Published online Mar 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.100523

Revised: November 13, 2024

Accepted: December 9, 2024

Published online: March 18, 2025

Processing time: 207 Days and 0.4 Hours

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) is an autoimmune dysfunction caused by genetic and environmental changes that attack the thyroid gland. HT affects approximately 2% to 5% of the population, being more prevalent in women. It is diagnosed through a blood test (anti-thyroid peroxidase). Pharmacological treatment consists of daily administration of the synthetic hormone levothyroxine on an empty stomach. The most common signs and symptoms are: Tissue resistance to triiodothyronine T3, weight gain, dry skin, hair loss, tiredness/fati

To analyze nutritional interventions for treating HT.

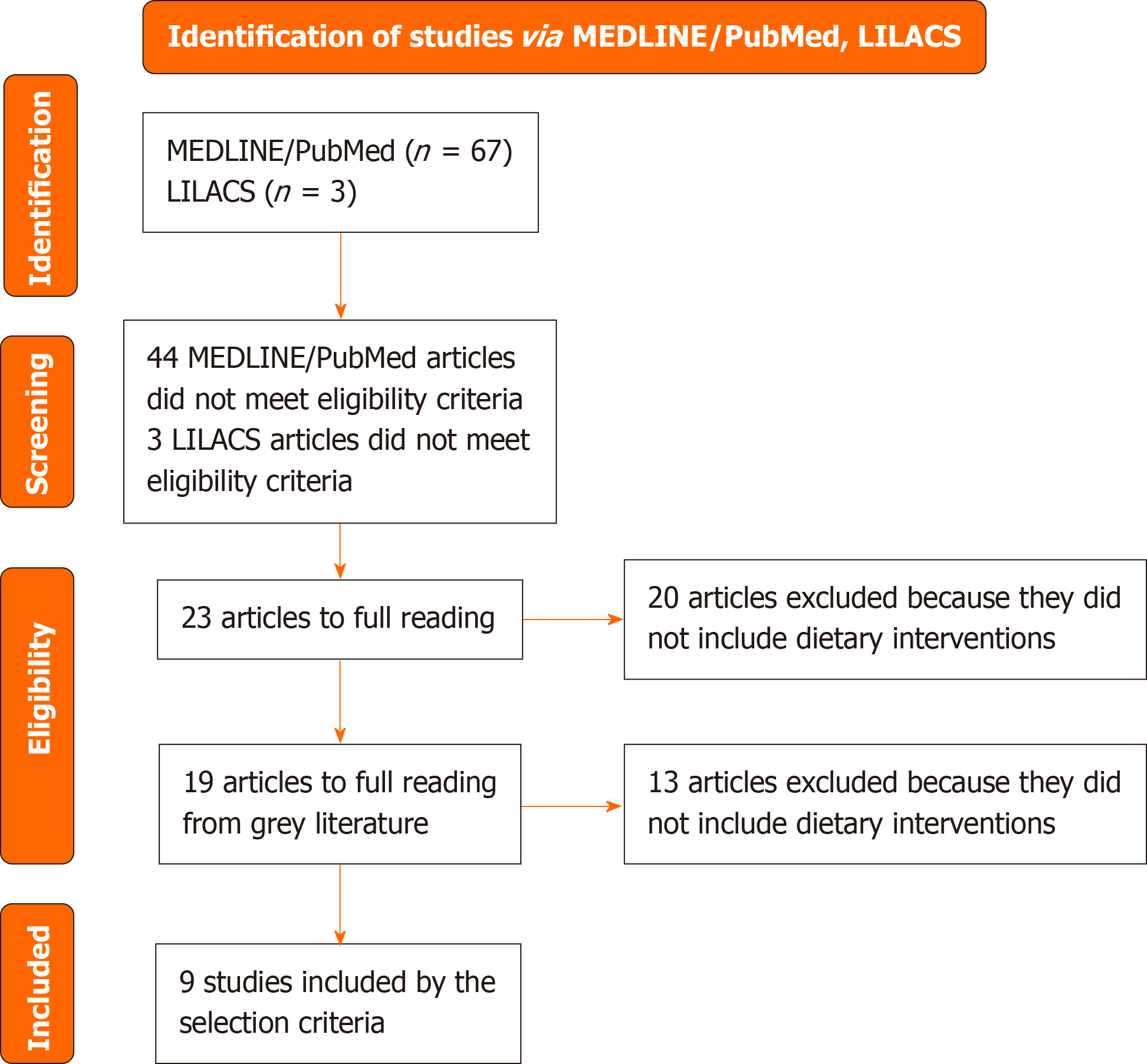

This is an integrative review of original studies on nutritional interventions for treating Hashimoto’s disease. Articles were searched in the MEDLINE/PubMed and Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS) databases via virtual health library, using controlled vocabulary and free terms. A total of 70 articles were found: 67 from PubMed and 3 from LILACS. After exclusions, 9 articles met the eligibility criteria, including dietary interventions for maintaining and restoring the patient’s quality of life.

The reviewed articles evaluated the nutritional treatment of HT through supplementation of deficient micronutrients, anti-inflammatory diets, gluten-free diets, exclusion of foods that cause food sensitivities, lactose-free diet, paleo diet, and calorie restriction diets. However, some results were controversial regarding the beneficial effects of HT.

In general, it was observed that nutritional interventions for HT are based on the recovery of micronutrient deficiencies, treatment of the intestinal microbiota, diet rich in foods with anti-inflammatory properties, lifestyle changes, and encouragement of healthy habits.

Core Tip: The review addresses the efficacy of different dietary approaches in treating Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT). Although gluten and lactose-free diets may benefit some patients, the evidence is controversial and varies according to individual sensitivity and other associated conditions. Paleo diets, which include lifestyle changes and micronutrient supplementation, have improved inflammatory and metabolic interventions in patients with HT. Nutritional interventions focused on anti-inflammatory diets and management of nutritional deficiencies are recommended as complementary alternatives to drug treatment.

- Citation: Santos CS, Carteri RB, Coghetto C, Czermainski J, Rosa CB. Nutritional interventions in the treatment of Hashimoto’s disease: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(1): 100523

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i1/100523.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i1.100523

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) is an autoimmune disorder caused by genetic and environmental alterations that are not yet fully understood and attack the thyroid gland. It is the most common form of hypothyroidism, characterized by complications and chronic thyroid edema, which eventually leads to its dysfunction[1-4]. HT is diagnosed by measuring antithyroid antibodies [anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO)], indicating metabolic alterations in the gland[5].

The thyroid is frequently affected by autoimmune diseases, and patients with autoimmune hyperthyroidism may develop hypothyroidism and vice versa[6].

Subacute thyroiditis may also result in hypothyroidism; however, this condition is usually transient. Approximately 20% to 30% of women with subacute thyroiditis in the postpartum period develop hypothyroidism. The risk increases as anti-TPO antibody levels increase[7].

There is no single definitive cause for this autoimmune disorder, as it involves multiple contributing factors and specific genetic markers. However, early diagnosis can avoid complications, prevent the onset of other autoimmune diseases, and help improve the patient’s quality of life with appropriate treatment[8].

The treatment of HT varies according to the clinical manifestations of the disease, which may include diffuse or nodular goiter with euthyroidism, subclinical hypothyroidism, and permanent hypothyroidism. However, in most cases, and under the prescription of an endocrinologist, levothyroxine should be administered daily, preferably on an empty stomach, to improve drug intake[9].

Nutritional treatment of HT is still often neglected. However, some studies recommend supplementation in cases of nutrient deficiencies such as iodine, iron, copper, selenium, zinc, and vitamin D[9]. Micronutrients are often deficient in autoimmune diseases; therefore, it is important to recommend a diet that meets the deficiencies and nutritional needs[10-12]. Anti-inflammatory diets and the elimination or reduction of specific foods to address potential sensitivities are also being explored in the nutritional therapy for HT[5].

The gut microbiota composition plays a key role in the availability of essential micronutrients for thyroid function[10]. With its vast tissue surface and numerous immune cells interacting with the microbiota, the intestine is central to this process. While the microbiota’s composition is generally stable in adults, it can be influenced by dietary changes and various diseases. More specifically, patients with HT, often present intestinal dysbiosis, as dysregulation of thyroid hormone levels affects the composition of the microbiota, promoting bacterial overgrowth and increased intestinal permeability, ultimately leading to autoimmune processes[10,13,14].

This is an integrative review of original studies that investigated nutritional interventions for the treatment of HT patients. Articles were searched in two databases: The National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health (MEDLINE/PubMed) and the Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS), via the Virtual Health Library (VHL). The search strategy was developed by combining controlled vocabulary and free terms related to: (1) Nutrition; (2) Nutritional Therapy; and (3) Hashimoto’s disease. There was no restriction regarding age group or language. References cited in the articles selected for full reading were reviewed to identify additional studies of interest that may have been missed in the search process (grey literature). Controlled vocabulary was used whenever possible, with health sciences descriptors for VHL and medical subject headings for PubMed. The final search strategy was executed in both databases in June 2024.

This review identified 70 studies, of which 67 were retrieved from MEDLINE/PubMed and 3 from LILACS. Articles that did not focus on nutritional interventions for HT (n = 47) or did not address dietary treatment (n = 20) were excluded. Additionally, 19 articles from grey literature were included, of which 13 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, nine articles met the eligibility criteria, exploring dietary interventions for HT and their impact on patients’ quality of life. Figure 1 graphically presents the results of the study selection process. The diets analyzed by the authors included: Lactose-free[15], gluten-free[16,17], gluten-free combined with healthy habits and nutritional counseling[18], gluten-free with selenium supplementation[19], calorie-restricted diets with or without food exclusion[20], paleo diets excluding grains and dairy products with micronutrient supplementation[21], autoimmune diets with lifestyle modifications[22], and autoimmune paleo diets with calorie restriction up to 1200 kcal[23].

The parameters investigated included: Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxine (fT4), free triiodothyronine (fT3), parathyroid hormone (PTH), TPO antibodies (TPOAb), thyroglobulin antibodies (TgAb), C-reactive protein, vitamins D and B12, zinc, ferritin, lipid profile (high-density lipoprotein-c, low-density lipoprotein-c, triglycerides), symptom questionnaire, quality of life questionnaire, anthropometry [weight and body mass index (BMI)], fasting glucose, and fasting insulin. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the studies included in this review, organized according to the type of treatment investigated.

| Ref. | Country | Type of study | Number of participants, gender and age | Objectives | Groups and treatments | Parameters evaluated | Main results |

| Lactose-free diet | |||||||

| Asik et al[15] | Türkiye | Case-control | 50 patients with HT (Female: 48; Male: 02). Average age: 47.9 ± 8.73 years | To evaluate the prevalence of lactose intolerance in patients with HT and the effects of lactose restriction on thyroid function in these patients | Groups: 1: Lactose intolerant (n = 48); 2: No lactose intolerance (n = 12); Time: 8 weeks | TSH, fT4, calcium, and parathormone (PTH) | The TSH levels decreased in patients with HT and lactose intolerance. Patients without lactose intolerance did not have significant changes in TSH levels. The other parameters did not change after lactose restriction |

| Gluten-free diet | |||||||

| Krysiak et al[16] | Poland | Case-control | 34 women with HT. Average age: Group A = 30 ± 5 years; Group B = 31 ± 6 years | To investigate whether a gluten-free diet affects thyroid function in women with HT | Group A: Gluten-free diet (n = 16); Group B: Gluten-containing diet (n = 18); Time: 6 months | Titers of TPOAb and TgAb; serum levels of TSH, fT3, fT4 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D | In group A, TPOAb and TgAb levels decreased and Vitamin D increased. TSH, fT3, and fT4 levels remained unchanged. In group B, the evaluated parameters remained unchanged |

| Gluten-free diet for patients with CD and HT | |||||||

| Virili et al[17] | Italy | Case report | 103 individuals with HT and/or CD (Female: 92; Male: 11); Age: Patients with HT: 41 (33-51); Patients with HT and CD: 39 (33-50) | To analyze the need to increase fT4 in CD patients adhering to a gluten-free diet | Patients with isolated HT: Gluten-containing diet; Patients with HT and CD: Gluten-free diet; Time: 15 months | TSH, TPOAb, weight and BMI | It was observed that there was a need to increase the fT4 dose by up to 50% in patients with HT and CD who were non-adherent to a gluten-free diet. However, this can be reversed if a gluten-free diet is implemented. Normal thyroid levels were observed after the gluten-free diet, but the same result was obtained after increasing the fT4 dose in patients who were non-adherent to the diet |

| Gluten-free diet associated with healthy lifestyle and nutritional follow-up | |||||||

| Pobłocki et al[18] | Poland | Case-control | 62 women with HT. Average age: 38.86 ± 4.28 years | To evaluate whether the use of a gluten-free diet is effective in patients with HT | Group selection: Gluten-free diet (n = 31); Control group: Average Pole’s diet (n = 31); Time: 12 months | Serum levels of TSH, fT3, fT4, and Titers of TPOAb and TgAb, weight and BMI | There was a reduction in TSH in the study group and an increase in fT4 levels, the other parameters did not change in either group |

| Gluten-free diet with selenium supplementation | |||||||

| Velija et al[19] | United Kingdom | Case-control | 98 women with HT. Average age: 39.60 ± 7.36 years | To validate the positive effect of HT patients adhering to a gluten-free diet and selenium supplementation on the recovery of thyroid function | Group A: Receiving 200 μg selenium in the form of L-selenomethionine orally and gluten-free diet (n = 50); Group B: Receiving 200 μg selenium without any dietary treatment (n = 48); Time: 6 months | Titers of TPOAb and TgAb, and serum levels of TSH, fT3, fT4 | At the end of the study, euthyroidism was restored in 74% of group A participants, and in 58.3% of group B participants. TSH, TPOAb and TgAb levels were significantly reduced in both group after six months of treatment. Serum TPOAb titer in group A had a more significant decrease (by 49%) than those in group B (by 34%) |

| Calorie reduction and food exclusion diet | |||||||

| Ostrowska et al[20] | Poland | Case-control | 100 women with HT and obesity. Average age: Group A = 42.7 ± 10.51 years; Group B = 41.02 ± 11.96 years | To evaluate the influence of calorie reduction diets, with and without food exclusion, on thyroid parameters in women | Group A: Calorie reduction and food exclusion diet (n = 50); Group B: Calorie reduction diet without excluding foods (n = 50). Average reduction of 1000 kcal/day in both diets. Time: 6 months | Titers of TPOab and TgAb, and serum levels of TSH, fT3, fT4, weight and BMI | In both groups, loss of body mass and decrease in BMI were observed, in group A this loss was greater. Both groups obtained decreases in the parameters of TSH, TPOAb, TgAb, and an increase in fT3 and fT4 in group A |

| Paleo diet with exclusion of gluten, grains, dairy and micronutrient supplementation | |||||||

| Avard and Grant[21] | Australia | Case report | Woman with HT, 23 years | To validate whether an approach to modulating the intestinal microbiota and reducing inflammation can be used as methods to regulate intestinal permeability and favor the course of HT treatment | Paleo diet with exclusion of gluten, grains, dairy, low-protein with micronutrient supplementation (vitamin C, D, B1, B4, B5, B6, B12, zinc, selenium, iron a N-Acetyl cysteine) and probiotics. Time: 15 months | Serum levels of TSH, fT4, zinc, ferritin, Vitamin D and B12, Titers of TPOAb and TgAb | Reduction in TSH and TgAb levels and significant improvement in the symptoms that most affected the patient (daytime naps, exhaustion, stress and mood swings, excessive fatigue, hair loss, nighttime insomnia), only intestinal transit, which despite improving, remained unstable |

| Autoimmune diet and lifestyle changes | |||||||

| Abbott et al[22] | United States | Pilot study | 16 women with HT. Average age: 35.6 ± 5.7 years | To determine the efficacy of a multi-disciplinary diet and lifestyle intervention for improving the quality of life,clinical symptom burden, and thyroid function in a population of middle-aged women with HT | Online health coaching program focused on the implementation of a phased elimination diet known as the Autoimmune Protocol. Time: 10 weeks | Complete metabolic profile, serum levels of TSH fT3, fT4, titers of TPOAb, TgAb, CRP, symptom and quality of life questionnaires | No changes in TSH, fT3, fT4, TPOAb, TgAb. Improvement in health and quality of life. Clinical symptoms with significant decrease. In the CRP test there was a decrease of 29% |

| Autoimmune and hypocaloric Paleo diet (1200 kcal) | |||||||

| Al-Bayyari[23] | Jordan | Case report | Woman with HT, 49 years | To observe the effect of a modified paleo immune diet on anthropometry, body composition, insulin, lipid profile and thyroid function of the patient analyzed | Modified autoimmune paleo low-calorie diet (1200 kcal). Time: 6 months | Anthropometric measurements, body composition, fasting blood glucose and insulin, serum levels of HDL-c, LDL-c, triglycerides, fT3, fT4, TSH, and titers of TPOAb | Reduction in anthropometric measurements, body composition, triglycerides, LDL, TSH, TPOAb, and insulin. There were no changes in fT3, fT4. There was an increase in HDL-c |

Firstly, in the study by Asik et al[15], a lactose-free diet demonstrated positive results in patients with lactose intolerance, leading to a reduction in TSH levels but no significant effect on other evaluated parameters, such as fT4, calcium, PTH, and TPOAb titers. Excessive lactose consumption can lead to bacterial overgrowth, gas production, and intestinal distension, potentially impairing T4 absorption. This underscores the rationale for excluding lactose in these patients.

In the study by Krysiak et al[16], the group that followed a gluten-free diet showed a reduction in TPOAb and TgAb levels and an increase in vitamin D levels. These findings suggest a positive effect of gluten exclusion in patients with HT, possibly through the reduction of autoimmunity and increased thyroid production.

This review observed that gluten-free diets support pharmacological treatment of HT in patients with associated celiac disease, reducing the prescribed oral hormone dose by up to 50%. Poor absorption of thyroid medication is common in these patients due to the high permeability caused by the disease in the digestive tract[17]. Also, a gluten-free diet is often recommended for the dietary management of autoimmune diseases, albeit the effects are not immediately evident. For instance, a study by Pobłocki et al[18] examined the effects of a gluten-free diet in combination with healthy habits and nutritional counseling. No significant differences were observed between the control and gluten-free groups until the 12-month mark when the gluten-free group showed reduced TSH levels and increased fT4. These findings suggest that while gluten exclusion is recommended for patients with celiac disease, its use in managing other autoimmune diseases remains controversial, despite its potential to enhance levothyroxine absorption.

Interestingly, Velija et al[19] demonstrated that selenium supplementation significantly reduced TPOAb, TgAb, and TSH levels. Additionally, combining selenium supplementation with a gluten-free diet provided more benefits than supplementation alone in women.

Avard and Grant[21] investigated the association between the restriction of gluten, grains, and dairy products and micronutrient supplementation in women following a paleo diet. Similarly, the case report by Al-Bayyari[23], which also used the paleo diet, demonstrated improvements in thyroid levels and a significant improvement in quality-of-life parameters, including regulation of insomnia, chronic fatigue, stress, exhaustion, hair loss, and bowel movements.

The study that evaluated the “modified autoimmune paleo-diet”[23], combined paleo, vegan, and gluten-free diets. The meal plan contained 1200 kcal/day, with 150 g/day of carbohydrates, 45 g/day of protein, and 47 g/day of lipids, distributed over three daily meals. After 6 months, there was an improvement in parameters related to body mass and adiposity, such as TSH, TPOAb, cholesterol, and insulin, without affecting levels of the thyroid hormones fT3 and fT4. These results favor the treatment of HT, as they reduce inflammation, decrease the need for synthetic fT4, and reduce the risk of associated chronic diseases[23].

Similarly, Abbott et al[22] reported that an “autoimmune protocol”, which is an extension of the paleo diet (removing gluten, and refined sugar, and gradually eliminating pro-inflammatory food groups such as grains, legumes, dairy, eggs, coffee, alcohol, nuts, seeds, sugars, processed foods, oils, and food additives, encouraging the consumption of fresh, nutrient-rich foods, bone broth, and fermentable foods), combined with lifestyle changes, can reduce inflammation and positively assist in the recovery of the immune system weakened by HT. This therapy aims to improve health-related quality of life and reduce disease symptoms.

A Polish study[20] involving 100 women evaluated a hypocaloric diet of up to 1000 kcal/day, with or without the exclusion of foods such as wheat, egg white, cow’s milk, yeast, corn, gluten, peanuts, almonds, egg yolk, shrimp, soy, barley, sheep’s milk, goat’s milk, rice, apple, tomato, mushrooms, hazelnuts, carrots, walnuts, garlic, sesame, cocoa, vanilla, meat, and pineapple. The diet was established through food sensitivity tests and compared to a hypocaloric diet of up to 1000 kcal/day without dietary restrictions[20]. After 6 months of treatment, both groups showed weight loss and reduced adiposity, albeit the group with food exclusion also showed decreased levels of TSH, TPOAb, and TgAb, as well as increased levels of fT3 and fT4 hormones, and higher rates of BMI reduction. This study demonstrated that weight loss benefits the treatment of HT and that an individualized elimination diet potentiates therapeutic results[20].

According to Mikulska et al[24], an anti-inflammatory dietary intervention rich in vitamins and minerals and low in animal-based foods may positively affect the dietary treatment of HT. However, the authors state that no sufficiently reliable studies were found to recommend the exclusion of gluten for all patients with HT. Likewise, Szczuko et al[25] corroborate these findings, stating that it is unsafe to recommend that patients with HT follow this nutritional approach. It is worth noting that a gluten-free diet can be extremely restrictive, difficult to adhere to, and present a high risk of inadequate intake of essential nutrients.

A gluten-free diet, aimed at preventing or treating HT, can lead to deficiencies in some nutrients, as the exclusion of this food group generally results in lower quality and variety in the diet[14]. Additionally, the effects of a gluten-free diet in non-celiac patients with autoimmune diseases have not been sufficiently studied. Some publications suggest that thyroid-related antibodies may respond to a gluten-free diet in patients with both conditions[4]. However, there is insufficient scientific evidence to recommend such a diet for patients with autoimmune diseases other than celiac disease.

On the other hand, it has been reported that, in obese women, a restricted diet excluding pro-inflammatory food groups is more effective than a calorie-restricted diet alone[4,20]. Due to the inflammatory process associated with HT, it seems advisable to prescribe an anti-inflammatory diet in parallel with treatment, in addition to investigating associated autoimmune diseases and deficiencies of micronutrients essential for thyroid function[25].

The results of this review indicate that patients with HT should undergo regular medical follow-up, including tests to monitor vitamins and micronutrients, to assist in managing the progression of the disease. The efficacy of a gluten-free diet in patients with HT is controversial; some studies suggest that gluten exclusion may be beneficial, whereas others have indicated that there is no clear positive impact and may even be associated with disease progression. A lactose-restricted diet may be advantageous for patients with lactose intolerance, but it is unjustified for patients lacking this condition.

Paleodiets, including lifestyle changes and weight reduction, associated with appropriate pharmacotherapy and micronutrient supplementation have satisfactory outcomes. These interventions help reduce the inflammation associated with excess weight, contributing to the progression of HT. The “autoimmune protocol”, excluding pro-inflammatory foods and foods identified as sensitivities, appears to be a favorable approach for treating autoimmune diseases such as HT. However, these dietary strategies are highly restrictive and may be difficult to adhere to.

It is concluded that nutritional interventions based on an anti-inflammatory diet and supplementation of deficient micronutrients may be beneficial alternatives for HT treatment when combined with drug therapy.

| 1. | Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Wartofsky L. Hashimoto thyroiditis: an evidence-based guide to etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2022;132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chaker L, Razvi S, Bensenor IM, Azizi F, Pearce EN, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hiromatsu Y, Satoh H, Amino N. Hashimoto's thyroiditis: history and future outlook. Hormones (Athens). 2013;12:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Passali M, Josefsen K, Frederiksen JL, Antvorskov JC. Current Evidence on the Efficacy of Gluten-Free Diets in Multiple Sclerosis, Psoriasis, Type 1 Diabetes and Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tipu HN, Ahmed D, Bashir MM, Asif N. Significance of Testing Anti-Thyroid Autoantibodies in Patients with Deranged Thyroid Profile. J Thyroid Res. 2018;2018:9610497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vilela LRR, Fernandes DC. Vitamin D and Selenium in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: bystanders or players? Demetra. 2018;13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Vargas-Uricoechea H, Nogueira JP, Pinzón-Fernández MV, Schwarzstein D. The Usefulness of Thyroid Antibodies in the Diagnostic Approach to Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. Antibodies (Basel). 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Hegedüs L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Pearce SH, Weetman AP, Perros P. Primary hypothyroidism and quality of life. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:230-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liontiris MI, Mazokopakis EE. A concise review of Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) and the importance of iodine, selenium, vitamin D and gluten on the autoimmunity and dietary management of HT patients.Points that need more investigation. Hell J Nucl Med. 2017;20:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gong B, Wang C, Meng F, Wang H, Song B, Yang Y, Shan Z. Association Between Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:774362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Knezevic J, Starchl C, Tmava Berisha A, Amrein K. Thyroid-Gut-Axis: How Does the Microbiota Influence Thyroid Function? Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ventura A, Ronsoni MF, Shiozawa MBC, Dantas-corrêa EB, Canalli MHBDS, Schiavon LDL, Narciso-schiavon JL. Prevalence and clinical features of celiac disease in patients with autoimmune thyroiditis: cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2014;132:364-371. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ihnatowicz P, Wątor P, Ewa Drywień M. Supplementation in Autoimmune Thyroid Hashimoto’s Disease. Vitamin D and Selenium. J Food Nutr Res. 2019;7:584-591. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ihnatowicz P, Wątor P, Drywień ME. The importance of gluten exclusion in the management of Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2021;28:558-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Asik M, Gunes F, Binnetoglu E, Eroglu M, Bozkurt N, Sen H, Akbal E, Bakar C, Beyazit Y, Ukinc K. Decrease in TSH levels after lactose restriction in Hashimoto's thyroiditis patients with lactose intolerance. Endocrine. 2014;46:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Krysiak R, Szkróbka W, Okopień B. The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Thyroid Autoimmunity in Drug-Naïve Women with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: A Pilot Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Virili C, Bassotti G, Santaguida MG, Iuorio R, Del Duca SC, Mercuri V, Picarelli A, Gargiulo P, Gargano L, Centanni M. Atypical celiac disease as cause of increased need for thyroxine: a systematic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E419-E422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pobłocki J, Pańka T, Szczuko M, Telesiński A, Syrenicz A. Whether a Gluten-Free Diet Should Be Recommended in Chronic Autoimmune Thyroiditis or Not?-A 12-Month Follow-Up. J Clin Med. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Velija AZ, Hadzovic-dzuvo A, Al TD. The effect of selenium supplementation and gluten-free diet in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism affected by autoimmune thyroiditis. EJEA. 2020;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Ostrowska L, Gier D, Zyśk B. The Influence of Reducing Diets on Changes in Thyroid Parameters in Women Suffering from Obesity and Hashimoto’s Disease. Nutrients. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Avard N, Grant SJ. A case report of a novel, integrative approach to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with unexpected results. AIMED. 2018;5:75-79. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abbott RD, Sadowski A, Alt AG. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet as Part of a Multi-disciplinary, Supported Lifestyle Intervention for Hashimoto's Thyroiditis. Cureus. 2019;11:e4556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Al-Bayyari NS. Successful dietary intervention plan for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: A case study. Rom J Diabetes Nutr Metab Dis. 2020;27:381-385. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Mikulska AA, Karaźniewicz-Łada M, Filipowicz D, Ruchała M, Główka FK. Metabolic Characteristics of Hashimoto's Thyroiditis Patients and the Role of Microelements and Diet in the Disease Management-An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Szczuko M, Syrenicz A, Szymkowiak K, Przybylska A, Szczuko U, Pobłocki J, Kulpa D. Doubtful Justification of the Gluten-Free Diet in the Course of Hashimoto’s Disease. Nutrients. 2022;14:1727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |