Published online Aug 26, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8742

Peer-review started: March 20, 2022

First decision: April 13, 2022

Revised: April 16, 2022

Accepted: July 20, 2022

Article in press: July 20, 2022

Published online: August 26, 2022

Processing time: 148 Days and 17.2 Hours

The literature on post-hepatectomy bile duct injury (PHBDI) is limited, lacking large sample retrospective studies and high-quality experience summaries. Therefore, we reported a special case of iatrogenic bile duct injury caused by Glissonean pedicle transection with endovascular gastrointestinal anastomosis (endo-GIA) during a right hepatectomy, analyzed the causes of this injury, and summarized the experience with this patient.

We present the case of a 66-year-old woman with recurrent abdominal pain and cholangitis due to intrahepatic cholangiectasis (Caroli's disease). Preoperative evaluation revealed that the lesion and dilated bile ducts were confined to the right liver, with right hepatic atrophy, left hepatic hypertrophy, and hilar translocation. This problem can be resolved by performing a standard right hepatectomy. Although the operation went well, jaundice occurred soon after the operation. Iatrogenic bile duct injury was considered after magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography review, and the second operation were performed 10 d later. During the second operation, it was found that the endo-GIA had damaged the lateral wall of the hepatic duct and multiple titanium nails remained in the bile duct wall. This led to severe stenosis of the duct wall, and could not be repaired. Therefore, the injured bile duct was transected, and a hepatic-jejunal-lateral Roux-Y anastomosis was performed at the healthy part of the left hepatic duct. After this surgery, the patient had a smooth postoperative recovery, and the total bilirubin gradually decreased to normal. The patient was discharged 41 d after operation. No anastomotic stenosis was found at the 6 mo of follow-up.

Not all cases are suitable for endo-GIA transection of Glissonean pedicle, especially in cases of intrahepatic bile duct lesions. PHBDI caused by endo-GIA is very difficult to repair due to extensive ischemia, which requires special attention.

Core Tip: There have been few reports on post-hepatectomy bile duct injury (PHBDI). In this report, we present a case of PHBDI caused by the wrong choice of transection tool, such as endovascular gastrointestinal anastomosis (endo-GIA), which was successfully saved by reoperation. We wanted to draw attention to the fact that not all cases are suitable for endo-GIA transection of Glissonean pedicle.

- Citation: Zhao J, Dang YL. When should endovascular gastrointestinal anastomosis transection Glissonean pedicle not be used in hepatectomy? A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(24): 8742-8748

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i24/8742.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i24.8742

There have been more reports on iatrogenic bile duct injuries (BDIs) after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), i.e., LCBDIs, although its incidence has been reduced to 0.3%-0.7%[1]. However, the incidence of post-hepatectomy bile duct injury (PHBDI) is as high as 3.6%-17%[2], accounting for one-third of the post-hepatectomy mortality[3], and more attention should be paid to this type of injury to decrease its occurrence[4]. With the increasing popularity of laparoscopic and robotic hepatectomy worldwide[5,6] and the increasing reliance on the use of energy devices and Tric-stapleTM, as well as the difficulty in determining the spatial relationship between catheters due to the lack of complete stereoscopic vision and tactile feedback in the laparoscopic field of vision, the true incidence of PHBDI may be higher[7]. However, there is still a lack of large sample clinical studies and high-quality experience summaries specifically for its cause analysis and prevention strategies. Thus, we reported a specific case of PHBDI caused by Glissonean pedicle transection with endovascular gastrointestinal anastomosis (endo-GIA) during right a hemi-hepatectomy, analyzed its causes, and summarized the experience with this patient.

A 66-year-old Chinese female presented with recurrent abdominal pain for 20 years and fever for 1 wk.

The patient began to experience intermittent dull pain in the upper abdomen more than 20 years ago, with no obvious inducement, and spontaneously relieved by rest. Initially, no other concomitant symptoms were found, but the pain occurred 1-2 times per month. In the past 2 years, the frequency of abdominal pain increased to about 1-2 times a week. The patient developed chills and a fever 1 wk ago, with the highest body temperature of 38.3 ℃, which were relieved after oral administration of antipyretic and analgesic drugs. No jaundice was evident.

The patient was diagnosed as type 2 diabetes and hypertension 2 years ago, which has been controlled well with oral medication.

The patient had no special personal and family history.

At admission, the patient’s consciousness was clear, with a body temperature of 37.3 ℃, and a blood pressure on 145/85 mmHg, without skin and sclera jaundice. The abdomen was soft and flat, with percussive pain in the right upper quadrant and liver area, without tenderness or rebound pain. Murphy’s sign was negative.

Laboratory tests indicated that only alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GTP) were slightly elevated at admission, with normal infection indicators, tumor markers, and total bilirubin (TBIL) (Table 1).

| On admission | Day 3 postoperatively | Day 8 postoperatively | Day 13 postoperatively (day 3 after re-operation) | Day 35 postoperatively (day 25 after re-operation) | |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 4.53 | 12.81 | 13.21 | 16.3 | 6.41 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.2 | 11.9 | 12.9 | 12 | 13.5 |

| Plt (× 109/L) | 210 | 243 | 288 | 179 | 231 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 17.6 | 68 | 158.7 | 135.1 | 15.6 |

| AST (U/L) | 17 | 891 | 780 | 860 | 14 |

| ALT (U/L) | 20 | 706 | 612 | 778 | 13 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 84 | 349 | 694 | 589 | 20 |

| ALP (U/L) | 75 | 344 | 481 | 450 | 57 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 42.4 | 34.5 | 31.6 | 29.7 | 39.6 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 65.1 | 58 | 38.6 | 31.5 | 68 |

| PT (s) | 10.2 | 11.5 | 14.6 | 13.1 | 9.8 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.098 | 89.1 | 135.7 | 171.6 | 0.086 |

| CA19-9 (μ/mL) | 17.7 | ||||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.3 |

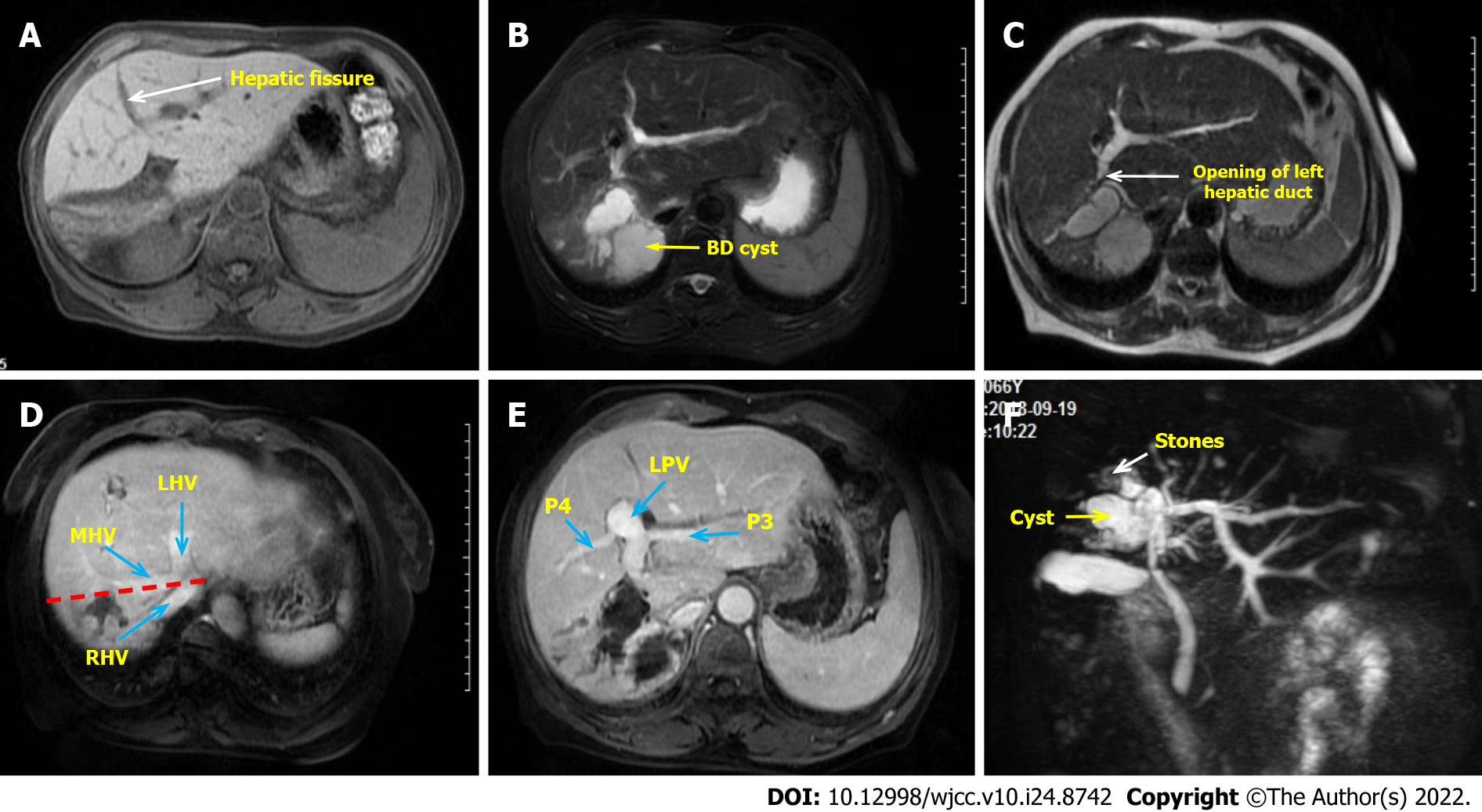

Contrast-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a dilated bile duct in right liver with a large cyst occupying the beginning of the right anterior and posterior hepatic ducts, accompanied by rights liver atrophy, left liver hyperplasia, and counterclockwise hilar translocation (Figure 1A and B). The opening of left hepatic duct was very close to the cyst (Figure 1C), the right portal vein branch was not clearly seen, with no variation of extrahepatic bile duct and other blood vessels (Figure 1D and E). The peripheral bile ducts were full of stones (Figure 1F). According to the preoperative imaging evaluation, standard right hepatectomy could resolve this lesion.

According to clinical and imaging features, intrahepatic cholangiectasia (Caroli's disease, Todani type-V) with recurrent cholangitis, atrophy-hypertrophy complex, and hilar translocation was considered.

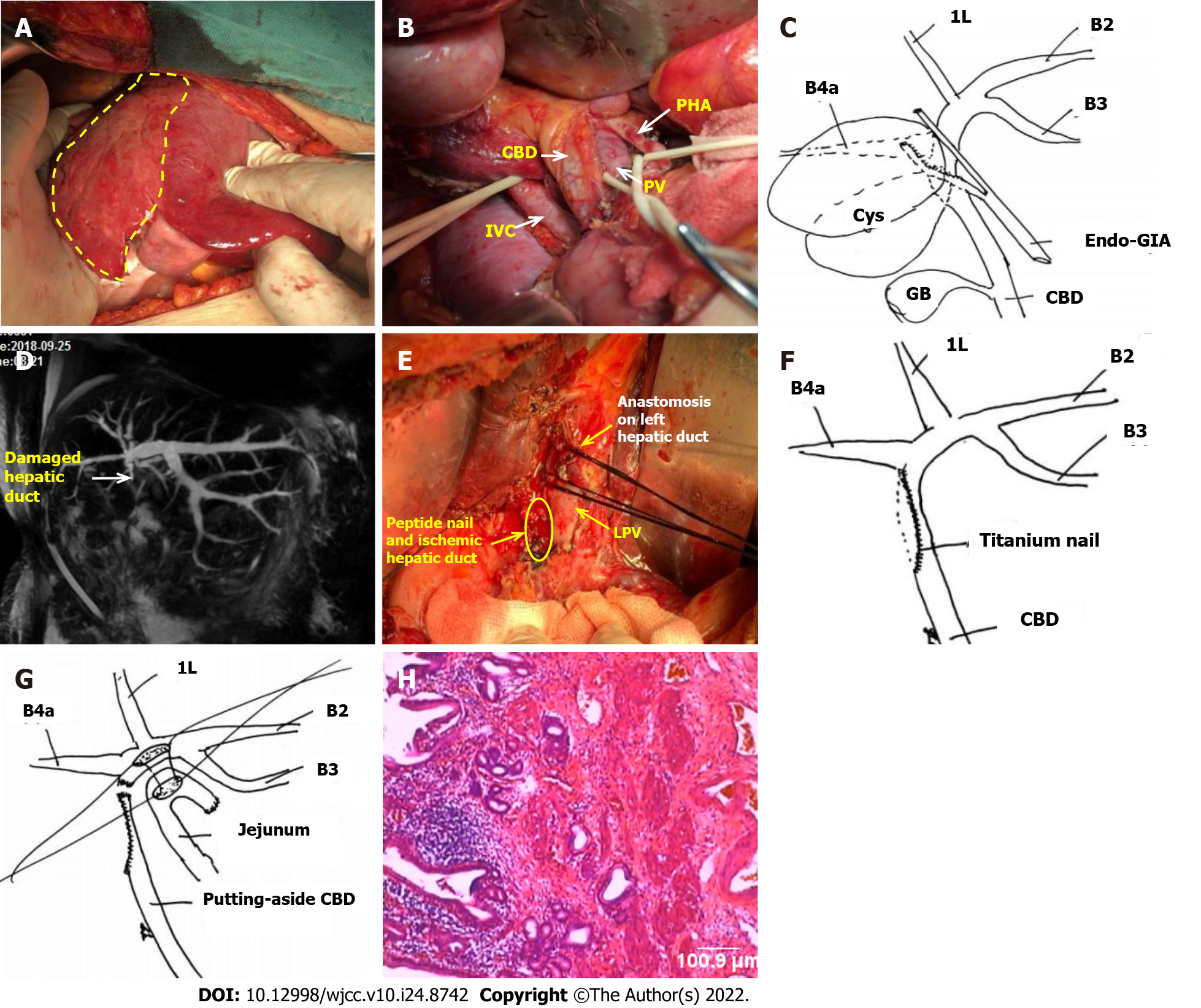

After preoperative evaluation, it was considered that the lesion was confined to the right liver and could be resolved by standard right hepatectomy, so the first operation was performed. During the operation, obvious fibrosis and atrophy were found in the right liver (Figure 2A). The diseased bile duct was close to the bifurcation of the left and right hepatic ducts, and the extrahepatic bile duct was slender. The initial part of the right hepatic duct was first separated from extrasheathical dissection method, the right hepatic duct was then transected with endo-GIA (Figure 2B and C), and finally a standard right hepatectomy was performed along the demarcation line of the liver surface. No abnormalities were found during the operation. Postoperative reexamination found a gradual increase in TBIL, but there were no significant change in white blood cells (Table 1), and the patient did not complain of any special uncomfortable feeling. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was reexamined on the 5th postoperative day and no extrahepatic bile duct was found, and the left hepatic duct was dilated compared with the operation before (Figure 2D). At this point, we realized that a biliary tract injury had occurred, so a second operation was performed on the 10th day. During the second operation, the lateral wall of the hepatic duct damaged by endo-GIA was found, which had led to severe stenosis and occlusion. Residual titanium nails could be seen in the damaged bile duct wall, leading to locally significant inflammatory edema and ischemia (Figure 2E and F). The damage was about 4 cm long, which could not be repaired at this location. The portal vein and the hepatic artery were not damaged. Therefore, the injured hepatic duct was directly transected, the main trunk of the left hepatic duct was dissected and exposed, and the left hepatic duct and jejunum side-by-side anastomosis (Roux-Y anastomosis) was completed (Figure 2G). The patient recovered smoothly, and no additional complications occurred after re-operation. TBIL and γ-GTP levels gradually decreased, and liver function gradually improved (Table 1). Postoperative pathology found chronic inflammation of the bile duct wall, but no malignant cells were found (Figure 2H). The patient was discharged on the 41st day after operation.

After half a year of follow-up, the patient had no abdominal pain or fever, no anastomotic stenosis, and normal liver functions. The patient was later lost due to coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

Iatrogenic bile duct injury is a permanent pain for hepatobiliary surgeons[8]. However, the understanding of BDI is often limited to LCBDI, rather than PHBDI, as few scholars pay attention to this injury. Both injuries have significant differences in injury causes, risk factors, injury characteristics, clinical classification, preventive principles, and treatment methods[4]. The reviews of the literature on the clinical characteristics of PHBDI show that it mostly occurs to the high bile duct (the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts and above) and is prone to vascular injury[9-10]. Injuries to laparoscopic hepatectomy are often related to the use of endo-GIA/Endo-Cutter, and energy equipment, with difficult repair and poor prognosis[9]. Clinical manifestations are hyperbilitary stenosis, obstruction, bile duct leakage, and bile duct bleeding. Most patients, already complicated with basic liver diseases (cirrhosis, cholangitis, liver cancer, etc.), can develop severe abdominal infection, liver failure, and even death[11].

The risk factors of PHBDI that should be a major concern for liver surgeons include[7,12]: (1) Variations in hilar bile duct anatomy, such as right anterior hepatic duct opening in left hepatic duct or right posterior hepatic duct low or ecotone confluence in hepatic duct or gallbladder duct[3]; (2) The combination of hepatic atrophy and hyperplasia, as well as hilar translocation, which usually occurs in benign biliary lesions (such as hepatolithiasis and Caroli's disease), past hepatectomy, and mass effect of large hilar tumors; (3) Intraoperative overstretching causing the displacement of the reserved lateral bile duct; (4) Improper position of transverse hepatic pedicle; (5) Complex and difficult operations or combined hilar lymph node dissections that are easy to cause injury; (6) Blind clipping or disconnection performed in case of intraoperative misjudgment or deviation from the resection plane; and (7) Incorrect use of energy devices (such as ultrasound scalpel, electrocoagulating blood stopper, etc.) and endo-GIA.

The causes of the injury in our patient are various, including objective unfavorable factors, such as the lesion duct’s location close to the reserved side bile duct and right liver atrophy leading to hilar translocation. However, the root cause of this case was the wrong choice of transection tools, such as endo-GIA, rather than the wrong process when using it. Initially, during the operation, the author and assistants repeatedly remind each other not to accidentally hurt the healthy side bile duct, and therefore, the injury was not likely caused by carelessness. Second, because the lesion bile duct of cystic dilation was too close to the common hepatic duct, there was no "safe boundary" when it was transected. Because endo-GIA's fuselage itself has a certain width, the tissue inside this objectively small width is invisible when transected. Predictably, in this particular type of case, if endo-GIA is used to transected the Glissonean pedicle, it is expected that there is a higher chance that BDI will occur. This is the contradiction between "removal of lesions thoroughness" and "surgical safety".

Therefore, the important points that we learned from this particular case include: (1) It is necessary to transect the Glissonean pedicle in or as close as possible to the liver, whether the Glissonean pedicle extrahepatic or intrahepatic dissection technology is adopted[13-15]; (2) Endo-GIA should not be selected for transection of the Glissonean pedicle in hepatectomy cases involving intrahepatic bile duct diseases, as we need to treat the intrahepatic bile duct separately to prevent the bile duct injury. It should not be recommended for cases such as intrahepatic cholangiectasia, intrahepatocholic stones, and Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially the special types of lesion bile ducts very close to the reserved side bile duct[3]; (3) In particular, it should be noted that the reason why the use of endo-GIA transection of the Glissonean pedicle is less accurate than ligation and suture is that the fuselage of gastrointestinal anastomosis has a certain width, and it is necessary to reserve a certain safety boundary during the operation to prevent the damage of bile duct on the reserved side; and (4) Based on the above discussion, we believe that a better way to avoid this situation is to replace the endo-GIA with a manual suture method.

Another important topic we would like to discuss regarding this case is that the damage to the sidewall of the bile duct caused by the endo-GIA is very difficult to reconstruct. The experience and methods we have accumulated in the past for the repair and reconstruction of the bile duct after LCBDI are totally inapplicable. The root cause was dense peptide nails that caused damage to the bile ducts, which led to an unimaginable range of ischemia, as shown in Figure 2E. If it is repaired by local plastic surgery or gastrointestinal muscle flaps, the consequences must be stenosis. Therefore, only a higher position of the hepatic duct and jejunum anastomosis can solve the problem. This opinion has not been mentioned in previous literature.

In conclusion, we would like to remind that the use of endo-GIA should also have certain indications and contraindications (it is usually safe, but not always). We need to understand endo-GIA's advantages and disadvantages, as well as a learning curve and operational experiences. Selecting the right patient with the right device is a key concern, and sometimes safety is more important than "radical resection". The treatment of PHBDI caused by Endo-GIA is difficult, and we may provide a reference to the successful treatment of this case.

Not all cases are suitable for endo-GIA transection of the Glissonean pedicle, especially in cases of intrahepatic bile duct lesions. PHBDI caused by Endo-GIA is very difficult to repair due to extensive ischemia, which requires special attention.

The authors thank Dr. Dang YL, Department of Obstetrics, The First People's Hospital of Yunnan Province, for participating in the discussion and conclusion.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ghimire R, Nepal; Kumar S, India S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yan JP

| 1. | Marino MV, Mirabella A, Guarrasi D, Lupo M, Komorowski AL. Robotic-assisted repair of iatrogenic common bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Surgical technique and outcomes. Int J Med Robot. 2019;15:e1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van Gulik TM. Prevention of biliary leakage after partial liver resection using topical hemostatic agents. Dig Surg. 2007;24:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fragulidis G, Marinis A, Polydorou A, Konstantinidis C, Anastasopoulos G, Contis J, Voros D, Smyrniotis V. Managing injuries of hepatic duct confluence variants after major hepatobiliary surgery: an algorithmic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3049-3053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boonstra EA, de Boer MT, Sieders E, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Slooff MJ, Porte RJ. Risk factors for central bile duct injury complicating partial liver resection. Br J Surg. 2012;99:256-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Edwin B, Nordin A, Kazaryan AM. Laparoscopic liver surgery: new frontiers. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:54-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morise Z. Developments and perspectives of laparoscopic liver resection in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Today. 2019;49:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zheng SG. Characteristics and prevention strategies of bile duct injury during laparoscopic hepatectomy. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2018;38:1012-1014. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Dai HS, Liang L, Zhang CC, Cheng ZJ, Peng YH, Zhang YM, Geng XP, Qin HJ, Wang K, Chen W, Yu C, Wang LF, Lau WY, Zhang LD, Zheng SG, Bie P, Shen F, Wu MC, Chen ZY, Yang T. Impact of iatrogenic biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy on surgeon's mental distress: a nationwide survey from China. HPB (Oxford). 2020;22:1722-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sakamoto K, Tamesa T, Yukio T, Tokuhisa Y, Maeda Y, Oka M. Risk Factors and Managements of Bile Leakage After Hepatectomy. World J Surg. 2016;40:182-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lam CM, Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST. Biliary complications during liver resection. World J Surg. 2001;25:1273-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ninomiya M, Tomino T, Matono R, Nishizaki T. Clip on Staple Method to Prevent Bile Leakage in Anatomical Liver Resection Using Stapling Devices. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:401-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang HC, Huang SY, Wu CC, Chou CM. Delayed repair of post-hepatectomy bile duct injury by ducto-jejunostomy directly through a percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage tract: An easy alternative. Asian J Surg. 2021;44:926-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim JH, Choi JW. Intrahepatic Glissonian Approach to the Ventral Aspect of the Arantius Ligament in Laparoscopic Left Hemihepatectomy. World J Surg. 2019;43:1303-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lubikowski J, Piotuch B, Stadnik A, Przedniczek M, Remiszewski P, Milkiewicz P, Silva MA, Wojcicki M. Difficult iatrogenic bile duct injuries following different types of upper abdominal surgery: report of three cases and review of literature. BMC Surg. 2019;19:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Scuderi V, Troisi RI. Tissue management with tri-staple technology in major and minor laparoscopic liver resections. Int Surg. 2014;99:606-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |