Published online Feb 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i5.1009

Peer-review started: October 31, 2022

First decision: November 11, 2022

Revised: November 24, 2022

Accepted: January 16, 2023

Article in press: January 16, 2023

Published online: February 16, 2023

Processing time: 106 Days and 0.2 Hours

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been shown to be correlated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. However, further investigation is needed to understand how T2DM characteristics affect the prognosis of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

To assess the effect of T2DM on CHB patients with cirrhosis and to determine the risk factors for HCC development.

Among the 412 CHB patients with cirrhosis enrolled in this study, there were 196 with T2DM. The patients in the T2DM group were compared to the remaining 216 patients without T2DM (non-T2DM group). Clinical characteristics and outcomes of the two groups were reviewed and compared.

T2DM was significantly related to hepatocarcinogenesis in this study (P = 0.002). The presence of T2DM, being male, alcohol abuse status, alpha-fetoprotein > 20 ng/mL, and hepatitis B surface antigen > 2.0 log IU/mL were identified to be risk factors for HCC development in the multivariate analysis. T2DM duration of more than 5 years and treatment with diet control or insulin ± sulfonylurea significantly increased the risk of hepatocarcinogenesis.

T2DM and its characteristics increase the risk of HCC in CHB patients with cirrhosis. The importance of diabetic control should be emphasized for these patients.

Core Tip: This retrospective study assessed the risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). A total of 412 CHB patients were enrolled in this study. T2DM, male sex, alcohol abuse, alpha-fetoprotein > 20 ng/mL, and hepatitis B surface antigen > 2.0 log IU/mL were identified to be risk factors for HCC development. T2DM duration and treatment were also significantly related to HCC development. Thus, T2DM and T2DM characteristics affect the prognosis of CHB patients with cirrhosis.

- Citation: Li MY, Li TT, Li KJ, Zhou C. Type 2 diabetes mellitus characteristics affect hepatocellular carcinoma development in chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(5): 1009-1018

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i5/1009.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i5.1009

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem worldwide[1]. It is estimated that over 257 million people are chronically infected with HBV worldwide, causing 887000 deaths annually[2]. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) can lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. CHB accounts for over 50% of cases of HCC globally, which is the most common type of liver cancer[3]. HCC is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in China[4]. Many non-HBV factors, including age, sex, alcohol consumption, smoking, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), may increase HCC risk among CHB patients[5,6].

Currently, T2DM affects more than 440 million individuals globally[7]. China has the most people affected by T2DM with 110 million estimated T2DM diagnoses[8]. T2DM is a leading cause of death due to renal and heart complications[9] as well as an increased risk of multiple cancers[10]. Patients with T2DM have a 2.5-4.0-fold risk of developing HCC[11]. The precise mechanism of how T2DM affects the development of HCC remains unclear, although it may be related to insulin resistance and insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling pathways[12]. This study investigated the relationship between T2DM clinical characteristics and HCC development in T2DM patients with CHB.

This was a retrospective study consisting of consecutive CHB patients at the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University in Zhengzhou, China during the period of December 2013 to February 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity for more than 6 mo; (2) Valid clinical characteristics and laboratory outcomes; (3) No hepatotrophic virus coinfection; (4) Presence of cirrhosis; (5) No alcoholic hepatic diseases or HCC; and (6) No type 1 DM. The final number of patients included in this study was 412. Patients were divided into a T2DM group (n = 196) and a non-T2DM group (n = 216). This study was conducted under compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (KY2021031).

Patient data were obtained from the electronic medical record database of the hospital. The prothrombin time and international normalized ratio were measured with an ACL TOP coagulation analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Beckman Coulter, Sydney, NSW, Australia). Platelet count was monitored with an LH 750 Automated Hematology Analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Beckman Coulter). Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, albumin, total bilirubin, and creatinine levels were measured using an AU5800 Clinical Chemistry Analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Beckman Coulter). The serum HBV-DNA level was quantified by polymerase chain reaction using a Roche LightCycler (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). HBsAg and hepatitis B e-antigen were determined using an AutoLumo A2000Plus Chemiluminescence Detector (Autobio, Zhengzhou, China).

Continuous variables are expressed as medians (the first to third quartiles), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess continuous variables. The χ2 test or Fisher’s test was used to analyze categorical variables. The incidence of HCC was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Cox regression was used to screen and identify factors associated with mortality and hepatocarcinogenesis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was also performed to identify potential factors associated with T2DM. The model for end-stage liver disease score was calculated according to the standard formula[13]. The following cutoffs of analyzed factors were based on previous reports: Age of 65 years[14], HBsAg of 2.0 log IU/mL[15], and HBV-DNA of 20000 IU/mL[16]. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS software package (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

A total of 412 CHB patients with cirrhosis were enrolled in this study, including 196 patients with pre-existing T2DM at baseline and 216 patients without. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Compared to patients in the non-T2DM group, patients in the T2DM group had significantly lower prothrombin time [11.8 (10.8-14.1) vs 10.4 (9.6-11.3), respectively, P < 0.001] and international normalized ratio [1.05 (0.96-1.24) vs 0.94 (0.87-1.01), respectively, P < 0.001]. Since nucleos(t)ide analogues (NUCs) may affect HCC development, we compared the use of NUCs between the two groups. We found that the proportion of different HBV therapies between the two groups did not differ significantly (Supplementary Table 1). Therefore, the HBV therapy may not affect the risk of HCC in this study. The other baseline characteristics did not show significant differences between the two groups.

| Characteristic | T2DM at baseline, n = 196 | Non-T2DM at baseline, n = 216 | P value |

| Age in yr | 55 (50-62) | 54 (49-62) | 0.090 |

| Female sex | 69 (35.2) | 72 (33.3) | 0.690 |

| Smoking status | 98 (50.0) | 125 (57.9) | 0.114 |

| Alcohol abuse status | 76 (38.8) | 74 (34.3) | 0.358 |

| Dyslipidemia | 64 (32.7) | 58 (26.9) | 0.235 |

| Ascites | 9 (4.6) | 15 (6.9) | 0.400 |

| Esophagogastric varices | 6 (3.1) | 12 (5.6) | 0.238 |

| PT | 10.4 (9.6-11.3) | 11.8 (10.8-14.1) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 0.94 (0.87-1.01) | 1.05 (0.96-1.24) | < 0.001 |

| AST in IU/mL | 25 (20-38) | 27 (20-45) | 0.389 |

| ALT in IU/mL | 26 (19-34) | 28 (20-44) | 0.101 |

| Platelet count as × 109/ L | 177 (132-203) | 161 (112-207) | 0.105 |

| AFP in ng/mL | 1.24 (0.56-20.83) | 2.36 (1.53-25.00) | 0.761 |

| GGT in U/L | 29 (17-58) | 33 (19-80) | 0.062 |

| Total bilirubin in μmol/L | 15.0 (10.5-18.5) | 15.1 (11.1-24.9) | 0.096 |

| Albumin in g/L | 39.7 (33.1-42.8) | 37.8 (32.3-41.0) | 0.090 |

| MELD score | 6 (5-8) | 6 (5-10) | 0.191 |

| HBsAg in log IU/mL | 2.50 (1.91-2.68) | 2.64 (2.22-2.69) | 0.104 |

| HBV DNA in IU/mL | 19500 (1260-234000) | 23850 (8738-329000) | 0.936 |

| Creatinine in µmol/L | 60 (52-74) | 61 (50-74) | 0.379 |

| HBeAg positivity | 50 (25.5) | 56 (24.1) | 0.727 |

| Antiviral treatment | 137 (69.9) | 144 (66.7) | 0.526 |

| Duration of T2DM in yr | |||

| 0-2.0 | 44 (22.4) | ||

| 2.1-5.0 | 42 (21.4) | ||

| 5.1-10.0 | 52 (26.5) | ||

| > 10.0 | 58 (29.6) | ||

| T2DM treatment | |||

| Metformin ± sulfonylurea | 112 (57.1) | ||

| Insulin ± sulfonylurea | 50 (25.5) | ||

| Diet alone | 34 (17.3) |

In the T2DM group, 22.4% (44/196) of patients had been diagnosed with T2DM for less than 2.0 years, 21.4% (42/196) for 2.1-5.0 years, 26.5% (52/196) for 5.1-10.0 years, and 29.6% (58/196) for more than 10.0 years. Among all the T2DM patients, 57.1% (112/196) were treated with metformin with or without sulfonylurea treatment, 25.5% (50/196) were treated with insulin with or without sulfonylurea treatment, and 17.3% (34/196) controlled T2DM with diet alone.

The factors related to hepatocarcinogenesis were assessed (Table 2). The analyzed factors included age, sex, smoking status, alcohol abuse status, dyslipidemia, T2DM, ascites, esophagogastric varices, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), HBsAg, hepatitis B e-antigen, HBV-DNA, and antiviral treatment. The univariate analysis showed that sex (P < 0.001), smoking status (P = 0.013), T2DM (P = 0.002), and ascites (P = 0.016) were significantly related to hepatocarcinogenesis. Then, the multivariate analysis was conducted to analyze the factors associated with hepatocarcinogenesis. The results showed that sex [hazard ratio (HR) = 3.47, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.36-8.89, P = 0.010], alcohol abuse status (HR = 1.38, 95%CI: 0.80-1.68, P = 0.008), T2DM (HR = 6.73, 95%CI: 2.77-16.36, P < 0.001), AFP (HR = 3.89, 95%CI: 1.06-14.27, P = 0.041), and HBsAg (HR = 4.10, 95%CI: 1.52-11.12, P = 0.005) were significantly related with hepatocarcinogenesis.

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age in yr, > 65 vs ≤ 65 | 1.16 (0.63, 2.10) | 0.649 | 1.38 (0.62, 3.11) | 0.434 |

| Sex, male vs female | 4.37 (1.98, 9.64) | < 0.001 | 3.47 (1.36, 8.89) | 0.010 |

| Smoking status, yes vs no | 1.97 (1.15, 3.38) | 0.013 | 1.46 (0.61, 3.45) | 0.394 |

| Alcohol abuse status, yes vs no | 1.83 (0.44, 2.55) | 0.558 | 1.38 (0.80, 1.68) | 0.008 |

| Dyslipidemia, yes vs no | 1.58 (0.30, 2.09) | 0.090 | 0.80 (0.36, 1.79) | 0.589 |

| Diabetes mellitus, yes vs no | 2.54 (1.41, 4.59) | 0.002 | 6.73 (2.77, 16.36) | < 0.001 |

| Ascites, yes vs no | 2.68 (1.20, 5.98) | 0.016 | 1.41 (0.31, 6.43) | 0.660 |

| Esophagogastric varices, yes vs no | 1.20 (0.37, 3.87) | 0.766 | 0.62 (0.13, 2.97) | 0.552 |

| AFP in ng/mL, > 20 vs ≤ 20 | 1.85 (0.98, 3.51) | 0.059 | 3.89 (1.06, 14.27) | 0.041 |

| γ-GTP in U/L, per SD | 1.24 (0.52, 2.14) | 0.692 | 1.34 (0.75, 3.21) | 0.530 |

| HBsAg, > 2.0 log IU/mL vs ≤ 2.0 log IU/mL | 1.74 (0.43, 2.28) | 0.277 | 4.10 (1.52, 11.12) | 0.005 |

| HBV DNA, ≤ 20000 IU/mL vs > 20000 IU/mL | 0.46 (0.20, 1.07) | 0.072 | 1.09 (0.38, 3.15) | 0.877 |

| HBeAg positivity, yes vs no | 0.59 (0.28, 1.28) | 0.181 | 0.54 (0.20, 1.49) | 0.236 |

| Antiviral treatment, yes vs no | 0.27 (0.16, 2.14) | 0.365 | 0.74 (0.33, 1.67) | 0.475 |

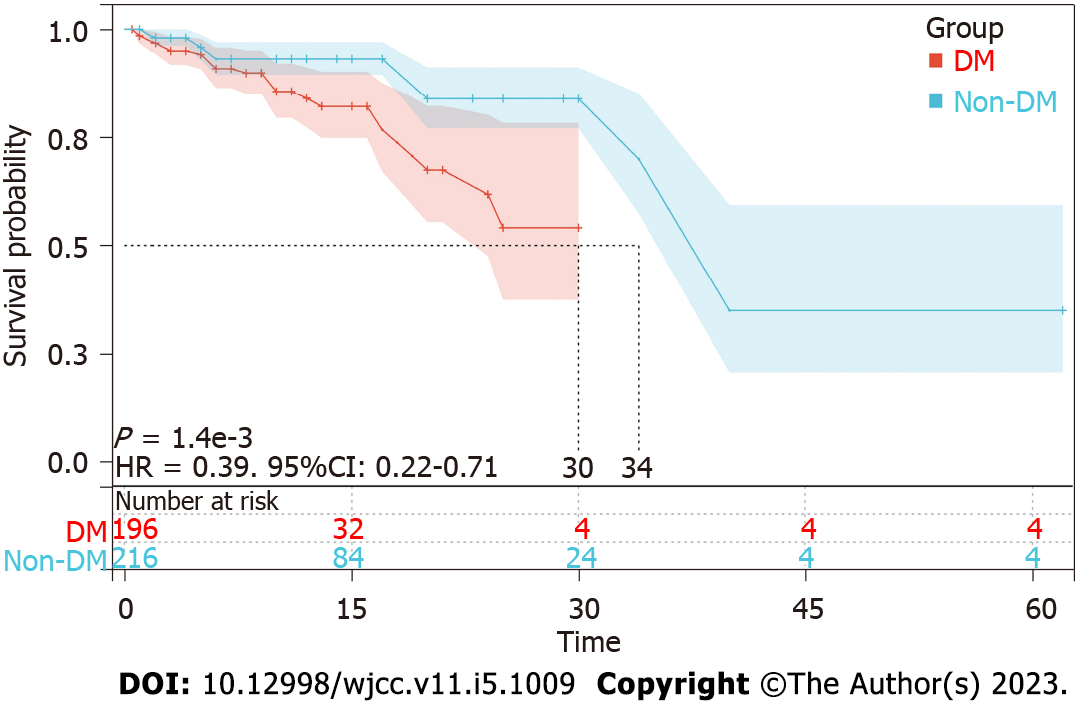

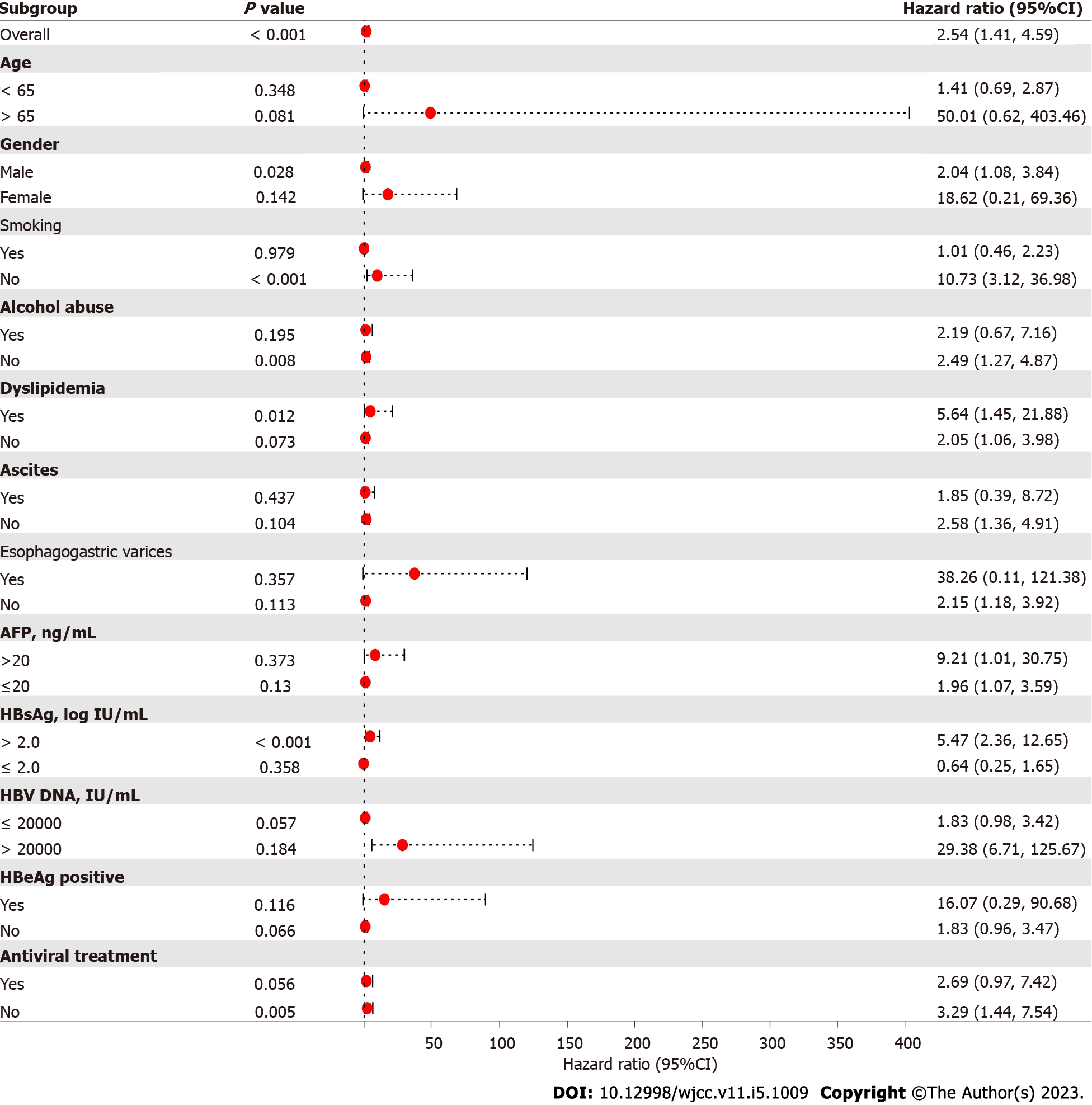

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that the hepatocarcinogenesis probability of the T2DM group and non-T2DM group was significantly different (Figure 1). The median time to hepatocarcinogenesis for the T2DM group and non-T2DM group was 30 mo and 34 mo, respectively. We then analyzed the relationship between T2DM and hepatocarcinogenesis among all subgroups (Figure 2). T2DM and hepatocarcinogenesis were significantly correlated in the following subgroups: Males (HR = 2.04, 95%CI: 1.08-3.84, P = 0.028), non-smokers (HR = 10.73, 95%CI: 3.12-36.98, P < 0.001), patients without alcohol abuse (HR = 2.49, 95%CI: 1.27-4.87, P = 0.008), patients with HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL (HR = 5.47, 95%CI: 2.36-12.65, P < 0.001), and patients not treated with antiviral medication (HR = 3.29, 95%CI: 1.44-7.54, P = 0.005).

Since T2DM was shown to be associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in CHB patients, we analyzed the relationship between T2DM characteristics and hepatocarcinogenesis in CHB patients with T2DM. We found that patient age over 65 years old (P < 0.001), male sex (P = 0.049), AFP > 20 ng/mL (P = 0.002), HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL (P = 0.001), or receipt of antiviral treatment (P = 0.007) were significantly correlated with hepatocarcinogenesis in the T2DM group (Table 3). Among T2DM characteristics, T2DM duration of more than 5 years (HR = 6.74, 95%CI: 2.36-19.29, P < 0.001), insulin ± sulfonylurea therapy (HR = 1.45, 95%CI: 0.26-7.96, P = 0.041), and diet control only (HR = 10.70, 95%CI: 2.91-39.31, P < 0.001) were significantly correlated with hepatocarcinogenesis in the T2DM group.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age > 65 yr | 23.54 | 4.59-120.74 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 3.64 | 1.01-13.20 | 0.049 |

| Smoking | 3.10 | 0.85-11.38 | 0.088 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.38 | 0.11-1.31 | 0.125 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.56 | 0.50-4.85 | 0.440 |

| Ascites | 0.50 | 0.07-3.60 | 0.489 |

| Esophagogastric varices | 0.54 | 0.05-6.34 | 0.623 |

| AFP > 20 ng/mL | 17.44 | 2.86-106.23 | 0.002 |

| γ-GTP in U/L, per SD | 2.31 | 1.55-14.01 | 0.762 |

| HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL | 11.93 | 2.82-50.41 | 0.001 |

| HBV DNA > 20000 IU/mL | 0.39 | 0.09-1.60 | 0.190 |

| HBeAg positivity | 0.96 | 0.29-3.11 | 0.941 |

| Antiviral treatment | 0.19 | 0.06-0.64 | 0.007 |

| T2DM duration in yr | |||

| ≤ 5 | - | - | - |

| > 5 | 6.74 | 2.36-19.29 | < 0.001 |

| T2DM therapy | |||

| Yes/metformin ± sulfonylurea | - | - | - |

| Yes/insulin ± sulfonylurea | 1.45 | 0.26-7.96 | 0.041 |

| Yes/diet control only | 10.70 | 2.91-39.31 | < 0.001 |

T2DM is a major public health problem in China[17]. It has been suggested that T2DM is a risk factor for HCC development, liver disease progression, and mortality in CHB patients[18]. However, it remains controversial whether T2DM is related to HCC development. Results from the current study suggested that the presence of T2DM significantly increased the risk of HCC development in CHB patients with cirrhosis. Cox regression analysis showed that sex, alcohol abuse status, T2DM, AFP, and HBsAg were significantly related with hepatocarcinogenesis. The T2DM characteristics, including duration and treatment, were found to be significantly related with hepatocarcinogenesis.

In the present study, the incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis was significantly correlated to sex (P = 0.010), alcohol abuse status (P = 0.008), T2DM (P < 0.001), AFP (P = 0.041), and HBsAg (P = 0.005). A recent study showed that gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (γ-GTP) levels were related with the risk of HCC among HBV patients on NUC therapy[19]. But in this study, the level of γ-GTP did not differ between the two groups in both the univariate and multivariate analyses (P = 0.692 and 0.530, respectively). Thus, whether γ-GTP levels affect the prognosis of CHB patients still needs to be further verified. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed that the probability of hepatocarcinogenesis in the T2DM group was significantly different from that in the non-T2DM group. These results suggested that T2DM was an independent risk factor for HCC development. These findings were consistent with prior studies[20,21]. The subgroup analysis showed that the effect of T2DM on HCC development was stronger in CHB patients in the subgroups of male gender, non-smoker, no alcohol abuse, HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL, and no antiviral treatment. This difference may be due to the limited number of patients, which still needs to be validated in further studies.

It is notable that T2DM characteristics were associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in this study. In cirrhotic CHB patients with T2DM, patients who were over 65 years old or male, who had AFP > 20 ng/mL or HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL, or who received antiviral treatment had a significantly increased risk of hepatocarcinogenesis. T2DM duration of more than 5 years was found to be significantly correlated to the incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis. It had a 6.74-fold increased risk for HCC compared to in T2DM patients with a duration of less than 5 years.

Moreover, T2DM patients who were treated with only diet control or insulin ± sulfonylurea therapy were at a higher risk for HCC development. However, it is still unknown whether different treatment strategies affect HCC development. It has been reported that the use of insulin can elevate the risk of HCC[9,22]. On the contrary, metformin treatment was reported to be associated with a reduced risk of HCC[12]. A large-scale study also showed that the use of metformin among DM patients can significantly reduce the HCC risk in chronic hepatitis C patients[23]. The underlying mechanism has not been fully understood, but it may be related with the anti-proliferative and immune-modulating effect of metformin[24]. Although evidence suggests that sulfonylureas can increase the risk of HCC[12,25], we found that the use of metformin with or without sulfonylurea had a significantly lower risk of HCC. These results suggest that good diabetic management and appropriate therapy are crucial in cirrhotic CHB patients with T2DM. There are some limitations for this study. This is a single center retrospective study, and the sample size was small. Some details of T2DM patients were not collected, which limited further analysis. Thus, the results need to be validated in larger multicenter studies in the future.

In conclusion, T2DM was found to be related to a poor CHB prognosis. Analysis suggested that patients who were male, who abused alcohol, or who had AFP > 20 ng/mL and HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL were at a higher risk for poor outcomes. T2DM characteristics, including T2DM duration of more than 5 years, diet control, and insulin ± sulfonylurea therapy, significantly increased the risk of hepatocarcinogenesis. These findings confirmed the importance of diabetic management in CHB patients with cirrhosis. The exact mechanism of how T2DM affects HCC development still warrants further study.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been shown to be correlated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development. However, the T2DM characteristics that affect HCC are unknown.

T2DM affects more than 440 million individuals globally. T2DM is a leading cause of death due to renal and heart complications as well as an increased risk of multiple cancers. Understanding the correlation between T2DM and HCC will benefit these patients.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between T2DM clinical characteristics and HCC development in pre-existing T2DM patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Among 412 CHB patients enrolled in this study, there were 196 patients with T2DM. The patients were divided into the T2DM group and the non-T2DM group (n = 216). Clinical characteristics and outcomes of the two groups were compared.

T2DM was found to be significantly related to hepatocarcinogenesis in this study. In the multivariate analysis, T2DM, male sex, alcohol abuse status, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) > 20 ng/mL, and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) > 2.0 log IU/mL were identifeid to be risk factors for HCC development. T2DM duration and therapy significantly increased the risk of hepatocarcinogenesis.

T2DM was found to be related to a poor CHB prognosis. Male sex, alcohol abuse status, AFP > 20 ng/mL and HBsAg > 2.0 log IU/mL were also significantly related with poor outcomes. T2DM characteristics, including T2DM duration more than 5 years and treatment of diet control or insulin ± sulfonylurea significantly increased the risk of hepatocarcinogenesis.

These findings confirmed the importance of diabetic management in CHB patients. The exact mechanism of how T2DM affects HCC development still warrants further study.

The authors are very grateful to Dr. Wang Yan (First Clinical Medical College, Shanxi Medical University) for the statistical review.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Soldera J, Brazil; Yu ML, Taiwan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Yuen MF, Chen DS, Dusheiko GM, Janssen HLA, Lau DTY, Locarnini SA, Peters MG, Lai CL. Hepatitis B virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lee HM, Banini BA. Updates on Chronic HBV: Current Challenges and Future Goals. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2019;17:271-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xie Y. Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1018:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu XF, Xing H, Han J, Li ZL, Lau WY, Zhou YH, Gu WM, Wang H, Chen TH, Zeng YY, Li C, Wu MC, Shen F, Yang T. Risk Factors, Patterns, and Outcomes of Late Recurrence After Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Multicenter Study From China. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 65.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35-S50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1691] [Cited by in RCA: 1791] [Article Influence: 85.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73 Suppl 1:4-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 820] [Cited by in RCA: 1329] [Article Influence: 332.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Ma RCW. Epidemiology of diabetes and diabetic complications in China. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1249-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang L, Shao J, Bian Y, Wu H, Shi L, Zeng L, Li W, Dong J. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among inland residents in China (2000-2014): A meta-analysis. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7:845-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan MM, Curley SA, Li D, Kaseb A, Davila M, Abdalla EK, Javle M, Moghazy DM, Lozano RD, Abbruzzese JL, Vauthey JN. Association of diabetes duration and diabetes treatment with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:1938-1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR, Petrelli J, Thun MJ. Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1160-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Allaire M, Nault JC. Type 2 diabetes-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: A molecular profile. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2016;8:53-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Plaz Torres MC, Jaffe A, Perry R, Marabotto E, Strazzabosco M, Giannini EG. Diabetes medications and risk of HCC. Hepatology. 2022;76:1880-1897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3554] [Article Influence: 187.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Foster GR, Irving WL, Cheung MC, Walker AJ, Hudson BE, Verma S, McLauchlan J, Mutimer DJ, Brown A, Gelson WT, MacDonald DC, Agarwal K; HCV Research, UK. Impact of direct acting antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1224-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang C, Yang Z, Wang Z, Dou X, Sheng Q, Li Y, Han C, Ding Y. HBV DNA and HBsAg: Early Prediction of Response to Peginterferon α-2a in HBeAg-Negative Chronic Hepatitis B. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, Jen CL, You SL, Lu SN, Huang GT, Iloeje UH; REVEAL-HBV Study Group. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2309] [Cited by in RCA: 2363] [Article Influence: 124.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Song P, Yu J, Chan KY, Theodoratou E, Rudan I. Prevalence, risk factors and burden of diabetic retinopathy in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2018;8:010803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shyu YC, Huang TS, Chien CH, Yeh CT, Lin CL, Chien RN. Diabetes poses a higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis B: A population-based cohort study. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:718-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang CF, Jang TY, Jun DW, Ahn SB, An J, Enomoto M, Takahashi H, Ogawa E, Yoon E, Jeong SW, Shim JJ, Jeong JY, Kim SE, Oh H, Kim HS, Cho YK, Kozuka R, Inoue K, Cheung KS, Mak LY, Huang JF, Dai CY, Yuen MF, Nguyen MH, Yu ML. On-treatment gamma-glutamyl transferase predicts the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients. Liver Int. 2022;42:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shin HS, Jun BG, Yi SW. Impact of diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2022;28:773-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu GM, Zeng HD, Zhang CY, Xu JW. Key genes associated with diabetes mellitus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2019;215:152510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hsiang JC, Gane EJ, Bai WW, Gerred SJ. Type 2 diabetes: a risk factor for liver mortality and complications in hepatitis B cirrhosis patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:591-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tsai PC, Kuo HT, Hung CH, Tseng KC, Lai HC, Peng CY, Wang JH, Chen JJ, Lee PL, Chien RN, Yang CC, Lo GH, Kao JH, Liu CJ, Liu CH, Yan SL, Bair MJ, Lin CY, Su WW, Chu CH, Chen CJ, Tung SY, Tai CM, Lin CW, Lo CC, Cheng PN, Chiu YC, Wang CC, Cheng JS, Tsai WL, Lin HC, Huang YH, Yeh ML, Huang CF, Hsieh MH, Huang JF, Dai CY, Chung WL, Chen CY, Yu ML; T-COACH Study Group. Metformin reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence after successful antiviral therapy in patients with diabetes and chronic hepatitis C in Taiwan. J Hepatol. 2022;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhang Y, Wang H, Xiao H. Metformin Actions on the Liver: Protection Mechanisms Emerging in Hepatocytes and Immune Cells against NASH-Related HCC. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee JY, Jang SY, Nam CM, Kang ES. Incident Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Patients Treated with a Sulfonylurea: A Nationwide, Nested, Case-Control Study. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |