Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1536

Peer-review started: August 23, 2021

First decision: October 16, 2021

Revised: October 29, 2021

Accepted: January 5, 2022

Article in press: January 5, 2022

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 171 Days and 22.4 Hours

Castleman disease (CD) and TAFRO syndrome are very rare in clinical practice. Most clinicians, especially non-hematological clinicians, do not know enough about the two diseases, so it often leads to misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis.

To explore the clinical features and diagnosis of CD and TAFRO syndrome.

We retrospectively collected the clinical and laboratory data of 39 patients who were diagnosed with CD from a single medical center.

Clinical classification identified 18 patients (46.15%) with unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) and 21 patients (53.85%) with multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), the latter is further divided into 13 patients (33.33%) with idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease-not otherwise specified (iMCD-NOS) and 8 patients (20.51%) with TAFRO syndrome. UCD and iMCD are significantly different in clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis. However, a few patients with MCD were diagnosed as UCD in their early stage. There was a correlation between two of Thrombocytopenia, anasarca and elevated creatinine, which were important components of TAFRO syndrome. In UCD group, the pathologies of lymph modes were mostly hyaline vascular type (13/18, 72.22%), however plasma cell type or mixed type could also appear. In iMCD-NOS group and TAFRO syndrome group, the pathologies of lymph mode shown polarity of plasma cell type and hyaline vascular type respectively. Compared with patients with TAFRO syndrome, patients with iMCD-NOS were diagnosed more difficultly.

The clinical and pathological types of CD are not completely separate, there is an intermediate situation or mixed characteristics between two ends of clinical and pathological types. The clinical manifestations of patients with CD are determined by their pathological type. TAFRO syndrome is a special subtype of iMCD with unique clinical manifestations.

Core Tip: This study is a real-world study. Through a retrospective analysis of the diagnosis and treatment process of 39 patients with Castleman disease (CD), we conclude that the clinical classification and pathological classification of CD are not completely independent, and there is an intermediate state or transition state between the two extreme manifestations. TAFRO syndrome is still classified as a special subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD). TAFRO syndrome is easier to identify than iMCD-not otherwise specified because of its unique pathological and clinical features.

- Citation: Zhou QY. Castleman disease and TAFRO syndrome: To improve the diagnostic consciousness is the key. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1536-1547

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1536

Emergency medicine is a symptomatic discipline. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of diseases need the combination of general thinking and specialized knowledge, while lymph node enlargement is an area often involved in the differential diagnosis of diseases. A disease in this field has gained increasing attention of doctors in recent years, namely, Castleman disease (CD). CD is reactive lymphadenopathy with unknown causes. It was first officially reported by Professor Castleman in 1954. The reported lesion was a tumor-like mass confined to the mediastinum. Histology shown obvious hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles and capillaries[1]. In 1969, Flendrig et al[2] proposed another morphological subtype of CD characterized by plasma cell proliferation and often accompanied by systemic symptoms. With the deepening of clinical and pathological research, CD was clinically divided into unicentric CD (UCD) and multicentric CD (MCD)[3,4]; Pathologically, it was divided into hyaline vascular type, plasma cell type, and mixed type. UCD generally involves only a single lymph node region, and the pathological type is mostly hyaline vascular type, mainly relying on surgical treatment. MCD mostly involves multiple lymph node regions. The pathological type is mostly plasma cell type, accompanied by systemic symptoms. Drugs are the main treatment.

From 2004 to 2005, Kojima et al[5,6] reported many cases of cryptogenic MCD and pointed out that unlike Western researchers who reported that MCD was mostly human herpesvirus (HHV)-8 positive, Japanese MCD was mostly HHV-8 negative, that is, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD). In 2008, Kojima et al[7] classified 28 patients with iMCD into idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy (IPL) and non-IPL according to their pathological characteristics and summarized their clinical characteristics. In 2010, Takai et al[8] first named TAFRO syndrome: T (thrombocytopenia), A (anasarca), F (fever), R (reticulin fibrosis), and O (organomegaly). In 2012, the Fukushima and Nagoya conferences in Japan clearly defined TAFRO syndrome as a systemic inflammatory disease accompanied by a series of clinical symptoms such as thrombocytopenia, systemic edema, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organ enlargement[9]. Studies have found that the non-IPL MCD reported by Carbone et al[10] is highly similar to TAFRO syndrome in clinical features, therefore, TAFRO syndrome is also called Caslteman–Kojima disease. In 2016, Iwaki et al[11] divided iMCD into TAFRO syndrome and unspecified iMCD (idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease-not otherwise specified, iMCD-NOS).

TAFRO syndrome was first proposed by Japanese scholars, and subsequent reports and studies were mainly came from Japan[12]. At present, the most authoritative diagnostic criteria for TAFRO syndrome were put forward by Iwaki et al[11] and Masaki et al[13] respectively in 2016, and Masaki et al[14] updated the diagnostic criteria in 2019.

The research on iMCD and TAFRO syndrome is still in the clinical exploration stage, and its etiology and pathogenesis are unclear. TAFRO syndrome or MCD is rare clinically, patients often seek medical treatment with systemic symptoms, and non-hematological doctors often do not know enough about this disease. Hence, it is easy to cause misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis. In 2020, we reported two consecutive cases who were diagnosed with TAFRO syndrome according to their findings of lymph node and renal biopsy[15]. To further understand the clinical features of various types of CD and the internal relationship between TAFRO syndrome and iMCD, we collected CD cases diagnosed and treated in Peking University People's Hospital in the last 5 years and etrospectively analyzed their clinical data.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Shougang Hospital (approval number: IRBK-2021-010-01). Written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Shougang Hospital for retrospective nature of the study.

The selection of CD cases mainly depended on the pathological diagnosis. Patients with single or multiple lymph node enlargement in a single region were classified as UCD, and patients with lymph node enlargement in two or more regions were classified as MCD.

The diagnosis criteria of TAFRO syndrome adopted the updated Masaki standard in 2019[14] which were shown in Table 1.

| Diagnostic criteria for TAFRO syndrome |

| Primary criteria |

| Edema: Including pleural and abdominal effusion and systemic edema |

| Thrombocytopenia: Platelet count ≤ 105/uL before myelosuppression |

| Systemic inflammation: Fever of unknown origin, body temperature exceeding 37.5°C, and/or serum CRP ≥ 2 mg/dL |

| Secondary criteria |

| Pathological manifestations of CD-like lymph nodes |

| Bone marrow reticular fibrosis and/or increased bone marrow megakaryocyte count |

| Mild organ enlargement: Including liver, spleen, and lymph node enlargement |

| Progressive renal dysfunction |

| TAFRO syndrome can be diagnosed after meeting at least two of all three main criteria and four secondary criteria, and excluding malignant tumor, autoimmune disease, infection, POEMS syndrome, liver cirrhosis, TTP/HUS, etc. |

Using "Castleman disease" or "TAFRO syndrome" as the key words, with either of them included in discharge diagnosis,we searched in the inpatient medical record system from January 2015 to October 2019. 48 cases were eligibable. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) no lymph node biopsy results, and CD was a clinically suspected diagnosis; (2) CD was a previous diagnosis, not the cause of this admission; (3) other definite diagnosis were present, such as POEMS syndrome (P, polyneuropathy; O, organomegaly; E, endocrinopathy; M, monoclonal; S, skin changes), lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), etc.; (4) authoritative pathological institutions denied the diagnosis of CD; and (5) age < 18 years. A total of nine cases (including one case of POEMS syndrome, one case of lymphoma, two cases of SLE, one case of Sjogren's syndrome, one case with a past history of CD, one case without lymph node biopsy, and two cases with uncertain clinical diagnosis). Finally, 39 cases were enrolled.

SPSS 23.0 was used for statistical analysis. Counting data were expressed as a constituent ratio or percentage, and measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD (normal-distribution data) or median and quartile (non-normal-distribution data). The difference analysis was performed using t test (normal-distribution measurement data), nonparametric test (non-normal-distribution measurement data), and Fisher accurate test (sample size less than 40, counting data or classified variables). P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

See Table 2. The enrolled patients were all Chinese, mainly distributed in North China. Both HHV-8 and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. The rage of age was from 21 years to 80 years. The average age of the three groups was not statistically significantly different. But the minimum and maximum age were distributed in the iMCD-NOS group, including the only child patient (< 18 years old) enrolled in this study. The ratio of male and female in three grops was similar. Urban patients were dominant in the UCD group, while rural patients were dominant in the TAFRO syndrome group. A statistically significant difference was found between the two groups.

| UCD (n = 18) | iMCD-NOS (n = 13) | TAFRO (n = 8) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 41.17 ± 18.23 | 47.23 ± 22.09 | 40.50 ± 9.04 | 0.530 |

| Male/female | 10/8 | 7/6 | 4/4 | 1.000 |

| Rural/urban | 5/13a | 6/7 | 6/2a | 0.085 |

| Time of diagnosis (median, months) | NA | 12 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Systemic manifestations | ||||

| Fever | 2 | 10 | 8 | |

| Splenomegaly | 0 | 5 | 3 | |

| Edema/polyserous cavity effusion | 0 | 0 | 8 | |

| Bronchiolitis obliterans | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rash | 0 | 5 | 3 | |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Abnormal renal function | 0 | 1 | 7 | |

| Laboratory examination | ||||

| White blood cell1 | ||||

| Decreased | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Raise | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| Hemoglobin1 | 0.000 | |||

| Decrease (n) | 2 | |||

| Average (g/L) | 132.00 ± 19.985 | 99.31 ± 27.41 | 79.57 ± 21.08 | |

| Platelet1 | ||||

| Decreased | 0 | 3 | 8t | |

| Raise | 2 | 6 | 0 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | NA | 91.09 ± 59.14 | 141.55 ± 64.31 | 0.000 |

| Albumin (g/L)1 | 39.61 ± 5.52 | 31.65 ± 7.39 | 22.79 ± 9.26 | 0.000 |

| Direct anti-human ball test was positive (n, %) | NA | 9/13 | 6/6 | |

| IL-6 (median, pg/mL) (n) | NA | 47.35 (8) | 12.65 (8) | 0.040 |

| VGEF (median, pg/mL) (n) | NA | NA | > 800 (5) | |

| Ferritin > five times normal value | NA | 4/13 | 1/8 | |

| Elevated LDH | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Elevated ALP | 1/18 | 3/13 | 6/8 | |

| ANA positive (titer > 1:40) | 2/18 | 8/13 | 2/8 | |

| Elevated polyclonal immunoglobulin | 0 | 9/13 | 1/8 | |

| Hemophilia syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1/8 | |

| Pathological type | ||||

| Hyaline vascular type | 13 | 0 | 5/8 | |

| Plasma cell type | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Mixed type | 2 | 9 | 2/8 | |

| No evidence of lymph node biopsy | 0 | 0 | 1/8 | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Biopsy only, treatment unknown | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Symptomatic treatment only | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Simple surgical resection | 18 | 0 | 0 | |

| Glucocorticoid alone | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Hormones combined with chemotherapy2 | 0 | 51 | 2 | |

| Hormone combined with rituximab | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hormone combined with tozumab | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Prognosis | ||||

| Loss of contact | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Improved | 16 | 6 | 7 | |

| Relapse | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Solid cancer occurred during the follow-up | 2b | 1c | 0 | |

| Transformation into lymphoma | 0 | 1d | 0 | |

| Death | 0 | 2 | 0 |

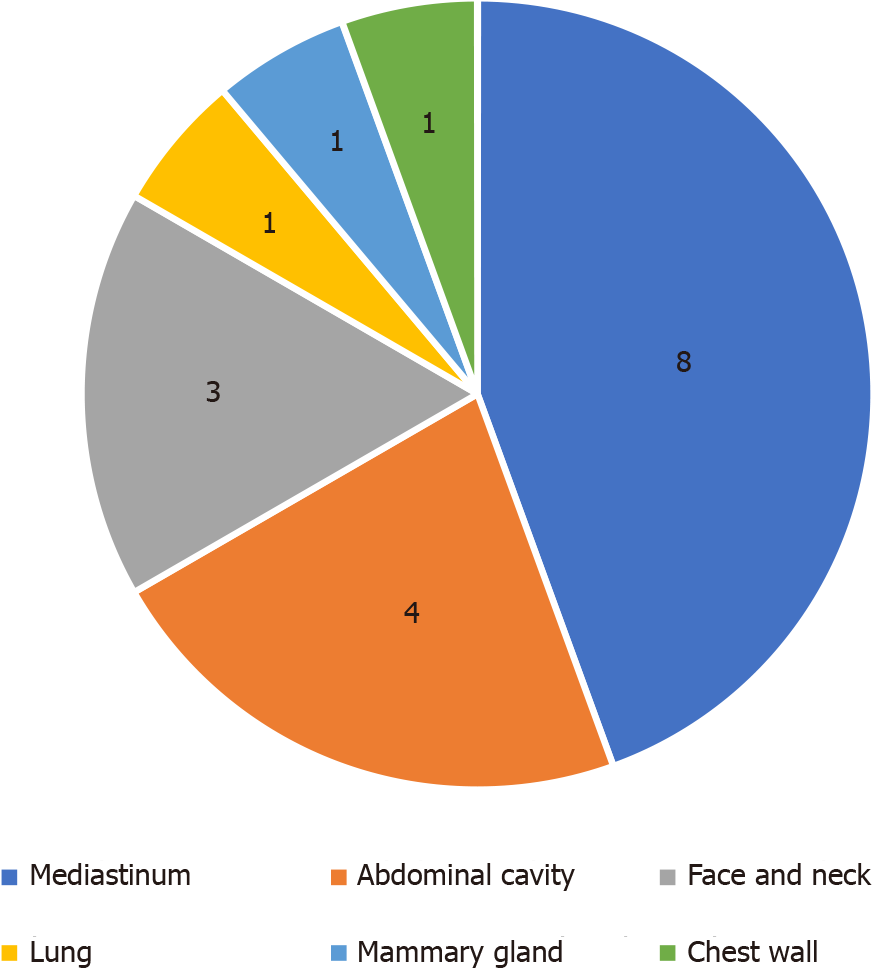

Most patients with UCD were diagnosed by chance or by physical examination (10/18, 55.56%), followed by symptoms caused by enlarged lymph node compression, including irritating dry cough (3/18, 16.67%), local pain (2/18, 11.11%), obstructive jaundice (1/18, 5.56%), and chest tightness (1/18, 5.56%). The distribution of enlarged lymph nodes is shown in Figure 1. Only a few patients also had a fever (2/18, 11.11%).

The patients with intraperitoneal lymphadenopathy would be at risk to have more complicated conditions than those with lymphadenopathy in other areas. 5 of 18 cases had complications, which were pancreatic cancer, paraneoplastic pemphigus and bronchiolitis obliterans, acute myeloid leukemia-M2, thyroid cancer, and bronchiolitis obliterans respectively. The locations of lymphadenopathy in the first 3 patients with complications were retroperitoneal and/or intraperitoneal.

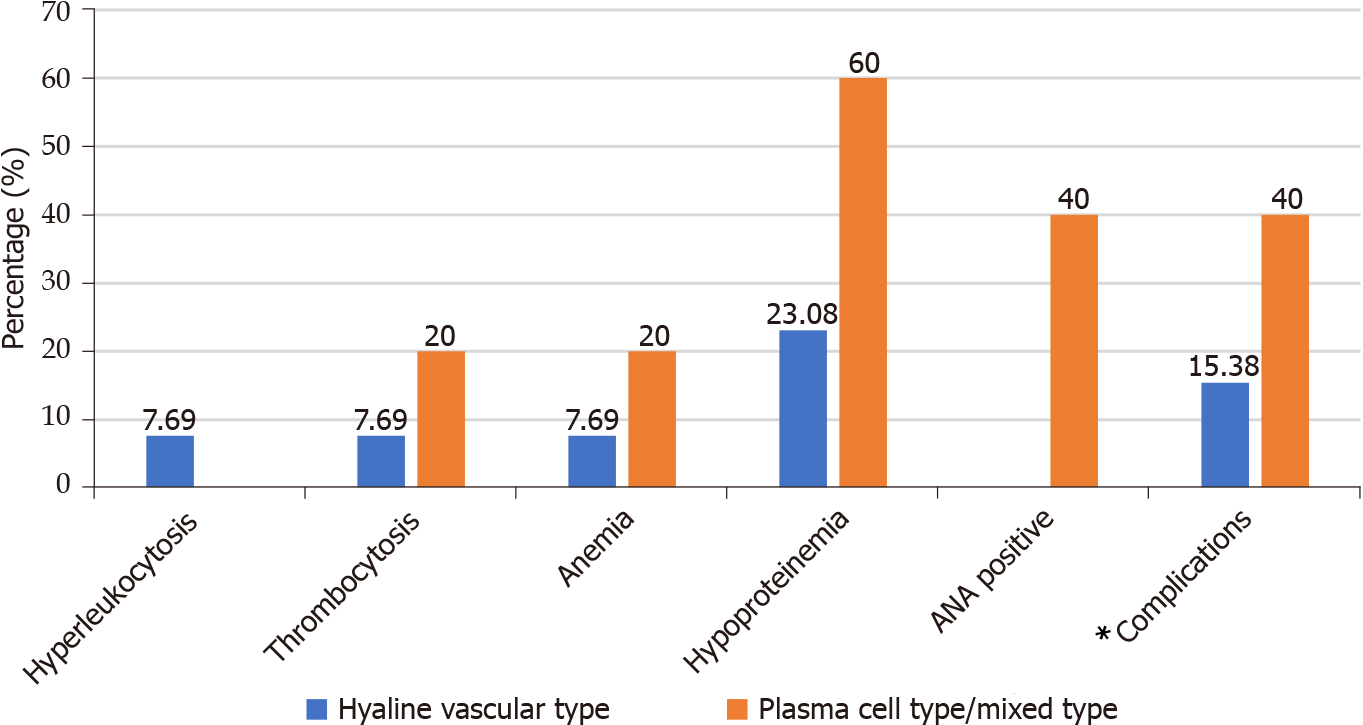

Because C-creative protein, direct antiglobulin test, interleukin (IL)-6, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were not tested in most cases, we hadn’t made statistical analysis for these indicators. All 18 patients underwent a lymph node biopsy. Most of them were hyaline vascular type (13/18, 72.22%), and a few were plasma cell type/mixed type (5/18, 27.78%). Compared with patients with hyaline vascular type, patients with plasma cell type/mixed-type UCD were more prone to have laboratory abnormalities and complications, as shown in Figure 2.

Most patients with iMCD (18/21, 85.71%) had a fever, and fever was the first symptom in 15 patients (71.43%). Skin complications (10/39, 25.64%) were recorded in the course of 9 cases diagnosed with iMCD, including red papules (7/21, 33.33%) which were often treated as an allergy, mouth ulcer or skin blisters at hand which were diagnosed with paraneoplastic pemphigus (2/21, 4.76%). Kidney involvement was common, and most patients showed positive urine protein and/or occult blood (14/21, 66.67%), among which three cases had massive proteinuria (urine protein level more than 2 g in 24 h). The creatinine levels increased in 9 cases, of which two patients were treated with renal replacement therapy and the other seven patients had an slight and transient elevation of creatinine level.

By analyzing the clinical manifestations of patients with iMCD, we found that the triad of thrombocytopenia, anasarca (polyserositis and edema) and renal insufficiency, which were exactly the core components of TAFRO syndrome, often occurred at the same time or in succession in the same patient. The correlations between two variables of the triad were verified by Fisher's exact probability method (P < 0.05). 8 patients finally met the diagnostic criteria of TAFRO syndrome proposed by Masaki et al.

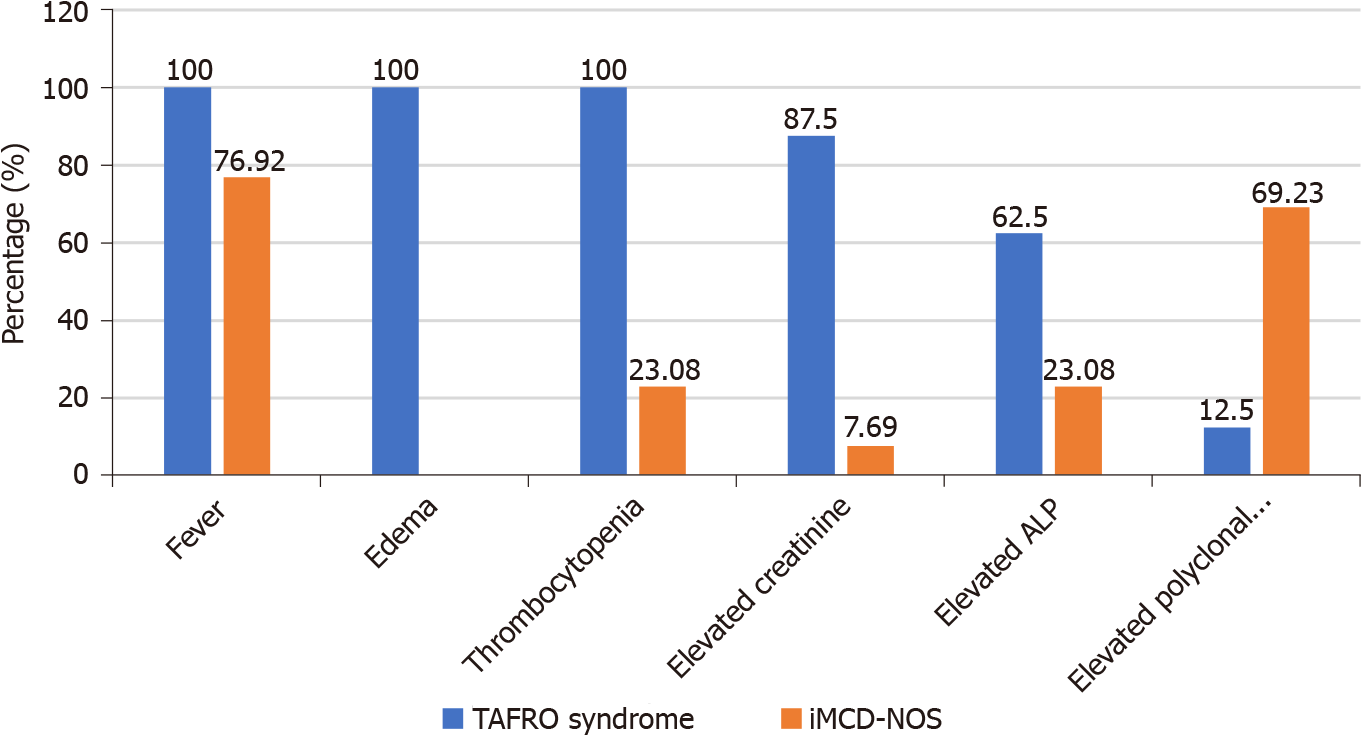

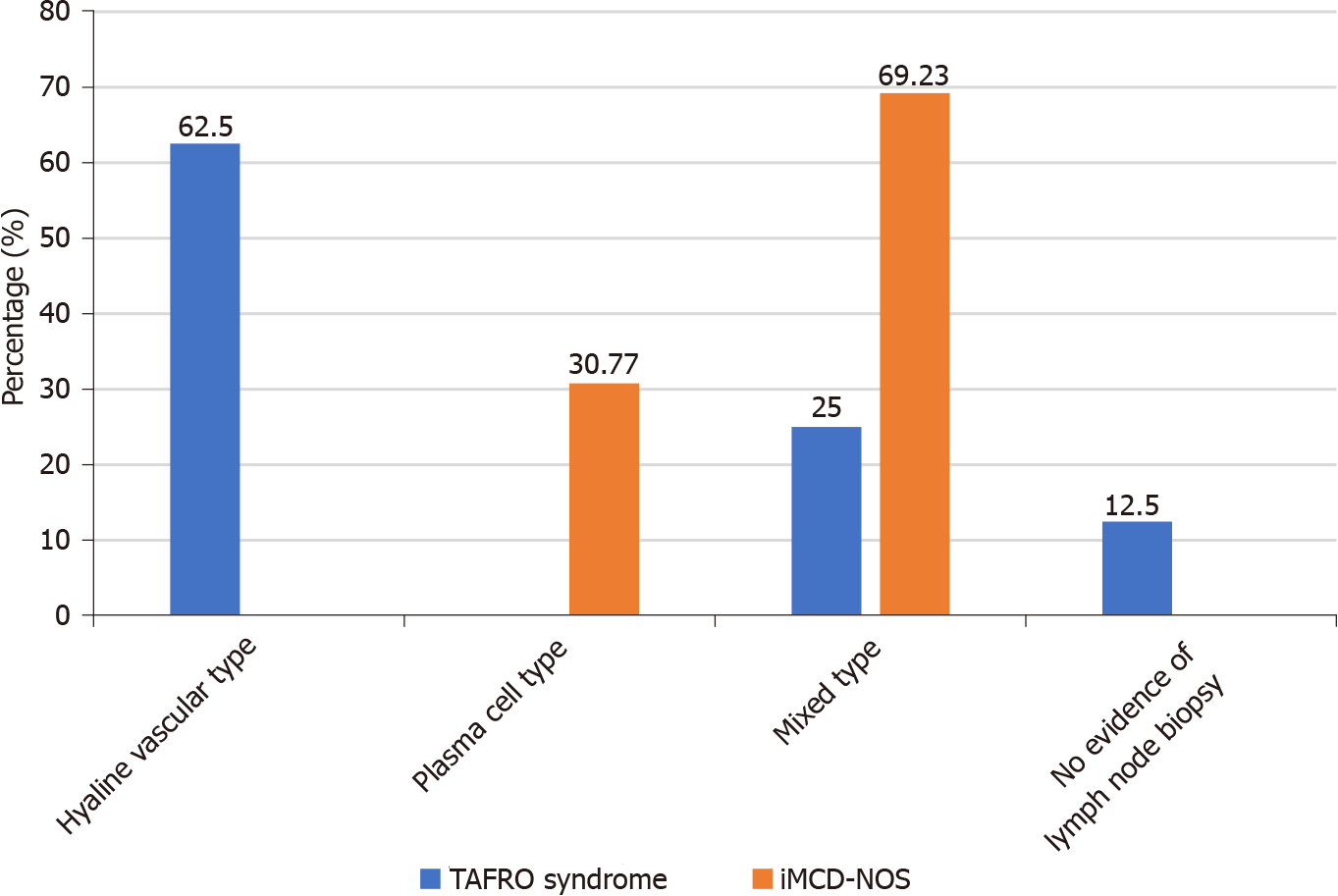

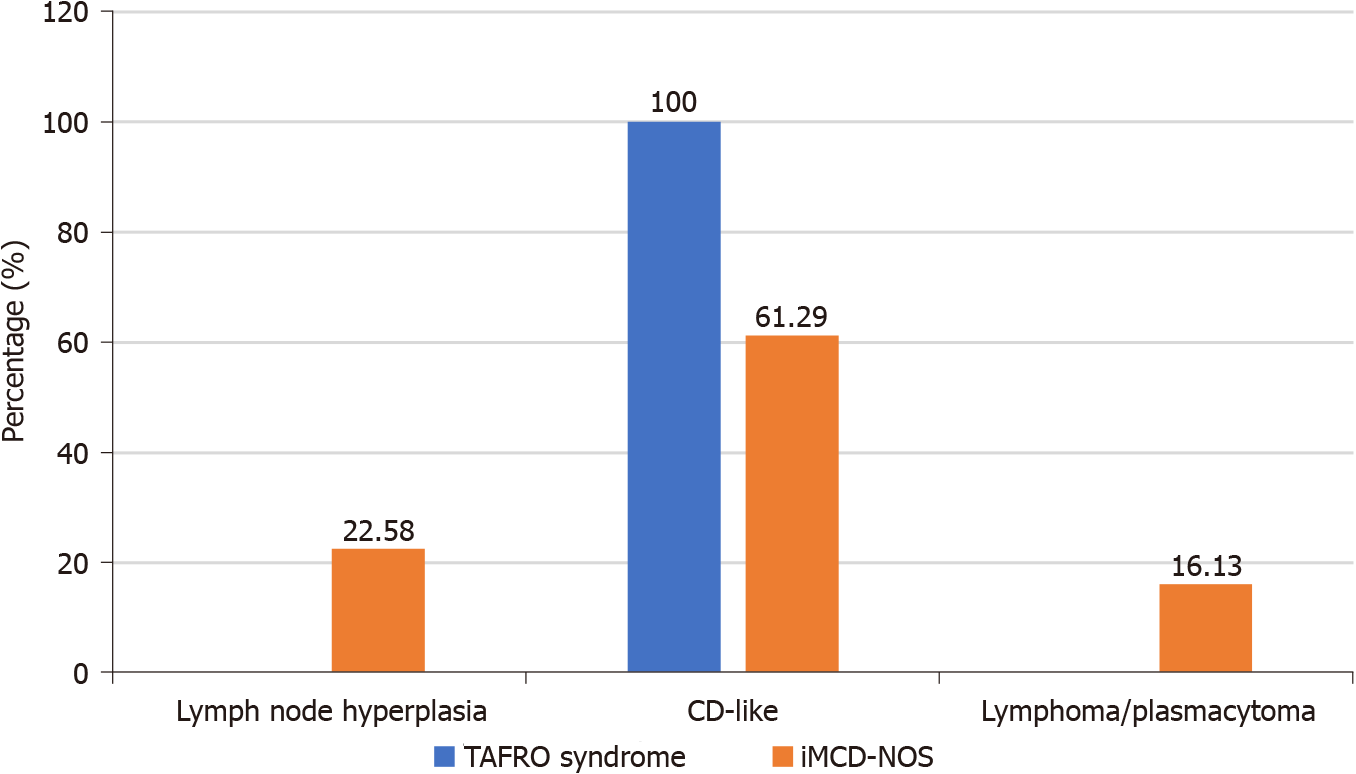

The clinical data and the diagnosis process of patients with TAFRO syndrome or iMCD-NOS were compared (Table 1 and Figures 3-5): (1) IL-6 and VEGF levels: Patients in iMCD-NOS group were more likely to show higher levels of IL-6 in blood than those with TAFRO syndrome because of the higher average rank of serum IL-6 Levels in iMCD-NOS group (P < 0.05).Because blood VEGF level was not a routine test in our hospital, so the records of serum VEGF levels only could be found in five patients diagnosed with TAFRO syndrome, all of the five patients showed significantly elevated serum VEGF levels (four cases > 800 pg/mL, one case 231.47 pg/mL); (2) Diagnosis process: The median time interval from onset to diagnosis in iMCD-NOS group was significantly prolonged than that in TAFRO syndrome group. In TAFRO syndrome group, except for one patient who rejected the suggestion of lymph node biopsy and renal biopsy at 1 mo after the onset of his symptoms; the other seven patients were all diagnosed within 1 to 1.5 mo after the onset of their symptoms. Among patients with iMCD-NOS, the median interval from the onset of their symptoms to the diagnosis of CD was 12 mo with the minimum and maxmum being 1 mo and 4 years respectively. The average time of lymph node biopsies and pathological consultations of iMCD-NOS group (1.69 and 2.38, respectively) were more than those of TAFRO syndrome group (1 and 1.375, respectively) (P < 0.05), and the poor consistencies of consultations were more likely happened in iMCD-NOS group (Figure 5).

Renal biopsies were performed in three patients who were diagnosed with TAFRO syndrome. Those findings of biopsies of lymph nodes and renal were thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) and hyalin vascular type, TMA and absence, and membrano proliferative glomerulonephritis and mixed type, respectively.

The study of CD has gone through the following stages: naming of CD for the first time[1]-the discovery of plasma cell type[2]–the discovery of MCD[3]–recognition of HIV as one of the causes of MCD[16,17]–proposal of the concept of iMCD[18]–proposal of the concept of TAFRO syndrome[8]. Although more than 60 years have passed since CD was proposed, the understanding of CD is still in the exploratory stage. What is the nature of CD? What are the internal relations and differences between different clinical and pathological types of CD? Can UCD tranform into MCD? TAFRO syndrome is a special subtype of iMCD? Or is it just a new special group whose clinical manifestations overlap with iMCD and are different from iMCD? The aforementioned problems are the focus of discussion in our study.

UCD and MCD are significantly different in clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis. However, these two clinical types are not completely independent: (1) There is an intermediate situation existing between single lymph node enlargement and multicentric lymph node enlargement, that is, multiple lymph node enlargement in a single region. At present, the latter is still classified as UCD, but what we need to think about is whether this single-region multiple lymph node enlargement is an intermediate or transitional state between single lymph node enlargement and multicenter lymph node enlargement. Oksenhendler et al[19] compared 38 cases of UCD with single lymph node enlargement and 19 cases of UCD with multiple lymph node enlargement in a single center. The results showed that five cases with fever and two cases with death all distributed in the latter; (2) UCD may be the early stage of MCD: Two patients diagnosed with MCD were enrolled in our study that were diagnosed with UCD and underwent surgical resection in their past history. Therefore, for patients diagnosed with UCD, the scan of systemic lymph nodes and the careful following-up should be necessary to rule out MCD; (3) Some clinical manifestations of UCD and iMCD overlap, such as PNP and ANA positive, which also suggests that UCD and iMCD are not completely independent[20].

The pathological types of CD, namely hyalin vascular type and plasma cell type, are not completely independent too. Typical hyalin vascular type and plasma cell type are two extremes of a pathological spectrum consistent with a CD, which are characterized by hyalinization of small blood vessels and interfollicular plasmacytosis respectively. However many patients may show mixed characteristics, that is mixed type. Patients with hyaline vascular type usually could have a definite diagnosis according to its specific morphology. Nevertheless, plasma cell type is not a specific morphological feature of CD. Many diseases, such as autoimmune diseases (SLE and IgG4-related diseases), POEMS syndrome, plasma cell tumor, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, all can show pathological features similar with plasma cell type of CD. Therefore, the diagnosis of CD of plasma cell type must require the combination of clinical and pathology[21,22]. Our study also showed that the patients with iMCD-NOS usually lacked specific clinical manifestations, and their lymph node pathology often needed to be differentiated from reactive lymph node hyperplasia and plasmacytoma /Lymphoma, which led to a significantly longer time interval from onset to diagnosis and a less consistency of diagnosis from different institution than those with TAFRO syndrome.

TAFRO syndrome was first proposed as a special subtype of iMCD[8]. The patients with TAFRO syndrome usually showed a group of similar clinical features which included thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, systemic edema and polyserous cavity effusion. Compared with those with iMCD-NOS, they were more likely to have a more acute course of disease, a worse general condition at the time of onset, smaller lymph nodes, not-elevated blood immunoglobulin levels, lower IL-6 levels in the serum, and higher levels of VEGF in the serum[11]. The lymph node pathology of patients with TAFRO syndrome reported in the literature was usually hyaline vascular type or mixed type, while the pathology of patients with iMCD-NOS was usually plasma cell type[13,23]. At present, the most authoritative diagnostic criteria for TAFRO syndrome are the Iwaki’s criteria and the Masaki’s criteria. These two diagnostic criteria have divergence on whether the pathological feature of lymph node in conformity with CD being necessary of diagnosis. Iwaki et al[11] advocated that TAFRO syndrome should be classified as a special subtype of iMCD, and pathological compliance with CD should be a necessary part of diagnosis of TAFRO syndrome. In Iwaki’s criteria, the pathological features of lymph node of patients with TAFRO syndrome were defined as atrophy of the germinal center with enlargement of endothelial cell nucleus, proliferation of interfollicular endothelial vein, and rare mature plasma cells. Masaki et al[13,14] believed that the clinical manifestations of patients with TAFRO syndrome were quite different from those with iMCD, so they advocated that TAFRO syndrome might be a special group that overlapped with iMCD but was different from iMCD. In Masaki’s criteria, pathological feature of lymph node was only regarded as one of the four secondary criteria rather than an essential part of diagnosis. Their explanation was that biopsy of lymph node might be unachievable for some patients due to anasarca, bleeding tendency or the smallness of the target lymph node, however early diagnosis and appropriate treatment without delay would be essential for favorable outcomes. We don’t think the two diagnostic criteria are in conflict in essence. The pathological features of patients with TAFRO syndrome reported by Masaki et al[13] were consistent with those reported by Iwaki et al[11]. Masaki et al[13] reported that the pathological classifications of most patients with TAFRO syndrome were mixed type, and a few were hyaline vascular type. Our study also confirmed that the special clinical manifestations of patients with TAFRO syndrome were determined by their pathological features. In our study, we screened patients whose clinical characteristics were in conformity with the definition of TAFRO syndrome (thrombocytopenia, multiple serosal effusion/edema, and renal insufficiency). The results showed that the pathological types of lymph nodes of 7 patients with TAFRO syndrome whose pathology of lymph nodes were achievable were as hyaline vascular type (5/8, 62.5%) and mixed type (2/8, 25%).

Except the role of pathological features, there are two other differences between Iwaki’s criteria and Masaki’s criteria which are gamma globulinemia and renal insufficiency. The level of gamma globulin in the serum being not-elevated was regarded as one major category in Iwaki’s criteria but was not mentioned in Masaki’s criteria. On the contrary, progressive renal insufficiency was regarded as one minor category in Masaki’s criteria as with pathological features but while was not mentioned in Iwaki’s criteria. We advocate that whether patients be diagnosed with TAFRO syndrome should be based on the combination of clinical manifestations and pathological features of patients, and the focus should be on the nature of the syndrome rather than be confined to a specific diagnosis item. In the series of TAFRO syndrome cases of our study, one patient was diagnosed according to his massive proteinuria and TMA feature of renal biopsy although biopsy of lymph node was absent. Another patient was diagnosed according to his typical clinical manifestations (thrombocytopenia, renal dysfunction, anasarca and polyserous cavity effusion) and pathological feature of lymph node being hyaline vascular type although the polyclonal gamma globulin level was slightly elevated.

The present study has several obvious limitations. First, it was a retrospective study and some laboratory data were not available. Second, A bias is inevitable because the CD patient population come from a single medical centre and the sample size is small. Despite these limitations, this study provides a useful panoramic view of CD and attempt to probe into the internal relationship between various types of CD.

In conclusion, the etiology and pathogenesis of both CD and TAFRO syndrome remain unclear. Further clinical and pathophysiological evidence are necessary for understanding this new entity. At the same time, clinicians, especially non-hematology specialists, should pay more attention to this entity and improve the awareness of diagnosis.

Castleman disease (CD) and TAFRO syndrome are very rare in clinical practice. Most clinicians, especially non-hematological clinicians, do not know enough about the two diseases, so it often leads to misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis.

What is the nature of CD? What are the internal relations and differences between different clinical and pathological types of CD? Can unicentric Castleman disease (UCD) transform into multicentric Castleman disease (MCD)? TAFRO syndrome is a special subtype of idiopathic MCD (iMCD)? Or is it just a new special group whose clinical manifestations overlap with iMCD and are different from iMCD? The aforementioned problems are the research motivation of our study.

This study aimed to explore the clinical features and diagnosis of CD and TAFRO syndrome.

We retrospectively collected the clinical and laboratory data of 39 patients who were diagnosed with CD from a single medical center.

UCD and iMCD are significantly different in clinical manifestations, treatment, and prognosis. However, a few patients with MCD were diagnosed as UCD in their early stage. There was a correlation between two of Thrombocytopenia, anasarca and elevated creatinine, which were important components of TAFRO syndrome. In UCD group, the pathologies of lymph modes were mostly hyaline vascular type (13/18, 72.22%), however plasma cell type or mixed type could also appear. In iMCD-NOS group and TAFRO syndrome group, the pathologies of lymph mode shown polarity of plasma cell type and hyaline vascular type respectively. Compared with patients with TAFRO syndrome, patients with iMCD-NOS were diagnosed more difficultly.

The clinical and pathological types of CD are not completely separate, there is an intermediate situation or mixed characteristics between two ends of clinical and pathological types. The clinical manifestations of patients with CD are determined by their pathological type. TAFRO syndrome is a special subtype of iMCD with unique clinical manifestations.

In the future, further research should be carried out on the pathological manifestations of lymph nodes and kidneys in patients with CD and TAFRO syndrome.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Emergency medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Corte-Real A, Srivastava D S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Castleman B, Iverson L, Menendez VP. Localized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymoma. Cancer. 1956;9:822-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Flendrig J, Schillings P. Benign giant lymphoma: the clinical signs and symptoms and the morphological aspectsy. Folia Med Neerl. 1969;12:119-120. |

| 3. | Frizzera G, Banks PM, Massarelli G, Rosai J. A systemic lymphoproliferative disorder with morphologic features of Castleman's disease. Pathological findings in 15 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:211-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weisenburger DD, Nathwani BN, Winberg CD, Rappaport H. Multicentric angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia: a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:162-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kojima M, Nakamura S, Shimizu K, Itoh H, Yamane Y, Murayama K, Tanaka H, Sugihara S, Shimano S, Sakata N, Masawa N. Clinical implication of idiopathic plasmacytic lymphadenopathy with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia: a report of 16 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kojima M, Nakamura S, Nishikawa M, Itoh H, Miyawaki S, Masawa N. Idiopathic multicentric Castleman's disease. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of five cases. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;201:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kojima M, Nakamura N, Tsukamoto N, Otuski Y, Shimizu K, Itoh H, Kobayashi S, Kobayashi H, Murase T, Masawa N, Kashimura M, Nakamura S. Clinical implications of idiopathic multicentric castleman disease among Japanese: a report of 28 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;16:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takai K, Nikkuni K, Shibuya H, Hashidate H. [Thrombocytopenia with mild bone marrow fibrosis accompanied by fever, pleural effusion, ascites and hepatosplenomegaly]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2010;51:320-325. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kawabata H, Takai K, Kojima M, Nakamura N, Aoki S, Nakamura S, Kinoshita T, Masaki Y. Castleman-Kojima disease (TAFRO syndrome) : a novel systemic inflammatory disease characterized by a constellation of symptoms, namely, thrombocytopenia, ascites (anasarca), microcytic anemia, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organomegaly : a status report and summary of Fukushima (6 June, 2012) and Nagoya meetings (22 September, 2012). J Clin Exp Hematop. 2013;53:57-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carbone A, Pantanowitz L. TAFRO syndrome: An atypical variant of KSHV-negative multicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:171-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iwaki N, Fajgenbaum DC, Nabel CS, Gion Y, Kondo E, Kawano M, Masunari T, Yoshida I, Moro H, Nikkuni K, Takai K, Matsue K, Kurosawa M, Hagihara M, Saito A, Okamoto M, Yokota K, Hiraiwa S, Nakamura N, Nakao S, Yoshino T, Sato Y. Clinicopathologic analysis of TAFRO syndrome demonstrates a distinct subtype of HHV-8-negative multicentric Castleman disease. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:220-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coutier F, Meaux Ruault N, Crepin T, Bouiller K, Gil H, Humbert S, Bedgedjian I, Magy-Bertrand N. A comparison of TAFRO syndrome between Japanese and non-Japanese cases: a case report and literature review. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Masaki Y, Kawabata H, Takai K, Kojima M, Tsukamoto N, Ishigaki Y, Kurose N, Ide M, Murakami J, Nara K, Yamamoto H, Ozawa Y, Takahashi H, Miura K, Miyauchi T, Yoshida S, Momoi A, Awano N, Ikushima S, Ohta Y, Furuta N, Fujimoto S, Kawanami H, Sakai T, Kawanami T, Fujita Y, Fukushima T, Nakamura S, Kinoshita T, Aoki S. Proposed diagnostic criteria, disease severity classification and treatment strategy for TAFRO syndrome, 2015 version. Int J Hematol. 2016;103:686-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Masaki Y, Kawabata H, Takai K, Tsukamoto N, Fujimoto S, Ishigaki Y, Kurose N, Miura K, Nakamura S, Aoki S; Japanese TAFRO Syndrome Research Team. 2019 Updated diagnostic criteria and disease severity classification for TAFRO syndrome. Int J Hematol. 2020;111:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou Q, Zhang Y, Zhou G, Zhu J. Kidney biopsy findings in two patients with TAFRO syndrome: case presentations and review of the literature. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lowenthal DA, Filippa DA, Richardson ME, Bertoni M, Straus DJ. Generalized lymphadenopathy with morphologic features of Castleman's disease in an HIV-positive man. Cancer. 1987;60:2454-2458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oksenhendler E, Duarte M, Soulier J, Cacoub P, Welker Y, Cadranel J, Cazals-Hatem D, Autran B, Clauvel JP, Raphael M. Multicentric Castleman's disease in HIV infection: a clinical and pathological study of 20 patients. AIDS. 1996;10:61-67. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Fajgenbaum DC, van Rhee F, Nabel CS. HHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapy. Blood. 2014;123:2924-2933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oksenhendler E, Boutboul D, Fajgenbaum D, Mirouse A, Fieschi C, Malphettes M, Vercellino L, Meignin V, Gérard L, Galicier L. The full spectrum of Castleman disease: 273 patients studied over 20 years. Br J Haematol. 2018;180:206-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jia N, Ping L, Rengui W, Liangchun W, Wanzhong Z. Clinicopathological Observation of Castleman's Disease. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2003;32:521-524. |

| 21. | Yong L, Guozhang C. Suggestions on Diagnostic Criteria of Castleman's Disease. Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2013;42:644-647. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Frizzera G. Atypical lymphoproliferative disorders. In: Knowles D. Neoplastic Hematopathology. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2000: 569-622. |

| 23. | Srkalovic G, Marijanovic I, Srkalovic MB, Fajgenbaum DC. TAFRO syndrome: New subtype of idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2017;17:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |