Published online Mar 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i9.2153

Peer-review started: January 5, 2021

First decision: March 8, 2021

Revised: March 10, 2021

Accepted: March 15, 2021

Article in press: March 15, 2021

Published online: March 26, 2021

Processing time: 80 Days and 1.8 Hours

Ganglion impar block alone or pulsed radiofrequency alone are effective options for treating perineal pain. However, ganglion impar block combined with pulsed radiofrequency (GIB-PRF) for treating perineal pain is rare and the puncture is usually performed with X-ray or computed tomography guidance.

To evaluate the safety and clinical efficacy of real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF in treating perineal pain.

Thirty patients with perineal pain were included and were treated by GIB-PRF guided by real-time ultrasound imaging between January 2015 and December 2016. Complications were recorded to observe the safety of the ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF procedure, and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at 24 h before and after treatment and 1, 3, and 6 mo later were analyzed to evaluate clinical efficacy.

Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was performed successfully in all patients, and no complications occurred. Compared with pretreatment scores, the VAS scores were significantly lower (P < 0.05) at the four time points after treatment. The VAS scores at 1 and 3 mo were slightly lower than those at 24 h (P > 0.05) and were significantly lower at 6 mo after treatment (P < 0.05). There was a tendency toward lower VAS scores at 6 mo after treatment compared with those at 1 and 3 mo (P > 0.05).

Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was a safe and effective way to treat perineal pain. The 6-mo short-term clinical efficacy was favorable, but the long-term outcomes need future study.

Core Tip: Ganglion impar block alone or pulsed radiofrequency alone are effective options for treating perineal pain. However, the safety and clinical efficacy of real-time ultrasound-guided ganglion impar block combined with pulsed radiofrequency (GIB-PRF) remain unclear. In this study, we evaluated thirty patients with perineal pain who received real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF. Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was found to be a safe and effective method to treat perineal pain, with a favorable 6-mo outcome.

- Citation: Li SQ, Jiang L, Cui LG, Jia DL. Clinical efficacy of ultrasound-guided pulsed radiofrequency combined with ganglion impar block for treatment of perineal pain. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(9): 2153-2159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i9/2153.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i9.2153

Perineal pain is a common complaint, especially in women after delivery[1]. Pain receptors in this region are mainly located within the ganglion impar. Such pain is classified as sympathetic pain, and its treatments include conservative medication, physical treatment, minimally invasive treatment, psychotherapy, and surgical intervention.

Previous studies have reported that ganglion impar pulsed radiofrequency had significant pain relieving effects for refractory perineal pain and coccygeal pain[2,3]. However, the puncture was often guided by X-ray or computed tomography imaging, which have limited effectiveness. The sacrococcygeal joint cannot be precisely visualized by X-ray if the patient has obvious abdominal distension. Although computed tomography can accurately show the position of the puncture needle, it inevitably increases the patient’s exposure to radiation[4,5]. In recent years, ultrasound-guided ganglion impar block was found to be an effective way to treat chronic perineal pain[6], but the patients usually needed three or more repeated blocks[7], which indicated a short duration of pain relief following a single ganglion impar block.

A previous case report observed good outcomes after the use of pudendal nerve block combined with pulsed radiofrequency to treat chronic pelvic and perineal pain[8]. However, the clinical efficacy of real-time ultrasound-guided ganglion impar block combined with pulsed radiofrequency (GIB-PRF) remain unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the safety and clinical efficacy of real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF.

From January 2015 to December 2016, 30 patients with perineal pain or coccygeal pain who were admitted and treated in Peking University Third Hospital were included in our study. Oral painkillers and conservative treatments were ineffective and an ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF procedure was performed. Patients with pelvic disease or histories of surgery, hip trauma, or sacrococcygeal joint fusion and calcification were excluded. All patients provided written informed consent. The study was performed in accord with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the appropriate ethics committee.

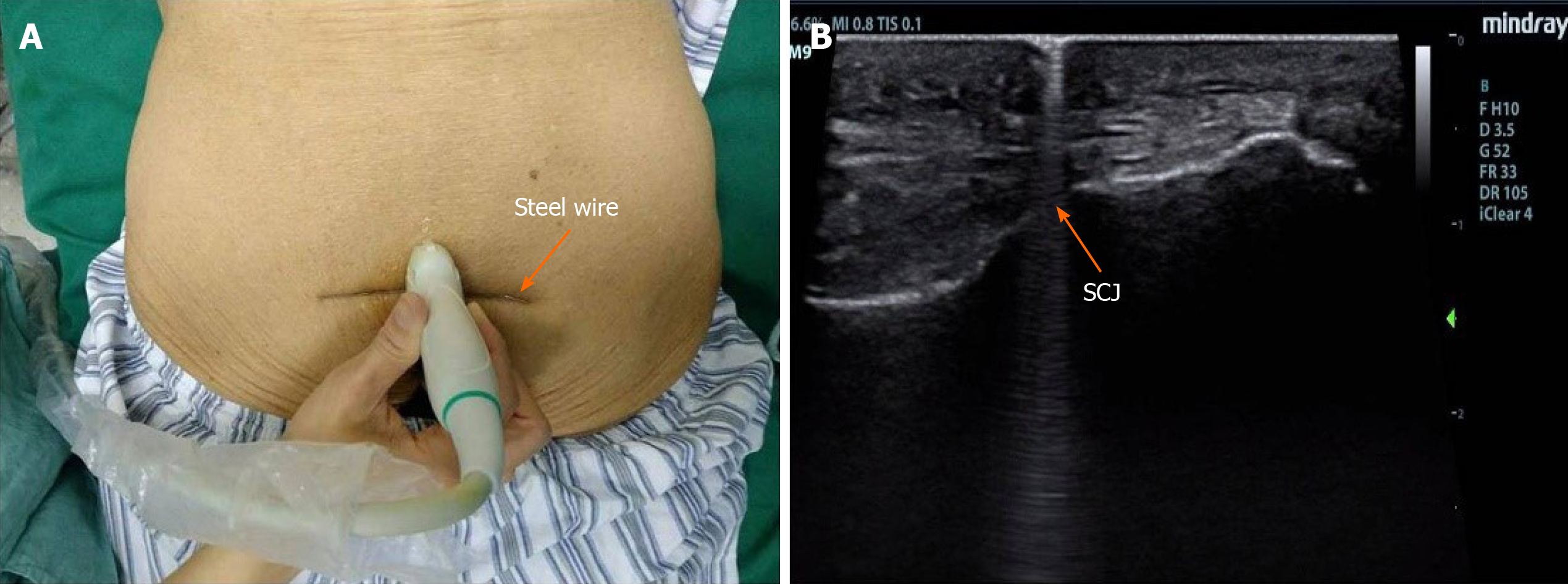

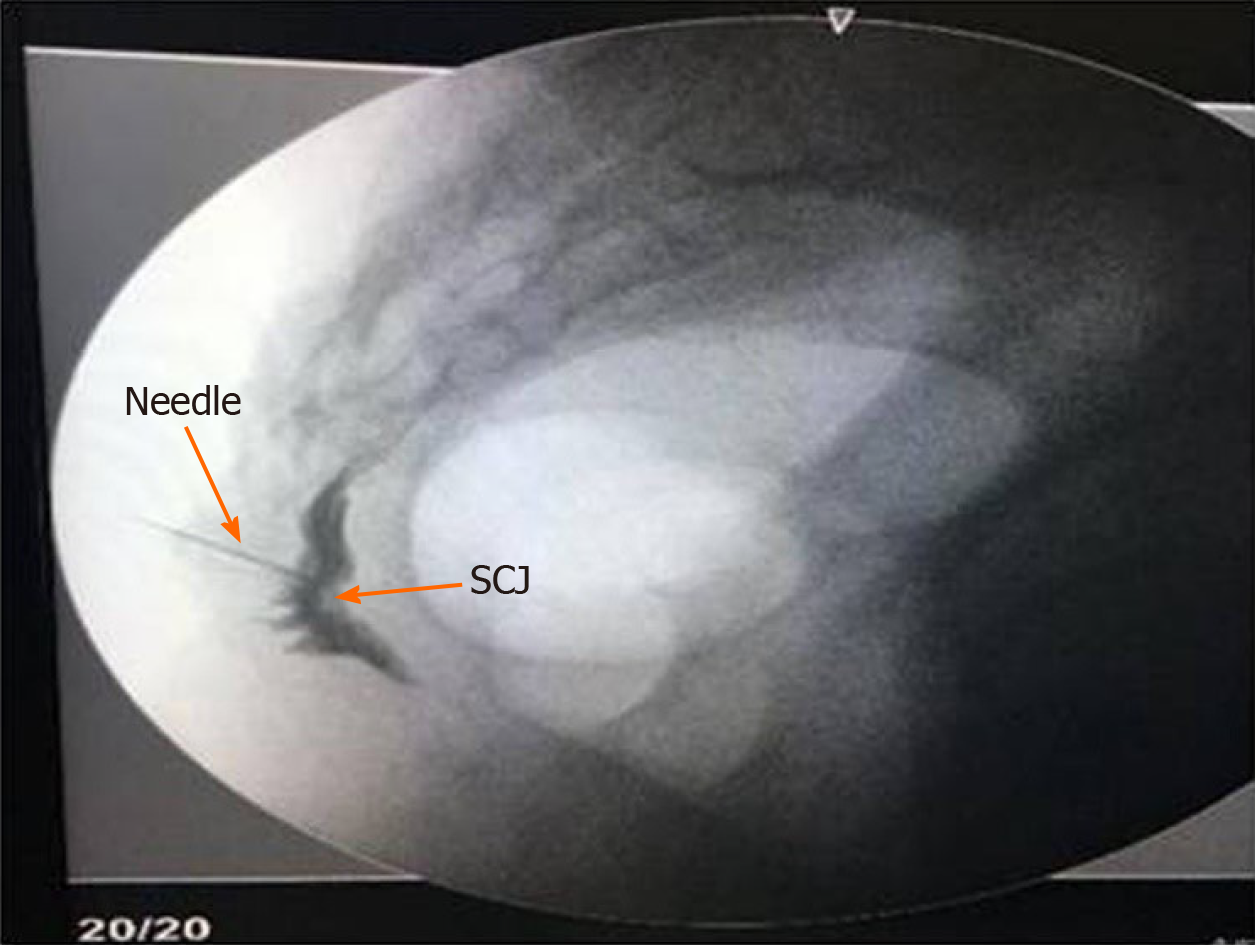

A sterile steel wire was used to assist the positioning over the skin surface. The wire was held perpendicularly to the probe and placed between the probe and skin (Figure 1A). The steel wire was moved until the “comet-tail” sign behind it with overlapping the surface of the sacrococcygeal joint (Figure 1B), which was the precise puncture point of the needle. During insertion, the lift-thrust method was used to find and trace the position of the needle tip. The needle tip was monitored using real-time ultrasound guidance until it reached the space of the sacrococcygeal joint. At that time, slight force was used to push the needle tip into the ventral sacrococcygeal joint disc, which was accompanied by an obvious sensation of fall-through. A lack of resistance was confirmed by the absence of blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or air in a syringe after injection of a small amount of saline. Anteroposterior and lateral contrast scans by a C-arm X-ray unit confirmed the appropriate position of the needle tip (Figure 2).

Sensory stimulation by an all-digital radiofrequency at 50 Hz was started to induce symptoms of perineal pain or discomfort. If the symptoms were consistent with the previous location of pain, the puncture point had reached the position of the ganglion impar. Subsequently, 3 mL of solution containing 0.2% ropivacaine and 2.5 mg diprospan was infused, followed by pulsed radiofrequency treatment for 120 s at 42 ºC. The above procedure was carried out collaboratively by a physician who had specialized in musculoskeletal ultrasound for over 5 years and a surgeon who had specialized in pain therapy for 15 years.

Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores were followed-up at 24 h before and after the treatment, and at 1, 3, and 6 mo after treatment[9]. Surgery-related complications such as rectal perforation, infection, or accidental injection of drugs into the vessels were recorded. These variables were evaluated by resident doctors in the ward or in the outpatient clinic.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, 2011). The data were presented as the mean ± SD for continuous variables. Paired t-tests were used to compare VAS scores before and after treatment at each of two time points. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The mean age of these patients was 62.1 ± 12.1 years. Among the 30 patients, four were male. The mean duration of pain was 17.7 ± 9.1 mo, with a range from 6 to 36 mo.

All 30 patients underwent the procedure uneventfully and without complications such as rectal perforation, infection, or accidental injection of drugs into the vessels. Compared with pretreatment VAS scores, the VAS scores significantly decreased (P < 0.05) at the four evaluations performed after treatment. Compared with the VAS score at 24 h, those obtained at 1 and 3 mo after GIB-PRF treatment tended to be lower (P > 0.05); the scores at 6 mo were significantly lower (P < 0.05). In addition, compared with the VAS scores at 1 and 3 mo, the scores at 6 mo after treatment demonstrated a lower tendency (P > 0.05, Table 1).

GIB-PRF is indicated in patients with perineal pain in whom oral treatment is ineffective, especially those with poor localization of pain, diffuse pain, and symptoms of a burning sensation. The ganglion impar, also called the Walther ganglion or coccygeal ganglion, is located anterior to the sacrococcygeal joint and is a retroperitoneal structure[10]. It is close to the rectum and receives sympathetic neurofibers from the sacrococcygeal area. Our study demonstrated that real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was feasible for treating perineal pain or coccygeal pain, and the key to a success treatment was related to the selection of patients and the tips for ultrasound-guided puncture.

The main principle of pulsed radiofrequency treatment is the generation of a strong electromagnetic field around the tip of the electrode that relieves pain by interfering with the impulse conduction of neurons[11,12], which is one of the effective ways to treat chronic pain. The key step in the procedure is in the precise positioning of the puncture needle within the ganglion impar. X-ray or computed tomography imaging guidance was previously used for the ganglion impar puncture, but the paramedian puncture pathway, which includes the sacrococcygeal joint, coccyx, and anococcygeal ligament, varies. The reported successful puncture rate free of complications is approximately 70%, but none of the puncture methods was generally accepted as the optimal option[13]. In addition, high-frequency ultrasound is usually used to evaluate muscles, tendons, ligaments, and peripheral nerves in clinical practice, and also in the field of pain therapy[14]. Ultrasound-guided ganglion impar blocks were first reported by Gupta et al[15] in 2008 and became an effective treatment for chronic perineal pain[7,16]. However, real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF for treating perineal pain was rarely studied.

Firstly, in our study, the ultrasound-guided method was roughly consistent with that reported by Johnston et al[16]. Local, clear ultrasonograms were obtained by Johnston et al[16], who used high-frequency probes. In our study, significant thickening of subcutaneous soft tissues in the sacrococcygeal area in obese patients prevented clear visualization of the sacrococcygeal joint because of insufficient penetration of the ultrasound waves when using a high-frequency probe. Therefore, we used a low-frequency convex-array probe to increase penetration. The resolution of superficial structures when using a convex-array probe is relatively poor, however, visualization of the target puncture site in the sacrococcygeal joint was satisfactory, which facilitated successful insertion of the needle.

Secondly, the space within the sacrococcygeal joint is narrow and it forms an arc vertically. Thus, the in-plane view of the puncture is limited, regardless of cross-sectionally or vertically scanning. Therefore, we inserted the needle out of plane, which has the advantages of space savings and a short puncture pathway. Although the needle passage cannot be displayed completely, inserting a needle perpendicular to the skin surface is easier for reaching the target, because of the relatively superficial position of the sacrococcygeal joint and the large vertical space of the articular surface. The distance between the skin and sacrococcygeal joint, as measured before insertion, was used as the reference for the depth of insertion and to avoid deep insertion.

Thirdly, another characteristic of our study was the use of a steel wire as a positioning marker. The slender steel wire was visualized on ultrasonograms as a stripe with strong echogenicity, which results from multiple interference of sound waves reflected off the metal surface, generating the “comet-tail” sign. This method greatly enhanced the accuracy of needle positioning. Therefore a careful selection of patients and tips for ultrasound-guided puncture are important to achieve a successful GIB-PRF in patients with perineal pain.

There were also several limitations in this study. Firstly, a relatively small sample size might have led to negative results, especially about post-treatment complications. In addition, this study cannot make a conclusion about superiority of block alone or pulsed radiofrequency alone vs combination of these two treatments, or ultrasound guidance vs X-ray guidance, which need further study. Lastly, a follow-up of more than 6 mo after the GIB-PRF is needed.

Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was a safe and effective way to treat perineal pain. The 6-mo short-term clinical efficacy was favorable. Long-term outcomes need further study.

Despite of the efficacy of ganglion impar block alone or pulsed radiofrequency alone for treating perineal pain, the puncture is usually conducted under the guidance of X-ray or computed tomography imaging. The efficacy of ganglion impar block combined with pulsed radiofrequency (GIB-PRF) for treating perineal pain remains unclear.

This study provides references to the clinical practices of real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF in patients with perineal pain or coccygeal pain.

This study evaluated the safety and clinical efficacy of real-time ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF in treating perineal pain.

Thirty patients with perineal pain who were treated by GIB-PRF with guided by real-time ultrasound imaging were analyzed. Complications were recorded to observe the safety of the treatment. VAS scores at 24 h before and after the treatment, and 1, 3, and 6 mo later were performed to evaluate clinical efficacy.

Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was performed successfully in all patients, and no complications occurred. Compared with pretreatment VAS scores, the VAS scores significantly decreased at the four time points after the GIB-PRF. Compared with the VAS score at 24 h after the GIB-PRF, the scores were slightly lower at 1 and 3 mo and significantly lower at 6 mo after treatment. There was a tendency toward lower VAS scores at 6 mo after GIB-PRF compared with those at 1 and 3 mo.

Ultrasound-guided GIB-PRF was a safe and effective way to treat perineal pain. The 6-mo short-term clinical outcomes were favorable.

The findings from this study help to establish and provide the groundwork for further studies to compare outcomes of block alone or pulsed radiofrequency alone vs the combination of these two treatments and to investigate the long-term outcomes.

The authors would like to thank the members of Department of Pain Medicine and Ultrasound, Peking University Third Hospital.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yang XQ S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Manresa M, Pereda A, Bataller E, Terre-Rull C, Ismail KM, Webb SS. Incidence of perineal pain and dyspareunia following spontaneous vaginal birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:853-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adas C, Ozdemir U, Toman H, Luleci N, Luleci E, Adas H. Transsacrococcygeal approach to ganglion impar: radiofrequency application for the treatment of chronic intractable coccydynia. J Pain Res. 2016;9:1173-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gürses E. Impar ganglion radiofrequency application in successful management of oncologic perineal pain. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:697-699. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Usta B, Gozdemir M, Sert H, Muslu B, Demircioglu RI. Fluoroscopically guided ganglion impar block by pulsed radiofrequency for relieving coccydynia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Datir A, Connell D. CT-guided injection for ganglion impar blockade: a radiological approach to the management of coccydynia. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ghai A, Jangra P, Wadhera S, Kad N, Karwasra RK, Sahu A, Jaiswal R. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of ultrasound-guided ganglion impar block in patients with chronic perineal pain. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Le Clerc QC, Riant T, Levesque A, Labat JJ, Ploteau S, Robert R, Perrouin-Verbe MA, Rigaud J. Repeated Ganglion Impar Block in a Cohort of 83 Patients with Chronic Pelvic and Perineal Pain. Pain Physician. 2017;20:E823-E828. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Lee SH, Lee CJ, Lee JY, Kim TH, Sim WS, Lee SY, Hwang HY. Fluoroscopy-guided pudendal nerve block and pulsed radiofrequency treatment : A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2009;56:605-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gunduz OH, Sencan S, Kenis-Coskun O. Pain Relief due to Transsacrococcygeal Ganglion Impar Block in Chronic Coccygodynia: A Pilot Study. Pain Med. 2015;16:1278-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gopal H, Mc Crory C. Coccygodynia treated by pulsed radio frequency treatment to the Ganglion of Impar: a case series. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2014;27:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Choi YH, Chang DJ, Hwang WS, Chung JH. Ultrasonography-guided pulsed radiofrequency of sciatic nerve for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome Type II. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:83-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li DY, Meng L, Ji N, Luo F. Effect of pulsed radiofrequency on rat sciatic nerve chronic constriction injury: a preliminary study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:540-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang JJ. Another modified approach to the ganglion of Walther block (ganglion of impar). J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:282-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bhatnagar S, Khanna S, Roshni S, Goyal GN, Mishra S, Rana SP, Thulkar S. Early ultrasound-guided neurolysis for pain management in gastrointestinal and pelvic malignancies: an observational study in a tertiary care center of urban India. Pain Pract. 2012;12:23-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gupta D, Jain R, Mishra S, Kumar S, Thulkar S, Bhatnagar S. Ultrasonography reinvents the originally described technique for ganglion impar neurolysis in perianal cancer pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1390-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Johnston PJ, Michálek P. Blockade of the ganglion impar (walther), using ultrasound and a loss of resistance technique. Prague Med Rep. 2012;113:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |