Published online Feb 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1485

Peer-review started: July 10, 2021

First decision: November 8, 2021

Revised: November 8, 2021

Accepted: January 6, 2022

Article in press: January 6, 2022

Published online: February 16, 2022

Processing time: 215 Days and 13.3 Hours

Cancer survivors have a higher risk of developing secondary cancer, with pre

To describe the features and clinical significance of a prior malignancy in patients with gastric cancer (GC).

We identified eligible patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, and compared the clinical features of GC patients with/without prior cancer. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox analyses were used to assess the prognostic impact of prior cancer on overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS) outcomes. We also validated our results in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort and compared mutation patterns.

In the SEER dataset, of the 35492 patients newly diagnosed with GC between 2004 and 2011, 4,001 (11.3%) had at least one prior cancer, including 576 (1.62%) patients with multiple cancers. Patients with a prior cancer history tended to be elderly, with a more localized stage and less positive lymph nodes. The prostate (32%) was the most common initial cancer site. The median interval from initial cancer diagnosis to secondary GC was 68 mo. By using multivariable Cox analyses, we found that a prior cancer history was not significantly associated with OS (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.01, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.97–1.05). However, a prior cancer history was significantly associated with better GC-specific survival (HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.78–0.85). In TCGA cohort, no significant difference in OS was observed for GC patients with or without prior cancer. Also, no significant differences in somatic mutations were observed between groups.

The prognosis of GC patients with previous diagnosis of cancer was not inferior to that of primary GC patients.

Core Tip: We identified eligible cases during 2004-2011 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database and compared the clinical features of gastric cancer (GC) patients with/without prior cancer. We found that patients with a history of prior cancer tended to be elderly, with a more localized stage and less positive lymph nodes. The prognosis of GC patients with diagnosis of prior cancer was not inferior to primary GC.

- Citation: Yin X, He XK, Wu LY, Yan SX. Effect of prior malignancy on the prognosis of gastric cancer and somatic mutation. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(5): 1485-1497

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i5/1485.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i5.1485

With the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori and healthier lifestyles, gastric cancer (GC) incidence and mortality have steadily declined in the United States[1,2]. In recent decades, thanks to active cancer screening and effective therapies, many cancer survivors now enjoy relatively longer lives. Although risk factors for primary GC incidence and prognosis are well documented[2,3], little is known about secondary GC occurrence in cancer survivors.

With the increasing aging populations, it is anticipated that the prevalence of secondary cancer in cancer survivors will increase[4]. A recent study revealed that approximately 17.8% of elderly (≥ 65 years) and 7.3% of young adults (< 65 years) with newly diagnosed GC have a prior cancer history[5].

Due to inadequate selection criteria, patients with prior cancers are routinely excluded from oncology clinical trials[5,6]; thus, a substantial number of patients may have lost access to cutting-edge therapies and care. The impact of prior cancer on a current malignancy is often inconsistent and varies by cancer type (e.g., pancreatic, prostate, esophageal, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, gastrointestinal, and lung cancers)[7-16]. To the best of our knowledge, there is a dearth of data on the characteristics and survival outcomes of GC patients with prior cancer. Similarly, there is a lack of real-world evidence to address these issues.

In this study, we characterized GC patients with a prior cancer history and estimated survival outcomes from real-world data. Understanding the prognostic impact of prior cancer on GC patients may have significant implications for improved therapeutic strategies and surveillance.

We identified eligible patients with newly diagnosed and histopathologically proven GC between 2004 and 2011 in 18 Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries (https://seer.cancer.gov/), which covered approximately 30% of the United States population[17]. We included patients aged ≥ 18 with active follow-up to the end of 2014. Tumor 83 site codes (C16.0, C16.1, C16.2, C16.3, C16.4, C16.5, C16.6, C16.8, and C16.9) were used for GC identification according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology 3rd edition. A sequence number was used to identify the number of multiple primaries. A sequence number = 0 indicated that an individual had only one primary cancer, and a larger number indicated more than one primary cancer. To reduce the possibility of misclassifying synchronous metastases, a latency period of at least 6 mo was required from initial prior cancer diagnosis to secondary GC. For initial prior cancer, we excluded cases termed as GC. We categorized prior malignancies of interest including prostate, gastrointestinal, hematologic, breast, genitourinary, and lung cancers.

The following information was collected from the SEER database: age, sex, race, marital status, tumor sites for the prior malignancy and GC, lymph nodes examined, positive lymph nodes, SEER stage, GC grade, and current and prior cancer therapies. To validate the impact of prior cancer on GC patient survival, we used The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database as an external validation source. Primary gastric adenocarcinoma in TCGA with or without prior malignancy was included. Clinicopathological and genomic data were also queried in TCGA database.

Baseline characteristics from GC patients with or without prior cancer were summarized and investigated using the χ2 test. For patients with prior cancer, site distribution, stages, and main therapies were classified. To investigate the impact of a prior cancer, we calculated overall GC survival and cancer-specific 3-year survival rates with and without prior cancer, stratified by age. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed for patients with and without prior cancer, and survival differences were examined using the log-rank test. Furthermore, to validate our results, we adopted a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model to estimate hazard ratios (HRs). Using the maftools package in R, the frequency and visualization of gene mutations in TCGA was performed. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in TCGA samples, with and without prior malignancy, were analyzed using the Limma package. DEGs were considered genes where fold change > 2 and aP < 0.05. All P values were two-sided and statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) and R software version 3.40 (www.r-project.org).

In the SEER dataset, from 2004 to 2011, 35492 patients were identified with newly diagnosed GC, of which, 4,001 (11.27%) had one or more prior malignancy, including 576 (1.62%) patients with multiple malignancies. Baseline patient demographic and clinicopathological characteristics are described in Table 1. When compared with patients with primary GC only, those with a history of prior cancer were more likely to be elderly, male, white, and married. The proportion of cancers arising at cardia and fundus sites, with negative lymph nodes, at a localized stage, and with well/moderate differentiation, were higher in patients with prior cancer. In terms of GC therapeutic options, no significant differences were observed in the percentage of surgeries. In patients without prior cancer, radiotherapy and chemotherapy were more common. From TCGA dataset, 13 patients had one or more prior malignancy and 376 patients had no prior malignancy.

| Characteristics | No previous cancer, n = 31491 (88.73%) | With prior cancer, n = 4001 (11.27%) | P value | ||

| Age (yr) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 65 | 13160 | (41.79%) | 714 | (17.85%) | |

| ≥ 65 | 18331 | (58.21%) | 3287 | (82.15%) | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 19479 | (61.86%) | 2777 | (69.41%) | |

| Female | 12012 | (38.14%) | 1224 | (30.59%) | |

| Race | < 0.001 | ||||

| White | 22087 | (70.14%) | 2926 | (73.13%) | |

| Black | 4090 | (12.99%) | 555 | (13.87%) | |

| AI/AN | 285 | (0.91%) | 16 | (0.4%) | |

| AP | 4898 | (15.55%) | 504 | (12.6%) | |

| Unknown | 131 | (0.42%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Marital status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Married | 17571 | (55.80%) | 2366 | (59.14%) | |

| Unmarried | 12473 | (39.61%) | 1416 | (35.39%) | |

| Unknown | 1447 | (4.59%) | 219 | (5.47%) | |

| Site | |||||

| Cardia and Fundus | 10537 | (33.46%) | 1486 | (37.14%) | |

| Body of stomach | 6340 | (20.13%) | 844 | (21.09%) | |

| Antrum and Pylorus | 7370 | (23.40%) | 862 | (21.54%) | |

| Stomach, NOS | 7244 | (23.00%) | 809 | (20.22%) | |

| Lymph nodes examined | < 0.001 | ||||

| No examined | 16884 | (53.62%) | 2287 | (57.16%) | |

| 1-15 | 7020 | (22.29%) | 909 | (22.72%) | |

| ≥ 16 | 6338 | (20.13%) | 686 | (17.15%) | |

| Unknown | 1249 | (3.97%) | 119 | (2.97%) | |

| Positive lymph nodes | < 0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 4914 | (36.79%) | 693 | (43.45%) | |

| 1-2 | 2599 | (19.46%) | 327 | (20.50%) | |

| 3-6 | 2399 | (17.96%) | 276 | (17.30%) | |

| 7-15 | 2355 | (17.63%) | 207 | (12.98%) | |

| ≥ 16 | 1066 | (7.98%) | 89 | (5.58%) | |

| Unknown | 25 | (0.19%) | 3 | (0.19%) | |

| SEER stage | < 0.001 | ||||

| Localized | 7209 | (22.89%) | 1190 | (29.74%) | |

| Regional | 8978 | (28.51%) | 1051 | (26.27%) | |

| Distant | 12615 | (40.06%) | 1242 | (31.04%) | |

| Unstaged | 2689 | (8.54%) | 518 | (12.95%) | |

| Grade | < 0.001 | ||||

| G1 | 1087 | (3.45%) | 181 | (4.52%) | |

| G2 | 7012 | (22.27%) | 1027 | (25.67%) | |

| G3 | 18112 | (57.51%) | 2108 | (52.69%) | |

| G4 | 567 | (1.80%) | 68 | (1.70%) | |

| Unknown | 4713 | (14.97%) | 617 | (15.42%) | |

| Surgery | 0.088 | ||||

| No | 16692 | (53.01%) | 2194 | (54.84%) | |

| Yes | 14630 | (46.46%) | 1785 | (44.61%) | |

| Unknown | 169 | (0.54%) | 22 | (0.55%) | |

| Radiation | < 0.001 | ||||

| None | 23413 | (74.35 %) | 3098 | (77.43%) | |

| Radiation | 7789 | (24.73%) | 866 | (21.64%) | |

| Unknown | 289 | (0.92%) | 37 | (0.92%) | |

| Chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||||

| No/Known | 17189 | (54.58%) | 2569 | (64.21%) | |

| Chemotherapy | 14302 | (45.42%) | 1432 | (35.79%) | |

Regarding initial cancer sites, the prostate (32%) was the most common site, followed by gastrointestinal tract (17%), genitourinary (15%), breast (14%), others (10%), hematological system (7%), and the lung (5%) (Figure 1A). Unsurprisingly, the majority of prior cancers were either at localized (37%) or localized/regional stages (28%), with only 5% at distant stages (Figure 1B). Regarding therapeutic options for initial cancers, surgery was the most common modality, with most cases receiving multiple therapies (Figure 1C). The median time of initial malignancy to the time of subsequent GC diagnosis varied across initial cancer sites (from 50-78 mo, average = 68 mo; Supplementary Table 1). For breast and genitourinary cancer survivors, this interval exceeded 68 mo, whereas it was only 50 mo for lung cancer survivors.

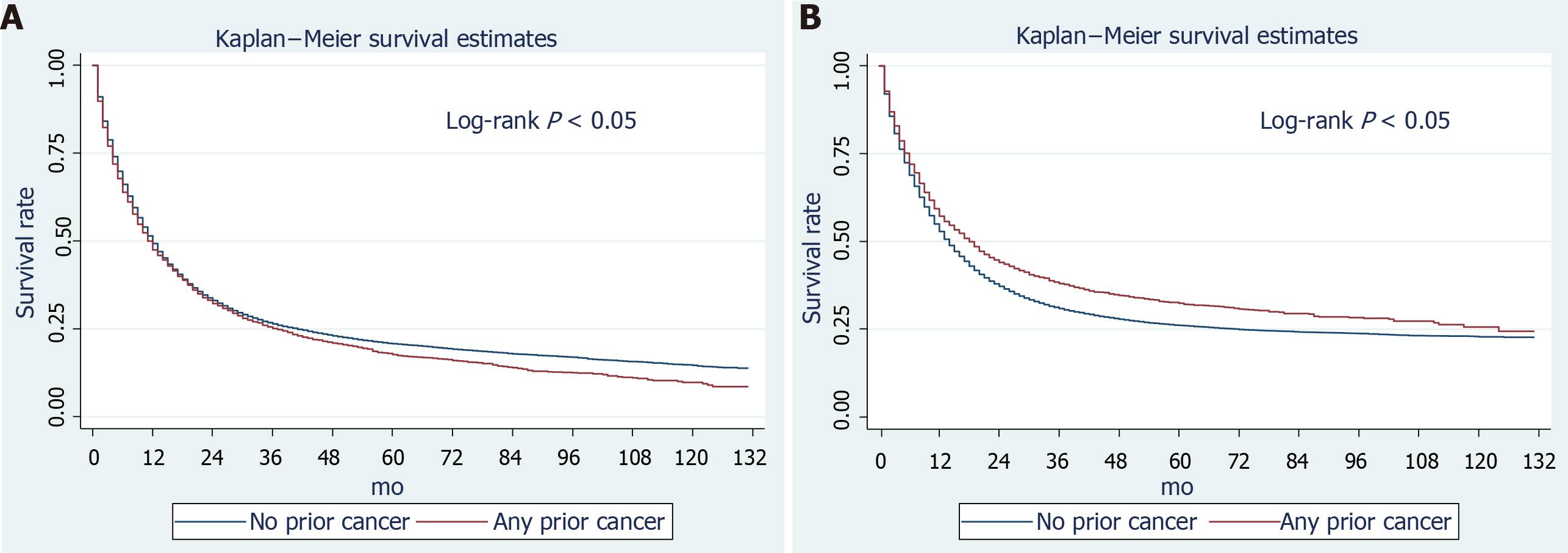

Among the primary GC patients in the SEER dataset, 25,592 (81%) died and 22,223 (87%) GC-related deaths were recorded during follow-up. In GC patients with prior cancer, 3407 (85.28%) died, including 544 initial cancer-related deaths and 2,353 GC-related deaths (Supplementary Table 2). The all-cause and GC-specific 3-year survival rates of primary GC patients were 26.42% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 25.90%–26.94%) and 30.91% (95%CI: 30.34%–31.47%), respectively, while for patients with a history of prior cancer, theses rates were 25.20% (95%CI: 23.80%–26.63%) and 38.03 (95%CI: 36.27%–39.79%), respectively (Table 2, Supplementary Table 3). Thus, it appeared that patients with prior cancer had a higher GC-related survival rate. Considering age may have had a role, we calculated the survival rates stratified by age. In either young or elderly patients, a higher GC-specific survival rate was observed in those with prior cancer. In terms of different initial cancer sites, lung cancer survivors had lower all-cause and cancer-specific survival (CSS) rates than those with other initial cancer sites. From Kaplan-Meier curves, patients with prior cancer had a significantly worse overall-survival (OS) and better GC-specific survival rate (log-rank tests both P < 0.05) (Figure 2). We also constructed multivariable Cox regression models to confirm the effects of prior cancer on survival outcomes. A history of previous malignancies was not independently associated with all-cause death (HR: 1.01, 95%CI: 0.97–1.05, P = 0.644) after adjusting for other variables (Table 3). By contrast, it was significantly associated with a superior GC-specific survival (HR: 0.82, 95%CI: 0.78–0.85, P < 0.001). When stratified by initial cancer site, a history of other malignancies was related to worse OS, with prior breast cancer associated with superior OS (Supplementary Table 4). For CSS, a history of prostate, gastrointestinal, hematological, breast, and lung cancers was associated with a better prognosis (Supplementary Table 4). To validate our results, we performed subgroup analyses stratified by age, tumor size, and stage. In both < 65 and ≥ 65 age groups, a prior cancer history was unrelated to OS and was associated with superior CSS (Table 4). For different GC stages, prior cancer had an inconsistent impact on OS (Table 4) and significantly increased the overall mortality risk of localized stage GC (HR = 1.10), whereas, it reduced the mortality risk of distant-stage GC (HR = 0.92). (Table 4) Consistently, prior cancer was an independent factor for GC-specific survival, regardless of stage (Table 4). The timing of prior cancer was unrelated to GC OS. However, the timing of a prior cancer was associated with a better GC-specific survival rate.

| Prior initial cancer site | All-cause survival (95%CI) | ||

| Overall | Age < 65 yr (%) | Age ≥ 65 yr (%) | |

| No prior cancer | 26.42 (25.90, 26.94) | 28.95 (28.14, 29.77) | 24.49 (23.82, 25.16) |

| With prior cancer | 25.20 (23.80, 26.63) | 30.12 (26.68, 33.62) | 24.08 (22.55, 25.65) |

| Prostate | 24.79 (21.39, 28.32) | 23.33 (16.23, 31.21) | 25.16 (21.35, 29.14) |

| Gastrointestinal | 26.47 (23.96, 29.04) | 31.13 (22.60, 40.03) | 26.00 (23.38, 28.68) |

| Hematologic | 28.06 (22.75, 33.58) | 42.17 (31.11, 52.80) | 22.16 (16.49, 28.38) |

| Breast | 26.80 (22.96, 30.78) | 33.27 (25.47, 41.25) | 24.36 (20.04, 28.92) |

| Genitourinary | 23.64 (20.14, 27.30) | 34.29 (25.39, 43.35) | 21.06 (17.36, 25.02) |

| Lung | 19.32 (13.87, 25.45) | 12.50 (3.95, 26.23) | 20.83 (14.64, 27.79) |

| Other | 22.90 (18.79, 27.26) | 24.61 (16.44, 33.66) | 22.33 (17.66, 27.35) |

| Characteristics | All-cause adjusted HR | P value | Cancer-specific adjusted HR | P value |

| Age (yr; vs < 65) | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 1.32 (1.28, 1.35) | < 0.001 | 1.25 (1.22, 1.29) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (vs male) | ||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.91, 0.96) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | < 0.001 |

| Race (vs white) | ||||

| Black | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.12) | < 0.001 |

| AI/AN | 1.14 (1.01, 1.29) | 0.033 | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32) | 0.023 |

| AP | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) | < 0.001 | 0.79 (0.76, 0.82) | < 0.001 |

| Marital status (vs married) | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.14 (1.12, 1.17) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.08, 1.14) | < 0.001 |

| Gastric cancer site (vs cardia and fundus) | ||||

| Body of stomach | 0.96 (0.92, 0.99) | 0.013 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Antrum and Pylorus | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.727 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01) | 0.114 |

| Lymph nodes examined (vs no examined) | ||||

| 1-15 | 0.73 (0.69, 0.77) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.68, 0.77) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 16 | 0.65 (0.61, 0.68) | < 0.001 | 0.66 (0.62, 0.71) | < 0.001 |

| Prior history of cancer (vs none) | ||||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 0.644 | 0.82 (0.78, 0.85) | < 0.001 |

| SEER stage (vs localized) | ||||

| Regional | 2.34 (2.26, 2.44) | < 0.001 | 2.83 (2.70, 2.96) | < 0.001 |

| Distant | 3.43 (3.31, 3.57) | < 0.001 | 4.35 (4.16, 4.54) | < 0.001 |

| Grade (vs G1) | ||||

| G2 | 1.19 (1.10, 1.28) | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.16, 1.38) | < 0.001 |

| G3 | 1.56 (1.45, 1.67) | < 0.001 | 1.75 (1.61, 1.91) | < 0.001 |

| G4 | 1.60 (1.43, 1.79) | < 0.001 | 1.85 (1.63, 2.09) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery (vs none) | ||||

| Yes | 0.45 (0.43, 0.48) | < 0.001 | 0.44 (0.42, 0.47) | < 0.001 |

| Radiation (vs none) | ||||

| Radiation | 0.92 (0.89, 0.95) | 0.007 | 0.92 (0.89, 0.96) | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy (vs none) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.52 (0.51, 0.54) | < 0.001 | 0.53 (0.51, 0.55) | < 0.001 |

| Characteristics | All-cause survival (CI) | P value | Gastric cancer-specific survival (CI) | P value |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 65 | 1.08 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.064 | 0.77 (0.69, 0.85) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 65 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.843 | 0.83 (0.79, 0.87) | < 0.001 |

| Stage | ||||

| Localized | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 0.012 | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Regional | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.777 | 0.84 (0.78, 0.92) | < 0.001 |

| Distant | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98) | 0.014 | 0.79 (0.73, 0.85) | < 0.001 |

| Timing of prior cancer | ||||

| < 5 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 0.275 | 0.77 (0.72, 0.82) | < 0.001 |

| 5-10 | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04) | 0.525 | 0.84 (0.78, 0.90) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 10 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 0.811 | 0.88 (0.81, 0.95) | 0.001 |

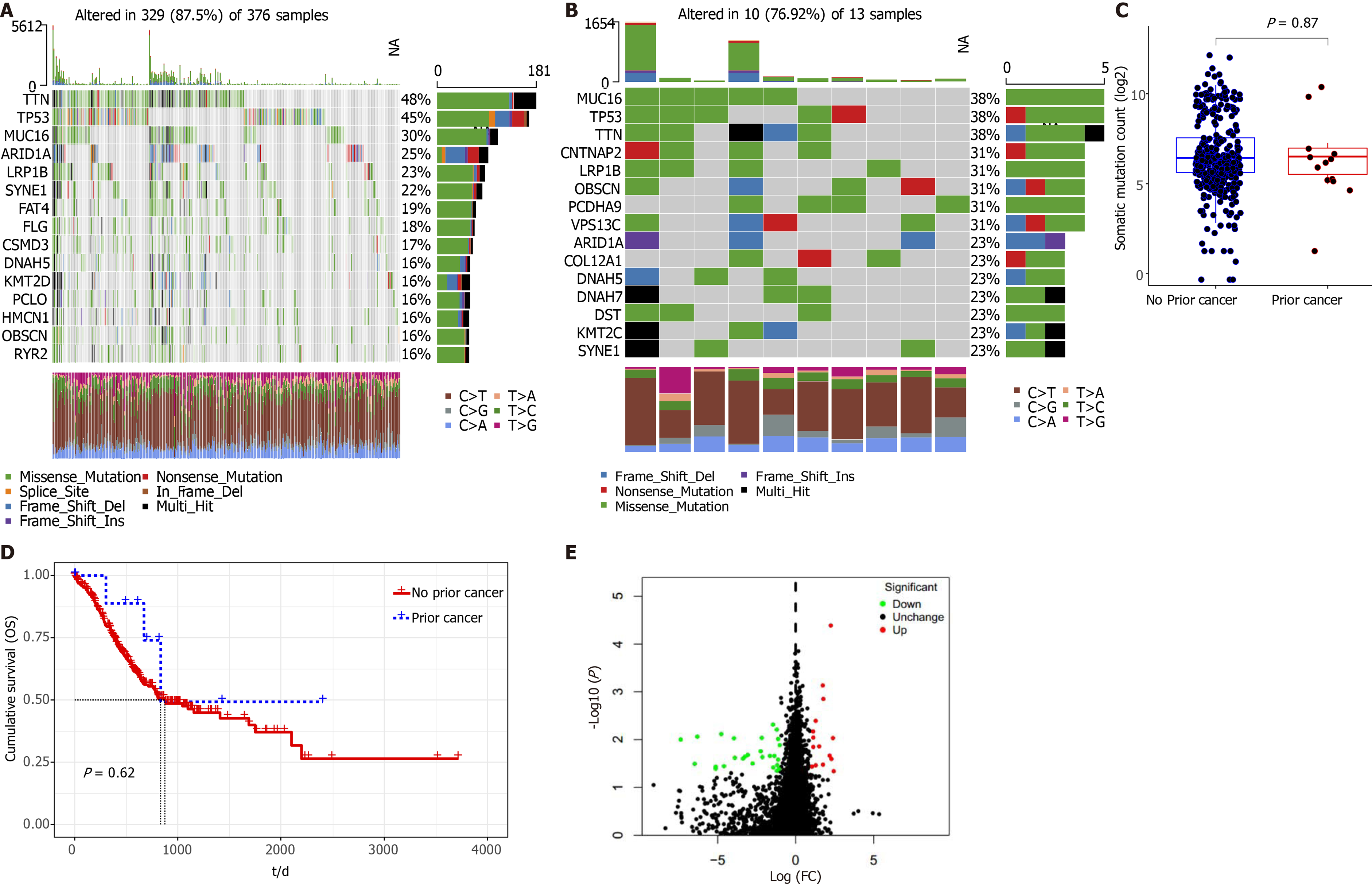

We observed that 329 patients (329/376, 87.5%) without prior cancer had molecular alterations; the top mutated genes were titin (TTN), tumor protein 53 (TP53), mucin 16 (MUC16), AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A, and lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1B (LRP1B) (Figure 3A). Ten patients (10/13, 76.92%) with prior cancer had molecular alterations; the top mutation genes were MUC16, TP53, TTN, contactin associated protein 2, and LRP1B (Figure 3B). We observed no significant differences in somatic mutations between GC patients with or without prior cancer (Figure 3C). Distinct to the SEER dataset, TCGA appeared to show a survival benefit toward patients with prior cancer. Due to insufficient sample numbers, we observed no significant OS between GC patients with or without prior cancer (Figure 3D). Also, we identified 42 DEGs between cancer groups, with 15 upregulated and 27 downregulated genes identified in the prior cancer group. Additionally, we constructed a volcano map (Figure 3E) to show the distribution of these 42 DEGs.

Cancer survivors are at higher risk of developing secondary malignancies[18,19]. With increasing numbers of cancer survivors having complicated dual or even multiple malignancies, the prognostic impact of previous cancer on cancer survival remains controversial. A pan-cancer study investigated the distinct effects of prior cancer across 20 cancer types[20]. For colorectal, sarcoma, melanoma, breast, cervical, endometrial, prostate, urothelial, orbital, and thyroid cancers, a prior cancer history contributed to a poor OS, while nasopharynx, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and brain cancer patients, with prior cancer, had a similar OS to patients without prior cancer[20]. In our population-based study, more than 10% of patients with newly diagnosed GC had a prior cancer history, similar to that reported by Murphy et al[5]. Newly diagnosed GC patients with prior cancer were older, suggesting that age is an independent risk factor for secondary malignancies[21]. The proportion of localized stages and negative lymph nodes were higher in patients with a prior cancer history, suggesting that cancer survivors may receive more active surveillance and that their cancer may be incidentally diagnosed at earlier stages[22,23]. Unsurprisingly, prostate cancer was the most common prior tumor type, suggesting an indolent clinical course. Similar results were identified for lung cancer patients[24]. The interval between initial malignancy and GC suggested the GC risk increased after five years of prior cancer diagnoses.

In oncology clinical trials, a substantial proportion of cancer survivors are excluded due to stringent eligibility criteria, and the assumption that these patients have inferior survival[6,24-27]. A previous study reported that the heterogeneous impact of a prior cancer history should be reconsidered according to the specific cancer type[20]. Thus, it is inappropriate to assume a prior cancer is a risk factor for mortality in a newly diagnosed cancer. In our study, using the SEER database, GC patients with a prior cancer history had similar 3-year survival rates compared to those without a prior cancer history. Despite a survival benefit trend, these data were not significant for patients with prior cancer.

A similar result was identified and validated in TCGA cohort, and suggested that a prior cancer history did not adversely affect the overall prognosis in GC patients. Regarding CSS, patients with prior cancer had superior GC-specific survival after particular variables were adjusted. It is unclear why a prior cancer history could improve GC-specific survival. Cancer survivors may undergo active cancer sur

In our study, we could not avoid bias as the percentage of early stage GC was more frequent in patients with prior cancer. However, we did not believe this bias was responsible for GC-specific survival advantages because a prior cancer was also associated with better GC-specific survival in the localized stages (HR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.74–0.91). We speculated that higher competing mortality risks (either due to prior cancer or other factors) in patients with prior cancer may have accounted for GC-specific survival benefits[31]. Further studies are required to address these observations.

In subgroup analyses, age did not affect the impact of a prior cancer diagnosis. A prior cancer had no significant influence on OS, but improved CSS in GC patients. We also noted that the prognostic impact of a prior cancer was independent of the time of previous cancer diagnosis, suggesting that GC patients with a prior cancer diagnosis could be considered for trial enrollment regardless of the time.

We observed that the impact of a prior cancer history on survival was varied across different cancer types. In 2009, Pulte et al[10] reported that non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with prior malignancies had worse prognoses than those without prior cancer. Youn et al[32] subsequently showed a reduced survival time for Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors with secondary gastrointestinal cancer. In contrast, opposite trends were identified in other studies: Smyth et al[11] showed that gastrointestinal cancer patients with/without prior cancer had comparable OS and gastrointestinal cancer-specific survival times. Also, in early or advanced lung cancer stages, no differences in OS were noted between patients with and without prior cancer[24,33]. Pruitt et al[24] demonstrated improved lung CSS outcomes in patients with prior cancer. For stage IV esophageal cancer, a prior malignancy had no impact on OS[9]. A recent study explored the prognostic effect landscape across 20 prior cancer types[20]. However, this study primarily focused on pan-cancer and did not characterize specific clinical features and the specific impact of GC with a prior cancer history. Thus, our study filled this knowledge gap.

Our study had several limitations. The SEER database did not provide detailed chemotherapy and radiation information, and the efficacy and tolerability of prior therapies were unclear. Other covariates, such as Helicobacter pylori infection status, genetic information, and comorbidities were unavailable. Also, we could not completely exclude the possibility of GC metastatic misclassifications from earlier tumors. Finally, our findings were based on the SEER database and TCGA cohorts, thereby limiting overall generalizability to other populations. Further studies or independent cohorts are required to validate our findings and conclusions.

In the SEER database, 11.3% of newly diagnosed GC patients had a prior cancer history, with GC occurring within 6 years after prior cancer diagnosis. GC patients with a prior cancer history had a non-inferior OS, and the CSS was slightly improved. We suggest that in future clinical trials, broader inclusion criteria for GC patients with previous cancer should be considered in order to obtain the best inclusion rate and generalizable results.

Cancer survivors had a higher risk of developing secondary cancer, and previous studies have indicated the heterogeneous effects of prior cancer on cancer survivors.

To evaluate prior malignancy on patients with gastric cancer (GC).

To describe the features and clinical significance of a prior malignancy on patients with GC.

We identified eligible cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and compared clinical features of GC patients with/without prior cancer. We adopted Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox analyses to assess the prognostic impact of a prior cancer on the overall survival (OS) and GC-specific survival outcomes. We also validated these results in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort and compared mutation patterns.

In the SEER dataset, 35,492 patients newly diagnosed with GC during 2004-2011, 4,001 (11.3%) cases had at least one prior cancer, including 576 (1.62%) cases with multiple prior cancers. Patients with a history of prior cancer tended to be elderly, with a more localized stage and less positive lymph nodes. Prostate (32%) was the most common initial cancer site. The median interval from the initial diagnosis of malignancy to secondary gastric cancer was 68 mo. A history of prior cancer was not significantly associated with overall (hazard ratio:1.01, 95% confidence interval: 0.97-1.05) survival in multivariable Cox analyses.

The prognosis for GC patients with a diagnosis of prior cancer was not inferior to primary GC patients.

The prognosis for GC patients with a diagnosis of prior cancer was not inferior to primary GC patients. Our results suggest that a wide range of conclusions should be considered in the clinical trials of GC patients with a previous cancer to obtain the best inclusion rate and generalizable results.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kotelevets SM S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Jim MA, Pinheiro PS, Carreira H, Espey DK, Wiggins CL, Weir HK. Stomach cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001-2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer. 2017;123 Suppl 24: 4994-5013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Karimi P, Islami F, Anandasabapathy S, Freedman ND, Kamangar F. Gastric cancer: descriptive epidemiology, risk factors, screening, and prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23: 700-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1159] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 120.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sitarz R, Skierucha M, Mielko J, Offerhaus GJA, Maciejewski R, Polkowski WP. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10: 239-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 743] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 103.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morrell S, Young J, Roder D. The burden of cancer on primary and secondary health care services before and after cancer diagnosis in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19: 431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Murphy CC, Gerber DE, Pruitt SL. Prevalence of Prior Cancer Among Persons Newly Diagnosed With Cancer: An Initial Report From the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4: 832-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim ES, Bernstein D, Hilsenbeck SG, Chung CH, Dicker AP, Ersek JL, Stein S, Khuri FR, Burgess E, Hunt K, Ivy P, Bruinooge SS, Meropol N, Schilsky RL. Modernizing Eligibility Criteria for Molecularly Driven Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33: 2815-2820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | He X, Li Y, Su T, Lai S, Wu W, Chen L, Si J, Sun L. The impact of a history of cancer on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma survival. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6: 888-894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abhyankar N, Hoskins KF, Abern MR, Calip GS. Descriptive characteristics of prostate cancer in patients with a history of primary male breast cancer - a SEER analysis. BMC Cancer. 2017;17: 659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Saad AM, Al-Husseini MJ, Elgebaly A, Aboshady OA, Salahia S, Abdel-Rahman O. Impact of prior malignancy on outcomes of stage IV esophageal carcinoma: SEER based study. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12: 417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H. Long-term survival of patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma after a previous malignancy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50: 179-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Smyth EC, Tarazona N, Peckitt C, Armstrong E, Mansukhani S, Cunningham D, Chau I. Exclusion of Gastrointestinal Cancer Patients With Prior Cancer From Clinical Trials: Is This Justified? Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15: e53-e59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dinh KT, Mahal BA, Ziehr DR, Muralidhar V, Chen YW, Viswanathan VB, Nezolosky MD, Beard CJ, Choueiri TK, Martin NE, Orio PF, Sweeney CJ, Trinh QD, Nguyen PL. Risk of prostate cancer mortality in men with a history of prior cancer. BJU Int. 2016;117: E20-E28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pandurengan RK, Dumont AG, Araujo DM, Ludwig JA, Ravi V, Patel S, Garber J, Benjamin RS, Strom SS, Trent JC. Survival of patients with multiple primary malignancies: a study of 783 patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Ann Oncol. 2010;21: 2107-2111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hattori A, Suzuki K, Aokage K, Mimae T, Nagai K, Tsuboi M, Okada M. Prognosis of lung cancer patients with a past history of colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44: 1088-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu J, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Fang W, Yang Y, Hong S, Chen G, Zhao S, Chen X, Zhang Z, Xian W, Shen J, Huang Y, Zhao H, Zhang L. Impact of prior cancer history on the overall survival of younger patients with lung cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | He C, Zhang Y, Cai Z, Lin X. Effect of prior cancer on survival outcomes for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a propensity score analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19: 509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Surveillance E, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov). SEER*Stat Database: Incidence-SEER 18 Regs excluding AK Research Data, Nov 2016 Sub (2000-2014) - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969-2015 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, 2018. |

| 18. | Donin N, Filson C, Drakaki A, Tan HJ, Castillo A, Kwan L, Litwin M, Chamie K. Risk of second primary malignancies among cancer survivors in the United States, 1992 through 2008. Cancer. 2016;122: 3075-3086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, Edwards BK. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist. 2007;12: 20-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 680] [Cited by in RCA: 729] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou H, Huang Y, Qiu Z, Zhao H, Fang W, Yang Y, Zhao Y, Hou X, Ma Y, Hong S, Zhou T, Zhang Y, Zhang L. Impact of prior cancer history on the overall survival of patients newly diagnosed with cancer: A pan-cancer analysis of the SEER database. Int J Cancer. 2018;143: 1569-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer survivorship issues: life after treatment and implications for an aging population. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32: 2662-2668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Corkum M, Hayden JA, Kephart G, Urquhart R, Schlievert C, Porter G. Screening for new primary cancers in cancer survivors compared to non-cancer controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7: 455-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69: 363-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2417] [Cited by in RCA: 3072] [Article Influence: 512.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pruitt SL, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Gerber DE. Revisiting a longstanding clinical trial exclusion criterion: impact of prior cancer in early-stage lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2017;116: 717-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jin S, Pazdur R, Sridhara R. Re-Evaluating Eligibility Criteria for Oncology Clinical Trials: Analysis of Investigational New Drug Applications in 2015. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35: 3745-3752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Pruitt SL. Impact of prior cancer on eligibility for lung cancer clinical trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Björkman N, Qvortrup C, Holsen MH, Wentzel-Larsen T, Glimelius B. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;115: 4679-4687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Duffy SW, Nagtegaal ID, Wallis M, Cafferty FH, Houssami N, Warwick J, Allgood PC, Kearins O, Tappenden N, O'Sullivan E, Lawrence G. Correcting for lead time and length bias in estimating the effect of screen detection on cancer survival. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168: 98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sankila R, Hakulinen T. Survival of patients with colorectal carcinoma: effect of prior breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90: 63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shen M, Boffetta P, Olsen JH, Andersen A, Hemminki K, Pukkala E, Tracey E, Brewster DH, McBride ML, Pompe-Kirn V, Kliewer EV, Tonita JM, Chia KS, Martos C, Jonasson JG, Colin D, Scélo G, Brennan P. A pooled analysis of second primary pancreatic cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163: 502-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Al-Husseini MJ, Saad AM, Mohamed HH, Alkhayat MA, Sonbol MB, Abdel-Rahman O. Impact of prior malignancies on outcome of colorectal cancer; revisiting clinical trial eligibility criteria. BMC Cancer. 2019;19: 863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Youn P, Li H, Milano MT, Stovall M, Constine LS, Travis LB. Long-term survival among Hodgkin's lymphoma patients with gastrointestinal cancer: a population-based study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24: 202-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Laccetti AL, Pruitt SL, Xuan L, Halm EA, Gerber DE. Effect of prior cancer on outcomes in advanced lung cancer: implications for clinical trial eligibility and accrual. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |