Published online Jun 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5463

Peer-review started: October 21, 2021

First decision: February 15, 2022

Revised: March 7, 2022

Accepted: April 20, 2022

Article in press: April 20, 2022

Published online: June 6, 2022

Processing time: 224 Days and 1.7 Hours

Visceral leishmaniasis related-hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (VL-HLH) is a hemophagocytic syndrome caused by Leishmania infection. VL-HLH is rare, especially in nonendemic areas where the disease is severe, and mortality rates are high. The key to diagnosing VL-HLH is to find the pathogen; therefore, the Leishmania must be accurately identified for timely clinical treatment.

We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data, laboratory examination results, and bone marrow cell morphology of two children with VL-HLH diagnosed via bone marrow cell morphology at Kunming Children’s Hospital of Yunnan, China. Both cases suspected of having malignant tumors at other hospitals and who were unresponsive to treatment were transferred to Kunming Children’s Hospital. They are Han Chinese girls, one was 2 years old and the other one is 9 mo old. They had repeated fevers, pancytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia over a long period and met the HLH-2004 criteria. Their HLH genetic test results were negative. Both children underwent chemotherapy as per the HLH-2004 chemotherapy regimen, but it was ineffective and accompanied by serious infections. We found Leishmania amastigotes in their bone marrow via morphological examination of their bone marrow cells, which showed hemophagocytic cells; thus, the children were diagnosed with VL-HLH. After being transferred to a specialty hospital for treatment, the condition was well-controlled.

Morphological examination of bone marrow cells plays an important role in diagnosing VL-HLH. When clinically diagnosing secondary HLH, VL-HLH should be considered in addition to common pathogens, especially in patients for whom HLH-2004 chemotherapy regimens are ineffective. For infants and young children, bone marrow cytology examinations should be performed several times and as early as possible to find the pathogens to reduce potential misdiagnoses.

Core Tip: This study started with the morphology of bone marrow cells, finding the pathogen from the cells, and successfully diagnosed two cases of visceral leishmaniasis related-hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (VL-HLH), which was then compared and analyzed with HLH. The key criterion for differential diagnosis of VL-HLH is to find the pathogen in bone marrow cells. This has great guiding significance for clinical laboratory diagnosis and clinical treatment.

- Citation: Shi SL, Zhao H, Zhou BJ, Ma MB, Li XJ, Xu J, Jiang HC. Diagnostic value of bone marrow cell morphology in visceral leishmaniasis-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(16): 5463-5469

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i16/5463.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i16.5463

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS), also known as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), is divided into primary and secondary forms. The etiology of secondary HLH is complex; it can be caused by infection, malignant tumors, and autoimmune diseases. Visceral leishmaniasis-related HLH (VL-HLH) is very rare in childhood, especially in nonendemic areas. The disease is severe with high mortality rates of up to 100% without early diagnosis and treatment[1,2]. Therefore, the leishmaniasis-associated pathogen must be rapidly and accurately identified for clinical and timely treatment. Here, we report two young patients with VL-HLH diagnosed via bone marrow cell morphology at the Children’s Hospital of Kunming, Yunnan, China in the past 5 years.

Case 1: Repeated irregular fever lasting 3 mo and decreased peripheral blood cells.

Case 2: Repeated irregular fever for 1 mo and thrombocytopenia found for 2 d.

Case 1: The patient had recurrent and irregular fever lasting 3 mo and reaching 39–40 °C. After the appearance of fever of symptoms, she was hospitalized at a local hospital for 2 mo. Her blood counts decreased progressively, and she underwent symptomatic and supportive treatment, including meropenem, vancomycin, piperacillin, tazobactam, gamma-globulin, methylprednisolone, cefoperazone, sulbactam, Tienam, and a blood transfusion. The clinical symptoms of the child did not improve, and the child was still feverish. After the above symptomatic treatment, the clinician suspected acute leukemia. She continued to have repeated fevers, coughing with sputum, abdominal distension, anorexia, and fatigue.

Case 2: The patient had repeated irregular fever lasting for 1 mo and reaching 39–40 °C. Her peripheral blood platelet decreased. She did not recover at her local hospital and was thus transferred to Kunming Children’s Hospital.

Case 1: The patient continued to have repeated fevers, coughing with sputum, abdominal distension, anorexia, and fatigue. She had a history of mosquito bites and contact with a domestic dog 1 mo before onset as well as a history of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related hemophagocytic syndrome in April 2017.

Case 2: None.

Both children had enlarged liver and spleen.

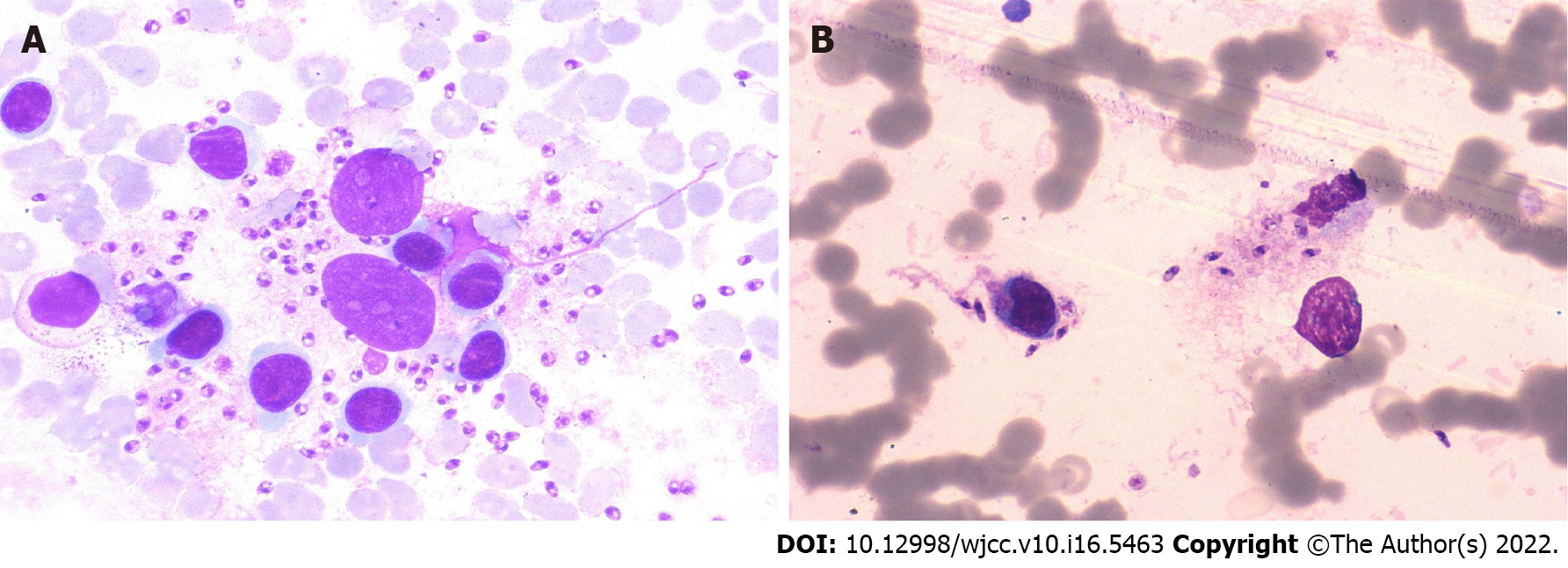

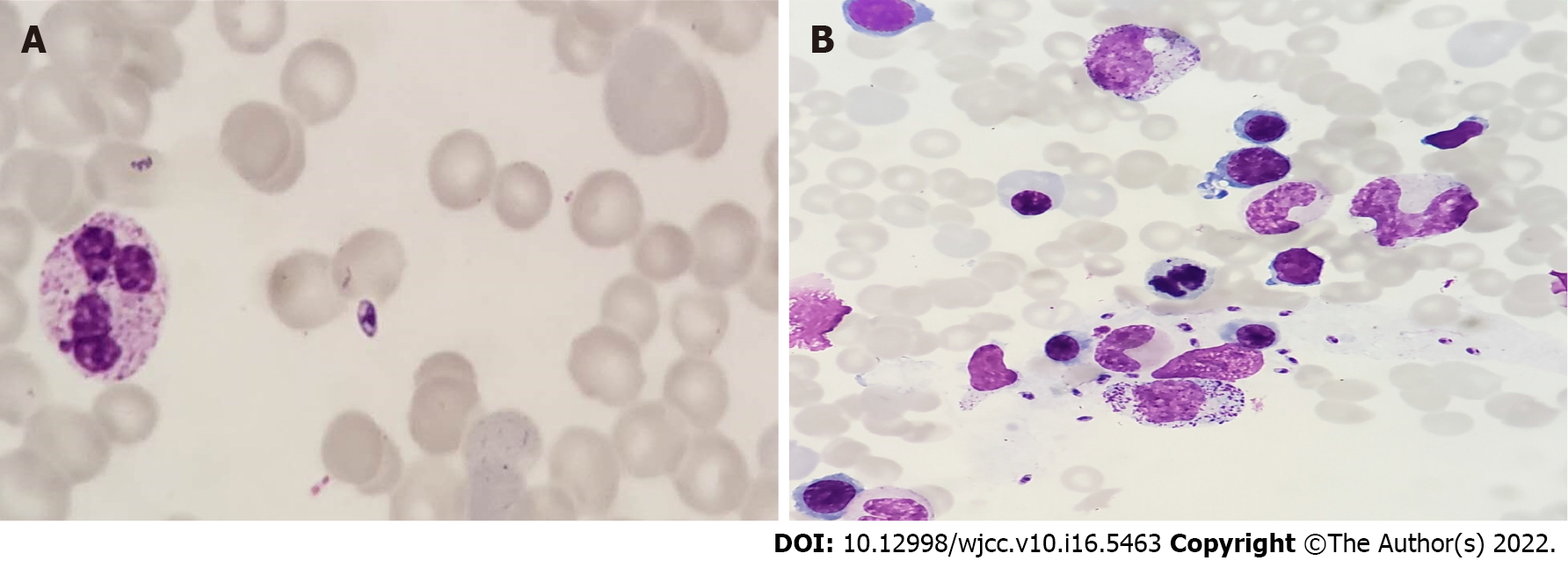

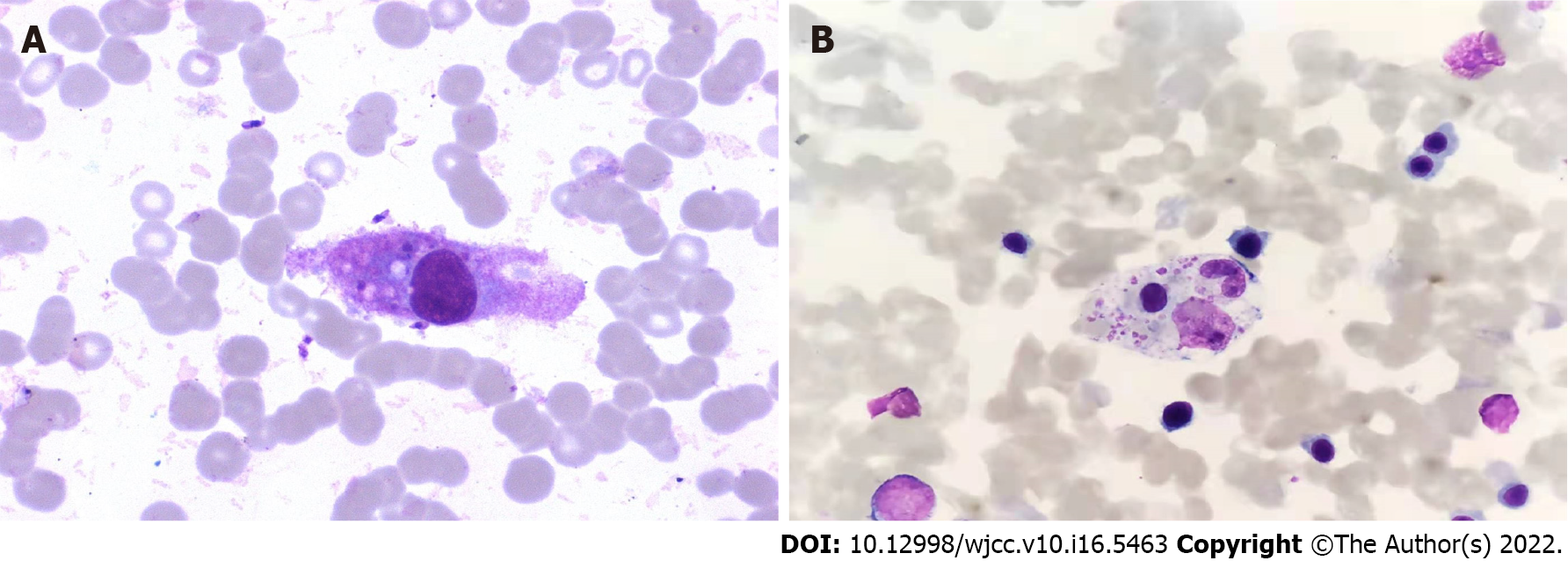

The results of the examination for related pathogens revealed the Leishmania amastigotes in the bone marrow of both patients (Figures 1 and 2). Leishmania amastigotes can be seen inside and outside of phagocytes, and their shape was round and oval, with a diameter of about 2 to 5 μm. The cytoplasm was light blue, with a large round nucleus inside, and the nucleus was purplish red. Beside the nucleus, a small, rod-shaped, and darkly colored moving matrix can be seen. The morphological characteristics were consistent with those of Leishmania amastigotes. Hemophagocytic cells were easily seen in the bone marrow of both patients (Figure 3). One child was infected with the EBV but tested negative for other pathogens (Table 1).

| Etiological examination | Case 1 | Case 2 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 2.82 x 103 | Negative |

| K39 tests | Positive | Positive |

| Cytomegalovirus | Negative | Negative |

| Rubella virus | Negative | Negative |

| Influenza virus | Negative | Negative |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Negative | Negative |

| Adenovirus | Negative | Negative |

| Antihemolytic streptococcus O | Normal | Normal |

| Rheumatoid factor | Normal | Normal |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-nuclear antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Legionella pneumophila | Negative | Negative |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia | Negative | Negative |

| Q fever, rickettsia | Negative | Negative |

| Blood culture | Negative | Negative |

| Bone marrow cytology | ||

| Leishmania amastigotes | Positive | Positive |

| Hemophagocytic cells | Easily seen | Easily seen |

| Hemophagocytic-related genes | Negative | Negative |

| Acute and chronic leukemia immunophenotyping | Negative | Negative |

The hemoglobin and platelets decreased in both children, and the infection indexes such as high-sensitivit C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and procalcitonin were increased on admission. According to HLH-2004 chemotherapy regimen, after 14 d of treatment, the clinical symptoms and related detection indicators such as routine blood parameters, infection indicators, and other detection items of the two children did not improve. However, the clinical symptoms improved, routine blood parameters, infection indexes, and liver function returned to normal, and no Leishmania was found in their bone marrow, after 21 d of sodium stibogluconate (SSG) treatment (Table 2).

| Detection index | Normal range | On admission | After HLH-2004 chemotherapy regimen treatment for 14 d | After SSG treatment for 21 d | |||

| Characteristic | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 1 | Case 2 | |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | 4.0–10.0 | 2 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 5.8 |

| Red blood cell count (× 1012/L) | 4.0–5.5 | 2 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.83 | 4.08 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 97-141 | 69 | 94 | 91 | 97 | 112 | 119 |

| Platelet count (× 109/L) | 100–300 | 35 | 44 | 66 | 28 | 118 | 110 |

| High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.5-10.0 | 151.8 | 198.3 | 85.3 | 16.3 | 5.9 | 2.3 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0-0.25 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ferritin (μg/L) | 7.0-142.0 | 40000 | 69445 | 1886 | 2000 | 128 | 116 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.0-4.0 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 0-40.0 | 75 | 178 | 41 | 149 | 39 | 28 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 55.0-76.0 | 62.2 | 55.7 | 62.2 | 65.1 | 64.2 | 66.1 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 39.0-54.0 | 24.7 | 29.2 | 24.7 | 30.9 | 40.5 | 42.7 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 12.0-34.0 | 37.5 | 36.5 | 37.5 | 34.2 | 23.7 | 23.4 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 109.0-245.0 | 2700 | 2648 | 256 | 1803.8 | 238 | 226 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.70-2.30 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

Abdominal ultrasound showed enlarged liver and spleen in both children.

Both children were diagnosed with VL-HLH.

Both children were treated with SSG (manufactured by Shandong Xinhua Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) at 200 mg antimony/kg. The total amount was divided into six doses, intramuscular injection or intravenous injection twice a week, a course of 3 wk (6 doses). The two patients’ conditions quickly improved.

No Leishmania was found in their bone marrow after 3 wk of treatment with the above regimen. Both patients recovered and were discharged.

HLH is a life-threatening disease caused by excessive inflammation and multiple organ dysfunction, resulting in uncontrollable lymphocyte and macrophage activation and proliferation[3]. HLH is divided into primary and secondary forms. Infection is the most common cause of secondary HLH[4]. VL-HLH is very rare in childhood and has a high mortality rate if not diagnosed and treated early[1].

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is caused by Leishmania, common pathogens include Leishmania donovani, Leishmania infantum, and Leishmania tropica, and phlebotomine sandflies are the main transmission vector. The infectious agents of this disease are mainly the patients and sick dogs. The disease is transmitted between humans and animals via blood sucking by phlebotomine sandflies[5-7]. The disease has obvious regional characteristics. VL is scattered throughout six western provinces in China and Xinjiang, Gansu, Sichuan, and Shaanxi[8]. The two cases reported herein were from Weining County, Guizhou, and Yunnan after moving from Zhouqu, Gansu. Both children had lived in epidemic areas and had histories of phlebotomine sandfly bites from June to September (the sandfly breeding season) before disease onset. Weining County in Guizhou and Zhouqu County in Gansu Province are both areas where leishmaniasis was spreading[8]. The epidemiological histories of both children were clear.

Both children had long-term irregular fevers, with the highest body temperature exceeding 40 ℃, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly. Because of these clinical manifestations, they were initially misdiagnosed as having malignant hematological diseases. Neither of them recovered after long-term treatment with drugs at other hospitals, and both had severe infections. VL-HLH is easily misdiagnosed in nonendemic areas because VL manifestations are very similar to those of hematological malignancies. VL symptoms also include a long-term irregular fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia. Additionally, VL has rapid onset and progression. Early symptoms are atypical with many complications; thus, it is easily misdiagnosed[9], especially when combined with EBV infections, leading clinicians to think that it is EBV-associated HLH. Many clinicians have insufficient knowledge and no clinical experience with VL, especially in nonendemic areas. Furthermore, laboratory physicians often lack knowledge of the Leishmania. Due to the morphology of Leishmania amastigotes and platelets is very similar, laboratory physicians may mistake them as platelets; they are also easily engulfed by phagocytes. At the same time, these phagocytes may also contain platelets, red blood cells, and white blood cells, and if the laboratory technicians are unfamiliar with Leishmania amastigotes or do not read the results carefully, they may mistake them for platelets. Many reports have found that kala-azar is often misdiagnosed owing to clinicians’ and technicians’ lack of knowledge of Leishmania amastigotes[10]. The morphologies of Leishmania, Penicillium marneffei, and histoplasma have many similarities and are easily confused. Clinicians and technicians must be familiar with the morphological characteristics of various pathogens and the differences between them. No Leishmania amastigotes were found in either child via bone marrow cell morphology at the previous hospital; thus, the children were misdiagnosed with hematological malignancies. The key to diagnosing these children is to detect the Leishmania amastigotes via bone marrow cell morphology combined with their epidemiological histories. To diagnose HLH secondary to kala-azar, finding the pathogen in the bone marrow is the most reliable diagnostic criterion.

VL-HLH-associated mortality is relatively high. If HLH treatment is ineffective, clinicians should consider whether the HLH is secondary to VL. Both patients in this study underwent 14 d of chemotherapy according to the HLH-2004 chemotherapy regimen, but the chemotherapeutic effect was unsatisfactory, their clinical symptoms did not significantly improve, and their liver and kidney function did not recover as per the related infection indicators. After the disease was clearly diagnosed, they received the recommended treatment, and the disease was quickly controlled. Both patients recovered and were discharged from the hospital. When clinically diagnosing HLH, clinicians should actively search for the cause. If standard treatment for HLH is ineffective, detailed epidemiological histories should be taken, bone marrow cytology examinations should be performed quickly, and HLH secondary to VL should be ruled out.

In summary, bone marrow cell morphological examinations play a vital role in diagnosing VL-HLH. When secondary HLH is diagnosed clinically, common pathogens and VL-HLH should both be considered, especially in infants and young children who could not be treated satisfactorily as per the HLH-2004 regimen. Detailed epidemiological histories should be taken, and bone marrow cytology should be re-examined multiple times as soon as possible to find the pathogen and reduce misdiagnoses. Clinicians and technicians should be familiar with the morphological characteristics of Leishmania to provide timely and accurate diagnoses.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Parasitology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Reviewer: De Souza JN, Brazil; El Chazli Y, Egypt; Khodabandeh M, Iran; Portillo R, Czech Republic S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Sundar S, Singh OP. Molecular Diagnosis of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Mol Diagn Ther. 2018;22:443-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3602] [Article Influence: 200.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:233-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Janka G, Imashuku S, Elinder G, Schneider M, Henter JI. Infection- and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndromes. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:435-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang JY, Gao CH, Yang YT, Chen HT, Zhu XH, Lv S, Chen SB, Tong SX, Steinmann P, Ziegelbauer K, Zhou XN. An outbreak of the desert sub-type of zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis in Jiashi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, People's Republic of China. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:331-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lu HG, Zhong L, Guan LR, Qu JQ, Hu XS, Chai JJ, Xu ZB, Wang CT, Chang KP. Separation of Chinese Leishmania isolates into five genotypes by kinetoplast and chromosomal DNA heterogeneity. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:763-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang JY, Ha Y, Gao CH, Wang Y, Yang YT, Chen HT. The prevalence of canine Leishmania infantum infection in western China detected by PCR and serological tests. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zheng C, Wang L, Li Y, Zhou XN. Visceral leishmaniasis in northwest China from 2004 to 2018: a spatio-temporal analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao S, Li Z, Zhou S, Zheng C, Ma H. Epidemiological Feature of Visceral Leishmaniasis in China, 2004-2012. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:51-59. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Schwing A, Pomares C, Majoor A, Boyer L, Marty P, Michel G. Leishmania infection: Misdiagnosis as cancer and tumor-promoting potential. Acta Trop. 2019;197:104855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |