Published online Oct 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i11.477

Peer-review started: June 11, 2018

First decision: June 20, 2018

Revised: July 30, 2018

Accepted: August 12, 2018

Article in press: August 12, 2018

Published online: October 6, 2018

Processing time: 110 Days and 0.8 Hours

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is a type of extramedullary solid haematological tumour. Myeloid sarcoma is classified into two types based on whether onset of the disease is complicated by haematologic diseases: extramedullary infiltration of leukaemia (leukaemic MS) and isolated myeloid sarcoma. The incidence of isolated myeloid sarcoma is low. In particular, isolated myeloid sarcoma involving the pancreas is extremely rare and prone to misdiagnosis. This case report describes the long and eventful diagnostic process of a case of myeloid sarcoma involving the pancreas and orbit. Due to a lack of typical clinical manifestations and imaging characteristics, the patient underwent several rounds of treatment without a confirmed diagnosis. Eventually, the final diagnosis was pathologically confirmed using several types of biopsies and immunohistochemical detection. To date, this type of disease has not been reported in the literature. This case report describes the detailed diagnostic process and discusses the strategies used for diagnosis, which will facilitate the diagnosis of such diseases in the future.

Core tip: Although isolated myeloid sarcoma is difficult to diagnose, multi-site lesions provide indications for diagnosis. This case report describes isolated myeloid sarcoma occurring in both the pancreas and the orbit.

- Citation: Zhu T, Xi XY, Dong HJ. Isolated myeloid sarcoma in the pancreas and orbit: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(11): 477-482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i11/477.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i11.477

Myeloid sarcoma (MS) is also known as extramedullary myeloid tumour, granulocytic sarcoma, or chloroma. The 2001 World Health Organization classification of tumours of lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues unified these terms under MS[1]. MS is a type of malignant solid tumour that forms from the infiltration of the organs and tissues outside the bone marrow by immature myeloid cells[2]. MS mostly occurs in the lymph nodes, bones, periosteum, soft tissues, and skin[3] but rarely occurs in the gastrointestinal tract, orbits, and pancreas[4-6]. This case report describes the diagnosis of a case of isolated MS occurring simultaneously in the pancreas and orbit and aims to provide strategies for clinical diagnosis in such cases.

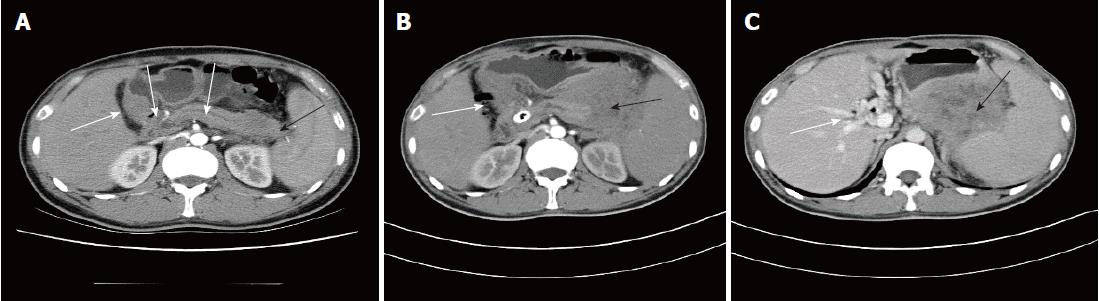

The patient was a 36-year-old male, who was admitted to the hospital due to persistent abdominal pain. This patient had no remarkable medical history. Starting in July 2015, the patient experienced repeated episodes of unexplained upper abdominal pain and experienced no other accompanying symptoms. After review of the patient’s past medical records, multiple laboratory tests at other hospitals indicated elevated levels of pancreatic enzymes ranging from 213-341 IU/L (less than 3-fold of the upper limit of the normal range [35-140 IU/L]) combined with slight exudation around the pancreas, and gallstones. His condition improved when he was treated for pancreatitis. As pancreatitis caused by gallstones could not be excluded, cholecystectomy was performed. After surgery, his symptoms repeatedly relapsed. In October 2015, right eyelid oedema occurred intermittently, which was not treated. In April 2016, the right eye became increasingly swollen until protrusion of the eyeball occurred. Orbital computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed at other hospitals and indicated space-occupying lesions, but no further treatment was given. In May 2016, the patient again experienced abdominal pain and was diagnosed at the Department of Gastroenterology at a hospital specializing in the standardization of residency training. Laboratory tests showed slightly elevated liver and pancreatic enzymes and normal routine blood and autoantibody test results. Levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and other tumour markers were also normal. A contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan indicated a blur gap between fat around the pancreatic tail and between the spleen and stomach. A circle-like cystic low-density shadow was observed in the gap between the stomach and pancreas without clear enhancement. The pancreatic duct and the bile ducts inside and outside the liver were also slightly dilated (Figure 1A). The possibility of pancreatitis was considered. However, the patient’s abdominal pain relapsed repeatedly, and the evidence for “pancreatitis” was not sufficient. His medical history and related tests excluded the possibility of pancreatitis caused by drugs, metabolism, and autoimmunity. Therefore, endoscopic ultrasound was performed, the results of which indicated an uneven echo of the pancreatic tail and body. Echo-free fluid exudation was observed around the pancreatic tail, and a hypoechoic, solid space-occupying lesion was visible at the uncinate process with uneven echo. Scattered hyperechoic areas were also observed. A pancreatic head space-occupying lesion and degeneration due to pancreatitis were considered. Needle aspiration biopsy of the space-occupying lesion of the pancreatic uncinate process was performed using an endoscopic ultrasound. The pathologic analysis revealed local tissue necrosis, and the patient exhibited obstructive jaundice after the operation. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed to place a metallic stent, and dark-red tissue discharge was observed during the procedure. The tissue was sent for pathological examination, but no tumour cells were detected. The patient’s symptoms were treated, and he was discharged after they improved.

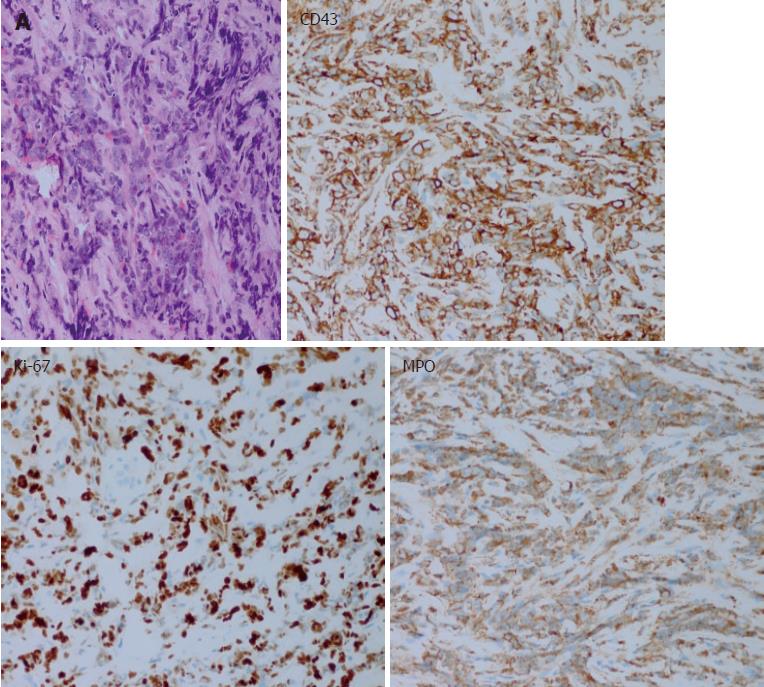

In July 2016, the patient’s abdominal pain recurred. Positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT) indicated low-density lesions resembling lumps in the pancreatic tail. The shadow had a ring shape and glucose metabolism was abnormally high. Therefore, the lesion was considered an inflammatory pseudotumour. The pancreatic head region exhibited shadowy patches, glucose metabolism was slightly changed, and another CT performed using the same machine showed a space-occupying lesion in the corresponding region as well as an abnormal density change. Thus, the lesion was considered a benign lesion (possibly an inflammatory lesion). Glucose metabolism was abnormally high in the capsule area that formed a cord outside the right orbit, and a benign lesion was diagnosed (possibly an inflammatory pseudotumour). The aetiology of the lesion in this patient remained unclear, and the possibility of a haematologic malignancy was considered. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, but obvious abnormalities were not detected. Therefore, percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy of the hypoechoic area of the pancreatic tail was conducted under ultrasonography guidance. The result showed heterotypic cells with a flaky appearance arranged in cord-like shape indicating infiltrate growth (Figure 2A), and the pathologic analysis indicated a malignant tumour. In addition, the morphology suggested a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. However, considering the long medical history of the patient and because tumour markers and imaging findings did not support the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, immunohistochemistry was performed after a consultation with pathologists. The results showed that the lesion was negative for CEA(M), CEA(P), CK(AE1/AE3), CD56, CgA, Syn, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, CD10, CD20, CD3, and MUM1, and the lesion was positive for Ki-67 (+ 80%), P53 (approximately 50%), CD43, and MPO (Figure 2). These results supported the diagnosis of myeloid leukaemia with pancreatic involvement. Bone marrow puncture and biopsy were performed again, and the results were almost normal. No further treatment was administered.

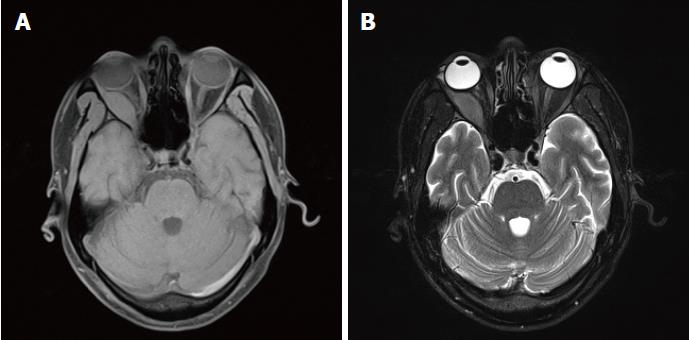

In October 2016, the patient’s right eye protruded significantly and was accompanied by severe pain; the eyelids were also unable to close. The patient underwent surgical treatment at another hospital, and the pathologic analysis suggested a malignant tumour. Although the combined immunodetection did not support an epithelial-derived tumour, myeloid leukaemia and osteosarcoma were still considered. After a consultation with pathologists at our hospital and the addition of a myeloperoxidase (MPO) (+) test, which was combined with other immunohistochemical results, myeloid sarcoma was considered. By then, the diagnosis of myeloid sarcoma was clear, and the patient was transferred to the Department of Haematology for treatment. On November 23, 2016, a CT examination revealed a mass shadow with a diameter of approximately 8.6 cm in the pancreatic tail. The density was not uniform, and a contrast-enhanced CT scanning showed significant enhancement. The demarcation between the lesion and the posterior wall of the stomach and the splenic hilum was not clear. The intrahepatic general bile duct exhibited dilation and pneumatosis, and spongy-like changes were observed in the portal vein (Figure 1B, C). An IDA chemotherapy regimen was initiated in December. After three cycles of chemotherapy, the disease progressed. Radiochemotherapy (the lesion in the pancreatic tail, 24Gy/12F) was then given. However, in April 2017, the patient experienced pain due to the distention of the right orbit. An orbital MRI scan (T1-weighted imaging (Figure 3A) and T2-weighted imaging (Figure 3B) showed a uniform-signal intensity mass in the right lateral rectus area and right optic nerve compression with displacement, suggesting recurrence. No abnormalities were observed on bone puncture. The patient was then treated with radiotherapy again, during which multiple masses developed throughout the body. Ultrasound results suggested the possibility of the infiltration. Bone puncture was performed again, and the result suggested that primary granulocytes accounted for 38.4% of the lesion. Consequently, the patient was switched to DAC (decitabine) + CAG chemotherapy regimen. By February 2018, bone puncture results indicated remission, but the extramedullary disease continued to progress.

MS often occurs simultaneously with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) as the extramedullary manifestation of AML or during extramedullary relapse after remission of AML following treatment,that is extramedullary infiltration of leukaemia (leukaemic MS). However the isolated MS(non-leukaemic MS) is clinically rare and prone to misdiagnosis. Isolated MS refers to the occurrence of MS in the absence of any medical history of blood pathology at the onset of the disease. The lesion simply manifests as an extramedullary mass, which does not develop into AML within 30 d. This type of MS is very rare[7] and accounts for only 2%-14% of all AML cases[8]. Since isolated MS does not have a specific clinical manifestation, approximately 75%-86% of patients with this disease are misdiagnosed during the initial diagnosis[9]. The pancreas is rarely involved in cases of isolated MS, and the rate of misdiagnosis is therefore very high. The patient in this report visited several hospitals, and his diagnosis was confirmed after 15 mo.

The patient in this report visited various hospitals and was subjected to many laboratory tests due to persistent upper abdominal pain. He was treated for pancreatitis based on increased levels of pancreatic enzymes (less than 3-times the upper limit of the normal value), and his condition improved. Initially, abdominal CT also indicated the possibility of pancreatitis, but his medical history and related examinations had already excluded pancreatitis induced by drugs, alcohol, metabolism, and infection as well as biliary pancreatitis. Additionally, a pancreatic space-occupying lesion developed with progression of the disease. Therefore, further identification and diagnosis appeared to be particularly important. Was the pancreatic space-occupying lesion indicative of pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, or some other disease? The patient also had an orbital space-occupying lesion; should the disease be explained with “monism” or “dualism”? The patient’s medical history, contrast-enhanced CT, PET-CT, and the tumour marker expression levels did not support the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and mass-forming pancreatitis was not excluded. If “monism” had been used to explain the disease, the diseases that simultaneously involve multiple systems, include autoimmune diseases, vasculitis-related diseases, multiple endocrine-related diseases, and rare tumour and blood system diseases, would not have be excluded. This case involved both the pancreas and the orbit. First, IgG4-related autoimmune diseases were considered. However, no IgG4 was found in the serum, puncture specimen IgG4 staining was negative, and other autoimmune diseases had already been ruled out. Pathology is the gold standard for diagnosis. Accordingly, in this case, endoscopic ultrasound-guided pancreatic biopsy and ultrasound-guided pancreatic biopsy were performed. The initial pathology result showed local necrotic tissue. Additional pathological findings suggested the possibility of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Finally, after a consultation with pathologists, we further investigated endocrine-related and blood system disease-related immunohistochemistry and the disease was eventually diagnosed.

Early diagnosis and treatment can delay the progression of isolated MS to AML, which may result in a relatively good prognosis. However, as the clinical manifestations are primarily extramedullary mass-related symptoms that lack specific imaging and pathological features, diagnosing isolated MS is difficult. In these cases, immunohistochemistry is the key to the diagnosis of isolated MS. MPO, lysozyme, CD68, and other myeloid cell-related markers are the most sensitive and effective markers for MS[10]. Studies have found that MPO, CD68, CD20, and CD43 detection can confirm the diagnosis up to 96% of MS cases[11]. The key to the diagnosis of this patient was also immunohistochemistry.

Patients with isolated MS of the pancreas often visit the Department of Gastroenterology for abdominal symptoms, and they are often misdiagnosed with chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic tumours. As the first attending physician in this case, we must have a sense of differentiation for atypical cases and select a reasonable diagnostic method in a timely manner. In this case, the patient was diagnosed multiple times before the disease was confirmed, and his diagnosis was the result of the joint efforts of many disciplines, including gastroenterology, radiology, and pathology. In addition, although simultaneous occurrence of lesions in the pancreas and orbit is rare, detection of lesions at multiple locations has also provided guidance for the clinical consideration of related rare diseases. The aim of this paper is to provide ideas for clinical diagnosis. However, as this type of case is rare, studies of additional cases are needed to develop a deeper understanding of this disease.

A 36-year-old male with symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain and intermittent right eyelid oedema exhibiting space-occupying lesions in the pancreas and orbit.

Isolated myeloid sarcoma.

Pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and lymphoma should be excluded.

Normal tumour marker levels, slightly elevated liver and pancreatic enzymes, and normal routine blood and autoantibody test results.

A malignant tumour positive for Ki-67 (+ 80%), P53 (approximately 50%), CD43, and MPO was indicated.

Chemotherapy combined with radiochemotherapy.

A case of isolated myeloid sarcoma occurring simultaneously in the pancreas and orbit has never been reported.

Isolated myeloid sarcoma.

This case contributes to deepening our understanding of the diagnosis of isolated myeloid sarcoma. We should combine various laboratory test results, especially pathologic and immunohistochemical results, to assist in diagnosis. Surgery is not recommended for these cases, and minimally invasive methods are preferred for pathological examinations because surgery may delay treatment and affect the prognosis of patients. In addition, we should have a sense of differentiation for atypical cases, and the monism explanation should be considered first for multi-site lesions.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Gupta V, Aseni P, Saligram S, Coskun A S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press 2001; . |

| 2. | Wiseman DH, Das M, Poulton K, Liakopoulou E. Donor cell leukemia following unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for primary granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Paydas S, Zorludemir S, Ergin M. Granulocytic sarcoma: 32 cases and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2527-2541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kitagawa Y, Sameshima Y, Shiozaki H, Ogawa S, Masuda A, Mori SI, Teramura M, Masuda M, Kameoka S, Motoji T. Isolated granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine successfully treated with chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2008;87:410-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maka E, Lukáts O, Tóth J, Fekete S. Orbital tumour as initial manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia: granulocytic sarcoma: case report. Pathol Oncol Res. 2008;14:209-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schäfer HS, Becker H, Schmitt-Gräff A, Lübbert M. Granulocytic sarcoma of Core-binding Factor (CBF) acute myeloid leukemia mimicking pancreatic cancer. Leuk Res. 2008;32:1472-1475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Constantinou J, Nitkunan T, Al-Izzi M, McNicholas TA. Testicular granulocytic sarcoma, a source of diagnostic confusion. Urology. 2004;64:807-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Imagawa E, Matsuda K, Hidaka E, Uhara M, Uehara T, Sano K, Yamauchi K. A case of myeloid sarcoma diagnosed by FISH. Rinsho Byori. 2007;55:1084-1087. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Wang CS, Li H, Shi FY, Gao CF, Yin J, Yuan XT. Clinical pathological analysis of 4 cases of isolated granulocytic sarcoma. Linchuang Yu Shiyan Binglixue Zazhi. 2009;643-645. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Alexiev BA, Wang W, Ning Y, Chumsri S, Gojo I, Rodgers WH, Stass SA, Zhao XF. Myeloid sarcomas: a histologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic study. Diagn Pathol. 2007;2:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Julia A, Nomdedeu JF. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis or eosinophilic chloroma? Acta Haematol. 2004;112:164-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |