Published online Apr 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3472

Peer-review started: July 12, 2021

First decision: November 19, 2021

Revised: December 2, 2021

Accepted: February 27, 2022

Article in press: February 27, 2022

Published online: April 16, 2022

Processing time: 270 Days and 8.3 Hours

Aortic coarctation (CoA) is usually confused with interrupted aortic arch (IAA), especially adult type A interrupted aortic arch, due to their similar anatomical location. Although the main difference between them is whether arterial lumen exhibits continuity or not, the clinical manifestations are similar and connection exists between them. Adult type A IAA is considered as an extreme form of CoA, which is complete discontinuity of aortic function and lumen caused by degenerative arterial coarctation. This paper reports two cases (interrupted aortic arch and severe aortic coarctation) to analyze the difference and similarity between them.

The two cases of patients presented with hypertension for many years. Computed tomography angiography showed that the aortic arch and descending aorta were discontinuous or significantly narrowed with extensive collateral flow. The IAA patient refused surgical treatment and blood pressure could be controlled with drugs. While the CoA patient underwent stent implantation because of uncontrollable hypertension, the blood flow recovered smoothly and the blood pressures at both ends of the stenosis returned to normal after surgery.

Adult type A IAA and CoA have difference and similarity, and type A IAA is associated with CoA to a certain extent. The treatment method should be chosen based on the patient's clinical symptoms rather than the severity of the lesion.

Core Tip: According to the characteristics of aortic coarctation and interrupted aortic arch, this paper highlights the difference and similarity between them. The treatment method should be based on the patient's clinical symptoms rather than the severity of the lesion.

- Citation: Ren SX, Zhang Q, Li PP, Wang XD. Difference and similarity between type A interrupted aortic arch and aortic coarctation in adults: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(11): 3472-3477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i11/3472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i11.3472

Interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a congenital malformation disease with loss of continuity between the aortic arch and descending aorta, accounting for about 1% of congenital heart diseases[1]. According to the location of the dissection, it is divided into three types[2]: The dissection located at the distal to the left subclavian artery origin (type A); that located between the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery (type B); and that between the brachiocephalic trunk and the left common carotid artery (type C). Type A accounts for approximately 79% of adult IAA cases[3], without the complications associated with type B such as ventricular septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus[1,4-6]. Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is defined as a discrete stenosis of the aorta usually located in the area of the ligamentum arteriosum, with a higher incidence of 6%-8% than IAA[3]. To investigate if there are any difference and similarity between adult type A IAA and CoA, cases of both types were reported in this study.

A 54-year-old woman presented to the hospital with chief complaints of discomfort in right waist and abdominal pain for 1 wk. And a 61-year-old female patient, with tiredness and dizziness, was diagnosed with CoA during physical examination 1 year ago.

The medical history was notable for hypertension and the right renal cyst in Case 1. And the described patient in Case 2 was diagnosed with CoA during physical examination 1 year ago with tiredness and dizziness.

The first woman in Case 1 had hypertension for 8 years. The second patient in Case 2 with a history of hypertension for 30 years had the highest blood pressure of 190/100 mmHg, and a clear medical history of thyroidectomy and coronary artery stenosis.

In Case 1, continuous murmurs were heard on the chest and back during auscultation. The blood pressure was monitored after taking the medication, and the left upper and left lower limb blood pressure was 145/77 mmHg and 120/64 mmHg, respectively. The dorsalis pedis arteries were thin and weak. In Case 2, the upper limb pressure was higher than the lower limb pressure.

Laboratory examination indicated the following in Case 1: Uric acid, 412 μmol/L; triacylglycerol 1.95mmol/L.; and glucose, 5.5 mmol/L.

Laboratory examination indicated the following in Case 2: Urea, 3.25 mmol/L; creatinine, 50.8 μmol/L; cholesterol, 3.94 mmol/L; alanine aminotransferase, 19 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 23 U/L; and glucose, 4.81 mmol/L.

Urinalysis, coagulation tests, complete blood count, and infection marker tests did not reveal any obvious abnormalities in either patient.

Case 1: Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed complete right bundle branch block and T wave change. Color Doppler echocardiography displayed a normal right atrium and right ventricle, and an enlarged left atrium and left ventricle. The aortic arch and the distal to the left subclavian artery were discontinuous, and numerous collateral branches existed around the descending aorta. The flow of the abdominal aorta showed a small slow wave.

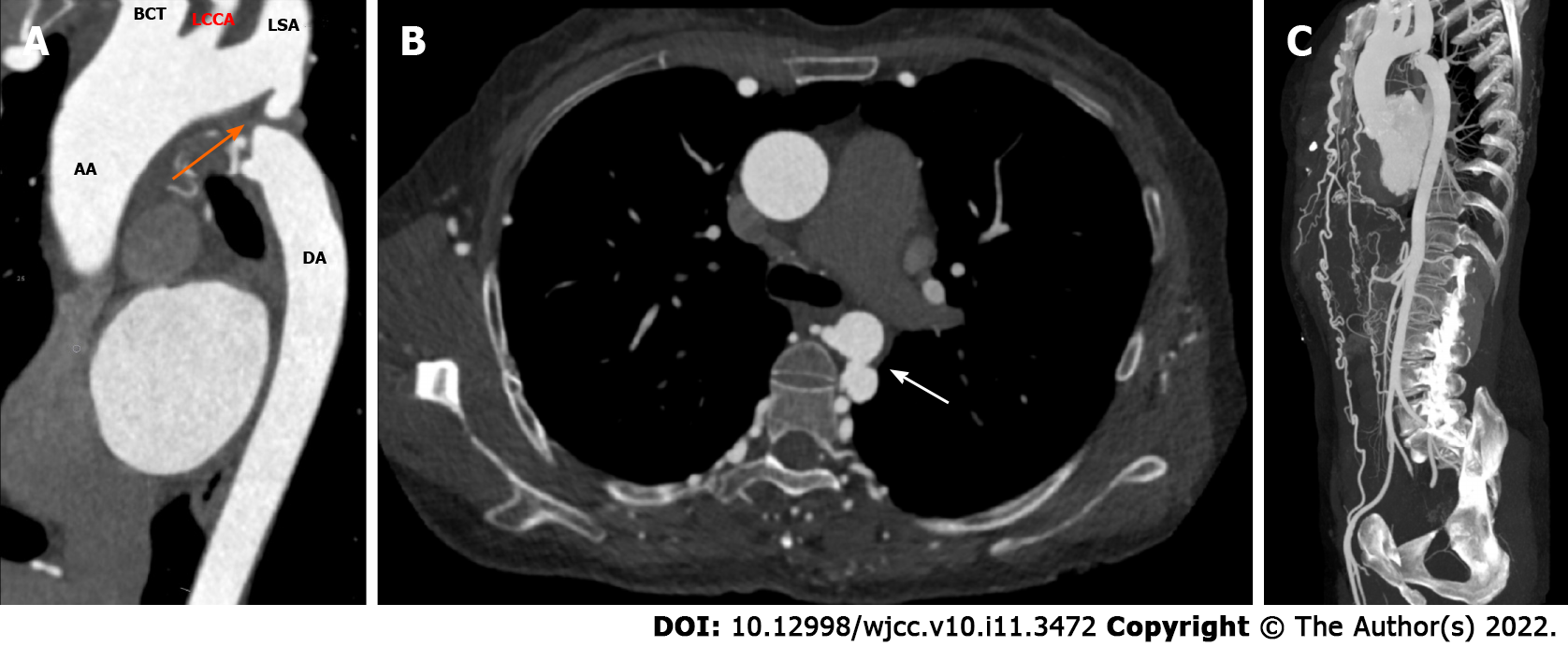

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) examination revealed multiple tortuous vascular shadows in the paravertebral column and bilateral chest wall areas. To further clarify the diagnosis, thoracic and abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed, which showed that the aortic arch and descending aorta were discontinuous, and the disconnection was located at the distal to the left subclavian artery (type A IAA) (Figure 1A). The ascending aorta was dilated with normal curvature and aneurysm formation in the descending aorta (Figure 1A and B). Bilateral internal mammary arteries, intercostal arteries, thoracoabdominal wall arteries, and multiple arterial branches tortuously expanded to supply blood to distal vessels and organs. For example, the bilateral internal mammary arteries were connected to the external iliac arteries (Figure 1C), and the blood of the abdominal trunk came from the intercostal artery and the inferior phrenic artery.

Case 2: ECG showed first degree atrioventricular block and abnormal Q wave in V1-V3 leads. Color Doppler echocardiography indicated no obvious enlargement in the atria or ventricles of the heart.

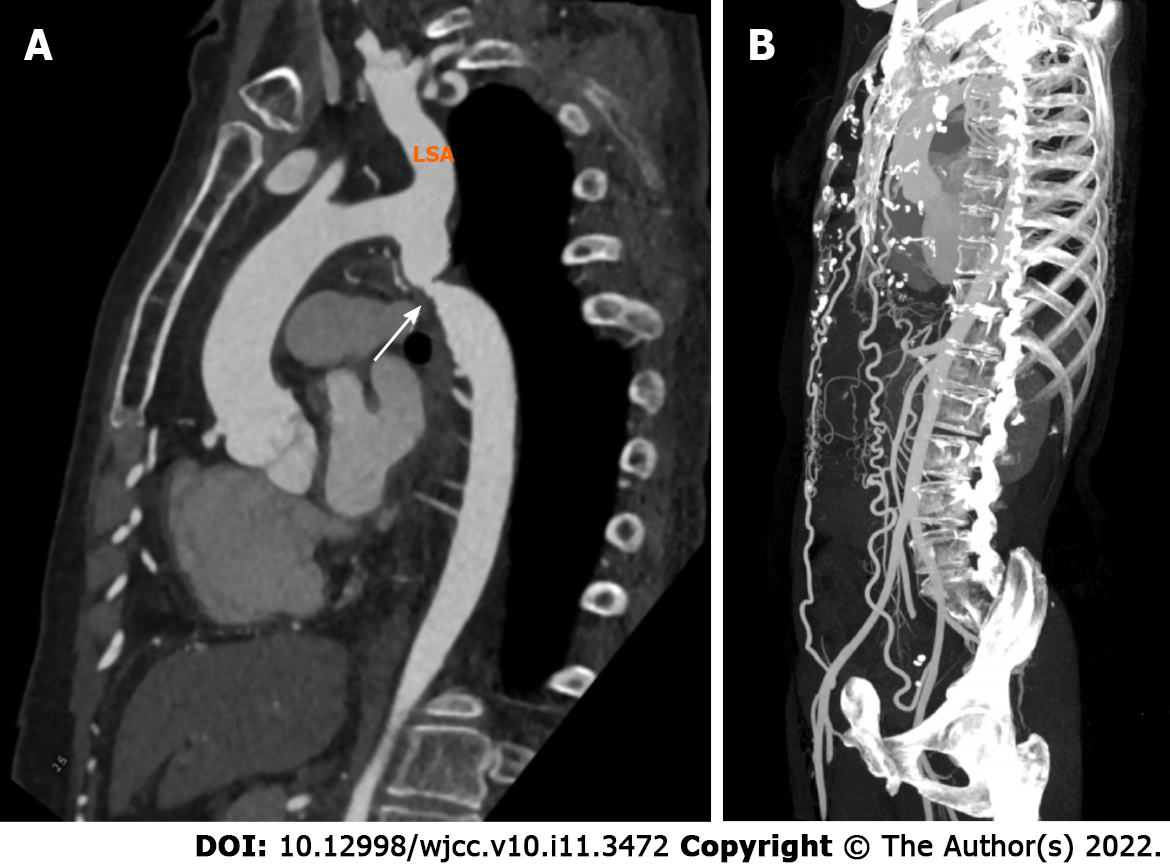

CTA examination showed that the lumen of the aortic isthmus was significantly narrowed (Figure 2A), the normal curvature of the ascending aorta was maintained, and the proximal descending aorta was slightly enlarged (Figure 2A). The bilateral internal mammary arteries were connected with the distal external iliac arteries (Figure 2B).

The maximum systolic pressure was acceptably controlled in the past with valsartan, hydrochlorothiazide tablets, and levamlodipine besylate tablets in Case 1. Oral administration of nifedipine controlled-release tablets (Bai Xintong), candesartan cilexetil, and indapamide sustained release tablets did not control blood pressure well in Case 2.

Based on the images of Figure 1 and 2, we diagnosed the two patients as having type A IAA and CoA with extensive collateral flow, respectively.

Without other positive symptoms, the first patient only required treatment of the relevant symptoms. The blood pressure controlled with antihypertensive drugs was acceptable during the follow-up period.

Due to uncontrollable hypertension, the second patient was admitted to the hospital and received aortic angiography and stent implantation under general anesthesia. The angiography indicated severe narrowing of the descending aorta 15 mm distal to the left subclavian artery, with a length of 10 mm. Before stent placement, the blood pressure at both ends of the constriction was 185/73 mmHg and 110/65 mmHg, respectively. After stent placement, the blood flow recovered smoothly, and the blood pressure at both ends of the stent was 127/62 mmHg and 122/62 mmHg, respectively.

Both of the patients have remained stable.

The difference between type A IAA and CoA in adults is the absence or presence of continuity of the arterial lumen. As shown in Case 1, there was no anatomical continuity between the distal to the left subclavian artery and descending aorta (type A IAA). In contrast, no obvious anatomical interruption was detected in CoA case with the narrowing between the above-mentioned arteries. According to previous reports, although the definitions of type A IAA and CoA were different, the clinical manifestations were similar in increased blood pressure, which was higher in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs[7-12]. The manifestations of Cases 1 and 2 in this study were consistent with these reports. The pathophysiological changes are: (1) Imbalanced distribution of blood flow and blood pressure in the upper and lower limbs is caused by increased mechanical resistance resulting from interruption or stenosis of the arterial lumen; and (2) hypoperfusion in lower bodies results in the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system[12]. Typical symptoms were not observed in the lower extremities of the two cases due to the fact that extensive collateral circulation was established to supply blood flow to the distal organs in both cases. As aggravation of the narrowing, upper limb blood pressure can be significantly increased, which may cause a series of symptoms such as upper limb pain, headache, dizziness, angina, and lower limb chills and claudication.

The mechanism of IAA in adults is different from that in infancy[1]. The most common type in infancy is the type B IAA which is closely related to congenital developmental abnormalities and may be concurrent with other anomalies including patent ductus arteriosus, aneurysm, ventricular septal defect, etc.[1,9]. While type A IAA in adults is similar to CoA in diseased anatomical position which is located between the left subclavian artery and the ductus arteriosus[13], type A IAA in adults may be the result of regression or atrophy of the diseased arterial segment as this segment can be narrowed, atretic, fibrotic, or completely absent[2]. Some researchers[9,13] believed that in CoA, the ascending aorta maintained normal curvature, the narrowing was located several centimeters away from the left subclavian artery, and distal to the coarctation was enlarged or formed aneurysm because increased velocity of blood flow at the region damaged the vessel wall[6,14]. These findings were seen in Case 1, which strongly suggested that adult type A IAA is the final stage of aortic coarctation degeneration. The IAA cases caused by severe CoA have also been reported in the literature[15,16]. The patients initially showed aorta narrowing. Over time, the complete obstruction of the narrowed lumens led to aortic interruption, which was eventually treated by surgical intervention.

The blood pressure of the patient with type A IAA in Case 1 could be controlled with drugs, so surgical intervention was not performed. Generally, the main treatment for IAA is to reconstruct the blood flow at both ends of the interrupted arteries, which can be achieved by surgical means (such as end-to-end anastomosis, graft interposition, or extra-anastomotic bypass) and percutaneous approach[1]. At present, there is still a lack of long-term follow-up data on adult patients with type A IAA repaired, and postoperative complications in these patients require continuous attention. The goal of surgery in CoA is the same as that in type A IAA, which is to reestablish the lesion to enable appropriate blood flow. Surgical methods for the treatment of CoA are mainly balloon angioplasty and stent placement[17]. The patient with severe CoA in Case 2 was treated by stent placement because of uncontrollable hypertension. Blood pressure at both ends of the stenosis returned to normal after surgery, and long-term follow-up observation will be essential for a series of complications after CoA is repaired, such as restenosis, hypertension, coronary artery disease, aortic rupture, and aneurysm formation[3,11,17].

Adult type A IAA and CoA have difference and similarity. The difference lies in the absence or presence of continuity of the arterial lumen, while the similarity is that they are accompanied by secondary hypertension with extensive collateral circulation. In conclusion, type A IAA is associated with CoA to a certain extent, and it can be considered that the arterial lumen is completely interrupted between the aortic arch and descending aorta with the degeneration or atrophy of arterial narrowing.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wierzbicka A, Poland S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Pérez TM, García SM, Velasco ML, Sánchez AP. Interrupted aortic arch diagnosis by computed tomography angiography and 3-D reconstruction: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | CELORIA GC, PATTON RB. Congenital absence of the aortic arch. Am Heart J. 1959;58:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 357] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | John AS, Schaff HV, Drew T, Warnes CA, Ammash N. Adult presentation of interrupted aortic arch: case presentation and a review of the medical literature. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6:269-275. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Vaideeswar P, Marathe S, Singaravel S, Anderson RH. Discontinuity of the arch beyond the origin of the left subclavian artery in an adult: Interruption or coarctation? Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2018;11:92-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Borgohain S, Gupta A, Grover V, Gupta VK. Isolated interrupted aortic arch in an 18-year-old man. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:79-81. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Franconeri A, Ballati F, Pin M, Carone L, Danesino GM, Valentini A. Interrupted aortic arch: A case report. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2020;30:81-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xiang XR, Chen ZX, Zhang L, Lei JQ, Guo SL. Interrupted aortic arch with multiple vascular malformations. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132:2386-2387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rencuzogullari I, Ozcan IT, Cirit A, Ayhan S. Isolated interrupted aortic arch in adulthood: A case report. Herz. 2015;40:549-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patel DM, Maldjian PD, Lovoulos C. Interrupted aortic arch with post-interruption aneurysm and bicuspid aortic valve in an adult: a case report and literature review. Radiol Case Rep. 2015;10:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhou JM, Liu XW, Yang Y, Wang BZ, Wang JA. Secondary hypertension due to isolated interrupted aortic arch in a 45-year-old person: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Canniffe C, Ou P, Walsh K, Bonnet D, Celermajer D. Hypertension after repair of aortic coarctation--a systematic review. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2456-2461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Agasthi P, Pujari SH, Tseng A, Graziano JN, Marcotte F, Majdalany D, Mookadam F, Hagler DJ, Arsanjani R. Management of adults with coarctation of aorta. World J Cardiol. 2020;12:167-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 13. | Vriend JW, Lam J, Mulder BJ. Complete aortic arch obstruction: interruption or aortic coarctation? Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2004;20:393-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Skandalakis JE, Edwards BF, Gray SW, Davis BM, Hopkins WA. Coarctation of the aorta with aneurysm. Int Abstr Surg. 1960;111:307-326. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kaneda T, Miyake S, Kudo T, Ogawa T, Inoue T, Matsumoto T, Onoe M, Nakamoto S, Kitayama H, Saga T. Obstructed coarctation in a right aortic arch in an adult female. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51:350-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hudsmith LE, Thorne SA, Clift PF, de Giovanni J. Acquired thoracic aortic interruption: percutaneous repair using graft stents. Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hu ZP, Wang ZW, Dai XF, Zhan BT, Ren W, Li LC, Zhang H, Ren ZL. Outcomes of surgical vs balloon angioplasty treatment for native coarctation of the aorta: a meta-analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:394-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |