Published online Mar 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1835

Peer-review started: November 11, 2020

First decision: December 3, 2020

Revised: December 11, 2020

Accepted: January 14, 2021

Article in press: January 14, 2021

Published online: March 16, 2021

Processing time: 113 Days and 22.2 Hours

The success rate of conservative endodontic management for root fracture varies greatly based on different methods used. It has been rarely reported that calcium silicate-based materials are applied in root fracture treatment.

A 38-year-old male patient presented with spontaneous pain from the upper left anterior teeth for 1 wk. The spontaneous pain was subsequently relieved, but pain on mastication persisted for 3 d. The patient had a dental trauma from a boxing match 15 years ago. Cone beam computed tomography showed that the maxillary left central incisor had oblique fracture lines and a radiolucent lesion around the fracture line. The tooth was diagnosed with an oblique root fracture with no healing and symptomatic apical periodontitis. In the following conservative endodontic management, the coronal and apical fragments of the canal both were chemo-mechanically prepared and obturated using a single cone gutta-percha with iRoot SP (Innovative BioCreamix Inc, Vancouver, Canada), a new calcium silicate-based bioceramic root canal sealer. At follow-ups at 1, 6, 12, and 24 mo, the patient was asymptomatic and the radiolucency around the fracture line was healing radiographically.

Conservative root canal treatment is an alternative treatment in some cases of oblique root fracture with no healing. The application of bioceramic sealers and single core obturation techniques may also be essential to obtain an excellent outcome.

Core Tip: This case report describes conservative endodontic management of a delayed oblique root fracture in a maxillary central incisor. In this delayed root fracture case, the coronal and the apical fragments of the canal were both chemo-mechanically prepared and obturated using a single cone gutta-percha with iRoot SP, a new calcium silicate based bioceramic root canal sealer. At follow-ups at 1, 6, 12, and 24 mo, the patient was asymptomatic and the radiolucency around the fracture line was healing radiographically. Conservative root canal treatment should be considered as an alternative treatment in some cases of oblique root fracture with no healing. The application of bioceramic sealers and single core obturation techniques may also be essential to obtain an excellent outcome.

- Citation: Zheng P, Shen ZY, Fu BP. Conservative endodontic management using a calcium silicate bioceramic sealer for delayed root fracture: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(8): 1835-1843

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i8/1835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i8.1835

Traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) of permanent teeth, which occur frequently in children and young adults, have presented a challenge to clinicians worldwide. Consequently, proper diagnosis, treatment planning, and follow-up are critical to assure a favorable outcome[1]. The incidence rate of root fractures in traumatic permanent teeth is approximately 0.5%-7%[2]. There are four types of healing of root factures: (1) Healing with hard tissue; (2) Healing with interposition of hard and soft tissue; (3) Healing with interposition of only soft tissue; and (4) No healing[3]. The management of root fractures is usually to stabilize the tooth when the pulp is vital. If the pulp is necrotic, surgical and endodontic treatment is feasible. Similarly, regular follow-up is indispensable[1,4].

Conservative endodontic management with root fracture was first reported in 1958[5]. Since then, four types of conservative endodontic treatment have been described: (1) Preparing and gutta-percha (GP) filling the coronal fragment only; (2) Preparing and GP filling of the root canal in both fragments; (3) Preparing and GP filling of the root canal of the coronal fragment and removing of the apical fragment surgically; and (4) Dressing the root canal with calcium hydroxide followed by filling with GP. Cvek et al[5] reported that the frequency of healing was 76% in the first type, zero in the second type, 68% in the third type, and 86% in the fourth type. However, the selection and roles of root canal sealers (RCSs) in the obturation have not been reported.

New types of sealers containing mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) and calcium silicate (CS) have been developed. MTA has demonstrated satisfactory outcomes for the endodontic treatment of intra-alveolar root fractures[6]. However, several shortcomings of MTA have been reported, such as the potential release of hazardous substances, the potential for discoloration, and the inconvenience of handling[7,8]. IRoot SP (Innovative BioCreamix Inc, Vancouver, Canada) is a novel premixed, injectable, CS-based bioceramic RCS composed of calcium phosphate, calcium hydroxide, zirconium oxide, and thickening agent[9]. In endodontic treatment, CS-based sealers with the single cone obturation technique can promote apical healing, possess antibacterial activity, bond to tooth structure, and even enhance osteoblastic differentiation[10,11]. Sealer properties may benefit the healing after root fracture.

This case report presents conservative endodontic management of a delayed oblique root fracture by applying iRoot SP and single cone obturation.

A 38-year-old male patient presented with spontaneous pain from the upper left anterior teeth for 1 wk. The spontaneous pain was subsequently relieved, but pain on mastication persisted for 3 d.

The patient had dental trauma from a boxing match 15 years ago, which led to fracture of both maxillary central incisors’ crowns. At that time, he only received restorative treatment at a clinic due to incisal angle defects. Then, he experienced repeated pain at the upper anterior teeth, which could be relieved by taking anti-inflammatory drugs until this appointment.

The patient had a free previous medical history. He had a history of multiple dental treatments, but details were not available.

The patient had a free personal and family history.

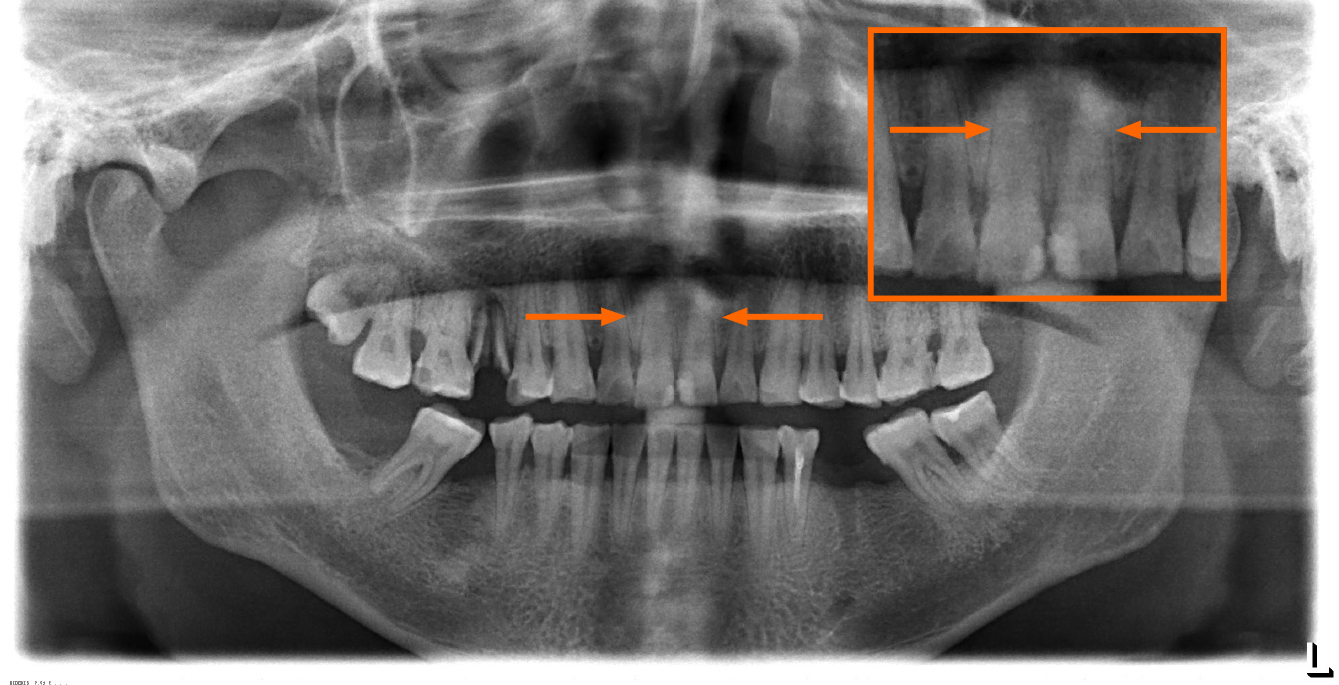

The composite resin restorations in the mesial incisalangle of both maxillary central incisors were stable, but the margins were stained (Figure 1). Clinical examination of teeth #9 (maxillary left central incisor, the universal numbering system) and #8 (maxillary right central incisor) revealed a probing depth of 2 mm, bleeding on probing (-), and no mobility. However, tooth #9 was very sensitive to percussion and did not respond to clod vitality test and electric pulp test. Tooth #8 was asymptomatic and responded normally to clod stimulation and electric pulp test as control teeth.

X-ray images (Figure 2) and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT, Figure 3) revealed that both of the maxillary central incisors had oblique fracture lines, and the coronal portion had no dislocation. A 3 mm × 4 mm radiolucent lesion was noted around the fracture line of the tooth #9. The sagittal pictures of CBCT showed fenestration at the labial of the fracture line. However, no lesion could be found around the periapical condition or fracture line of the tooth #8.

According to the clinical examination and radiography, the diagnosis for tooth #9 was oblique root fracture with no healing, and symptomatic apical periodontitis. In addition, the diagnosis for tooth #8 was root fracture.

Two treatment plans for tooth #9 were provided for the patient. One is endodontic surgery (removing the apical fracture part, reverse root canal preparation, and obturation), and the other one is conservative endodontic management. The patient accepted the latter treatment plan. In addition, long-term observation was necessary for tooth #8.

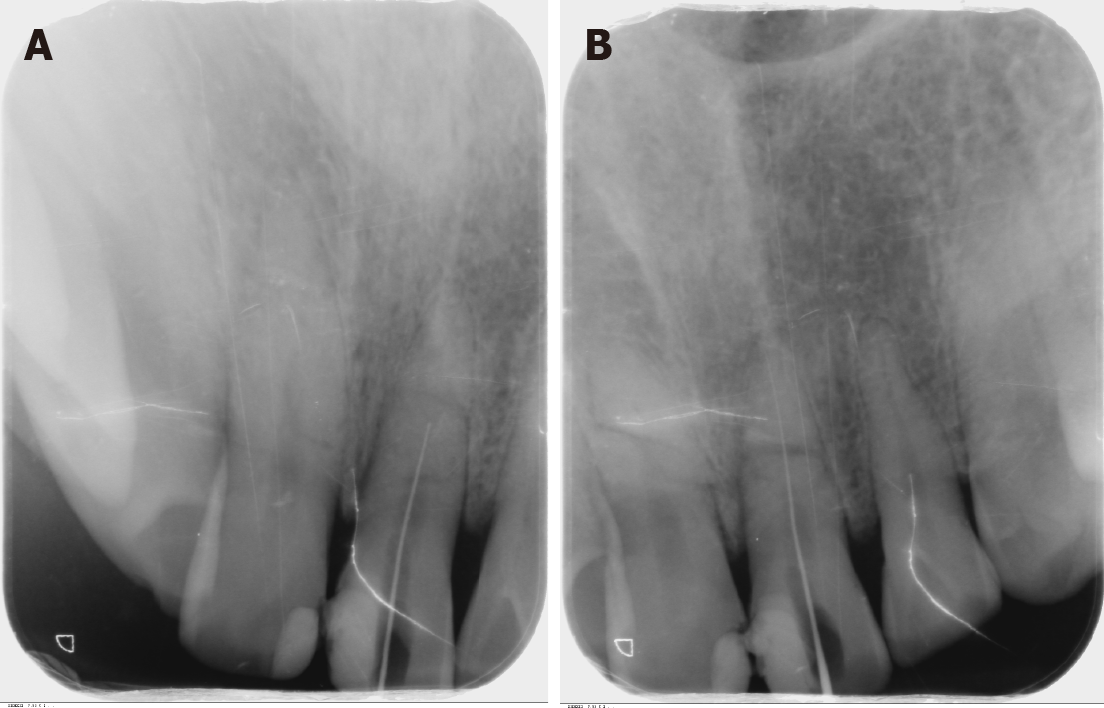

After access preparation without anesthesia initially, the patient felt pain when the #10 K-file entered 13 mm into the root canal. The radiograph showed that the file stopped at the fracture area (Figure 4A), which implied that the pulp of the apical fragment was still vital. Then, under local anesthesia, the working length (WL) was determined to be 19 mm (Figure 4B). The root canal was prepared until Protaper F3 (Protaper Universal, Dentsply, Switzerland). Sodium hypochlorite solution (3%; Susun, Harbin QuanKang Medicine Company, China) and 17% EDTA (root canal lubricating solution, LongLy Biotechnology, China) were used for irrigation. After the coronal and the apical fragments had been chemo-mechanically prepared, the root canal was dried and dressed in calcium hydroxide paste (Multi-Cal, Pulpdent Corporation, United States). The pulp cavity was sealed with glass ionomer cement (Fuji IX GP, GC, Japan).

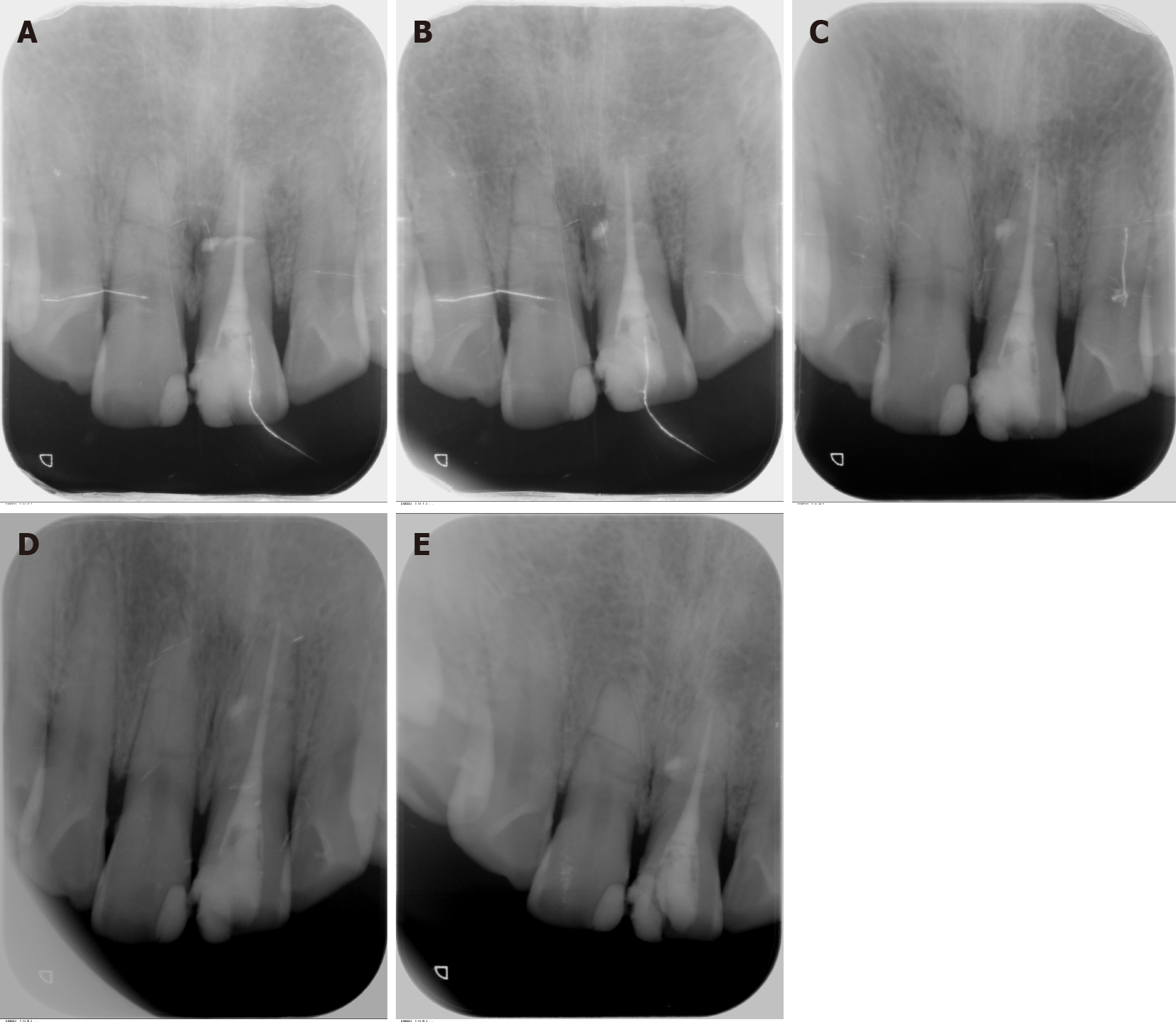

A week later, the patient returned the second appointment. He presented with no pain on mastication. Tooth #9 was not sensitive to percussion or palpation and had no mobility or swelling. After removing intracanal dressing and irrigation using ultrasonic instruments (SUPRASSON P5 NEWTRON, Satelec, France), the root canal was dried and completely injected with iRoot SP. Then, No. 3006 GP (Bio GP Points, Sure Dent Corporation, Korea) was inserted as single core obturation technique. The immediate postoperative radiograph showed that the root canal was filled correctly in WL without voids and overfilled to the radiolucent lesion area near the root fracture line by the sealer (Figure 5A). Finally, the cavity was closed with composite resin (Filtek Z350XT, 3M, United States).

At the 1-mo follow-up (Figure 5B), the patient was functional with no pain or mobility. The radiograph showed that the periapical lesion around the fracture line of tooth #9 still existed but was not extended. At follow-ups at 6 mo (Figure 5C), 12 mo (Figure 5D), and 24 mo (Figure 5E), the tooth #9 was asymptomatic and functional. The radiolucent lesion was healing, and the fracture line still existed but was indistinct in the radiograph. At the 24-mo follow-up, partial defects in the resin restoration were noted, and gaps could be detected around the margin. However, the patient refused to undergo further restoration using resin or other ceramics.

In the current case report, the successful outcome was based on radiographical aspects associated with clinical conditions: The elimination of symptoms and evidence of bony healing[12]. According to the criteria listed by Andreasen et al[13], tooth #9 might heal with hard tissue (fracture line is not visible or indistinctly outlined from the radiograph). Endodontic treatment with bioceramic sealers and single core obturation techniques may be beneficial to the healing of root fractures.

Periapical radiographs and panoramic radiographs can be applied to evaluate root fractures. Then, CBCT was used to obtain a more accurate diagnosis, which was in accordance with the position statement of the European Society of Endodontology and American Association of Endodontists[14,15]. CBCT has demonstrated great abilities to reveal the location and the type of root fracture, and to investigate the condition of the alveolar bone[16]. In this case, it played a fundamental role in deciding treatment planning and judging prognosis. In particular, the root canal from the coronal to the apical part was still a straight path from a three-dimensional image, offering the possibility of preparing both the coronal and apical parts.

According to the chief complaint, clinical examination, and radiography, both maxillary central incisors were diagnosed with root fractures. Interestingly, tooth #8 was functional and asymptomatic without any effective treatment. Cases of healing of root fractures without treatment have been reported[17-20]. The vitality of the pulp tissue improves the healing of the root fracture[2]. In this case, tooth #8 still responded to electric pulp test. It is an important factor why it could heal spontaneously.

The frequency and type of healing depend on the maturity of the root, type of injury, diastasis between the fragments, and optimal repositioning of dislocated fragments. Immature teeth, no dislocation, and less diastasis are positive for healing[21]. In the present case, the coronal fragment was almost in the normal position, and the diastasis between the fragments was very small. The root of this tooth was mature with an oblique root fracture. The lesion around the fracture had no communication with the oral environment. Depending on the situation of this tooth, we tentatively judged the prognosis and treatment of the tooth. Although root fracture could be treated by endodontic surgery successfully, endodontic treatment is more conservative[22].

Root fracture always leads to pulp necrosis. However, apical fracture part generally remains vital[21]. In some cases, only randomized controlled trials are applied to the coronal fragment, resulting in satisfactory healing[23,24]. But it is difficult to achieve proper mechanical cleansing and adequate filling of the coronal fragment, because an apical stop is impossible to achieve[5].

Bruno et al[25] demonstrated that 85% of non-vital traumatized teeth presented microorganisms in the root canal with intact crowns. To eliminate infectious pulp tissue and inflammatory tissue between the fragments as much as possible and prevent apical pulp infection by coronal necrotic pulp tissue, both apical and coronal fragments were prepared and disinfected. A relatively sterile environment that was beneficial to the healing of the lesion was formed by this process. Therefore, if the root canals of both fragments are a straight path that can be well prepared, preparing and filling in both fragments are reasonable. Cvek et al[5] reported that all the seven cases in which both fragments were prepared and filled failed to heal. The material for obturation in their report was chloropercha and 5% resin-chloroform, which may influence the effect of the treatment.

IRoot SP is a biocompatible and nontoxic material that includes similar compositions to MTA and has both excellent physical properties, even in an inflamed acidic environment[26,27]. CS molecules within iRoot SP undergo hydration reactions that generate calcium hydroxide, which can inhibit pathogenic microorganisms and then react with phosphate, causing the precipitation of hydroxyapatite. Chang et al[11] reported that bioceramic sealers can induce superior osteoblastic differentiation with less of an inflammatory response[28]. In this case, iRoot SP was overfilled to the fracture line and alveolar bone destruction area, which did not affect or hinder the healing of the lesion. Ricucci et al[29] also reported the absence of inflammatory or foreign body reactions of the host tissues in contact with CS-based sealers. Wound healing was rapid with repair of lost tissues with cementum and new bone trabeculae. This finding may be attributed to the highly biocompatible and bioactive nature of the sealers.

Cold lateral or warm vertical condensation techniques may not represent appropriate obturation methods for root fracture cases, because pressure can lead to the movement of the fragments and GP may be squeezed into the fracture line. The acceptance of single cone obturation technique with CS root canal sealers has recently increased. A comparable success rate compared to warm vertical condensation technique has been reported[30]. The present case suggests that the single core technique is an effective treatment option for fractured root canal obturation.

It is generally accepted that coronal leakage can permit bacterial elements to penetrate root fillings and result in the failure of endodontic treatments. At the 24-mo follow-up of this case, the resin restoration was not intact. However, coronal leakage did not affect the healing of inflammatory lesions. Regardless of whether the resin defect was caused by additional trauma or secondary caries, the coronal seal might be broken. It is necessary to seal the crown promptly. However, longer observations should reveal the long-term effects of the endodontic treatments[31].

This successful case illustrates that conservative root canal treatment may represent an alternative treatment in some cases of oblique root fracture with no healing. The following requirements should be the recommendations of the cases: Mature root, no dislocation, minimal diastasis, and no oral communication with the lesion around the fracture area. The application of bioceramic sealers and the single core obturation technique might also be essential to obtain an excellent outcome.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dioguardi M S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, Kenny DJ, Trope M, Sigurdsson A, Andersson L, Bourguignon C, Flores MT, Hicks ML, Lenzi AR, Malmgren B, Moule AJ, Pohl Y, Tsukiboshi M. Guidelines for the Management of Traumatic Dental Injuries: 1. Fractures and Luxations of Permanent Teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2017;39:401-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Mejàre I, Cvek M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures. 1. Effect of pre-injury and injury factors such as sex, age, stage of root development, fracture type, location of fracture and severity of dislocation. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:192-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Mejàre I, Cvek M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures. 2. Effect of treatment factors such as treatment delay, repositioning, splinting type and period and antibiotics. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:203-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Malhotra N, Kundabala M, Acharaya S. A review of root fractures: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Dent Update. 2011;38:615-616, 619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cvek M, Mejàre I, Andreasen JO. Conservative endodontic treatment of teeth fractured in the middle or apical part of the root. Dent Traumatol. 2004;20:261-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim D, Yue W, Yoon TC, Park SH, Kim E. Healing of Horizontal Intra-alveolar Root Fractures after Endodontic Treatment with Mineral Trioxide Aggregate. J Endod. 2016;42:230-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Parirokh M, Torabinejad M. Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review--Part III: Clinical applications, drawbacks, and mechanism of action. J Endod. 2010;36:400-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Parirokh M, Torabinejad M, Dummer PMH. Mineral trioxide aggregate and other bioactive endodontic cements: an updated overview - part I: vital pulp therapy. Int Endod J. 2018;51:177-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ersahan S, Aydin C. Solubility and apical sealing characteristics of a new calcium silicate-based root canal sealer in comparison to calcium hydroxide-, methacrylate resin- and epoxy resin-based sealers. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:857-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al-Haddad A, Che Ab Aziz ZA. Bioceramic-Based Root Canal Sealers: A Review. Int J Biomater. 2016;2016:9753210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang SW, Lee SY, Kang SK, Kum KY, Kim EC. In vitro biocompatibility, inflammatory response, and osteogenic potential of 4 root canal sealers: Sealapex, Sankin apatite root sealer, MTA Fillapex, and iRoot SP root canal sealer. J Endod. 2014;40:1642-1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Molven O, Halse A, Grung B. Observer strategy and the radiographic classification of healing after endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Andreasen JO, Hjorting-Hansen E. Intraalveolar root fractures: radiographic and histologic study of 50 cases. J Oral Surg. 1967;25:414-426. [PubMed] |

| 14. | European Society of Endodontology, Patel S, Durack C, Abella F, Roig M, Shemesh H, Lambrechts P, Lemberg K. European Society of Endodontology position statement: the use of CBCT in endodontics. Int Endod J. 2014;47:502-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Special Committee to Revise the Joint AAE/AAOMR Position Statement on use of CBCT in Endodontics. AAE and AAOMR Joint Position Statement: Use of Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Endodontics 2015 Update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;120:508-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cohenca N, Simon JH, Roges R, Morag Y, Malfaz JM. Clinical indications for digital imaging in dento-alveolar trauma. Part 1: traumatic injuries. Dent Traumatol. 2007;23:95-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chala S, Sakout M, Abdallaoui F. Repair of untreated horizontal root fractures: two case reports. Dent Traumatol. 2009;25:457-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fagundes Ddos S, de Mendonça IL, de Albuquerque MT, Inojosa Ide F. Spontaneous healing responses detected by cone-beam computed tomography of horizontal root fractures: a report of two cases. Dent Traumatol. 2014;30:484-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Görduysus M, Avcu N, Görduysus O. Spontaneously healed root fractures: two case reports. Dent Traumatol. 2008;24:115-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Makowiecki P, Witek A, Pol J, Buczkowska-Radlińska J. The maintenance of pulp health 17 years after root fracture in a maxillary incisor illustrating the diagnostic benefits of cone bean computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2014;47:889-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cvek M, Mejàre I, Andreasen JO. Healing and prognosis of teeth with intra-alveolar fractures involving the cervical part of the root. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | S S, Patel PV, Kumar S. The management of a persistent periapical lesion caused by an apicomarginal defect, associated with a root end fracture in an endodontically treated tooth: a clinical report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1593-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brito-Júnior M, Camilo CC, Soares JA, Souza LN, Moreira-Júnior G, Faria-e-Silva AL. Endodontic management of a long-standing horizontal mid-root fracture: case report in a young patient. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:69-71. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Er K, Celik D, Taşdemir T, Yildirim T. Treatment of horizontal root fractures using a triple antibiotic paste and mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:e63-e66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bruno KF, de Alencar AH, Estrela C, Batista Ade C, Pimenta FC. Microbiological and microscopic analysis of the pulp of non-vital traumatized teeth with intact crowns. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gandhi B, Halebathi-Gowdra R. Comparative evaluation of the apical sealing ability of a ceramic based sealer and MTA as root-end filling materials - An in-vitro study. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9:e901-e905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tian J, Zhang Y, Lai Z, Li M, Huang Y, Jiang H, Wei X. Ion Release, Microstructural, and Biological Properties of iRoot BP Plus and ProRoot MTA Exposed to an Acidic Environment. J Endod. 2017;43:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yuan Z, Zhu X, Li Y, Yan P, Jiang H. Influence of iRoot SP and mineral trioxide aggregate on the activation and polarization of macrophages induced by lipopolysaccharide. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ricucci D, Grande NM, Plotino G, Tay FR. Histologic Response of Human Pulp and Periapical Tissues to Tricalcium Silicate-based Materials: A Series of Successfully Treated Cases. J Endod. 2020;46:307-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zavattini A, Knight A, Foschi F, Mannocci F. Outcome of Root Canal Treatments Using a New Calcium Silicate Root Canal Sealer: A Non-Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ricucci D, Gröndahl K, Bergenholtz G. Periapical status of root-filled teeth exposed to the oral environment by loss of restoration or caries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:354-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |