and 1D). On February 6, 2020, the woman was positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by oropharyngeal samples. Although they were negative on February 23, 2020, the patient remained in hospital isolation. However, she was afebrile and showed stable vital signs.

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that was first identified in late December of 2019 in Wuhan, China[1]. SARS-CoV-2 infections have now resulted in a worldwide pandemic and global public health emergency[2]. The virus generally infects people of all ages, which includes the pregnant population. The most important questions regarding pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection are whether the virus adversely affects subsequent maternal health and perinatal developmental processes.

We know of only two publications on pregnant groups with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The newborns from the first study were negative for SARS-CoV-2, but showed adverse neonatal outcomes[27], and the other study reported a neonate confirmed with coronavirus disease-2019 who possessed mild symptoms and showed a favorable prognosis[28].

As a newly discovered virus, there are not enough data currently available on SARS-CoV-2 causing disease in pregnant individuals. However, we can draw lessons from the pathogenesis observed in pregnant women, which can be attributed to the other members of the coronavirus family. Seven human coronaviruses (HCoVs) have been identified, including two α-CoV members (HCoV-229E and HCoVNL63) and five β-CoV members (HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and now SARS-CoV-2)[1,29].

With PubMed as our primary search database, we examined the literature for the other six HCoVs (HCoV-229E, HCoVNL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV) with respect to infections in pregnant women and found 17 publications from 1989 to February 25, 2020 relating to the topic (we assume that some of the same patients were likely involved in more than 1 article). Nevertheless, as summarized in Table 2, 26 SARS-CoV-infected patients from six publications demonstrated that SARS coronavirus infection was associated with severe maternal conditions, maternal death, spontaneous abortion, and preterm deliveries[13,15-18]. Similarly, a cohort study from Hong Kong revealed that the clinical outcomes among pregnant women with SARS-CoV infection were worse than in infected women who were not pregnant[21].

| Ref. | SS | Nationality | GAAI (wk) | ICUA | Maternal comorbid conditions | Maternal outcome | Fetal outcome | Delivery details | Journal |

| Wong et al[14], 2004 | 12 | Hong Kong | First trimester 7; Second trimester 3; Third trimester 2 | Unknown | Oligohydramnios and fetal growth restriction 2 | Died 3; Survived 9 | Survived 5; Ongoing pregnancy 2 | Spontaneous miscarriage 4; Induced labor 2; Preterm 4; Ongoing 2 | American J Obstet Gynecol |

| Shek et al[15], 2003 | 5 | Hong Kong | Unknown | Yes 4; Unknown 1 | Unknown | Died 2; Survived 2; Unknown 1 | Survived 5 | Preterm 4; Term 1 | Pediatrics |

| Robertson et al[16], 2004 | 1 | United States | Second trimester | Yes | Gestational diabetes | Survived | Survived | Term | Emerg Infect Dis |

| Stockman et al[17], 2004 | 1 | United States | First trimester | No | Premature rupture of membranes | Survived | Survived | Delivery at 36 wks gestation | Emerg Infect Dis |

| Yudin et al[18], 2005 | 1 | Canada | Third trimester | No | No | Survived | Survived | Term | Obstet. Gynecol |

| Wang et al[19], 2004 | 6 | China | Second trimester 2; Third trimester 4 | Unknown | Premature rupture of membranes 1; Nephrotic syndrome | Survived 6 | Survived 7; Died 1 | Preterm 3; Term 4 | Chin J Perinat Med |

Regarding MERS-CoV infection, Table 3 depicts eleven reported cases from six publications involving pregnancy; of these cases, ten women had negative perinatal outcomes, with six (54%) neonates requiring intensive care unit admission, and three (27%) dying during their hospitalizations[22-26]. The other four human coronavirus members merely elicit common colds. Fortunately, even if the majority of the related literature constitutes possible cases, there were no signs of vertical transmission identified between pregnant women and their corresponding neonates[29,30].

| Ref. | SS | Nationality | GAAI (wk) | ICUA | Maternal comorbid conditions | Maternal outcome | Fetal outcome | Delivery details | Journal |

| Memish et al[21], 2019 | 2 | Saudi | First trimester 1; Second trimester 1 | No | Hypertension 1 | Survived | Survived 2 | Term 2 | J Microbiol, Immunol Infect |

| Assiri et al[22], 2016 | 5 | Saudi | Second trimester 3; Third trimester 2 | Yes 5 | Preeclampsia 1; Asthma pulmonary fibrosis 1 | Survived 3; Died 2 | Died 2; Survived 3 | Intrauterine fetal death at 34 wk 1; Preterm 1; Term 3 | Clin Infect Dis |

| Payne et al[23], 2015 | 1 | Jordanian | Second trimester | No | None | Survived | Still birth | Still birth at 5 mo | J Infect Dis |

| Malik et al[24], 2016 | 1 | United Arab Emirates | Third trimester | Yes | None | Died | Survived | Caesarean section at 32 wk | Emerg Infect Dis |

| Jeong et al[25], 2017 | 1 | South Korean | Third trimester | No | Gestational diabetes | Survived | Survived | Term | J Korean Med Sci |

| Alserehi et al[26], 2016 | 1 | Saudi | Third trimester | Yes | Hypothyroidism | Survived | Survived | Caesarean section at 32 wk | BMC Infect Dis |

It has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 is closely related molecularly to SARS-CoV, with a 79.5% nucleotide sequence identity[3,5]. Additionally, the novel virus shares the same cell-binding receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2[31] with SARS-CoV, which is a key step in the pathogenic invasion of cells. SARS-CoV-2, like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, also leads to severe acute respiratory illness associated with a high mortality risk[32,33]. Combining the aforementioned presentations, one can reasonably conclude that adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes will likely emerge in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2.

In contrast to the adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes resulting from SARS or MERS infections, we achieved beneficial results for both the SARS-CoV-2 infected mother and the neonate. Importantly, due to her Wuhan-residence history and results of her CT scan, the patient was suspected of being infected with SARS-CoV-2, promptly isolated, and the related medical staffs and workers took protective measures to prevent themselves from infection. The results of nucleic acid testing then further confirmed our suspicions. Subsequently, given the confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection, her worsening clinical presentations, and the possible risks for both the pregnant woman and fetus, an emergency cesarean section was performed under negative pressure. In addition, the baby and his mother were separately quarantined and cared for after delivery. While still hospitalized, the patient became seronegative for SARS-CoV-2 and went into recovery with stable vital signs. Although the baby was healthy and did not show any signs of SARS-CoV-2 infection after three examinations of his lower respiratory tract samples, assessing the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection and coronavirus disease-2019 COVID-19 in pregnant women and their fetuses cannot be based solely on the success of one case.

Because it is a newly discovered coronavirus, there are currently no antiviral therapies or vaccines for SARS-CoV-2, and therefore, good medical care (primarily supportive treatments) may be the mainstay of management in the near term. Early observations revealed that the elderly and those with chronic diseases were prone to bearing the greatest burden of the disease, which may be due to the low immunocompetence of these individuals[11]. For this reason, the outcomes of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients depend on their own immunities to an extent.

Similarly, physiologic adaptations of the respiratory tract and immune system that occur during pregnancy increase susceptibilities to pulmonary infections[34,35]. Moreover, specific humoral and cell-mediated immunologic functions are inhibited during pregnancy, making pregnant women more susceptible to viral infection. Hence the severity of viral pneumonia during pregnancy is closely associated with these normal immune changes. Such hypotheses can be confirmed by previous epidemiologic data from other viruses, and the risks for developing viral pneumonia among pregnant women are significantly higher than for other general populations. Pregnant women infected with SARS appeared to have worse clinical manifestations and a higher fatality rate compared with nongravid women[21]. Viral pneumonias resulting from influenza-A, virus H1N1, and SARS have also all contributed to elevated rates of maternal mortality, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, and preterm delivery[36]. Although there is no direct evidence that infection with this new coronavirus results in severe maternal or perinatal outcomes, we need to continue to be vigilant to prevent this from occurring.

In addition, there are other aspects that may also contribute to a poor prognosis in pregnant women. A preliminary study revealed that SARS-CoV generally became transmissible after fever, so that fever was defined as a key marker to track. In contrast, current data indicate that the transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 occurs throughout the entire infectious period-including asymptomatic, mild, and treatment courses[12]. Also, it is conceivable that pregnant women are unknowingly and unpredictably exposed to infectious environments, and thus, the only way for them to remain safe is to distance themselves from the external milieu until after the basic reproductive ratio (R0) falls below 1.

Because our current understanding of the clinical features of SARS-CoV-2 infection is largely confined to severe pneumonia, respiratory failure, ARDS, cardiac injury, and fatal outcomes, diagnosis protocols on the basis of these case pneumonias may bias reporting toward more severe outcomes. However, the initial presentations of mild cough and fever in the progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection are not specific and cannot be clinically distinguished from other common infectious diseases. This may also lead SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals with low immunity to miss the timing of appropriate treatment(s). The effectiveness of some antiviral drugs is occasionally based only on the success of a few severe cases. Thus, when antiviral drugs are applied to pregnant patients, we need to carefully balance the efficacy and safety for both the mother and fetus. Our patient was fortunate to receive a favorable prognosis. Accordingly, the key steps in preventing the spread of the epidemic and allowing for potentially poor outcomes are to identify individuals at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This allows for prompt isolation and subsequent laboratory confirmation of infection as well as for admission of the confirmed cases for further assessment and appropriate treatment[10].

We achieved successful outcomes for both the SARS-CoV-2-infected mother and the neonate. Given the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19 pneumonia (although here only a single case), the identification, diagnosis, clinical course, management, and especially the positive outcomes are of significance for understanding the clinical manifestation, transmission, and related risks among special populations.

The authors are very grateful to all personnel of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Yueqing People’s Hospital for their work in caring for and managing the patient and her baby.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Phan T, Scicchitano P S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18987] [Cited by in RCA: 17628] [Article Influence: 3525.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Phan T. Novel coronavirus: From discovery to clinical diagnostics. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;79:104211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, Chu H, To KK, Yuan S, Yuen KY. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:221-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1813] [Cited by in RCA: 1950] [Article Influence: 390.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu Y, Ho W, Huang Y, Jin DY, Li S, Liu SL, Liu X, Qiu J, Sang Y, Wang Q, Yuen KY, Zheng ZM. SARS-CoV-2 is an appropriate name for the new coronavirus. Lancet. 2020;395:949-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, Berger A, Burguière AM, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra JC, Müller S, Rickerts V, Stürmer M, Vieth S, Klenk HD, Osterhaus AD, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967-1976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3277] [Cited by in RCA: 3314] [Article Influence: 150.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lu L, Liu Q, Du L, Jiang S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): challenges in identifying its source and controlling its spread. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:625-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, Rollin PE, Dowell SF, Ling AE, Humphrey CD, Shieh WJ, Guarner J, Paddock CD, Rota P, Fields B, DeRisi J, Yang JY, Cox N, Hughes JM, LeDuc JW, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ; SARS Working Group. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953-1966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3147] [Cited by in RCA: 3072] [Article Influence: 139.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, Brown CS, Drosten C, Enjuanes L, Fouchier RA, Galiano M, Gorbalenya AE, Memish ZA, Perlman S, Poon LL, Snijder EJ, Stephens GM, Woo PC, Zaki AM, Zambon M, Ziebuhr J. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol. 2013;87:7790-7792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 827] [Cited by in RCA: 868] [Article Influence: 72.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30096] [Article Influence: 6019.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, Bruce H, Spitters C, Ericson K, Wilkerson S, Tural A, Diaz G, Cohn A, Fox L, Patel A, Gerber SI, Kim L, Tong S, Lu X, Lindstrom S, Pallansch MA, Weldon WC, Biggs HM, Uyeki TM, Pillai SK; Washington State 2019-nCoV Case Investigation Team. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4155] [Cited by in RCA: 3820] [Article Influence: 764.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14869] [Cited by in RCA: 12968] [Article Influence: 2593.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC, Poon RW, Tsoi HW, Lo SK, Chan KH, Poon VK, Chan WM, Ip JD, Cai JP, Cheng VC, Chen H, Hui CK, Yuen KY. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6483] [Cited by in RCA: 5420] [Article Influence: 1084.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11224] [Cited by in RCA: 9312] [Article Influence: 1862.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, Ng WF, Ng TK, Shek CC, Ng PC, Lam PW, Ho LC, To WW, Lai ST, Yan WW, Tan PY. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 593] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen Y, Peng H, Wang L, Zhao Y, Zeng L, Gao H, Liu Y. Infants Born to Mothers With a New Coronavirus (COVID-19). Front Pediatr. 2020;8:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Robertson CA, Lowther SA, Birch T, Tan C, Sorhage F, Stockman L, McDonald C, Lingappa JR, Bresnitz E. SARS and pregnancy: a case report. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:345-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stockman LJ, Lowther SA, Coy K, Saw J, Parashar UD. SARS during pregnancy, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1689-1690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yudin MH, Steele DM, Sgro MD, Read SE, Kopplin P, Gough KA. Severe acute respiratory syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:124-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shek CC, Ng PC, Fung GP, Cheng FW, Chan PK, Peiris MJ, Lee KH, Wong SF, Cheung HM, Li AM, Hon EK, Yeung CK, Chow CB, Tam JS, Chiu MC, Fok TF. Infants born to mothers with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wong SF, Chow KM, de Swiet M. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and pregnancy. BJOG. 2003;110:641-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alfaraj SH, Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases & review of the literature. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:501-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Assiri A, Abedi GR, Al Masri M, Bin Saeed A, Gerber SI, Watson JT. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Infection During Pregnancy: A Report of 5 Cases From Saudi Arabia. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:951-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Payne DC, Iblan I, Alqasrawi S, Al Nsour M, Rha B, Tohme RA, Abedi GR, Farag NH, Haddadin A, Al Sanhouri T, Jarour N, Swerdlow DL, Jamieson DJ, Pallansch MA, Haynes LM, Gerber SI, Al Abdallat MM; Jordan MERS-CoV Investigation Team. Stillbirth during infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1870-1872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Malik A, El Masry KM, Ravi M, Sayed F. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus during Pregnancy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:515-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jeong SY, Sung SI, Sung JH, Ahn SY, Kang ES, Chang YS, Park WS, Kim JH. MERS-CoV Infection in a Pregnant Woman in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32:1717-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alserehi H, Wali G, Alshukairi A, Alraddadi B. Impact of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, Li J, Zhao D, Xu D, Gong Q, Liao J, Yang H, Hou W, Zhang Y. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2400] [Cited by in RCA: 2272] [Article Influence: 454.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wang S, Guo L, Chen L, Liu W, Cao Y, Zhang J, Feng L. A Case Report of Neonatal 2019 Coronavirus Disease in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:853-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 60.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai ACK, Zhou J, Liu W, Bi Y, Gao GF. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1725] [Cited by in RCA: 1876] [Article Influence: 208.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gagneur A, Dirson E, Audebert S, Vallet S, Quillien MC, Baron R, Laurent Y, Collet M, Sizun J, Oger E, Payan C. [Vertical transmission of human coronavirus. Prospective pilot study]. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2007;55:525-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gagneur A, Dirson E, Audebert S, Vallet S, Legrand-Quillien MC, Laurent Y, Collet M, Sizun J, Oger E, Payan C. Materno-fetal transmission of human coronaviruses: a prospective pilot study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:863-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, Chen YM, Wang W, Song ZG, Hu Y, Tao ZW, Tian JH, Pei YY, Yuan ML, Zhang YL, Dai FH, Liu Y, Wang QM, Zheng JJ, Xu L, Holmes EC, Zhang YZ. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6893] [Cited by in RCA: 7491] [Article Influence: 1498.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maxwell C, McGeer A, Tai KFY, Sermer M. No. 225-Management Guidelines for Obstetric Patients and Neonates Born to Mothers With Suspected or Probable Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e130-e137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Robinson DP, Klein SL. Pregnancy and pregnancy-associated hormones alter immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Horm Behav. 2012;62:263-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sheffield JS, Cunningham FG. Community-acquired pneumonia in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Komiya N, Gu Y, Kamiya H, Yahata Y, Yasui Y, Taniguchi K, Okabe N. Household transmission of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus in Osaka, Japan in May 2009. J Infect. 2010;61:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |