Published online Jun 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2623

Peer-review started: February 19, 2020

First decision: April 14, 2020

Revised: May 6, 2020

Accepted: May 23, 2020

Article in press: May 23, 2020

Published online: June 26, 2020

Processing time: 126 Days and 4.8 Hours

Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor (ECSCSs) is rare.

We present a rare case of primary ECSCSs in the left ovary. A 39-year-old female patient had persistent dull pain in the lower abdomen for more than 1 mo, and she was initially diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease at a hospital. The patient received transabdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection at our hospital and finally diagnosed with ECSCSs. After the operation, the patient received eight courses of cisplatinum + etoposide + bleomycin chemotherapy treatment and no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis was found in a 2-year follow-up period.

Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma is similar to the ovary sex cord-stromal tumor, especially when the cord-like structure is obvious. The clinical diagnosis for this tumor is difficult before surgery and pathology examination. The necessary immunohistochemical markers are of positive significance for assisting diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Core tip: In the clinicopathological diagnosis, if ovarian tumor has the morphology of sex cord-stromal tumor, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of endometrioid carcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor. Extensive and comprehensive sampling of specimens can often find focal areas of classical endometrioid carcinoma. The necessary immunohistochemical markers are of positive significance for assisting diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

- Citation: Wei XX, He YM, Jiang W, Li L. Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(12): 2623-2628

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i12/2623.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2623

Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma is one of the most common epithelial malignancies of the ovary and accounts for 10% to 25% of all primary ovarian cancers. Ovarian endometrioid carcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor (ECSCSs) is a very rare subtype of it, which is very similar to the ovary sex cord-stromal tumor, especially when the cord-like structure is obvious, which can cause diagnostic difficulties. This article analyzes the histomorphology and immunophenotype of a primary ovarian ECSCSs and reviews the related literature to raise awareness of this type of tumor.

A 39-year-old female patient with a menstrual history of 13 years (8 d/29 d) had persistent dull pain in the lower abdomen for more than 1 mo, and she was diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease at a local hospital. She used condom for contraception.

Specialized physical examination showed that a solid-cystic mass can be touched in the left posterior upper part of the uterus, about 10 cm in diameter, which was hard and inactive, and had a clear boundary.

The level of CA125 was 82.2 U/mL, with the rest tumor markers within the normal range.

B-ultrasonography found that the solid-cystic mass in left adnexa area was 11 cm × 7.4 cm × 9.8 cm in size, and it was rich in blood flow signals. Abdominal pain was relieved after anti-inflammatory treatment.

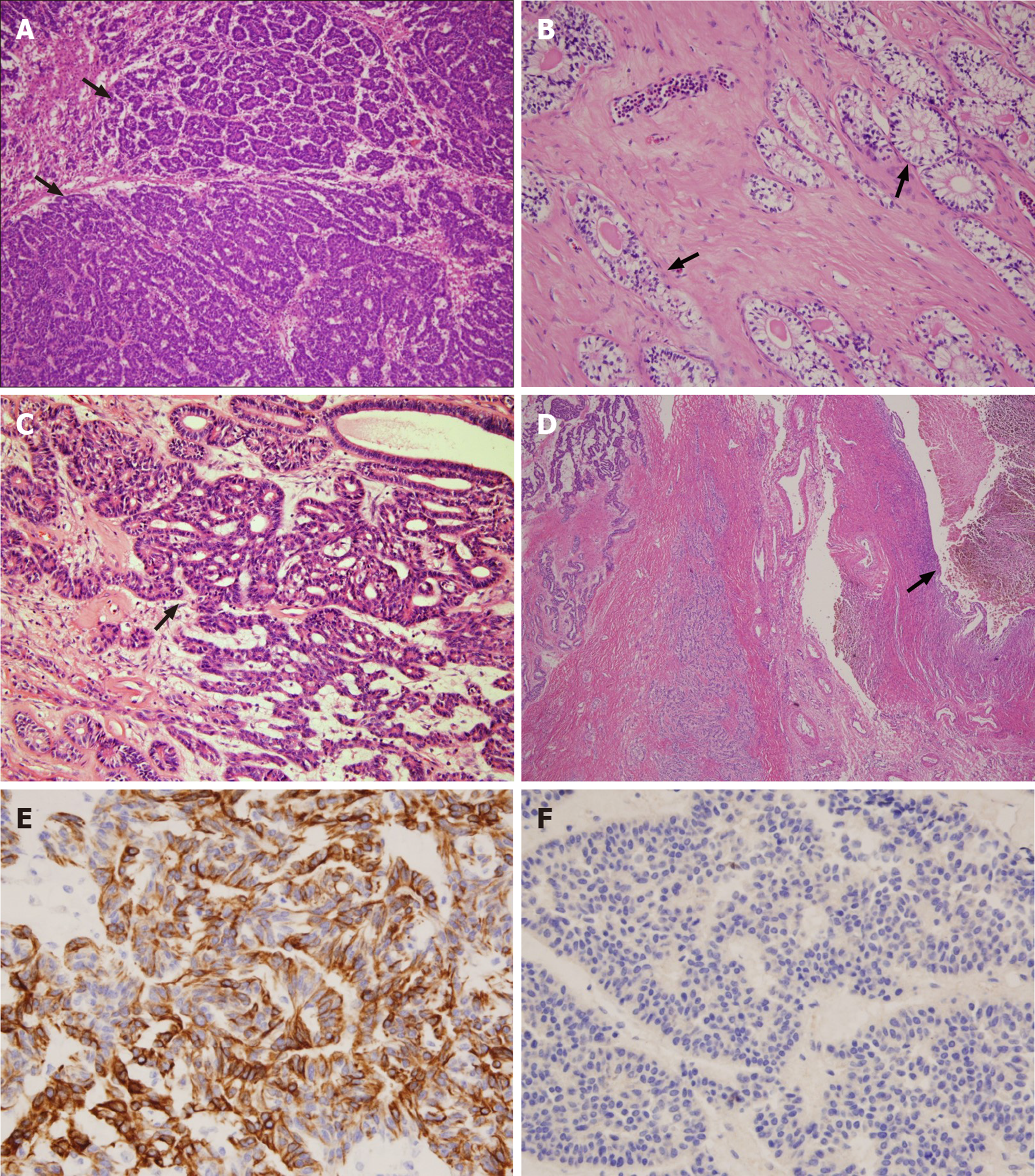

Gross examination showed that the mass was dark brown, with a size of 11 cm × 6 cm × 6 cm and a smooth surface; the cut surface was solid, thick-nodular, tender in texture, and grayish and gray-yellow in color, and there were small cysts of different sizes (0.5-1.5 cm in diameter) scattered inside it, without capsule fluid (Figure 1). Microscopic examination revealed that most of the tumors consisted of solid cell nests, micro-adenoids, and trabeculae, and there were granulosa cell tumor-like structures (Figure 2A), and small tubular structures that resembled Sertoli cell tumor (Figure 2B). Small areas had an adenoid structure, and some glandular cavities contained mucus. Tumor cells were round or oval, of medium size, with less cytoplasm; the nucleus was ovoid, the nucleolus were small, and the mitotic figure was four per ten high-power fields. Typical glands and squamous metaplasia of endometrioid carcinoma appeared in local areas (Figure 2C). There was spindle cell proliferation in part of mesenchyme that was similar to ovarian fibroma. Bleeding and necrosis were seen in some areas of the tumor tissue, and endometriotic cysts were seen next to the tumor (Figure 2D). Tumor cells diffusely expressed VIM, PCK, CK7 (Figure 2E), WT1, ER, PR, CD10, CD56, and β-catenin, and partially expressed EMA, P16, and P53. The Ki67 proliferation index was approximately 10%, and all tumor tissues did not express α-inhibin (Figure 2F), calretinin, CD99, sall4, CgA, syn, ck20, muc-2, muc-5, ck10/13, desmin, myogenin, myoD1, or SMA. Then, a diagnosis of ECSCSs of the left ovary was made, with no tumor involving the remaining tissue and no lymph node metastasis.

The diagnosis of ECSCSs of the left ovary was confirmed by pathology examination.

The patient received a transabdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection.

After the operation, the patient received eight courses of cisplatinum + etoposide + bleomycin (BEP) chemotherapy treatment and no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis was found in a 2-year follow-up period.

ECSCSs is a rare variant of endometrioid carcinoma, which was first reported by Young et al[1] in 1982. Trabecular structures, solid tubular structures, chrysanthemum-like structures, or micro-adenoic structures were observed by light microscopy. It is easy to confuse with true sex cord-stromal tumors, such as Sertoli cell tumour, Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, or granulosa cell tumor. At present there are about tencases reported in China[2].

ECSCSs is more common in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women, with the age of onset ranging from 22 to 89 years old, with the majority being 50 to 70 years old. The clinical manifestation of patients is pelvic mass with or without pain, usually without abnormal levels of sex hormones, some patients may have vaginal bleeding, and about 80% of patients may have elevated serum CA125 levels[2]. The patient in the case was 39 years old and abdominal pain was the first symptom, with elevated CA125.

ECSCSs is generally large, and the diameters reported in the literature are mostly 10-20 cm[3]. The cut surface is cystic or solid-cystic. The cyst contents are mostly bloody liquid and the papillary structure of the capsule wall is often not obvious, which is different from ovarian serous or mucinous carcinoma[4]. Some cases may have nodular solid area protruding into the cystic spaces. Its cystic wall or solid area seldom has a gray-yellow appearance that is specific to sex cord-stromal tumors[5]. In this case, the tumor had a maximum diameter of 11 cm and was solid-cystic, which is consistent with the characteristics of previous reports. ECSCSs often consists of two histomorphologies; one of them is typical endometrioid carcinoma, and most of the cancer tissues are well-differentiated, showing adenoid or papillary structure with a similar size and shape, and often accompanied by squamous metaplasia[6,7]. According to the vast majority of current literature reports, this typical endometrioid carcinoma structure tends to occupy a smaller proportion in ECSCSs[8]. The other one is the component that resembles ovarian cord-stromal tumors, and the tumor cells can be arranged in a microadenoid pattern, with secretions in the glandular cavity, which is similar to Call-Exner bodies in adult granulosa cell tumor; or it may be hollow tubular and thin funicular, which resembles Sertoli cell tumor-like structure. It can also have large areas of spindle cells, and even obvious luteinization or fibrosis. In this case, more than 90% of the area were thin cord-like structures resembling granulosa cell tumor and tubular structures resembling Sertoli cell tumor, less than 10% of the area were the structures of classic endometrioid carcinoma, and there were cell clusters with focal squamous metaplasia and endometrium cysts nearing the tumor. Therefore, a wide range of materials should be taken during the gross examination, and the typical area of endometrioid carcinoma should be carefully searched during the reading. If squamous cell metaplasia, adenofibular fibrosis background, or endometriotic cysts nearing the tumor are visible in sex cord stromal-like tumors, ECSCSs should be highly suspected.

ECSCSs is similar to the following ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors and needs to be identified by combining histomorphology and immunohistochemistry: (1) Adult granulosa cell tumor. It is common in 45-55-year-old females. The age of onset is lower than that of ECSCSs, and patients often have elevated estrogen levels. Histologically, the nucleus of granulosa cell tumors is round, oval, or polygonal, with lighter staining, plainly visible nuclear grooves, and a coffee bean-like appearance. The ECSCSs’ cell nucleus is usually round and the chromatin is coarse-grained. The nucleus is easy to see, and its glandular cavity may contain mucus; (2) Sertoli cell tumor or Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors differentiate toward the testis and are more common in young women between the ages of 20 and 30. Patients often have smaller mass, often accompanied by symptoms of excessive androgen secretion. Histologically, the tumor cells of the Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor constitute hollow or solid tubular structures, similar to the focal or extensive small, well-differentiated hollow or solid tubular structures in ECSCSs. Regarding immunohistochemical markers, Sertoli-Leydig cells are positive for α-inhibin and calretinin but negative for CK7 and EMA; (3) Island-type or trabecular type carcinoid. There are many patients with carcinoid syndrome. Histologically, the cancer cells are arranged in island-like, sieve-like, fine funicular or ribbon-like shape, the cells are consistent, the chromatin is uniform and fine, and cancer nest mesenchyme may show hyaline degeneration. Immunohistochemically, neuroendocrine markers such as Syn, CgA, and CD56 are positive; and (4) Metastatic poorly differentiated carcinoma. When Krukenberg tumor presents small tubular differentiation, it is easy to be confused with ECSCSs. The majority of metastatic ovarian cancers are bilateral, clinically often showing the primary cancer foci, and signet-like tumor cells can be found in microscopic examination, lacking the structure of typical endometrioid carcinoma. Epithelial-derived immunohistochemical markers such as CK20, CEA, and CDX-2 are positive.

Most papers consider that ECSCSs is a low-grade endometrioid carcinoma[3]. Although the structural characteristics that are similar to sex cord-stromal tumors may occur, complete resection of the tumor, disappearance of clinical symptoms, and reduction of CA125 levels to normal can extend the patient’s survival time, especially when the tumor is confined to the ovary, the patient’s survival time is longer and the prognosis is better. After radical surgery in the present case, BEP regimen chemotherapy was administered for eight courses, and at the 2-year follow-up visit, no sign of recurrence was found.

We have reported a rare case of ovarian ECSCSs. It was finally diagnosed after operation and pathology examination, but the clinical diagnosis for this case was difficult before surgery and pathology examination. The necessary immunohistochemical markers are of positive significance for assisting diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hosseini M, Serhiyenko VA S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Young RH, Prat J, Scully RE. Ovarian endometrioid carcinomas resembling sex cord-stromal tumors. A clinicopathological analysis of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:513-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ma YH, Zhao QX, Li HX. Ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling sex-cord tumors: a chlincopathologic study. Linchuang Yu Shiyan Binglixue Zazhi. 2013;29:45-48. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Wang Q, Zhang HP, Zhuang YL. [Ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor: report of a case]. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2017;46:350-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taylor J, McCluggage WG. Ovarian Sex Cord-stromal Tumors With Melanin Pigment: Report of a Previously Undescribed Phenomenon. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boussios S, Moschetta M, Zarkavelis G, Papadaki A, Kefas A, Tatsi K. Ovarian sex-cord stromal tumours and small cell tumours: Pathological, genetic and management aspects. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;120:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Young RH. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumours and their mimics. Pathology. 2018;50:5-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Young RH. Ovarian Sex Cord-Stromal Tumors: Reflections on a 40-Year Experience With a Fascinating Group of Tumors, Including Comments on the Seminal Observations of Robert E. Scully, MD. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1459-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Katoh T, Yasuda M, Hasegawa K, Kozawa E, Maniwa J, Sasano H. Estrogen-producing endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling sex cord-stromal tumor of the ovary: a review of four postmenopausal cases. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |