Published online Jan 15, 2019. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v11.i1.59

Peer-review started: July 17, 2018

First decision: August 8, 2018

Revised: September 13, 2018

Accepted: October 12, 2018

Article in press: October 12, 2018

Published online: January 15, 2019

Processing time: 183 Days and 10.5 Hours

To present a comprehensive review of the etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of Gut-associated lymphoid tissue or “dome” carcinoma of the colon.

The English language medical literature on gut- or gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) or “dome” carcinoma of the colon was searched and appraised.

GALT/dome-type carcinomas of the colon are thought to arise from the M-cells of the lymphoglandular complex of the intestine. They are typically asymptomatic and have a characteristic endoscopic plaque- or “dome”-like appearance. Although the histology of GALT/dome-type carcinomas displays some variability, they are characterized by submucosal localization, a prominent lymphoid infiltrate with germinal center formation, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, absence of desmoplasia, and dilated glands lined by columnar epithelial cells with bland nuclear features and cytoplasmic eosinophilia. None of the patients reported in the literature with follow-up have developed metastatic disease or local recurrence.

Increased awareness amongst histopathologists of this variant of colorectal adenocarcinoma is likely to lead to the recognition of more cases.

Core tip: This review comprehensively presents the etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of gut- or gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) or “dome” carcinoma of the colon. These lesions are thought to arise from the M-cells of the GALT (lymphoglandular complex) of the intestine. They have a characteristic endoscopic plaque- or “dome”-like appearance. Histologically, they are characterized by submucosal localization, a prominent lymphoid infiltrate with germinal center formation, and dilated glands lined by bland columnar epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. There have been no reports of metastatic disease or local recurrence in patients with colonic GALT/dome-type carcinomas.

- Citation: McCarthy AJ, Chetty R. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue or so-called “dome” carcinoma of the colon: Review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2019; 11(1): 59-70

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5204/full/v11/i1/59.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4251/wjgo.v11.i1.59

Carcinomas that are accompanied by a lymphoid component are a well-recognized entity in several topographic sites. The prototype is the Epstein Barr virus (EBV)-driven nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In the gastrointestinal tract, there are distinct pathogenetic types of cancers that are associated with significant lymphoid infiltrates. The vast majority are either associated with microsatellite instability: inherited [Lynch syndrome (LS)] or as a sporadic hypermethylation event (usually of MLH-1); or secondly, EBV-associated lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. There remains a third form of gastrointestinal cancer that is strongly associated with lymphoid tissue, the so-called dome or gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) carcinoma. This is a rare, enigmatic form of gastrointestinal cancer and the subject of this review. Our aim is to present a comprehensive review of the etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of this entity.

The English language medical literature on GALT or “dome” carcinoma of the colon was searched and appraised, using recognized search engines, PubMed and Google, with the keywords: “gut-associated lymphoid tissue”; “gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue”; “GALT carcinoma”; “dome carcinoma”; “colon”.

Cases of GALT or “dome” carcinoma of the colon have been reported as single case reports and as small case series in the English language medical literature (Table 1). The remainder of this paper discusses the pertinent features of this entity, as garnered from the literature search.

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Gender | Symptoms | Associations | Site | Size (mm) |

| De Petris et al[15] | 44 | M | Pain, loss of weight | Lynch syndrome | Ileocecal valve | 9 |

| Jass et al[4] | 56 | M | Asymptomatic | FAP/CRC | Ileocecal valve | 30 |

| Clouston et al[25] | 63 | F | NS | NS | Sigmoid colon | NS |

| Clouston et al[25] | 56 | M | NS | NS | Sigmoid colon | 14 |

| Rubio et al[3] | 53 | F | Diarrhea | UC | Ascending colon | NS |

| Stewart et al[26] | 70 | M | Asymptomatic | UC | Ascending colon | 5 |

| Stewart et al[26] | 63 | F | Diverticular disease | NR | Transverse colon | 17 |

| Asmussen et al[24] | 76 | F | Rectal bleeding | NR | Sigmoid colon | 20 |

| Asmussen et al[24] | 36 | F | Rectal bleeding | NR | Rectum | 24 |

| Rubio et al[2] | 53 | F | Asymptomatic | FH CRC | Ascending colon | 8 |

| Coyne[27] | 76 | M | Asymptomatic | FH CRC | Cecum | 23 |

| Puppa et al[18] | 56 | M | Painful constipation | ALS | Right hepatic flexure | 8 |

| Yamada et al[59] | 77 | M | Abdominal discomfort | NS | Transverse colon | 30 |

| Rubio et al[16] | 68 | F | Surveillance colonoscopy | UC; breast cancer | Transverse colon | NS |

| Yamada et al[19] | 76 | F | NS | NS | Rectum | 10 |

| Zhou et al[46] | 47 | M | Rectal bleeding | CRC | Proximal descending colon | 8 |

| Kannuna et al[1] | 57 | F | Abdominal pain | NR | Cecum | 30 |

The mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in the intestine is also termed gastrointestinal or GALT and is also occasionally referred to as lymphoglandular complexes[1]. The colorectal mucosa is divided into two quantitatively, structurally and functionally dissimilar elements[2]. The first element comprises the vast majority of colorectal mucosa and is not associated with lymphoid tissues (“GALT-free mucosal area”). This is composed of mucus-producing goblet cells and absorptive columnar cells with regular, closely packed microvilli roofed by glycocalyx, which is a thick extra-cellular glycoprotein layer[3]. The function of this large GALT-free mucosal area is to protect underlying structures and to actively absorb fluids, vitamins and other nutrients[2].

The second component of the colorectal mucosa is GALT. This is characterized by discrete lymphoid aggregates, which are scattered throughout the small and large intestine. Larger components of GALT are present in the terminal ileum (termed “Peyer’s patches”) and in the anorectal region[4]. The GALT nodules comprise lymphoid follicles, which are composed of B-lymphocytes. Following antigenic stimulation, these follicles develop into a germinal center surrounded by a mantle zone. Within the GALT nodules, there are also inter-follicular areas that contain T-lymphocytes[4].

A follicle-associated epithelium overlies the lymphoid follicles. This is composed of a single layer of enterocytes and specialized epithelial columnar cells (microfold, glycocalyx-free “M-cells”); this epithelial layer is devoid of goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells[3,5]. M-cells differ from absorptive cells by having a less well-developed apical membrane, as opposed to regular microvilli. M-cells also lack lysosomes, but rather contain numerous transport vesicles, their principal function being to translocate antigens and pathogens from the gut lumen to the underlying lymphoid population[6].

The surface epithelium overlying GALT normally contains intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), including both T- and B- lymphocytes. The remainder of the intestinal epithelium shows intraepithelial T-lymphocytes only[7]. Both B- and T-lymphocytes are capable of invaginating into the basolateral membranes of M-cells. In doing so, intra-cellular pockets with a relatively thin overlying rim of cytoplasm are produced. In turn, the lymphocytes are brought into close contact with pinocytotic vesicles containing antigenic material[6,7].

Background: The first description of colonic glands surrounded by lymphoid stroma located in the submucosa was in 1954 when Dukes[8] described lesions in colitic patients, characterized by “misplaced” colonic epithelium surrounded by nodular lymphoid tissue. It was postulated that this misplaced epithelium was the result of mucosal repair following ulceration, and that the epithelium, which had detached and was buried in the submucosa, encouraged cancer development[8,9]. It was later demonstrated however, that the misplacement was in fact a mucosal herniation into the submucosa[10].

In 1981, Oohara et al[11] reported that 55% of microscopic adenomas in large bowel resection specimens from patients with colonic carcinoma originated from epithelial cells overlying colonic lymphoid follicles. The authors postulated that colonic lymphoid follicles can be associated with early neoplasms (adenomas or adenocarcinomas)[11]. This association may only be demonstrable however in very small and/or early tumors, since lymphoid patches are rapidly invaded and destroyed by the tumor[11]. Other studies have also supported the theory that aggregates of lymphoid tissue in the colon play a promotional role in adenocarcinoma formation[12,13].

In 1984, Rubio[14] investigated the presence of ectopic colonic mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease, defining “ectopic colonic mucosa” as misplaced colonic glands either in the muscularis mucosae, in the submucosa, or in the muscle layer[14]. Foci of ectopic colonic mucosa were present in 72% and 55% of UC and Crohn’s disease specimens, respectively. They found that the misplaced glands were often surrounded by lymphoid aggregates. Dysplasia in ectopic colonic mucosa was significantly more frequent in UC than in Crohn’s disease[14].

Original descriptions: In 1984, carcinoma of the colon originating in lymphoid-associated mucosa in a patient with UC was first documented and was coined “GALT carcinoma”[14]. Subsequently, the term “dome-type carcinoma” was first used in 1999 by De Petris et al[15] when describing the macroscopic appearance of a dome-shaped elevation of the mucosa in a colonic carcinoma associated with GALT.

As described by De Petris et al[15], dome-type carcinomas have a constellation of characteristic features, namely an endoscopic elevated, dome-like appearance and microscopically dilated, malignant/dysplastic glands lined by columnar epithelium with eosinophilic cytoplasm, with a background of prominent lymphoid tissue[15]. In the past, dome-type carcinomas have been distinguished from GALT carcinomas by the presence of cystically dilated glands lined by eosinophilic columnar epithelium. However, these cyto-architectural features have also been described in GALT carcinoma[3]. Both show a plaque-like/sessile macroscopic appearance, are typically limited to the submucosa, are intimately associated with GALT, and are well-differentiated low-grade lesions. Thus, it has been suggested by several authors that dome-type carcinoma and GALT carcinoma should be considered as slight variants of the same entity[1]. As such, the umbrella term “GALT/dome-type carcinoma” is used throughout the remainder of this review and GALT carcinoma and dome-type carcinoma are regarded by the authors as synonymous.

Clinical features: The exact incidence of GALT/dome-type carcinoma is not known, as it has been reported as single case reports and as small case series in the English language medical literature. The clinical features of these cases are outlined in Table 1.

Most cases of GALT/dome-type carcinoma are detected incidentally and are reported either as sporadic-type colon cancer or in association with UC[16,17], familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)[15], LS[2] and other positive family histories of colorectal cancer (CRC), although it is thought that GALT/dome-type carcinoma is not associated with any specific mechanisms of tumor predisposition[18]. GALT/dome-type carcinomas have been identified in both the right and left colon. They have been described in both genders with almost equal frequency and in patients with a relatively wide age range (36 to 77 years). The size of GALT/dome-type carcinoma ranges from 5 mm to 30 mm (mean: 16.85 mm, Table 1).

Gross appearance: Most GALT/dome-type carcinomas have a plaque-like, sessile, slightly polypoid appearance. Due to their expansive growth pattern, they appear to represent a submucosal lesion endoscopically[15,19].

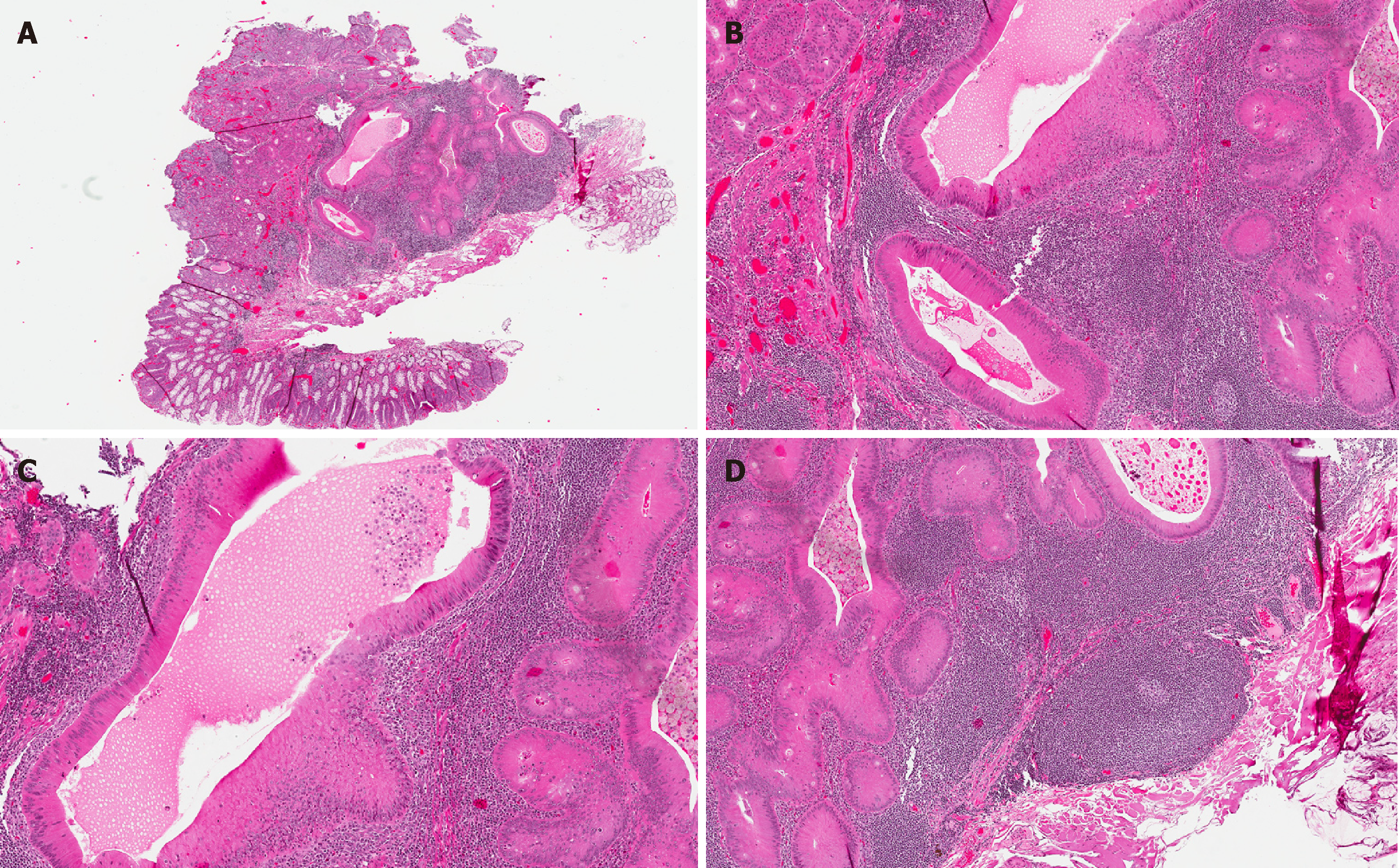

Histological features and immunohistochemical and ancillary findings: The vast majority of GALT/dome-type carcinomas are well-circumscribed and confined to the submucosa of the bowel wall (Figure 1A). These lesions are characterized by a constellation of distinctive features, namely glands lined by eosinophilic epithelial cells, admixed with lymphoid stroma, including germinal center formation.

The glands are typically lined by well-differentiated, eosinophilic columnar epithelial cells (reminiscent of oncocytes) (Figure 1B). Goblet cells are invariably absent, and this can be confirmed immunohistochemically by the complete absence of MUC2 expression[4]. Most glands are cystically dilated and contain an abundance of necrotic to eosinophilic debris in their lumina (Figure 1C). This secretory luminal material is periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) diastase (PAS-D) positive, and it also stains for MUC1, which is expressed by columnar cells[20].

The lymphoid stroma comprises well-formed lymphoid follicles with germinal centers (Figure 1D). It is thought that the stromal lymphoid component associated with these tumors represents remnants of pre-existing resident organized lymphoid nodules of the colorectal mucosa, rather than a reactive immune response, as has been shown for other neoplasms of the gut and of extra-intestinal origin[21-23]. Rare cases of GALT/dome-type carcinomas have shown patchy threadbare associated lymphoid tissue[24], and this has resulted in the suggestion that advanced examples of GALT/dome-type carcinomas may lead to effacement of the accompanying lymphoid component[4].

Most cases of GALT/dome-type carcinoma show IELs within the glands; mainly B-lymphocytes, but T-lymphocytes have also been noted. However, IELs may be absent in some cases (Figure 1B)[24].

A pre-existing associated adenoma has been described in almost half of GALT/dome-type carcinoma cases. In those cases lacking an overlying adenomatous component, it has been suggested that some of these tumors may have arisen from submucosal follicle-associated epithelium or from herniated colonic glands into the submucosa, as typically noted in UC[14,16].

Usual type or conventional colorectal adenocarcinoma has also been observed coexisting within some GALT/dome-type carcinomas[1,25]. The relative rarity of GALT/dome-type carcinomas as an entity could be explained by the theory that the GALT/dome-type carcinoma component is obliterated by overgrowth of the usual conventional carcinoma[1,25].

Jass et al[4] confirmed the presence of a well-developed brush border in GALT/dome-type carcinoma ultrastructurally. All GALT/dome-type carcinomas that have been tested are DNA microsatellite stable, either by mismatch repair immunohistochemistry or by microsatellite instability testing. In-situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small RNA-1 (EBER) was negative in cases tested, indicating that the GALT/dome-type carcinoma is unrelated to EBV infection[19].

Why are GALT/dome-type carcinomas so rare? GALT/dome-type carcinomas are extremely rare, and the reason for this apparent rarity is a matter of conjecture. Under-diagnosis from lack of recognition of the characteristic endoscopic and pathological features, or effacement of these typical features as a result of tumor progression, have been postulated[4,24-26]. Several cases have adjacent foci of usual-type colorectal adenocarcinoma, perhaps supporting the contention that GALT/dome-type carcinomas are effaced by conventional colorectal adenocarcinoma, hence their rarity[15,24,25,27].

Do GALT/dome-type carcinomas actually exist? The intimate admixture of lymphoid aggregates and columnar epithelial glands of these lesions resembles GALT or lymphoglandular complexes[28,29]. As mentioned previously, GALT is a normal structural component of the large bowel occurring close to the muscularis mucosae, located either above it in the lamina propria or below it in the submucosa. De Petris et al[15] speculated that GALT/dome-type carcinoma is the malignant counterpart of GALT and that it may in fact represent a precursor of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma because of the tumor-associated lymphoid stroma. There are several lines of evidence (outlined below) establishing a connection between GALT and GALT/dome-type carcinoma, supporting the concept that this tumor may originate from M-cells of follicle associated epithelium, and does indeed represent a distinctive entity: (1) Intra-epithelial B-lymphocytes: GALT/dome-type carcinomas demonstrate foci of intra-epithelial B-lymphocytes within the lesional epithelium. Intra-epithelial B-lymphocytes are normally encountered only within the M-cells of gut epithelium[7], and this has been cited as supporting evidence for the origin of GALT/dome-type carcinomas. However, it has not been possible to provide further proof of the presence of M-cells within GALT/dome-type carcinomas, due to the poor preservation at the electron microscopic level and the lack of specific M-cell markers[4]. Also, rare cases of GALT/dome-type carcinoma can also display a complete absence of IELs[24]; and (2) Absence of goblet cells: Additional corroborating evidence for M-cell epithelial differentiation is derived from the fact that the columnar epithelium of GALT/dome-type carcinomas is highly differentiated with a well-developed brush border, and lacks goblet cells and the specific goblet cell mucin MUC2[4]. This profile mimics the normal follicle-associated epithelium of GALT, which is composed of a single cell layer of M-cells and is devoid of goblet cells and endocrine cells.

There are several lines of evidence on the putative etiology:

Rat experimental models: Dimethylhydrazine (DMH) has been shown to induce intestinal adenocarcinoma in rats, which is regularly associated with Peyer’s patches, coined “lymphoid-patch-associated carcinomas”[30,31]. Martin et al[31] studied early lymphoid-tissue-associated carcinomas and found that these lesions were located in the submucosa and in the para- or inter-follicular areas of Peyer’s patches, and they were thought to originate from the epithelium covering the lymphoid follicles. They also found misplaced, often atypical, glandular structures in the para- or inter-follicular areas of lymphoid patches in control rats[32,33]. These atypical glands were located in the same area as that of the lymphoid-patch-associated carcinomas in DMH-treated animals. This led the authors to suggest that a relationship exists between these particular cancers and the crypts trapped in lymphoid patches[31].

GALT in UC: O’Leary and colleagues found 36 GALT foci per colectomy specimen in patients without UC, and up to 168 GALT foci per colectomy in UC patients; i.e., GALT foci are 4.7 times more frequent in the colons of patients with UC than in those without[28]. The authors concluded that in the colon of patients with UC, new GALTs are formed, presumably as part of the inflammatory process. It is therefore not inconceivable that the GALT/dome-type carcinomas reported in patients with UC might have evolved in a newly formed, UC-dependent, GALT complex[16]. This theory is supported by the finding of a relatively frequent occurrence of UC in patients with GALT/dome-type carcinoma.

Relationship to overlying adenoma: It is reasonable to postulate that cases diagnosed as GALT/dome-type carcinoma that had an overlying advanced adenoma actually resulted from direct extension of the adenoma into the underlying GALT or from evolution of the adenoma into an adenocarcinoma, which then directly invaded into the underlying GALT. However, in some GALT/dome-type carcinomas, serial sections did not show continuity between the adenomas and the GALT/dome-type carcinomas, nor invasive growth in the adenoma[16].

Cancer arising in a pre-existing lymphoid polyp: It has been debated whether GALT/dome-type carcinomas could be interpreted as representing cancers arising in a pre-existing lymphoid polyp[4]. However, this theory is considered unlikely, as solitary lymphoid polyps are extremely rare in the large bowel, and when they do occur, they are typically limited to the ano-rectal region[32].

Analogy to Warthin’s tumors: GALT/dome-type carcinomas are reminiscent of Warthin’s tumors of salivary glands in which the epithelial component has a distinctive oncocytic, papillary-cystic appearance and is associated with a lymphoid component, often replete with germinal centers[33]. The etiology of Warthin’s tumor is controversial, but the most widely accepted theory is that it represents a neoplastic proliferation of heterotopic salivary gland ducts within intra- or para-parotid lymph nodes[34]. However, other authors have suggested that it is an adenoma with lymphocytic infiltration[35,36].

Allegra proposed hypersensitivity as the main cause of histogenesis of Warthin’s tumor, with oxyphilic metaplasia of striated ducts being followed by papillary formations with secretion, leading to cyst formation[37]. Basophils and histiocytes then infiltrate the basement membrane, resulting in a delayed hypersensitivity reaction and formation of lymphoid stroma[38,39].

Classical cytogenetics studies have identified clonal abnormalities in some Warthin tumors[40-42], while other studies have concluded that they are non-neoplastic[33,43]. Whether they are true neoplasms arising as clonal proliferations or developmental malformations with a non-neoplastic origin remains to be elucidated[44,45].

Analogous to Warthin’s tumors, perhaps GALT/dome-type carcinomas represent a neoplastic proliferation of lymphoglandular complexes, or represent lymphocytic infiltration of heterotopic dysplastic glands. To the best of our knowledge, cytogenetics studies of GALT/dome-type carcinomas have not been performed and may prove to be informative.

GALT/dome-type carcinomas and conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas have distinctive origins: the former originate in GALT, while conventional CRCs arise from GALT-free mucosa.

Given that the appellation “carcinoma” is in the term “GALT/dome-type carcinoma”, it seems implicit that these lesions are malignant or at least have malignant potential. However, unlike conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas, almost all GALT/dome-type carcinomas are limited to the submucosa, and recurrences and metastases to lymph nodes or to distant sites have not been documented.

Given the distinctive histological features, low disease stage, good behavior and lack of consensus regarding the exact etiology and clinical significance, it seems prudent to separate GALT/dome-type carcinomas from conventional colorectal adenocarcinomas.

A range of both benign and malignant differential diagnoses should be considered prior to rendering a diagnosis of GALT/dome-type carcinoma:

Colitis cystica profunda is a rare benign condition characterized by misplacement of cystically dilated, mature crypts through the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa[46]. The crypts are typically lined by bland epithelial cells surrounded by normal lamina propria, and may contain eosinophilic luminal material[47]. Hemosiderin and foreign body type giant cells can also be seen adjacent to these crypts, and step-wise sections may show a connection to the surface epithelium. Colitis cystica profunda is associated with mucosal prolapse, severe infection, ischemia and inflammatory bowel disease, and may occur in irradiated bowels and along surgical anastomotic lines. Mechanisms of misplacement include herniation, implantation after ulceration, mucosal micro-diverticula, and re-epithelialization of fistulae (in Crohn’s disease for example)[47]. Similar to GALT/dome-type carcinoma, localized colitis cystica profunda presents as a rectal nodule or plaque associated with mucosal prolapse/solitary rectal ulcer syndrome[48].

Inverted hyperplastic polyp is also termed “hyperplastic polyp with epithelial misplacement” and is an unusual morphological variant of a hyperplastic polyp characterized by misplacement of crypt epithelium into the underlying submucosa[49]. It is thought that misplacement of epithelium occurs secondary to torsion or twisting of the polyp leading to protrusion of glands through inherently weak regions of the muscularis mucosae, such as those that occur normally adjacent to lymphoid aggregates[28].

Inverted hyperplastic polyps are characterized by submucosally-located well-delineated lobules of misplaced epithelium and/or irregular congeries of crypts that are morphologically similar to that seen in the lower third of the overlying hyperplastic polyp[49]. Evidence of local trauma with hemosiderin deposition, fresh hemorrhage and submucosal vascular congestion are present[49]. Although these lesions typically lack lymphoid aggregates, they can be present adjacent to foci of misplaced epithelium in approximately one-third of cases[49].

Polypoid colonic hamartomatous inverted polyp is a benign lesion of the rectum, due to an inverted or downward growth of mucosal glands through the muscularis mucosa into the submucosa[46]. Microscopically, a circumscribed group of ectopic distorted, slightly atypical mucus glands are present in the submucosa, pushing the mucosa up to form a polypoid mass[50]. Epithelial eosinophilia and lymphoid aggregates are not a feature of this lesion. It is now thought that cases reported as “polypoid colonic hamartomatous inverted polyp” represent colitis cystica profunda.

Inverted colonic mucosal lesion has been reported in a published case report[51]. Grossly, this was a depressed lesion, and histologically, the inverted glands present in the submucosa were morphologically similar to the overlying normal colonic mucosal glands.

Endometriosis of the colon can mimic GALT/dome-type carcinoma at low power. In the absence of obvious endometrial stroma, CD10 immunohistochemistry can be performed[52].

Adenoma with pseudoinvasion/epithelial misplacement is most frequently seen in large pedunculated polyps from the left colon, usually the sigmoid colon[53]. It is usually due to repeated twisting and torsion of the polyp causing vascular compromise, ischemic injury, hemorrhage, and herniation of the epithelium through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa[53,54]. In pseudoinvasion, the misplaced epithelium in the submucosa usually has a rounded, lobular configuration and exhibits either low- or high-grade dysplasia, typically similar to the intra-mucosal portion of the polyp. These misplaced glands are surrounded by a rim of lamina propria, with hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition, as well[54,55]. There may also be mucin pools within the submucosa[53], and these tend to be smooth, regular, and associated with ruptured crypts. They can be either acellular or lined by dysplastic epithelium similar to that seen at the surface of the polyp[53]. Lamina propria does not surround the glands of GALT/dome-type carcinomas, and mucin pools, hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition are not typical features.

Colorectal adenocarcinoma can be associated with a dense lymphoid component, such as medullary-like carcinoma and CRC occurring in the context of LS and sporadic microsatellite instability-high (MSIH) CRC[56]. (1) MSI-H CRC: Lymphocytic infiltration in MSI-H CRC can be as peri-tumoral nodular lymphoid aggregates or as tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)[56]. TILs in MSI-H CRC are CD8-positive T-cells[57]. In contrast, the TILs in GALT/dome-type carcinomas are mainly B- lymphocytes[4]. These MSI-H CRCs are usually mucin-producing poorly differentiated tumors[56], unlike the well-formed glands seen in GALT/dome-type carcinoma; (2) Medullary-like carcinoma is a subtype of microsatellite unstable CRC[23]. At least 90% of the tumor has a solid and syncytial architectural pattern (sheets, nests or trabeculae), with a pushing or expansile margin. The tumor cells are medium-sized, with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli with a pattern of growth[58]. A striking peri- and intra-tumoral lymphoid infiltrate is typical[15,23]. Dilated cystic glands are not a feature.

Although most GALT/dome-type carcinomas are cytologically and architecturally malignant, it is thought that they represent early low-grade lesions limited to the submucosa (pT1). Exceptions were the cases reported by Asmussen et al[24] in 2008 (a pT2 lesion) and by Yamada et al[59] in 2012 (a pT3 lesion). Metastases to lymph nodes or distant sites have not been reported. Given that any type of lymphocytic infiltration in CRC is considered a good prognostic factor[60], it is perhaps not surprising that there are no reported recurrences or cancer-related deaths from GALT/dome-type carcinoma[1]. However, this may merely be reflective of the early, non-advanced nature of GALT/dome-type carcinoma cases described thus far[24].

All documented cases of GALT/dome-type carcinoma were diagnosed on polypectomy or large bowel resection specimens. There were no reports of additional surgery being performed or of adjuvant therapy (radiation and/or chemotherapy) being administered. Although numbers are small, recurrences or metastases have not been reported for any patients with GALT/dome-type carcinoma, and, thus it seems reasonable to conclude that adequate local excision is sufficient treatment.

Current classifications of gastrointestinal tract cancers do not recognize GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct histological subtype, although these lesions do demonstrate distinctive histological and clinical characteristics. A diagnosis of GALT/dome-type carcinoma should be considered when a well-circumscribed, submucosal lesion composed of cystic dilated glands containing eosinophilic material, lined by a single layer of non-mucinous, eosinophilic epithelium, accompanied by a conspicuous lymphoid component replete with germinal centers and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, is seen.

Accumulation of cases and phenotypic characterization, including the relationship to M-cells, may establish GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the future.

Carcinomas that are accompanied by a lymphoid component are a well- recognized entity in several topographic sites. In the gastrointestinal tract, dome or gut- or gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) carcinoma (GALT/dome-type carcinoma) is a rare, enigmatic form of gastrointestinal cancer. Current classifications of gastrointestinal tract cancers do not recognize GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct histological subtype, although these lesions do demonstrate distinctive histological and clinical characteristics. This is a comprehensive review of the etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of this entity. A diagnosis of GALT/dome-type carcinoma should be considered by pathologists when a well-circumscribed, submucosal lesion composed of cystic dilated glands containing eosinophilic material, lined by a single layer of non-mucinous, eosinophilic epithelium, accompanied a conspicuous lymphoid component replete with germinal centers and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, is seen.

Comprehensive clinical and pathological reviews of GALT/dome-type carcinoma are lacking. With this in mind, the key topics covered included the etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of GALT/dome-type carcinoma. The authors reviewed the published literature to provide evidence to address the following questions: Why are GALT/dome-type carcinomas so rare? Do GALT/dome-type carcinomas actually exist? What is the etiology of GALT/dome-type carcinomas? Are GALT/dome-type carcinomas a separate category distinct from conventional adenocarcinomas? There is considerable evidence summarized herein that supports the theory that GALT/dome-type carcinoma is a distinct histological subtype, as these lesions do demonstrate distinctive histological and clinical characteristics. Increased awareness of this entity amongst pathologists and clinicians will enable the correct diagnosis and thus facilitate the accumulation of cases and phenotypic characterization, which may establish GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the future.

The objective was to search and appraise the English language medical literature on GALT or “dome” carcinoma of the colon. The pertinent etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of GALT/dome-type carcinoma are presented herein. The authors provide evidence garnered from the literature to address the following pressing questions: Why are GALT/dome-type carcinomas so rare? Do GALT/dome-type carcinomas actually exist? What is the etiology of GALT/dome-type carcinomas? Are GALT/dome-type carcinomas a separate category distinct from conventional adenocarcinomas? It has been shown that GALT/dome-type carcinomas do demonstrate distinctive histological and clinical characteristics, and as such, should be considered a distinct histological subtype. Increased awareness of this entity amongst pathologists and clinicians will enable the correct diagnosis and thus facilitate the accumulation of cases and further characterization, which may confirm GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the future.

The English language medical literature on GALT or “dome” carcinoma of the colon was searched and appraised, using recognized search engines, PubMed and Google, with the keywords: “gut-associated lymphoid tissue”; “gastrointestinal-associated lymphoid tissue”; “GALT carcinoma”; “dome carcinoma”; “colon”. Cases of GALT or “dome” carcinoma of the colon have been reported as single case reports and as small case series in the English language medical literature. The relevant literature was thoroughly reviewed and appraised.

Based on the published literature, GALT/dome-type carcinomas do demonstrate distinctive etiological, histological and clinical characteristics. The number of published cases is small, however, and additional cases should be identified to enable further interrogation, which may provide even more robust evidence to firmly establish GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the future.

The pertinent etiology, clinical features, macroscopic and pathological findings, and clinical significance of GALT/dome-type carcinoma are presented herein. The published literature provides evidence that GALT/dome-type carcinomas do indeed demonstrate distinctive etiological, histological and clinical characteristics. Published evidence explaining the rarity and etiology of GALT/dome-type carcinomas is summarized. Published evidence supporting the concept that GALT/dome-type carcinomas actually exist is explored. Overall, the literature supports the designation of GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a separate category distinct from conventional adenocarcinomas. The key histological and clinical characteristics of GALT/dome-type carcinoma are emphasized to increase awareness amongst clinicians and pathologists. Additional cases should be identified to enable further interrogation, which may provide even more robust evidence to firmly establish GALT/dome-type carcinoma as a distinct subtype of colorectal adenocarcinoma in the future.

Evidence suggests that GALT/dome-type carcinoma is indeed a separate entity distinct from conventional adenocarcinoma. However, additional cases are required to enable further interrogation of larger numbers of cases to confirm this theory. Awareness amongst histopathologists of the diagnostic criteria to render a diagnosis is essential to facilitate the identification and collection of additional cases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Jeong KY, Ren K S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Kannuna H, Rubio CA, Silverio PC, Girardin M, Goossens N, Rubbia-Brandt L, Puppa G. DOME/GALT type adenocarcimoma of the colon: a case report, literature review and a unified phenotypic categorization. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rubio CA, Lindh C, Björk J, Törnblom H, Befrits R. Protruding and non-protruding colon carcinomas originating in gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3019-3022. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rubio CA, Talbot I. Lymphoid-associated neoplasia in herniated colonic mucosa. Histopathology. 2002;40:577-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jass JR, Constable L, Sutherland R, Winterford C, Walsh MD, Young J, Leggett BA. Adenocarcinoma of colon differentiating as dome epithelium of gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Histopathology. 2000;36:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhalla DK, Owen RL. Cell renewal and migration in lymphoid follicles of Peyer’s patches and cecum--an autoradiographic study in mice. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:232-242. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Neutra MR. Current concepts in mucosal immunity. V Role of M cells in transepithelial transport of antigens and pathogens to the mucosal immune system. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G785-G791. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gebert A, Rothkötter HJ, Pabst R. M cells in Peyer’s patches of the intestine. Int Rev Cytol. 1996;167:91-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dukes CE. The surgical pathology of ulcerative colitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1954;14:389-400. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hultén L, Kewenter J, Ahrén C. Precancer and carcinoma in chronic ulcerative colitis. A histopathological and clinical investigation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1972;7:663-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dyson JL. Herniation of mucosal epithelium into the submucosa in chronic ulcerative colitis. J Clin Pathol. 1975;28:189-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Oohara T, Ogino A, Tohma H. Microscopic adenoma in nonpolyposis coli: incidence and relation to basal cells and lymphoid follicles. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:120-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cameron IL, Garza J, Hardman WE. Distribution of lymphoid nodules, aberrant crypt foci and tumours in the colon of carcinogen-treated rats. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:893-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hardman WE, Cameron IL. Colonic crypts located over lymphoid nodules of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-treated rats are hyperplastic and at high risk of forming adenocarcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:2353-2361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rubio CA. Ectopic colonic mucosa in ulcerative colitis and in Crohn’s disease of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1984;27:182-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De Petris G, Lev R, Quirk DM, Ferbend PR, Butmarc JR, Elenitoba-Johnson K. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the colon in a patient with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:720-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rubio CA, Befrits R, Ericsson J. Carcinoma in gut-associated lymphoid tissue in ulcerative colitis: Case report and review of literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rubio CA, DE Petris G, Puppa G. Gut-associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) Carcinoma in Ulcerative Colitis. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:919-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Puppa G, Molaro M. Dome-type: a distinctive variant of colonic adenocarcinoma. Case Rep Pathol. 2012;2012:284064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yamada M, Sekine S, Matsuda T. Dome-type carcinoma of the colon masquerading a submucosal tumor. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:A30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Winterford CM, Walsh MD, Leggett BA, Jass JR. Ultrastructural localization of epithelial mucin core proteins in colorectal tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:1063-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hou YY, Tan YS, Xu JF, Wang XN, Lu SH, Ji Y, Wang J, Zhu XZ. Schwannoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of 33 cases. Histopathology. 2006;48:536-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marginean F, Rakha EA, Ho BC, Ellis IO, Lee AH. Histological features of medullary carcinoma and prognosis in triple-negative basal-like carcinomas of the breast. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1357-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chetty R. Gastrointestinal cancers accompanied by a dense lymphoid component: an overview with special reference to gastric and colonic medullary and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:1062-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Asmussen L, Pachler J, Holck S. Colorectal carcinoma with dome-like phenotype: an under-recognised subset of colorectal carcinoma? J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:482-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Clouston AD, Clouston DR, Jass JR. Adenocarcinoma of colon differentiating as dome epithelium of gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Histopathology. 2000;37:567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stewart CJ, Hillery S, Newman N, Platell C, Ryan G. Dome-type carcinoma of the colon. Histopathology. 2008;53:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Coyne JD. Dome-type colorectal carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e360-e362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | O’Leary AD, Sweeney EC. Lymphoglandular complexes of the colon: structure and distribution. Histopathology. 1986;10:267-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kealy WF. Colonic lymphoid-glandular complex (microbursa): nature and morphology. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29:241-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kuper CF. Histopathology of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Martin MS, Hammann A, Martin F. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue and 1,2-dimethylhydrazine intestinal tumors in the rat: an histological and immunoenzymatic study. Int J Cancer. 1986;38:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lloyd J, Darzi A, Teare J, Goldin RD. A solitary benign lymphoid polyp of the rectum in a 51 year old woman. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:1034-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Arida M, Barnes EL, Hunt JL. Molecular assessment of allelic loss in Warthin tumors. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:964-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | A R R, Rehani S, Bishen KA, Sagari S. Warthin’s Tumour: A Case Report and Review on Pathogenesis and its Histological Subtypes. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:ZD37-ZD40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Thompson AS, Bryant HC Jr. Histogenesis of papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum (Warthin’s tumor) of the parotid salivary gland. Am J Pathol. 1950;26:807-849. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Chapnik JS. The controversy of Warthin’s tumor. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:695-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Allegra SR. Warthin’s tumor: a hypersensitivity disease? Ultrastructural, light, and immunofluorescent study. Hum Pathol. 1971;2:403-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Warnock GR. Papillary cystadenoma lymphornatosurn (Warthin's tumour). In: Ellis GL, Auclair PL, Gnepp DR (Eds.), Surgical Pathology of the Salivary Glands, W.B. Saunders Company Ltd. Philadelphia 1991; 187-201. |

| 39. | Foulsham CK 2nd, Snyder GG 3rd, Carpenter RJ 3rd. Papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:960-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Martins C, Fonseca I, Roque L, Soares J. Cytogenetic characterisation of Warthin’s tumour. Oral Oncol. 1997;33:344-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Mark J, Dahlenfors R, Stenman G, Nordquist A. Chromosomal patterns in Warthin’s tumor. A second type of human benign salivary gland neoplasm. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1990;46:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Bullerdiek J, Haubrich J, Meyer K, Bartnitzke S. Translocation t(11;19)(q21;p13.1) as the sole chromosome abnormality in a cystadenolymphoma (Warthin’s tumor) of the parotid gland. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1988;35:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Honda K, Kashima K, Daa T, Yokoyama S, Nakayama I. Clonal analysis of the epithelial component of Warthin’s tumor. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1377-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ohmori T, Uraga N, Tabei R. Warthin’s tumor as a hamartomatous dysplastic lesion: a histochemical and immunohistochemical study. Histol Histopathol. 1991;6:559-565. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Bañez EI, Krishnan B, Ansari MQ, Carraway NP, McBride RA. False aneuploidy in benign tumors with a high lymphocyte content: a study of Warthin’s tumor and benign thymoma. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1244-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhou S, Ma Y, Chandrasoma P. Inverted lymphoglandular polyp in descending colon. Case Rep Pathol. 2015;2015:646270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | De Petris G, Leung ST. Pseudoneoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:378-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Guest CB, Reznick RK. Colitis cystica profunda. Review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:983-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yantiss RK, Goldman H, Odze RD. Hyperplastic polyp with epithelial misplacement (inverted hyperplastic polyp): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:869-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tanaka S, Iwamuro M, Kubota J, Goubaru M, Ohta T, Ogata M, Murakami I. Polypoid colonic hamartomatous inverted polyp. Dig Endosc. 2007;19:40-42. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Tamura S, Yano T, Ono F, Yamada T, Higashidani Y, Onishi T, Mizuto H, Yokoyama Y, Onishi S, Moriki T. Inverted colonic mucosal lesion: is this a new entity of colon lesion? Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1814-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Sumathi VP, McCluggage WG. CD10 is useful in demonstrating endometrial stroma at ectopic sites and in confirming a diagnosis of endometriosis. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:391-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Greene FL. Epithelial misplacement in adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1974;33:206-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Muto T, Bussey HJ, Morson BC. Pseudo-carcinomatous invasion in adenomatous polyps of the colon and rectum. J Clin Pathol. 1973;26:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Qizilbash AH, Meghji M, Castelli M. Pseudocarcinomatous invasion in adenomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jass JR. HNPCC and sporadic MSI-H colorectal cancer: a review of the morphological similarities and differences. Fam Cancer. 2004;3:93-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Jass JR, Do KA, Simms LA, Iino H, Wynter C, Pillay SP, Searle J, Radford-Smith G, Young J, Leggett B. Morphology of sporadic colorectal cancer with DNA replication errors. Gut. 1998;42:673-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Knox RD, Luey N, Sioson L, Kedziora A, Clarkson A, Watson N, Toon CW, Cussigh C, Pincott S, Pillinger S, Salama Y, Evans J, Percy J, Schnitzler M, Engel A, Gill AJ. Medullary colorectal carcinoma revisited: a clinical and pathological study of 102 cases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2988-2996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Yamada M, Sekine S, Matsuda T, Yoshida M, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Sakamoto T, Nakajima T, Saito Y, Akasu T. Dome-type carcinoma of the colon; a rare variant of adenocarcinoma resembling a submucosal tumor: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Jass JR, O’Brien J, Riddell RH, Snover DC; Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Recommendations for the reporting of surgically resected specimens of colorectal carcinoma: Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:13-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |