Published online Mar 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1871

Peer-review started: September 16, 2020

First decision: December 21, 2020

Revised: January 3, 2021

Accepted: January 28, 2021

Article in press: January 28, 2021

Published online: March 16, 2021

Processing time: 170 Days and 5.9 Hours

Gastroesophageal varices are a rare complication of essential thrombocythemia (ET). ET is a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) characterized by an increased number of blood platelets.

A 46-year-old woman, who denied a history of liver disease, was admitted to our hospital on presentation of hematemesis. Laboratory examination revealed a hemoglobin level of 83 g/L, and a platelet count of 397 × 109/L. The appearance of gastric and esophageal varices with red colored signs as displayed by an urgent endoscopy was followed by endoscopic variceal ligation and endoscopic tissue adhesive. Abdominal computed tomography revealed cirrhosis, marked splenomegaly, portal vein thrombosis and portal hypertension. In addition, bone marrow biopsy and evidence of mutated Janus kinase 2, substantiated the onset of ET. The patient was asymptomatic with regular routine blood testing during the 6-mo follow-up period. Therefore, in this case, gastroesophageal varices were induced by ET.

MPN should be given considerable attention when performing differential diagnoses in patients with gastroesophageal varices. An integrated approach such as laboratory tests, radiological examination, and pathological biopsy, should be included to allow optimal decisions and management.

Core Tip: Gastroesophageal varices are a rare complication of essential thrombo-cythemia (ET). This report describes a 46-year-old woman who presented with ET-induced esophageal and gastric varies. ET is a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm, which should be given considerable attention when performing differential diagnoses in patients with gastroesophageal varices, in order to allow optimal decisions and management.

- Citation: Wang JB, Gao Y, Liu JW, Dai MG, Yang SW, Ye B. Gastroesophageal varices in a patient presenting with essential thrombocythemia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(8): 1871-1876

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i8/1871.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1871

Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage is a life-threatening complication of portal hypertension, and demands effective and expedited treatment[1]. Cirrhosis is the most common underlying pathology in the progression of portal hypertension-induced gastroesophageal varices[2]. However, not all cases of hypertension are caused by cirrhosis. Obstruction or compression of the splenic vein can also cause non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, resulting in isolated gastric varices[3]. Essential thrombocythemia (ET) rarely causes extensive esophageal and gastric varices, where isolated gastric varices are predominant. In the present study, we report a patient who presented with ET-induced esophageal and gastric varices.

A 46-year-old woman was urgently admitted to our hospital due to presentation of hematemesis.

Hematemesis occurred without obvious inducement, was dark red in color without abdominal pain, and the patient was conscious.

The patient had a history of stroke, but did not have any history of liver disease. She had undergone prior surgery of "endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL)" at another hospital for hematemesis approximately two years ago.

Physical examination revealed the absence of palmar erythema, and spider angioma, and neither the skin nor the sclera was icteric. Abdominal examination revealed that the spleen displayed a third-degree swelling, which was accompanied by slight pain to percussion in the hepatic region.

Laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cell count of 4.7 × 109/L, hemoglobin level of 83 g/L, and a platelet count of 397 × 109/L (normal reference range 125-350 × 109/L), suggesting a significantly increased platelet count. Prothrombin time and liver function tests, as well as bilirubin and albumin levels showed no abnormalities (Table 1). A hepatitis panel was also negative.

| Complete blood count | Liver function tests | Coagulation function | |||

| WBC (109/L) | 4.7 | ALT (U/L) | 25 | PT (s) | 13.5 |

| NEUT, % | 76.7 | AST (U/L) | 22 | APTT (s) | 37.4 |

| LY, % | 12.9 | ALP (U/L) | 56 | ||

| MONO, % | 6.1 | γ-GTP (U/L) | 36 | ||

| EOS, % | 4.1 | ALB (g/L) | 40.8 | ||

| BASO, % | 0.2 | TP (g/L) | 68.5 | ||

| RBC (109/L) | 4.13 | AMY (U/L) | 55 | ||

| Hb (g/L) | 83 | TBil (μmoL/L) | 16.9 | ||

| Ht | 0.276 | HBsAg | (-) | ||

| MCV (fl) | 66.9 | HBsAb | (-) | ||

| MCH (pg) | 20.1 | ||||

| MCHC (g/L) | 301 | ||||

| PLT (109/L) | 397 | ||||

| PRO | (-) | ||||

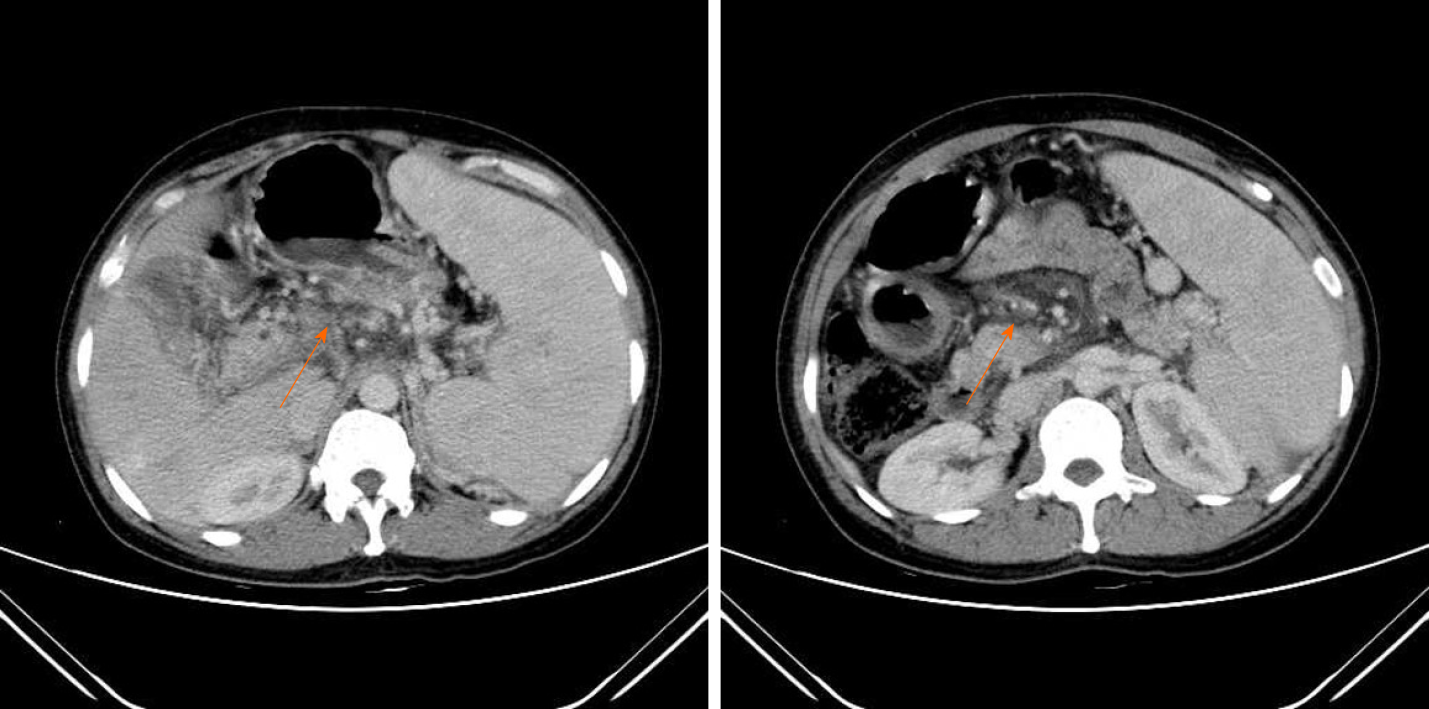

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed cirrhosis, marked splenomegaly, portal vein thrombosis, portal hypertension, and massive collateral blood vessels in the abdominal cavity (Figure 1).

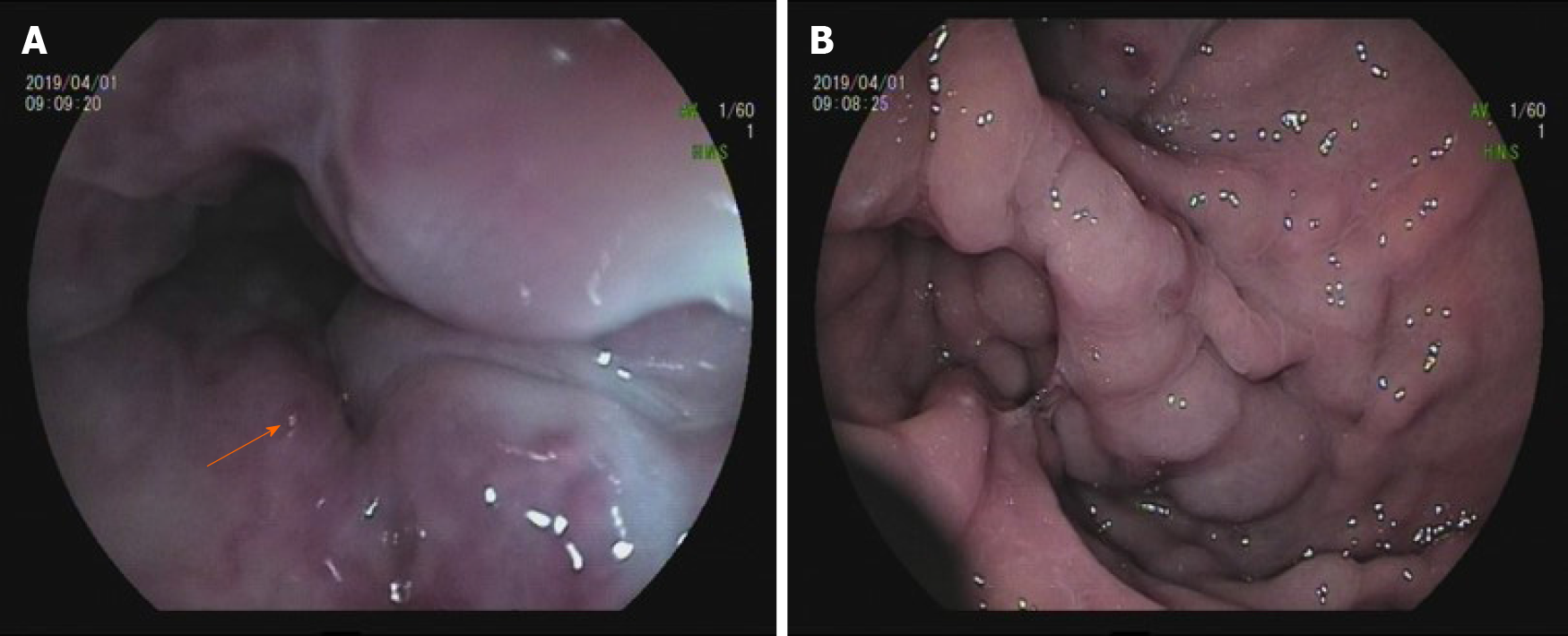

An immediate endoscopy was performed in this patient who was rushed to our hospital on presentation of hematemesis. Endoscopy findings revealed the presence of varicose veins in the middle and lower regions of the esophagus, and the red colored sign (i.e., a hematocystic spot) in the lower esophagus (Figure 2A) and gastric varices (Figure 2B). No active bleeding was found during endoscopy. Thus, EVL and endoscopic tissue adhesive with endoscopic injection of cyanoacrylate glue were performed.

We further analyzed the association between the laboratory findings, abdominal CT, and clinical outcome following endoscopy, and found both an elevated platelet count and splenomegaly which are always associated with hematological diseases.

We considered that the esophageal and gastric varices might be related to hematological diseases. Bone marrow biopsy from the ilium revealed minimal reticulin fibrosis, slightly increased granulocytes and markedly increased megakaryocyte and erythroid counts. Further genetic testing revealed a 40% mutation in Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) V617F. Collectively, these findings led to the diagnosis of ET.

As there were no marked changes in white and red blood cell counts, we advised follow-up with a routine blood examination instead of medical intervention (e.g., hydroxyurea, and anagrelide).

The patient was asymptomatic, and the platelet counts were maintained between 350 × 109/L to 450 × 109/L during the 6-mo follow-up period.

ET, which is a chronic myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) is characterized by an unexplained thrombocytosis with a tendency for thrombosis and hemorrhage[4], and has been reported to be caused by mutations in a variety of genes, and most commonly JAK2 (as observed in this patient)[5]. Varicose vein is a relatively rare phenomenon in ET, especially esophageal and gastric varices. In the present case, the patient repeatedly suffered rupture of esophageal and gastric varices, which was accompanied by marked splenomegaly, in the absence of any typical symptoms of cirrhosis. Laboratory examination suggested an increased platelet count, whereas bone marrow biopsy and genetic tests confirmed the diagnosis of ET. In summary, the patient presented with ET, which is considered a cause of portal hypertension, which subsequently resulted in esophageal and gastric varices.

There are various causes of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, such as obstruction or compression of the splenic vein and portal vein thrombosis[3]. MPN is often accompanied by marked splenomegaly, which might increase the portal vein blood flow which ultimately provokes portal hypertension[6]. Previous reports have demonstrated that a mutation in JAK2 in ET displays decreased blood flow leading to prolonged interactions between the peripheral blood and sinusoidal endothelial cells with a subsequent induced risk of splanchnic venous thrombosis[7]. Furthermore, visceral or portal vein thrombosis might cause portal hypertension. In this case, abdominal CT is an ineffective diagnostic tool for cirrhosis, as the phenotypic characteristics of cirrhosis shown by abdominal CT might be secondary to portal hypertension as caused by ET. Moreover, ET might also cause portal vein thrombosis within or outside of the liver, which leads to portal hypertension[8]. Hence, liver biopsy should be carried out. Based on this case, even if imaging findings suggest cirrhosis, it is important to integrate laboratory examinations and symptoms to make a comprehensive judgment. In addition, histopathological analysis may still be useful to exclude the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

In the present case, the patient repeatedly suffered rupture of gastroesophageal varices, and a recurrence after "esophageal vein rupture repair", which suggested endoscopic treatment alone is ineffective in preventing disease recurrence, since she remained in a state of ill health. Thus, patients with portal hypertension associated with systemic blood disease need to be evaluated at the clinical level, especially in the context of their optimal therapy. As previously reported by others, splenectomy or splenic embolization, and transjugular intrahepatic portal-hepatic venous shunting might be an effective treatment for regional portal hypertension that can induce gastroesophageal varices[9]. However, splenectomy may not be a suitable option when considering the case presented in this study, as splenectomy might further increase the platelet count, which would ultimately aggravate venous thrombosis[10].

As there were no marked changes in white and red blood cell counts, we did not consider any medical intervention to include hydroxyurea and anagrelide. However, in retrospect, we remain confused about whether a more active medical intervention should be selected with the intent of reducing platelet levels, as well as the risk of thrombosis and sequentially the alleviation of portal pressure, regardless of the normal blood cell levels in patients suffering from repeated varicose rupture bleeding. These gaps in the present findings should be formally addressed and warrant further detailed exploration.

ET presenting with portal hypertension may cause gastroesophageal varices. We report this case with the aim of providing some useful diagnostic and treatment-associated source references for clinicians that may encounter similar situations in the clinic.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sarma MS, Swai JD S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Ibrahim M, Mostafa I, Devière J. New Developments in Managing Variceal Bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1964-1969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bosch J, Iwakiri Y. The portal hypertension syndrome: etiology, classification, relevance, and animal models. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hernández-Gea V, Baiges A, Turon F, Garcia-Pagán JC. Idiopathic Portal Hypertension. Hepatology. 2018;68:2413-2423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nimer SD. Essential thrombocythemia: another "heterogeneous disease" better understood? Blood. 1999;93:415-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Morgan KJ, Gilliland DG. A role for JAK2 mutations in myeloproliferative diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | SHALDON S, SHERLOCK S. Portal hypertension in the myeloproliferative syndrome and the reticuloses. Am J Med. 1962;32:758-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khanna R, Sarin SK. Idiopathic portal hypertension and extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:148-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Blendis LM, Banks DC, Ramboer C, Williams R. Spleen blood flow and splanchnic haemodynamics in blood dyscrasia and other splenomegalies. Clin Sci. 1970;38:73-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Khanna R, Sarin SK. Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension - diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2014;60:421-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Hatsuse M, Taminishi Y, Maegawa-Matsui S, Fuchida SI, Inaba T, Murakami S, Shimazaki C. [Latent essential thrombocythemia becoming perceptible after splenectomy]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2019;60:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |