Published online Mar 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1863

Peer-review started: August 30, 2020

First decision: December 21, 2020

Revised: January 3, 2021

Accepted: January 20, 2021

Article in press: January 20, 2021

Published online: March 16, 2021

Processing time: 187 Days and 0.7 Hours

Intradural osteoma is very rarely located in the subdural or subarachnoid space. Unfortunately, intradural osteoma lacks specificity in clinical manifestations and imaging features and there is currently no consensus on its diagnosis method or treatment strategy. Moreover, the pathogenesis of osteoma without skull structure involvement remains unclear.

We describe two cases of intradural osteomas located in the subdural and subarachnoid spaces, respectively. The first case involved a 47-year-old woman who presented with a 3-year history of intermittent headache and dizziness. Intraoperatively, a bony hard mass was found in the left frontal area, attached to the inner surface of the dura mater and compressing the underlying arachnoid membrane and brain. The second case involved a 56-year-old woman who had an intracranial high-density lesion isolated under the right greater wing of the sphenoid. Intraoperatively, an arachnoid-covered bony tumor was found in the sylvian fissure. The pathological diagnosis for both patients was osteoma.

Surgery and pathological examination are required for diagnosis of intradural osteomas, and craniotomy is a safe and effective treatment.

Core Tip: Intradural osteoma is very rarely located in the subdural or subarachnoid space; although, there are disease associations related to sex, ethnicity, and intracranial locations. Intradural osteomas usually require surgery and pathological examination for diagnosis, and craniotomy is considered a safe and effective treatment. In this paper, we describe two cases of intradural osteomas located in the subdural and subarachnoid spaces, respectively, and provide a review of the related literature. The neural crest cell hypothesis is proposed to explain the pathogenesis of this rare tumor localization.

- Citation: Li L, Ying GY, Tang YJ, Wu H. Intradural osteomas: Report of two cases. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(8): 1863-1870

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i8/1863.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1863

Osteomas are benign neoplasms, consisting of normal mature osseous tissue. In the cranial region, osteomas usually occur in the frontal or ethmoid sinuses, arising from the inner or outer table of the cranium[1-3]. However, they are seldom located intradurally without the involvement of skull structure[4-6]. In an extensive search of PubMed, we found only 16 reported cases of intradural osteomas (Table 1).

| Ref. | Age in year, Sex | History of head injury | Symptom | Location | Space position |

| Dukes and Odom[14], 1962 | 43, F | Head injury | Headache | Right frontal | Subdural |

| Vakaet et al[16], 1983 | 16, F | No | Headache and Jacksonian seizures | Frontal | Not available |

| Choudhury et al[15], 1995 | 20, F | No | Headache | Right frontal | Subdural |

| Lee et al[1], 1997 | 28, F | No | Headache | Left frontal | Subarachnoid |

| Aoki et al[8], 1998 | 51, F | No | Headache | Right frontal | Subdural |

| Cheon et al[9], 2002 | 43, F | No | Headache | Left frontal | Subdural |

| Akiyama et al[4], 2005 | 24, M | No | Headache | Right frontal | Subarachnoid |

| Jung et al[10], 2007 | 60, M | No | Headache | Right frontal | Subarachnoid |

| Barajas et al[11], 2012 | 63, F | No | Altered mental status | Right temporal | Subarachnoid |

| Chen et al[17], 2013 | 64, F | No | Tinnitus and dizziness | Right frontal | Parafalx |

| Krisht et al[5], 2016 | 22, F | No | Headache | Left frontal parafalx and anterior skull base | Not available |

| Cao et al[3], 2016 | 54, M | Zygomatic fracture | Dizziness | Right parietal | Subdural |

| Kim et al[2], 2016 | 29, F | No | Headache | Right frontal | Subdural |

| Takeuchi et al[6], 2016 | 40, F | No | Headache | Right frontal | Parafalx |

| Yang et al[12], 2018 | 64, F | No | Dizziness | Left temporal | Subdural |

| Yang et al[12], 2020 | 35, F | No | Headache and fatigue | Right frontal | Subdural |

| Present case 1 | 47, F | No | Headache and dizziness | Left frontal | Subdural |

| Present case 2 | 56, F | No | Accidentally | Right great wing of sphenoid | Subarachnoid |

Here, we augment the literature with this report of two rare cases of intradural osteomas, describing the clinical manifestations, imaging and pathological findings, treatments, and outcomes. Besides highlighting that intradural osteomas not only can occur in the subdural and subarachnoid spaces but also have a unique pattern of intracranial distribution, these cases present the significance of early diagnosis and apposite design of a surgical plan. Finally, we describe how the distribution characteristics of intradural osteomas suggest a pathogenic mechanism, from the perspective of embryogenesis and cell migration.

Case 1: A 47-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of intermittent headache and dizziness.

Case 2: A 56-year-old woman presented with an intracranial high-density lesion that had been incidentally discovered by a computed tomography (CT) scan during routine annual health examination.

Case 1: The experiences of headaches and dizziness had been intermittent and without clear cause but were not severe and had no discernable pattern. The symptoms were sometimes accompanied by nausea and vomiting, and could be relieved by rest. The patient reported that the frequency and severity of symptoms had recently increased slightly.

Case 2: The patient had experienced no subjective symptoms, including headache and dizziness.

Case 1: The patient had undergone a right salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancy 20 years prior, a hysterectomy for uterine fibroids 10 years prior, and appendectomy for appendicitis 2 years prior. She had no history of head trauma.

Case 2: The patient reported having occasional episodes of mild hypertension, for which she was not taking any medication. She had no history of head trauma.

Unremarkable.

Case 1: No significant physical abnormalities or any neurological deficits were observed in the physical examination.

Case 2: The physical examination was unremarkable.

Case 1: No abnormalities were found in routine blood tests, conducted on admission. Biochemical tests revealed minor hyperlipidemia, with a triglyceride level of 1.7 mmol/L (normal range: < 1.69 mmol/L) and low-density lipoprotein of 3.15 mmol/L (normal range: 2.10-3.10 mmol/L), but other liver and kidney function biomarkers were within normal range.

Case 2: The results of routine blood tests on admission were normal. Biochemical tests revealed elevated cholesterol (6.24 mmol/L; normal range: 3.10-6.00 mmol/L) and low-density lipoprotein (3.86 mmol/L; normal range: 2.10-3.10 mmol/L); other liver and kidney function biomarkers were within normal range.

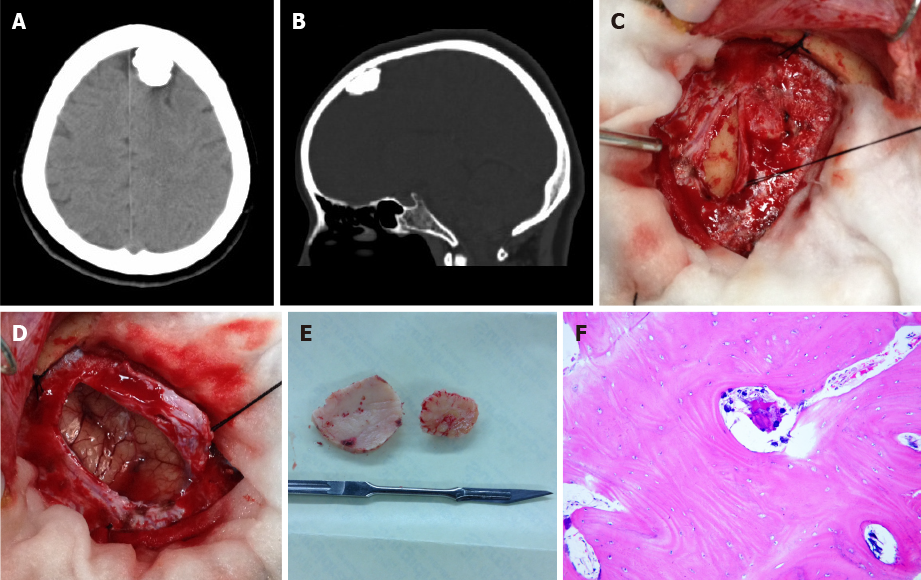

Case 1: A CT scan revealed a high-density rounded lesion in the left frontal area. A curvilinear lucent line was noted between the inner table of the skull and the ossified mass (Figure 1A and B).

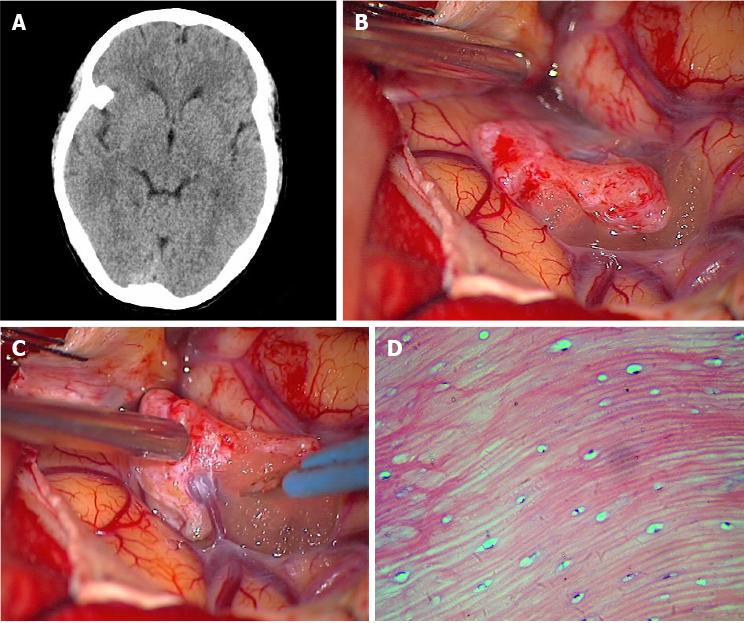

Case 2: A CT scan revealed a homogeneous high-density lesion, isolated under the right greater wing of the sphenoid (Figure 2A). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the mass to be hypointense on both T1weighted and T2weighted imaging, and enhanced with contrast.

Intradural osteoma.

Craniotomy for resection of the tumors, under general anesthesia.

The preliminary diagnosis was calcified meningioma, and a left frontal craniotomy was performed under general anesthesia. Visual inspection following removal of the bone flap revealed no abnormalities besides a bony hard mass, about 2.1 cm × 1.8 cm × 1.1 cm in size, attached to the inner surface of the dura mater. The mass was located in the subdural space and compressing the underlying arachnoid membrane and brain (Figure 1C-E). The mass was separated easily from the dura mater and removed in its entirety.

Postoperatively, the symptoms were relieved and the patient recovered without complication. Pathological examination of the resected lesion indicated osteoma, consisting of mature lamella bone that was composed of the Haver’s system and normal osteocytes between osteoid layers (Figure 1F).

The preliminary diagnosis was intracranial meningioma with calcification. The patient preferred surgical resection of the asymptomatic mass instead of observation, and a right pterional craniotomy was performed. A smooth, bony hard mass, about 1.3 cm × 1.1 cm × 0.8 cm in size, was found in the sylvian fissure, covered by the arachnoid and not associated with the dura. A superficial cortical vein was noted to pass through the mass, which would complicate separation (Figure 2B and C). As such, the vein was sacrificed to facilitate lesion removal, in its entirety, from the fibrous arachnoid attachment.

Pathological examination showed the resected mass to consist mainly of mature bone that was composed of the Haver's system and normal osteocytes (Figure 2D).

For both patients, the postoperative course was uneventful and 6 years of follow-up yielded no signs of tumor recurrence.

Cranial osteomas are benign tumors that form in mature osseous tissues[7], usually arising from the inner or outer table of the skull. Intracranial osteomas located in the subdural or subarachnoid space and without the involvement of the bony structure are very rare. In an extensive search of the literature indexed in the PubMed database, we found only 16 other reports of intradural osteomas; the search strategy involved the years 1962-2020 and search terms of “subdural osteoma”[2,3,8-13], “intradural osteoma”[14,15], “intracerebral osteoma”[1,16], “subarachnoid osteoma”[4], and “intracranial osteoma”[5,17]. In this article, we refer to osteoma located in the subdural or subarachnoid space as intradural osteoma.

For the total 18 cases (16 from the literature and 2 in this report), the age of intradural osteoma patients ranges from 16 to 64 years (mean ± SD: 42.2 ± 15.8 years) and most are female (female:male ratio of 5:1). Although the ethnicity of the patients is rarely mentioned, it is interesting that the majority of case reports (14 cases) are from Asia[13]. Headache or dizziness is the most frequent complaint, which could be a result of irritation or squeezing of the nearby Dural membrane[1]. One of the reported cases had a progressive, altered mental state, and one suffered from headache and Jacksonian seizures. All cases with the symptoms of headache, including our Case 1, were relieved effectively upon surgical removal of the tumors, which suggested that craniotomy was a preferential choice for symptomatic patients.

According to the relative positions of osteomas with the dura and arachnoid, 11 (61%) of the 18 total cases were located in the subdural space (including 2 cases with attachment to the falx) and 5 (28%) in the subarachnoid space; only 2 (11%) were not described in detail. Understanding intracranial osteoma’s occurrence in the subdural or subarachnoid space can help in the design of precise surgical plans for such patients in the future.

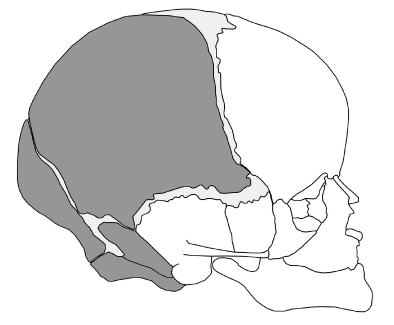

In terms of location of the osteomas, 13 (72%) of the total 18 caseswere under the frontal bone and 1 (6%) had multiple osteomas along the anterior skull base and frontal parafalx region. Two cases had osteoma under the squamous temporal bone. The remaining two had osteoma under the greater wing of the sphenoid and the parietal bone, respectively (Figure 3). The specificity of distribution suggests that its formation may be related to embryonic development. It is worth noting that our data show the osteomas tending to occur on the right side (12 cases; 67%), with 5 cases (28%) on the left and 1 case (6%) in the middle.

High density appearance on CT is one of the characteristics of osteoma. In general, the lucent dural line at the bone window of CT indicates the dura between the skull and the osteoma, which can inform clinicians to differentiate intradural osteoma from meningeal ossification[2,9]. MRI is also helpful in the differential diagnoses[11]. In such, hyperintensity of the lesion on T1-weighted imaging indicates the existence of adipose tissue within the mass[15]; moreover, bone marrow in the lesion can be enhanced with contrast[8]. The calcified meningioma, on the other hand, can be enhanced on MRI and present with the dural tail sign. Another common finding is damage to the bone, which results from extracranial extension[11]. On MRI, meningeal ossification is always multicentric and growing on the dural-falx junction[18]. Despite the above-mentioned differential profiles of imaging features and due to the rarity of cases, most intradural osteomas have been misdiagnosed as calcified meningiomas, meningeal ossification, or skull osteomas before surgery.

The gold standard of intradural osteoma diagnosis is pathological examination of surgically-obtained tissues. Histologically, intracranial osteomas consist of mature lamella bone, composed of the Haver’s system and normal osteocytes. This specific profile differentiates the intradural osteoma from other calcified intracranial lesions[19], but also suggests that the former may be the product of heterotopic transplantation of specific cells during development of the skull[7].

The mechanism that triggers formation of intradural osteomas without bony structure involvement remains unclear. Some of the previous intradural osteoma formation hypotheses have failed to explain the clinical characteristics and specificity of their distribution. Trauma could be a potential provoking event, given the high correlation between intracranial osteoma and trauma history[11]. Dukes and Odom[14] reported a case in which the osteoma arose directly beneath the site of a previous injury, which suggested that a fragment of the periosteum might have penetrated the dura mater and arachnoid to serve as a nidus from which the bony growth arose. However, in the other 17 cases, no history of head trauma was reported. Inflammatory factors and processes may also participate in triggering osteoblastic activities and cause mature bone formation[3,18]. Fallon et al[18] reported that 3% of patients with meningeal osteomas had a history of renal failure, based upon a study of 200 adult autopsies. However, none of the 18 intracranial osteoma cases reported had a history of systemic diseases or metabolic disorders.

Intradural osteoma may be the consequence of localized dural osteogenic activities, given that meninges could function as the periosteum of the inner table of the skull[3,10,12,13,17,18]. Yang et al[12] further argued that the periosteum of the frontal bones and cells from the nasal septum, which contribute to the falx cerebri and the adjacent dura, are derived from the embryological neural crest cells. However, pathological examination revealed that, although the subdural osteoma was attached to the inner surface of dura, the underlying dura was uninvolved with the tumor cells[10].

Another hypothesis was proposed, in which tumor-derived cells are theorized to be strains of primitive mesenchymal cells that have become lost within the neuroectodermal tissue or connective tissue accompanying the blood vessels[16]. Akiyama et al[4] reported data in support of this hypothesis, with their discovery of portions of intradural osteomas being adherent to the superficial cortical veins. According to this theory, however, osteomas should occur in every portion of the skull, with equal chance; in reality, they predominate in the frontal part of the skull. Thus, the mesenchymal hypothesis fails to explain the specific distribution of intradural osteomas.

We speculated that intradural osteomas originate from the heteroplastic primitive neural crest cells. The head mesenchyme stems from both the head mesoderm and neural crest[20,21]. Neural crest cells are specialized, multipotential migratory cells[22,23], from which the anterior cranial bones, such as the frontal, sphenoid, squamous temporal, and facial bones, are derived. The mesoderm directly influences skeletogenesis of the parietal, petrous temporal, and occipital bones[23] (Figure 3). However, a small line of the neural crest remains in the sagittal suture between the two parietal bones and attached to the underlying falx cerebri, serving as growth sites[21,24]; this may explain one case of osteoma that occurred under the parietal bone[3].

According to review of locations of osteomas in the literature, the majority of reported intradural osteomas have been located under the frontal cerebral convexity or at a frontal parafalx site. A small portion have been under the squamous temporal bone, the greater wing of the sphenoid and the parietal bone. All in all, intradural osteomas occur only under the skeletal structure related to neural crest cells, which may not be a mere coincidence. It is reasonable to speculate that embryological cranial neural crest cells might have migrated and generated intradural osteoma during skull development. The migration of cranial neural crest cells is more superficial than that of trunk neural crest cells[23], which would also explain the fact that intradural osteomas only occur in superficial parts of the brain, such as the subdural space or subarachnoid space. This new hypothesis could explain the histological manifestation and distribution specificity of intradural osteomas, and can also represent a new perspective from which we may gain a better understanding of the skull formation during embryonic development.

Intradural osteoma may well be an under-reported entity, but the rare cases reported have suggested trends related to sex, ethnicity, and intracranial sites. This raises the question regarding what are the other drivers of this particular tumor, including genetic, environmental, or other factors? To begin to answer this, neurosurgical societies should collaborate and establish registries for collating data on patients with such rare tumors. The study of signaling pathways in and osteogenic potential of neural crest cells may be a productive direction for the future research.

Intradural osteoma has characteristic imaging features but requires surgery and pathological examination to confirm the diagnosis. Craniotomy is a safe and effective procedure for intradural osteoma. Considering the entire cohort of 18 cases reported, the location of intradural osteomas is consistent with neural crest cell distribution during the formation of the skull. This neural crest cell hypothesis, in which intradural osteoma may originate from embryological neural crest cells and migrate to the subdural space or subarachnoid space to form an intradural osteoma during skull development, is proposed to explain its pathogenesis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Verran DJ S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Lee ST, Lui TN. Intracerebral osteoma: case report. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:250-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim EY, Shim YS, Hyun DK, Park H, Oh SY, Yoon SH. Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Findings of Subdural Osteoma: A Case Report. Brain Tumor Res Treat. 2016;4:40-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cao L, Hong L, Li C, Zhang Y, Gui S. Solitary subdural osteoma: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:1023-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akiyama M, Tanaka T, Hasegawa Y, Chiba S, Abe T. Multiple intracranial subarachnoid osteomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:1085-9; discussion 1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Krisht KM, Palmer CA, Couldwell WT. Multiple osteomas of the falx cerebri and anterior skull base: case report. J Neurosurg. 2016;124:1339-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takeuchi S, Tanikawa R, Tsuboi T, Noda K, Miyata S, Ota N, Hamada F, Kamiyama H. Surgical case of intracranial osteoma arising from the falx. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:1949-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hakim DN, Pelly T, Kulendran M, Caris JA. Benign tumours of the bone: A review. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aoki H, Nakase H, Sakaki T. Subdural osteoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:727-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheon JE, Kim JE, Yang HJ. CT and pathologic findings of a case of subdural osteoma. Korean J Radiol. 2002;3:211-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jung TY, Jung S, Jin SG, Jin YH, Kim IY, Kang SS. Solitary intracranial subdural osteoma: intraoperative findings and primary anastomosis of an involved cortical vein. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14:468-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Barajas RF Jr, Perry A, Sughrue M, Aghi M, Cha S. Intracranial subdural osteoma: a rare benign tumor that can be differentiated from other calcified intracranial lesions utilizing MR imaging. J Neuroradiol. 2012;39:263-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang H, Niu L, Zhang Y, Jia J, Li Q, Dai J, Duan L, Pan Y. Solitary subdural osteoma: A case report and literature review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;172:87-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang YN, Gu Z, Song YL. Intracranial subdural osteoma. Eur J Inflam. 2020;18:1-5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | DUKES HT, ODOM GL. Discrete intradural osteoma. Report of a case. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Choudhury AR, Haleem A, Tjan GT. Solitary intradural intracranial osteoma. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:557-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vakaet A, De Reuck J, Thiery E, vander Eecken H. Intracerebral osteoma: a clinicopathologic and neuropsychologic case study. Childs Brain. 1983;10:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen SM, Chuang CC, Toh CH, Jung SM, Lui TN. Solitary intracranial osteoma with attachment to the falx: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fallon MD, Ellerbrake D, Teitelbaum SL. Meningeal osteomas and chronic renal failure. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:449-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pau A, Chiaramonte G, Ghio G, Pisani R. Solitary intracranial subdural osteoma: case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 2003;89:96-98. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kuratani S. The neural crest and origin of the neurocranium in vertebrates. Genesis. 2018;56:e23213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 567] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jin SW, Sim KB, Kim SD. Development and Growth of the Normal Cranial Vault: An Embryologic Review. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59:192-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mishina Y, Snider TN. Neural crest cell signaling pathways critical to cranial bone development and pathology. Exp Cell Res. 2014;325:138-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Slater BJ, Lenton KA, Kwan MD, Gupta DM, Wan DC, Longaker MT. Cranial sutures: a brief review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:170e-178e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |