Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11712

Peer-review started: June 20, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 13, 2022

Accepted: October 18, 2022

Article in press: October 18, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 140 Days and 23.2 Hours

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy, while MM outcomes have significantly improved due to novel agents and combinations, MM remains an incurable disease. The key goal of treatment in MM is to achieve a maximal response and the subsequent consolidation of response after initial therapy. Many studies analyzed an improved progression-free survival (PFS) following lenalidomide alone maintenance versus placebo or observation after autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) in patients with NDMM. In the SWOG S0777 clinical trial, patients newly diagnosed with MM (NDMM) without ASCT received lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (DXM) maintenance until progressive disease, where PFS and overall survival (OS) were significantly improved. In the present study, we assessed the efficacy and toxicity of the different doses of DXM combined with lenalidomide for maintenance treatment of NDMM for transplant noneligible patients in the standard-risk group.

To investigate the efficacy and adverse effects of different administration modes of DXM combined with lenalidomide for maintenance treatment of MM in standard-risk patients ineligible for transplantation.

A total of 96 MM patients were enrolled in this study, among whom 48 patients received maintenance treatment that consisted of oral administration of 25 milligrams (mg) of lenalidomide from days 1-21 and 40 mg of DXM on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 (DXM 40 mg group), repeated every 4 wk. Another group was treated with oral administration of 25 mg of lenalidomide from days 1-21 and 20 mg of DXM on days 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, and 22-23 (DXM 20 mg group), which was also repeated every 4 wk.

The median PFS was 37.25 mo in the DXM 40.00 mg group and 38.17 mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). The median OS was 50.78 mo in the DXM 40 mg group and 51.69 mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). Fourteen patients in the DXM 40 mg group and 6 patients in the DXM 20 mg group suffered from adverse gastrointestinal reactions after the oral administration of the DXM tablet (P = 0.044). Ten patients suffered from abnormal glucose tolerance (GTA), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), or diabetes mellitus in the DXM 40 mg group during our observation time compared to 19 patients with GTA, IFG, or DM in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.033). Abnormal β-crosslaps or higher were found in 5 patients in the DXM 40 mg group and 12 patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.049). Insomnia or an increase in insomnia compared to the previous condition was evident in 2 patients in the DXM 40 mg group after maintenance treatment for more than 6 mo compared to 11 patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.017).

The DXM 40 mg group exhibited efficacy similar to that of the DXM 20 mg group. However, the DXM 40 mg group had significantly decreased toxicity compared with the DXM 20 mg group in the long term.

Core Tip: Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy. MM treatment includes induction therapy, consolidation therapy, and maintenance therapy. Based on the past clinical activities, we discovered that a part of patients suffered from serious adverse gastrointestinal reactions after oral administration of 40 mg dexamethasone (DXM) once every week. Consequently, we divided DXM 40 mg administered once a day into 20 mg continuously administered over two days, after which we compared the efficacy and toxicity in DXM 40 mg and 20 mg group as maintenance. The two groups have equally efficience as maintenance treatment in standard-risk patients’ non-eligible for transplantation. However, DXM 40 mg once per day per week exhibited a higher incidence rate in adverse gastrointestinal reactions in short-term, but lower non-hematological toxicity in the long-term contained bone lost, abnormal of blood glucose and insomnia. DXM 40 mg once per day every week may be safer and lead to a better quality of life.

- Citation: Hu SL, Liu M, Zhang JY. Comparing the efficacy of different dexamethasone regimens for maintenance treatment of multiple myeloma in standard-risk patients non-eligible for transplantation. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 11712-11725

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/11712.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.11712

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy characterized by anemia, renal failure, skeletal destruction, hypercalcemia, and other systemic symptoms[1-4]. Although the survival outcomes of MM have markedly improved with the use of proteasome inhibitors (PIs) (e.g., bortezomib), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) (e.g., thalidomide, lenalidomide), and other mechanisms of action, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies, relapse remains a serious problem[5-8]. Treatment of MM includes induction therapy, autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for eligible patients, or non-ASCT for noneligible patients, followed by consolidation and maintenance therapy[8,9].

The key goal of treatment in MM is to achieve a maximal response and the subsequent consolidation of response after initial therapy[10,11]. Many clinical trials have reported that consolidation therapy could improve the response after induction therapy[12,13]. Maintenance therapies are used to control disease and lengthen the response by delaying relapse, thus prolonging both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)[11]. The efficacy and safety of maintenance therapy, which has been used for decades, has substantially improved in recent years due to IMiDs and PIs[12,14]. Lenalidomide alone is considered a useful maintenance treatment for MM after autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) and has been shown to prolong PFS and OS vs placebo[15,16]. Transplant noneligible (TNE) patients may be administered maintenance therapy according to their initial treatment. Both IMiDs and PIs have shown efficacy in this group, especially lenalidomide. According to the Mayo Clinic Guideline, it is recommended to use lenalidomide for maintenance treatment for TNE patients in the standard-risk group. In the SWOG S0777 clinical trial, patients newly diagnosed with MM (NDMM) without ASCT received lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone (DXM) maintenance until progressive disease (PD), where PFS and OS were significantly improved. Another meta-analysis also demonstrated that lenalidomide plus glucocorticoids was the most effective option for the maintenance of NDMM[17]. However, the usage and dosage of glucocorticoids used in different centers are not the same. The role of maintenance therapy has gained increasing importance, especially among patients who are ineligible and eligible for transplantation, for whom this is a valuable option in clinical trial settings[10,12,13]. The use of maintenance therapy needs to be guided by the individual patient situation in actual clinical practice. In the present study, we assessed the efficacy and toxicity of different doses of DXM combined with lenalidomide for maintenance treatment of NDMM for TNE patients in the standard-risk group.

A total of 96 patients were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. All patients diagnosed with MM for the first time that was treated at Lishui Municipal Central Hospital between January 2016 and December 2020 was enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients were diagnosed and assigned to a risk group according to the 2020 Mayo Stratification for Myeloma and Risk-adapted Therapy (mSMART) guidelines for newly diagnosed myeloma; (2) patients received 8-12 cycles of chemotherapy according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Version 2021 guidelines: 78 patients received bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (VRD) regimens, 16 patients received bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCD) regimens, and 2 patients received bortezomib and dexamethasone (RD) regimens because of poor clinical conditions; (3) patients received maintenance therapy after response evaluation ≥ complete response (CR); and (4) response criteria were set according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Version 2021 guidelines. The patients were not allowed to participate in other clinical research. PFS, OS, study withdrawal or nondisease-related death were used as the endpoints. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Serious organ dysfunction except for renal impairment; (2) severe osteoporosis; (3) organic mental illness; and (4) additional corticosteroid treatment by any reason during the study period.

The research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Lishui Municipal Central Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient or family member.

The present study was a randomized controlled, single-blind trial that did not intervene with patients' treatments. Seventy-eight patients received a VRD regimen consisting of subcutaneous administration of 1.3 mg/m2 of bortezomib on days 1, 8, 15, and 22; oral administration of 25 mg of lenalidomide from days 1-21; and oral administration of 40 mg of DXM on days 1, 8, 15, and 22, repeated every 4 wk. Sixteen patients underwent a VCD regimen that included subcutaneous administration of 1.3 mg/m2 of bortezomib on days 1, 8, 15, and 22; oral administration of 300 mg/m2 of cyclophosphamide on days 1, 8, 15, and 22; and oral administration of 40 mg of DXM on days 1, 8, 15, and 22; repeated every 4 wk. Two patients received a PD regimen that included subcutaneous administration of 1.3 mg/m2 of bortezomib on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 and 20 mg of DXM on the day of and the day after bortezomib administration, which was repeated every 4 wk. All patients received 6-8 cycles of therapy. The patients who achieved CR after chemotherapy continued to receive maintenance therapy and were randomly assigned into two test groups. One group received oral administration of 25 mg of lenalidomide from days 1-21 and oral administration of 40 mg of DXM on days 1, 8, 15, and 22, repeated every 4 wk (40 mg group). The other group received oral administration of 25 mg of lenalidomide from days 1-21 and oral administration of 20 mg of DXM on days 1-2, 8-9, 15-16, and 22-23, repeated every 4 wk (20 mg group). Every patient received maintenance therapy until PD.

The baseline data were collected as follows: Age, sex, monoclonal protein (M protein), ISS stage, Durie-Salmon (DS) stage, classification, glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT), glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), catabolite activator protein (CRP), albumin/globulin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), t(6;14), t(11;14), urea nitrogen (UA), creatinine (Cr), hemoglobin (HGB), and platelet (PLT) count at first diagnosis, glucose tolerance abnormal (GTA), impaired fasting glucose (IFG), diabetes mellitus (DM), β-crosslaps (β-CTX), blood pressure (BP), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), peptic ulcer (PU), acne, osteoporosis, and insomnia after the start of maintenance therapy.

According to the 2020 mSMART guidelines, the following factors were considered high risk: High-risk genetic abnormalities containing t(4; 14), t(14; 16), t(14; 20), del 17p, p53 mutation, or gain 1q; RISS stage 3; high plasma cell S-phase; and a high-risk GEP signature. Standard risk was assessed based on trisomies t(11; 14) and t(6; 14). The detailed response criteria were as follows: (1) CR: Plasma cells in bone marrow aspirate < 5%, negative immunofixation in serum and urine, and disappearance of any soft tissue plasmacytomas; and (2) PD: Increase of 25% from the lowest confirmed response value in one or more of the following criteria: Serum M protein increase by ≥ 1 g/dL, if the lowest M component was ≥ 5 g/dL; and serum M protein with an absolute increase of ≥ 0.5 g/dL or urine M protein with an absolute increase of ≥ 200 mg/24 h. GTA was defined as a blood glucose level of 7.8-11.0 micromoles /Liter (mmol/L) 2 h after a meal. IFG was considered a fasting blood glucose level of 5.6-6.9 mmol/L. Abnormal BP was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg. Abnormal β-CTX was defined as > 783 pg/mL.

The median observation time was 42 mo.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 24.0 software. PFS and OS were analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models. A stepwise selection method was used to determine the potential confounding covariates. The association of risk factors with PFS and OS was used to examine hazard ratios (HRs). Standard survival curves for OS and PFS were created using the Kaplan-Meier method. The baseline characteristics and GTA, IFG, DM, β-CTX, osteoporosis, hypertension, TG, TC, acne, PU, and insomnia were compared between groups using a t test. A P value < 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

Among the 94 patients who were enrolled in the study, 48 were assigned to the DXM 40 mg group and 48 were assigned to the DXM 20 mg group. The DXM 40 mg group consisted of 26 males and 22 females with a median age of 69.0 years ± 7.2 years, while the DXM 20 mg group included 30 males and 18 females with a median age of 70.0 years ± 8.4 years. In the DXM 40 mg group, one (2%) patient was DS stage I, 6 (12.5%) patients were DS stage II, and 41 (85.5%) patients were DS stage III, compared to 1 (2%), 10 (20.8%), and 37 (77.2%) patients at DS stage I, II, III in the DXM 20 mg group, respectively. Twenty-two (45.8%) patients had ISS stage II disease and 18 (38.5%) patients had ISS stage III disease in the DXM 40 mg group, compared to 19 (39.6%) patients with ISS stage II disease and 19 (39.6%) patients with ISS stage III disease in the DXM 20 mg group. There were no cases with t(6;14) positivity among newly diagnosed patients in the DXM 40 mg group, compared to 2 (4.2%) such patients in the DXM 20 mg group. In the DXM 40 mg group, 7 (14.6%) patients were t(11;14) positive compared to 8 (16.7%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group. Thirteen (27.1%) patients were found to have lower PLT counts (≤ 100 × 109/L) in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 11 (22.9%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group. There were just 4 (8.3%) cases of abnormal GPT and 7 (14.6%) cases of abnormal GOT in the DXM 40 mg group, compared to 2 (4.2%) cases of abnormal GPT and 6 (12.5%) cases of abnormal GOT in the DXM 20 mg group. HGB was estimated to be 68.0 ± 13.4 in the DXM 40 mg group, while it was estimated to be 67.0 ± 14.7 in the DXM 20 mg group. A total of 20 (41.7%) patients had abnormal Cr in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 16 (33.3%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group. The treatment was compared between the two groups. In the DXM 40 mg group, 38 (79.2%) patients received the VRD regimen, and 10 (20.8%) patients received the PCD regimen. Forty (83.3%) patients received the VRD regimen, 6 (12.5%) patients received the PCD regimen, and 2 (4.2%) patients received the PD regimen in the DXM 20 mg group (Table 1).

| Parameters | DXM 40 mg treatment (n = 48) | DXM 20 mg treatment (n = 48) | P value |

| Age, yr | 69.0 ± 7.2 | 70.0 ± 8.4 | 0.646 |

| Gender (male/female) | 26/22 | 30/18 | 0.408 |

| DS stage | 0.544 | ||

| I | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | |

| II | 6 (12.5%) | 10 (20.8) | |

| III | 41 (85.5%) | 37 (77.2%) | |

| ISS stage | 0.791 | ||

| I | 8 (16.7%) | 10 (20.8) | |

| II | 22 (45.8%) | 19 (39.6%) | |

| III | 18 (38.5) | 19 (39.6%) | |

| CRP | 13 (27.1%) | 16 (33.3%) | 0.461 |

| HGB | 68.0 ± 13.4 | 67.0 ± 14.7 | 0.525 |

| Platelet | 13 (27.1%) | 11 (22.9%) | 0.637 |

| t(6;14) | 0 | 2 (4.2%) | 0.093 |

| t(11;14) | 7 (14.6%) | 8 (16.7%) | 0.779 |

| ALT | 4 (8.3%) | 2 (4.2%) | 0.399 |

| AST | 7 (14.6%) | 6 (12.5%) | 0.765 |

| LDH | 9 (18.6%) | 10 (20.8) | 0.798 |

| Cr | 20 (41.7%) | 16 (33.3%) | 0.399 |

| UA | 17 (35.4) | 12 (25%) | 0.266 |

| Treatment | 0.147 | ||

| VRD | 38 (79.2%) | 40 (83.3%) | |

| PCD | 10 (20.8) | 6 (12.5%) | |

| PD | 0 | 2 (4.2%) | |

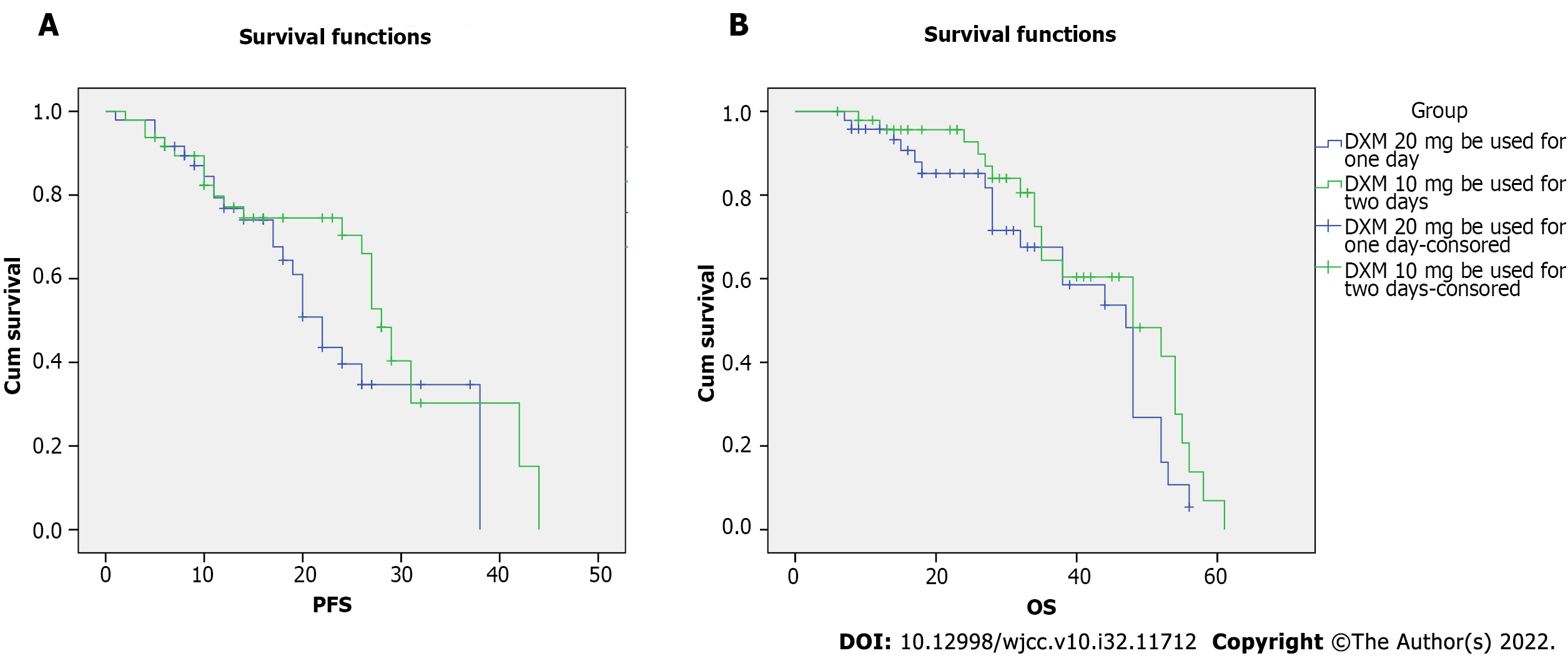

All patients received 8-10 cycles of chemotherapy and arrived at complete remission before the start of maintenance treatment. The median PFS for all patients was 37.25 (95%CI: 24.98-39.52) mo in the DXM 40 mg group and 38.17 (95%CI: 35.18-41.15) mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). The data indicated no significant difference in PFS between the two groups. The K-M curve and log-rank tests were used to analyze PFS (Figure 1A). Age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P < 0.01), ALT (P = 0.004), AST (P = 0.001), LDH (P = 0.021), and treatment (P = 0.009) were associated with PFS in the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2). According to the multivariate Cox regression, age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P = 0.007), and DM (P = 0.007) were associated with PFS (Table 3). The median overall survival (OS) was 50.78 (95%CI: 46.66-54.91) mo in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 51.69 (95%CI: 47.31-56.07) mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). The K-M curve and log-rank tests were used to analyze OS (Figure 1B). No difference was noted between the two groups in OS. Finally, age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P < 0.01), t(11;14) (P = 0.003), and IFG (P = 0.03) were influencing factors in the univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 4). In the multivariate Cox regression, age (P < 0.01) and ISS stage (P = 0.007) were associated with OS (Table 5).

| Parameters | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| DXM 40 mg vs 20 mg | 0.171 | 0.649 | 0.350 | 1.205 |

| Age, yr | 0 | 1.214 | 1.150 | 1.283 |

| Gender | 0.821 | 0.930 | 0.497 | 1.740 |

| Classification | 0.303 | 0.336 | 0.042 | 2.678 |

| DS stage | 0.185 | 1.701 | 0.776 | 3.726 |

| ISS stage | 0 | 2.850 | 1.734 | 4.682 |

| Platelet | 0.363 | 1.011 | 0.998 | 1.034 |

| t(6;14) | 0.586 | 0.048 | 0 | 2739.308 |

| t(11;14) | 0.185 | 0.598 | 0.280 | 1.278 |

| CRP | 0.175 | 1.010 | 0.995 | 1.025 |

| HGB | 0.285 | 0.992 | 0.979 | 1.006 |

| ALT | 0.004 | 1.014 | 1.005 | 1.024 |

| AST | 0.001 | 1.014 | 1.006 | 1.023 |

| ALB | 0.573 | 1.010 | 0.976 | 1.044 |

| GLO | 0.702 | 0.998 | 0.985 | 1.010 |

| A/G | 0.458 | 0.872 | 0.608 | 1.251 |

| LDH | 0.021 | 1.002 | 1.000 | 1.003 |

| Ca | 0.652 | 0.982 | 0.909 | 1.062 |

| P | 0.907 | 0.980 | 0.701 | 1.37 |

| M-protein | 0.982 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.004 |

| Cr | 0.325 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.001 |

| UA | 0.169 | 1.001 | 1.000 | 1.002 |

| Treatment | 0.009 | 1.913 | 1.173 | 3.119 |

| GTA | 0.565 | 0.707 | 0.217 | 2.300 |

| IFG | 0.134 | 0.44 | 0.151 | 1.288 |

| DM | 0.034 | 2.343 | 1.068 | 5.141 |

| Β-CTX | 0.874 | 1.065 | 0.487 | 2.328 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.533 | 1.301 | 0.568 | 2.980 |

| Hypertension | 0.668 | 1.254 | 0.445 | 3.536 |

| TG | 0.716 | 1.156 | 0.529 | 2.525 |

| TC | 0.812 | 1.095 | 0.518 | 2.315 |

| Acne | 0.965 | 0.977 | 0.348 | 2.746 |

| PU | 0.983 | 0.988 | 0.349 | 2.799 |

| Insomnia | 0.949 | 1.029 | 0.427 | 2.479 |

| Parameters | P value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Age, yr | 0 | 1.218 | 1.140 | 1.302 |

| ISS stage | 0.007 | 2.256 | 1.249 | 4.076 |

| ALT | 0.057 | 1.015 | 1.000 | 1.030 |

| AST | 0.240 | 1.009 | 0.994 | 1.023 |

| LDH | 0.199 | 1.001 | 0.999 | 1.004 |

| Treatment | 0.192 | 1.482 | 0.821 | 2.672 |

| DM | 0.005 | 3.458 | 1.456 | 8.213 |

| Parameters | P value | HR | 95% CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| DXM 40 mg vs 20 mg | 0.171 | 0.652 | 0.353 | 1.202 |

| Age, yr | 0.000 | 1.178 | 1.121 | 1.238 |

| Gender | 0.602 | 0.846 | 0.451 | 1.587 |

| Classification | 0.14 | 0.211 | 0.027 | 1.665 |

| DS stage | 0.067 | 2.271 | 0.944 | 5.462 |

| ISS stage | 0.000 | 5.245 | 3.041 | 9.048 |

| Platelet | 0.417 | 1.010 | 0.987 | 1.033 |

| t(6;14) | 0.489 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 278.970 |

| t(11;14) | 0.003 | 0.288 | 0.128 | 0.649 |

| CRP | 0.086 | 1.013 | 0.998 | 1.027 |

| HGB | 0.050 | 0.983 | 0.967 | 1.000 |

| ALT | 0.194 | 1.007 | 0.997 | 1.017 |

| AST | 0.070 | 1.008 | 0.999 | 1.016 |

| ALB | 0.940 | 1.001 | 0.971 | 1.032 |

| GLO | 0.945 | 1.000 | 0.986 | 1.013 |

| A/G | 0.911 | 0.957 | 0.668 | 1.371 |

| LDH | 0.209 | 1.001 | 0.999 | 1.003 |

| Ca | 0.906 | 0.968 | 0.564 | 1.662 |

| P | 0.627 | 0.919 | 0.652 | 1.293 |

| M-protein | 0.652 | 0.998 | 0.992 | 1.005 |

| Cr | 0.623 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.001 |

| UA | 0.375 | 1.001 | 0.999 | 1.002 |

| Treatment | 0.173 | 1.375 | 0.869 | 2.174 |

| GTA | 0.546 | 0.694 | 0.212 | 2.271 |

| IFG | 0.030 | 0.263 | 0.078 | 0.881 |

| DM | 0.203 | 1.661 | 0.760 | 3.631 |

| β-CTX | 0.840 | 1.088 | 0.479 | 2.474 |

| Osteoporosis | 0.703 | 1.187 | 0.492 | 2.862 |

| Hypertension | 0.730 | 1.201 | 0.424 | 3.404 |

| TG | 0.642 | 0.823 | 0.363 | 1.869 |

| TC | 0.715 | 0.866 | 0.398 | 1.881 |

| Acne | 0.995 | 1.003 | 0.354 | 2.842 |

| PU | 0.686 | 0.808 | 0.286 | 2.277 |

| Insomnia | 0.725 | 1.159 | 0.509 | 2.637 |

| Parameters | P value | HR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Age, yr | 0 | 1.107 | 1.048 | 1.170 |

| ISS stage | 0 | 3.707 | 1.798 | 7.643 |

| t(11;14) | 0.055 | 0.399 | 0.156 | 1.019 |

| IFG | 0.246 | 0.482 | 0.140 | 1.655 |

The two groups were compared with reference to nonhematological toxicity. Fourteen (29.2%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group experienced adverse gastrointestinal reactions after the oral administration of the DXM tablet compared to 6 (12.5%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.044) who experienced similar symptoms. Three (6.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group had GTA vs 5 (10.4%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.426). IFG was observed in 4 (8.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group vs 7 (14.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.303). Three (6.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group were diagnosed with DM compared to 7 (14.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.162). A total of 10 (20.8%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group had abnormal blood glucose vs 19 (39.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.033). The results of abnormal blood glucose after maintenance treatment were significantly different between the two groups. β-CTX levels higher than the reference value within 2 years after receiving maintenance treatment were found in 5 (10.4%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 12 (25%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.049). Five (10.4%) patients were diagnosed with osteoporosis through bone density testing more than two years after receiving maintenance treatment in the DXM 40 mg group vs 7 (14.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.487). Hypertension occurred in 4 (8.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group and 5 (10.4%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.677). Both the DXM 40 mg group and the DXM 20 mg group had high TGs in 7 (14.6%) patients (P = 0.933). Eight (16.7%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group had high TC compared to 9 (18.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.717). Three (6.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group were diagnosed with acne at the dermatological exam compared to 6 (12.5%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.267). Endoscopic examination revealed peptic ulcer lesions in 3 (6.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 4 (8.3%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.654). Three (6.3%) patients suffered from insomnia or had worsened episodes of insomnia compared to before clinical service after maintenance treatment for more than 6 mo in the DXM 40 mg group, compared to 11 (22.9%) patients with such symptoms in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.017) (Table 6).

| Toxicity | DXM 40 mg group | DXM 20 mg group | P value |

| Adverse gastrointestinal reactions | 14 | 6 | 0.044 |

| GTA | 3 | 5 | 0.426 |

| IFG | 4 | 7 | 0.303 |

| DM | 3 | 7 | 0.162 |

| GTA + TFG + DM | 10 | 19 | 0.033 |

| β-CTX | 5 | 12 | 0.049 |

| Osteoporosis | 5 | 7 | 0.487 |

| Hypertension | 4 | 5 | 0.677 |

| TG | 7 | 7 | 0.933 |

| TC | 8 | 9 | 0.717 |

| Acne | 3 | 6 | 0.267 |

| PU | 3 | 4 | 0.654 |

| Insomnia | 3 | 11 | 0.017 |

While MM outcomes have significantly improved due to novel agents and combinations, MM remains an incurable disease[18]. This condition is characterized by periods of active progression that require systemic therapy dependent on biology as well as new diagnoses and ongoing treatment. MM treatment includes induction therapy, consolidation therapy, and maintenance therapy[19,20]. The aim of maintenance therapy is to extend the period of disease quiescence through continued treatment, thus improving PFS and OS[21]. Various maintenance treatments in NDMM have been discussed within the current guidelines and recommendations[22-27].

Many studies have reported improved PFS following lenalidomide alone maintenance vs placebo or observation after ASCT in patients with NDMM[28-30]. The Myeloma XI trial has also reported significant improvement in PFS and PFS2 by comparing the efficacy of lenalidomide maintenance vs observation in the nontransplant pathway[31,32]. Notably, the PFS benefit of lenalidomide maintenance was present regardless of the cytogenetic risk. These data demonstrated that outcomes were more deficient in high-risk patients[31]. Consequently, according to the 2020 mSMART guidelines, transplant-ineligible patients with low cytogenetic risk were advised lenalidomide for maintenance. Two trials showed a moderate PFS benefit by adding glucocorticoids to lenalidomide vs lenalidomide alone in TNE patients[33-35]. In the SWOG S0777 trial, all patients without transplant received Rd maintenance until PD, and a median PFS of 43 mo was achieved in those who initially received a VRD regimen[36]. In this clinical trial, Rd was used with lenalidomide plus 40 mg oral DXM once a day on days 1, 8, 15, and 22[36]. In the FIRST trial, patients without ASCT used Rd maintenance until PD showed that the PFS benefit at the prespecified PFS analysis was reaffirmed vs Rd for 18 cycles[37]. The EMN01 trial demonstrated that PFS from the start of maintenance was 22.2 mo with RP vs 18.6 mo with lenalidomide alone. Additionally, grade 3/4 neutropenia was reported less frequently in the RP group vs the lenalidomide alone group[35].

Effective and feasible maintenance therapy should have a convenient administration route for a prolonged period, emphasizing the tolerability and toxicity of maintenance therapy[13,38,39]. Several studies have specifically addressed the quality of life (QOL) in TNE patients undergoing maintenance therapy, reporting that it can improve QOL in the TNE population[40-42]. Considering the concern about the effects of hematological toxicity caused by lenalidomide, a number of clinical trials have reported that it is generally well tolerated, with the main side effects of hematologic toxicity, infection, and rare thrombotic events[41,43].

Based on past clinical activities, we discovered that some patients suffered serious adverse gastrointestinal reactions after the oral administration of 40 mg of DXM once every week. Consequently, we divided 40 mg of DXM administered once a day into 20 mg administered continuously over two days, after which we compared the efficacy and toxicity in the DXM 40 mg and 20 mg groups as maintenance treatment of MM for TNE patients in the standard-risk group. MM patients were evaluated according to the following parameters: (1) Efficacy: All patients received 8-10 cycles of chemotherapy and arrived at complete remission before the start of maintenance treatment. The median PFS for all patients was 37.25 (95%CI: 24.98-39.52) mo in the DXM 40 mg group and 38.17 (95%CI: 35.18-41.15) mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). The data revealed no significant difference in PFS between the two groups. The median overall survival (OS) time was 50.78 (95%CI: 46.66-54.91) mo in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 51.69 (95%CI: 47.31-56.07) mo in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.171). No difference was noted between the two groups in OS. Our results showed similar clinical efficacy in the DXM 40 mg and 20 mg groups as maintenance treatment of MM for TNE patients in the standard-risk group; and (2) Toxicity: We analyzed the nonhematological toxicity as determined by the following adverse gastrointestinal reactions: GTA, IFG, DM, β-CTX, osteoporosis, hypertension, TG, TC, acne, PU, and insomnia. Fourteen (29.2%) patients suffered from adverse gastrointestinal reactions after the oral administration of DXM tablets in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 6 (12.5%) patients with similar symptoms in the DXM 20 mg group. Accordingly, the DXM 40 mg group exhibited a higher incidence rate than the DXM 20 mg group with reference to adverse gastrointestinal reactions (P = 0.044). Three (6.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group had GTA compared to 5 (10.4%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.426). IFG was observed in 4 (8.3%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group and 7 (14.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.303). Three (6.3%) patients were diagnosed with DM in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 7 (14.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.162). These results showed no differences in the effect on blood glucose between the two groups. However, when GTA, IFG and DM were combined, they showed notable differences.

A total of 10 (20.8%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group had abnormal blood glucose compared to 19 (39.6%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.033). The results of abnormal blood glucose after maintenance treatment showed a significant difference between the two groups. A more frequent effect on blood glucose was observed in the DXM 20 mg group. β-CTX levels above the reference value within 2 years after receiving maintenance treatment were found in 5 (10.4%) patients in the DXM 40 mg group compared to 12 (25%) patients in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.049). The DXM 40 mg group had less bone than the DXM 20 mg group in the long term. There were no differences between the two groups related to hypertension, hyperlipidemia, acne, or peptic ulcer lesions in our observation. Three (6.3%) patients reported insomnia at their clinical follow-up after maintenance treatment lasting more than 6 mo in the DXM 40 mg group, while 11 (22.9%) patients experienced such symptoms in the DXM 20 mg group (P = 0.017). This suggested that the treatment approach used in the DXM 20 mg group had a stronger effect on sleep quality. The factors that influenced PFS were age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P < 0.01), ALT (P = 0.004), AST (P = 0.001), LDH (P = 0.021), and treatment (P = 0.009), as determined by univariate Cox regression analysis. The results of the multivariate Cox regression revealed that age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P = 0.007), and DM (P = 0.007) were associated with PFS. Previous studies have reported age and ISS stage as independent prognostic risk factors for PFS[44]. The diagnosis of DM within maintenance treatment time did not result as a disadvantageous factor for PFS; however, more cases are needed to support these results. According to the univariate Cox regression analysis, age (P < 0.01), ISS stage (P < 0.01), t(11;14) (P = 0.003), and IFG (P = 0.03) were not associated with OS. In the multivariate Cox regression, age (P < 0.01) and ISS stage (P = 0.007) were associated with OS, which was consistent with previous studies[44].

The present study has several limitations. First, only 17 patients were included with cytogenetic abnormalities. Second, our research was a single-center retrospective study. Third, the induction treatment was performed using VRD, PCD, and PD regimens. Different initial treatments and different cycles may influence the reliability of the results. Last, the sample size was relatively small. We do not know if different classifications could affect the clinical efficacy of the two treatments.

In conclusion, 40 mg of DXM administered once per day every week was equally efficient as 20 mg of DXM administered continuously for two days every week as maintenance treatment of MM for TNE patients in the standard-risk group. However, 40 mg of DXM administered once per day every week exhibited a higher incidence of adverse gastrointestinal reactions in the short term but lower nonhematological toxicity in the long term, including bone loss, abnormal blood glucose and insomnia. Lenalidomide plus DXM can be used for maintenance treatment for MM in the standard-risk group of TNE patients. The administration of 40 mg of DXM once per day every week may be safer and lead to a better quality of life than 20 mg of DXM administered continuously for two days every week.

Forty mg of DXM administered once per day every week was equally efficient as 20 mg of DXM administered continuously for two days every week as maintenance treatment of multiple myeloma for TNE patients in the standard-risk group. However, 40 mg of DXM administered once per day every week exhibited a higher incidence of adverse gastrointestinal reactions in the short term but lower nonhematological toxicity in the long term, including bone loss, abnormal blood glucose and insomnia. Lenalidomide plus DXM can be used for maintenance treatment for MM in the standard-risk group of TNE patients. The administration of 40 mg of DXM once per day every week may be safer and lead to a better quality of life than 20 mg of DXM administered continuously for two days every week.

Myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy. MM treatment includes induction therapy, consolidation therapy, and maintenance therapy.

Consequently, we divided DXM 40mg administered once a day into 20 mg continuously administered over two days, after which we compared the efficacy and toxicity in DXM 40 mg and 20 mg group as maintenance.

Dexamethasone (DXM) combined with lenolidomide for maintenance treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) in standard-risk patients non-eligible for transplantation.

DXM combined with lenolidomide for maintenance treatment into two groups. And comparsion with efficacy and toxicity.

Eefficience as maintenance treatment in standard-risk patients non-eligible for transplantation. However, DXM 40 mg once per day per week exhibited a higher incidence rate in adverse gastroin

Forty mg once per day every week may be safer and lead to a better quality of life.

The data were analyzed by SPSS 24.0 software. Progression-free survival and overall survival were analyzed using Cox proportional hazard models.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arunachalam J, India; Glumac S, Croatia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1860-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1078] [Cited by in RCA: 1070] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749-757. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Palumbo A, Cerrato C. Diagnosis and therapy of multiple myeloma. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28:263-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yi JE, Lee SE, Jung HO, Min CK, Youn HJ. Association between left ventricular function and paraprotein type in patients with multiple myeloma. Korean J Intern Med. 2017;32:459-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mey UJ, Leitner C, Driessen C, Cathomas R, Klingbiel D, Hitz F. Improved survival of older patients with multiple myeloma in the era of novel agents. Hematol Oncol. 2016;34:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Hayman SR, Buadi FK, Zeldenrust SR, Dingli D, Russell SJ, Lust JA, Greipp PR, Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516-2520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1674] [Cited by in RCA: 1808] [Article Influence: 100.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bianchi G, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Promising therapies in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2015;126:300-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:719-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Multiple Myeloma. 2018. [cited 3 August 2022]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf. 2018. |

| 10. | Lonial S, Anderson KC. Association of response endpoints with survival outcomes in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2014;28:258-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ludwig H, Durie BG, McCarthy P, Palumbo A, San Miguel J, Barlogie B, Morgan G, Sonneveld P, Spencer A, Andersen KC, Facon T, Stewart KA, Einsele H, Mateos MV, Wijermans P, Waage A, Beksac M, Richardson PG, Hulin C, Niesvizky R, Lokhorst H, Landgren O, Bergsagel PL, Orlowski R, Hinke A, Cavo M, Attal M; International Myeloma Working Group. IMWG consensus on maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:3003-3015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Röllig C, Knop S, Bornhäuser M. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2015;385:2197-2208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 485] [Article Influence: 48.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Musto P, Montefusco V. Are maintenance and continuous therapies indicated for every patient with multiple myeloma? Expert Rev Hematol. 2016;9:743-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lipe B, Vukas R, Mikhael J. The role of maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6:e485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McCarthy PL, Holstein SA, Petrucci MT, Richardson PG, Hulin C, Tosi P, Bringhen S, Musto P, Anderson KC, Caillot D, Gay F, Moreau P, Marit G, Jung SH, Yu Z, Winograd B, Knight RD, Palumbo A, Attal M. Lenalidomide Maintenance After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3279-3289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Syed YY. Lenalidomide: A Review in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma as Maintenance Therapy After ASCT. Drugs. 2017;77:1473-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gay F, Jackson G, Rosiñol L, Holstein SA, Moreau P, Spada S, Davies F, Lahuerta JJ, Leleu X, Bringhen S, Evangelista A, Hulin C, Panzani U, Cairns DA, Di Raimondo F, Macro M, Liberati AM, Pawlyn C, Offidani M, Spencer A, Hájek R, Terpos E, Morgan GJ, Bladé J, Sonneveld P, San-Miguel J, McCarthy PL, Ludwig H, Boccadoro M, Mateos MV, Attal M. Maintenance Treatment and Survival in Patients With Myeloma: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1389-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Gertz MA, Buadi FK, Pandey S, Kapoor P, Dingli D, Hayman SR, Leung N, Lust J, McCurdy A, Russell SJ, Zeldenrust SR, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia. 2014;28:1122-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1035] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 97.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lahuerta JJ, Paiva B, Vidriales MB, Cordón L, Cedena MT, Puig N, Martinez-Lopez J, Rosiñol L, Gutierrez NC, Martín-Ramos ML, Oriol A, Teruel AI, Echeveste MA, de Paz R, de Arriba F, Hernandez MT, Palomera L, Martinez R, Martin A, Alegre A, De la Rubia J, Orfao A, Mateos MV, Blade J, San-Miguel JF; GEM (Grupo Español de Mieloma)/PETHEMA (Programa para el Estudio de la Terapéutica en Hemopatías Malignas) Cooperative Study Group. Depth of Response in Multiple Myeloma: A Pooled Analysis of Three PETHEMA/GEM Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2900-2910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lehners N, Becker N, Benner A, Pritsch M, Löpprich M, Mai EK, Hillengass J, Goldschmidt H, Raab MS. Analysis of long-term survival in multiple myeloma after first-line autologous stem cell transplantation: impact of clinical risk factors and sustained response. Cancer Med. 2018;7:307-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Anderson KC, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, Stewart AK, Weber D, Richardson P; ASH/FDA Panel on Clinical Endpoints in Multiple Myeloma. Clinically relevant end points and new drug approvals for myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gay F, Engelhardt M, Terpos E, Wäsch R, Giaccone L, Auner HW, Caers J, Gramatzki M, van de Donk N, Oliva S, Zamagni E, Garderet L, Straka C, Hajek R, Ludwig H, Einsele H, Dimopoulos M, Boccadoro M, Kröger N, Cavo M, Goldschmidt H, Bruno B, Sonneveld P. From transplant to novel cellular therapies in multiple myeloma: European Myeloma Network guidelines and future perspectives. Haematologica. 2018;103:197-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kumar SK, Callander NS, Alsina M, Atanackovic D, Biermann JS, Castillo J, Chandler JC, Costello C, Faiman M, Fung HC, Godby K, Hofmeister C, Holmberg L, Holstein S, Huff CA, Kang Y, Kassim A, Liedtke M, Malek E, Martin T, Neppalli VT, Omel J, Raje N, Singhal S, Somlo G, Stockerl-Goldstein K, Weber D, Yahalom J, Kumar R, Shead DA. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Multiple Myeloma, Version 3.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gonsalves WI, Buadi FK, Ailawadhi S, Bergsagel PL, Chanan Khan AA, Dingli D, Dispenzieri A, Fonseca R, Hayman SR, Kapoor P, Kourelis TV, Lacy MQ, Larsen JT, Muchtar E, Reeder CB, Sher T, Stewart AK, Warsame R, Go RS, Kyle RA, Leung N, Lin Y, Lust JA, Russell SJ, Zeldenrust SR, Fonder AL, Hwa YL, Hobbs MA, Mayo AA, Hogan WJ, Rajkumar SV, Kumar SK, Gertz MA, Roy V. Utilization of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for the treatment of multiple myeloma: a Mayo Stratification of Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) consensus statement. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:353-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, San Miguel JF, Larocca A, Niesvizky R, Morgan G, Landgren O, Hajek R, Einsele H, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos MA, Richardson PG, Cavo M, Spencer A, Stewart AK, Shimizu K, Lonial S, Sonneveld P, Durie BG, Moreau P, Orlowski RZ. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement for the management, treatment, and supportive care of patients with myeloma not eligible for standard autologous stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:587-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sonneveld P, Avet-Loiseau H, Lonial S, Usmani S, Siegel D, Anderson KC, Chng WJ, Moreau P, Attal M, Kyle RA, Caers J, Hillengass J, San Miguel J, van de Donk NW, Einsele H, Bladé J, Durie BG, Goldschmidt H, Mateos MV, Palumbo A, Orlowski R. Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: a consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood. 2016;127:2955-2962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 77.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Moreau P, San Miguel J, Sonneveld P, Mateos MV, Zamagni E, Avet-Loiseau H, Hajek R, Dimopoulos MA, Ludwig H, Einsele H, Zweegman S, Facon T, Cavo M, Terpos E, Goldschmidt H, Attal M, Buske C; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:iv52-iv61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 479] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, Hurd DD, Hassoun H, Richardson PG, Giralt S, Stadtmauer EA, Weisdorf DJ, Vij R, Moreb JS, Callander NS, Van Besien K, Gentile T, Isola L, Maziarz RT, Gabriel DA, Bashey A, Landau H, Martin T, Qazilbash MH, Levitan D, McClune B, Schlossman R, Hars V, Postiglione J, Jiang C, Bennett E, Barry S, Bressler L, Kelly M, Seiler M, Rosenbaum C, Hari P, Pasquini MC, Horowitz MM, Shea TC, Devine SM, Anderson KC, Linker C. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 929] [Cited by in RCA: 889] [Article Influence: 68.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Marit G, Caillot D, Moreau P, Facon T, Stoppa AM, Hulin C, Benboubker L, Garderet L, Decaux O, Leyvraz S, Vekemans MC, Voillat L, Michallet M, Pegourie B, Dumontet C, Roussel M, Leleu X, Mathiot C, Payen C, Avet-Loiseau H, Harousseau JL; IFM Investigators. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1782-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 871] [Cited by in RCA: 890] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, Di Raimondo F, Ben Yehuda D, Petrucci MT, Pezzatti S, Caravita T, Cerrato C, Ribakovsky E, Genuardi M, Cafro A, Marcatti M, Catalano L, Offidani M, Carella AM, Zamagni E, Patriarca F, Musto P, Evangelista A, Ciccone G, Omedé P, Crippa C, Corradini P, Nagler A, Boccadoro M, Cavo M. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:895-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 605] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jackson G. Lenalidomide maintenance significantly improves outcomes compared to observation irrespective of cytogenetic risk: results of the Myeloma XI Trial. Blood. 2017;130:436. |

| 32. | Jackson GH, Davies FE, Pawlyn C, Cairns DA, Striha A, Collett C, Hockaday A, Jones JR, Kishore B, Garg M, Williams CD, Karunanithi K, Lindsay J, Jenner MW, Cook G, Russell NH, Kaiser MF, Drayson MT, Owen RG, Gregory WM, Morgan GJ; UK NCRI Haemato-oncology Clinical Studies Group. Lenalidomide maintenance vs observation for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:57-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, Conticello C, Catalano L, Corradini P, Siniscalchi A, Magarotto V, Pour L, Carella A, Malfitano A, Petrò D, Evangelista A, Spada S, Pescosta N, Omedè P, Campbell P, Liberati AM, Offidani M, Ria R, Pulini S, Patriarca F, Hajek R, Spencer A, Boccadoro M, Palumbo A. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide vs autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone vs lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1617-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bringhen S, Offidani M, Musto P. Long term outcome of lenalidomide-dexamethasone (Rd) vs melphalan-lenalidomide-prednisone (MPR) vs cyclophosphamide-prednisone-lenalidomide (CPR) as induction followed by lenalidomideprednisone (RP) vs lenalidomide (R) as maintenance in a community-based newly diagnosedmyeloma population. Blood. 2017;130:901. |

| 35. | Magarotto V, Bringhen S, Offidani M. Triplet vs doublet lenalidomide-containing regimens for the treatment of elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016;127(9):1102-1108. Blood. 2018;131:1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, Rajkumar SV, Epstein J, Kahanic SP, Thakuri M, Reu F, Reynolds CM, Sexton R, Orlowski RZ, Barlogie B, Dispenzieri A. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone vs lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:519-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 690] [Article Influence: 86.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Facon T, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, Catalano JV, Belch A, Cavo M, Pinto A, Weisel K, Ludwig H, Bahlis NJ, Banos A, Tiab M, Delforge M, Cavenagh JD, Geraldes C, Lee JJ, Chen C, Oriol A, De La Rubia J, White D, Binder D, Lu J, Anderson KC, Moreau P, Attal M, Perrot A, Arnulf B, Qiu L, Roussel M, Boyle E, Manier S, Mohty M, Avet-Loiseau H, Leleu X, Ervin-Haynes A, Chen G, Houck V, Benboubker L, Hulin C. Final analysis of survival outcomes in the phase 3 FIRST trial of up-front treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2018;131:301-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | McCarthy PL, Hahn T. Strategies for induction, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, consolidation, and maintenance for transplantation-eligible multiple myeloma patients. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | McCarthy PL, Holstein SA. Role of stem cell transplant and maintenance therapy in plasma cell disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:504-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Dimopoulos MA, Delforge M, Hájek R, Kropff M, Petrucci MT, Lewis P, Nixon A, Zhang J, Mei J, Palumbo A. Lenalidomide, melphalan, and prednisone, followed by lenalidomide maintenance, improves health-related quality of life in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients aged 65 years or older: results of a randomized phase III trial. Haematologica. 2013;98:784-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Benboubker L, Dimopoulos MA, Dispenzieri A, Catalano J, Belch AR, Cavo M, Pinto A, Weisel K, Ludwig H, Bahlis N, Banos A, Tiab M, Delforge M, Cavenagh J, Geraldes C, Lee JJ, Chen C, Oriol A, de la Rubia J, Qiu L, White DJ, Binder D, Anderson K, Fermand JP, Moreau P, Attal M, Knight R, Chen G, Van Oostendorp J, Jacques C, Ervin-Haynes A, Avet-Loiseau H, Hulin C, Facon T; FIRST Trial Team. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:906-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Niesvizky R, Flinn IW, Rifkin R, Gabrail N, Charu V, Clowney B, Essell J, Gaffar Y, Warr T, Neuwirth R, Zhu Y, Elliott J, Esseltine DL, Niculescu L, Reeves J. Community-Based Phase IIIB Trial of Three UPFRONT Bortezomib-Based Myeloma Regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3921-3929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Palumbo A, Hajek R, Delforge M, Kropff M, Petrucci MT, Catalano J, Gisslinger H, Wiktor-Jędrzejczak W, Zodelava M, Weisel K, Cascavilla N, Iosava G, Cavo M, Kloczko J, Bladé J, Beksac M, Spicka I, Plesner T, Radke J, Langer C, Ben Yehuda D, Corso A, Herbein L, Yu Z, Mei J, Jacques C, Dimopoulos MA; MM-015 Investigators. Continuous lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1759-1769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 584] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chan HSH, Chen CI, Reece DE. Current Review on High-Risk Multiple Myeloma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2017;12:96-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |