Published online Feb 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1455

Peer-review started: November 4, 2020

First decision: December 13, 2020

Revised: December 13, 2020

Accepted: December 27, 2020

Article in press: December 27, 2020

Published online: February 26, 2021

Processing time: 93 Days and 20.6 Hours

Almost 80 percent of adults in the United States have had cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection by age 40. The number of symptomatic CMV hepatitis cases has been increasing along with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) cases in the United States that is estimated to be 25 percent of the population. In this paper, we try to link these two entities together.

In this case report, we describe a young female who presented with fever, nausea, and vomiting who was found to have NAFLD and CMV hepatitis that was treated supportively.

In this case report, we describe NAFLD as a risk factor for CMV hepatitis and discuss the possible impact on clinical practice. We believe, it is essential to consider NAFLD and it’s disease mechanisms’ localized immu-nosuppression, as a risk factor of CMV hepatitis and severe coronavirus disease 2019 infection.

Core Tip: It is essential to consider non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and it’s disease mechanisms’ localized immunosuppression, as a risk factor of cytomegalovirus hepatitis and possible other viral diseases. Also, with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease raising numbers it is worthwhile to screen for it in high risk population to prevent from it's complications and risks to develop severe viral diseases in case of infection that could be life threatening.

- Citation: Khiatah B, Nasrollah L, Covington S, Carlson D. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for cytomegalovirus hepatitis in an immunocompetent patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(6): 1455-1460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i6/1455.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i6.1455

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a herpesviridae family member that causes a spectrum of human illness that is mostly dependent on the host. Infection in an immunocompetent patient is usually asymptomatic or might present as a mononucleosis syndrome. Occasionally, primary CMV infection can lead to severe organ-specific complications with significant morbidity and mortality[1,2]. CMV hepatitis in immunocompetent patients has been reported frequently in the literature, increasing the awareness of this disease[3]. Reports over the last decade have informed us that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a multisystem disease affecting multiple extrahepatic organs and regulatory pathways, proving that NAFLD's clinical burden is not limited to liver-related morbidity and mortality[4]. NAFLD is an excessive infiltration of fat in the liver in individuals not consuming or consuming in small amounts of alcohol defined as ≤ 20 g per day for women and ≤ 30 g per day for men. Diagnosis usually requires the elimination of secondary causes of fatty infiltration of the liver, including hepatitis C virus infection, the use of glucocorticoids, celiac disease, Wilson disease, familial hypobetalipoproteinemia, and autoimmune disorders[5].

Six-day history of fever, night sweats, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting.

A 34-year-old Hispanic female presents to the emergency room (ER) with a six-day history of fever, night sweats, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting. Coronavirus disease 2019 testing was negative, and she was sent home on antiemetics. She developed intermittent abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant of 5/10 intensity, sharp, non-radiating associated with mild headache and lightheadedness that prompted her to return to the ER. She has no sick contacts. She is up to date on her vaccinations, monogamous, practices all social distancing precautions, and is a housewife and a mother of 3 healthy children. She denies having pain with any specific foods, including fatty foods, recent travel, IV drug abuse, alcohol, smoking, and all other symptoms. Her only medications were Ondansetron and Acetaminophen.

Remote history of intermittent asthma.

Family history is remarkable for diabetes.

On physical exam, her body mass index is 33.1 kg/m²; she has a temperature of 101.2 F and is mildly tender to palpation in the epigastric area. Otherwise, her physical exam is benign.

Laboratory studies are shown in Table 1 and 2.

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 (discharge day) | |

| Hemoglobin (range 12.0-16.0 g/dL) | 14.6 | 12.8 | 12.6 |

| White blood count (range 4.8-10/8 k/µL) | 11.4 | 8.9 | 9.0 |

| Platelet count (range 150-400 k/µL) | 173 | 156 | 162 |

| Serum sodium (range 135-145 mEq/L) | 133 | 133 | 133 |

| Serum bicarbonate (range 24-30 mEq/L) | 25 | 22 | 22 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (range 8-26 mg/dL) | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Creatinine, serum (range 0.5-1.5 mg/dL) | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.81 |

| Protein, serum (g/dL) (range 6.0-8.5 g/dL) | 6.7 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| Albumin, serum (g/dL) (range 3.4-4.8 g/dL) | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| Alanine aminotransferases (range 5-40 unit/L) | 319 | 234 | 200 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (range 9-48 unit/L) | 210 | 130 | 118 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (range 53-128 unit/L) | 372 | 302 | 314 |

| Total bilirubin (range 0.2-1.2 mg/dL) | 1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Direct bilirubin (range 0-0.3 mg/dL) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Test | Result |

| Hepatitis A IgM | Negative |

| Hepatitis Be Antigen | Negative |

| Hepatitis Be antibody | Negative |

| Hepatitis C | Negative |

| Hepatitis E antibody IGG | Detected |

| Hepatitis E antibody IGM | Negative |

| HIV antibody | Negative |

| Blood culture | Negative |

| Urine culture | Negative |

| Pregnancy test, Urine | Negative |

| Serum CMV DNA PCR (normal range < 200.00 IU/mL) | 13700 IU/mL |

| Cytomegalovirus IgM (normal range < 29.9 U/mL) | 47.7AU/mL |

| Influenza A and B rapid test | Negative |

| Epstein-Barr virus DNA PCR (Negative) | Negative |

| HIV-1/2 antibody/antigen | Negative |

| SARS-COV-2 IGM/IGG | Negative |

| Acetaminophen (range 10-30 µg/mL) | < 10 µg/mL |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative |

| Anti-smooth muscle antibody | Negative |

| Anti-mitochondrial | Negative |

| Tissue transglutaminase antibody | Negative |

| Liver kidney microsomal assay (negative range ≤ 20.0 units) | < 20.0 units |

| Ferritin | 384 ng/mL |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (range 0-30.0 mm/h) | 16 mm/h |

| 24 h Urine Copper (3.0-45.0 µg/d) | 48 µg/d |

| C-reactive protein (0.00-0.80 mg/dL) | 5.8 mg/dL |

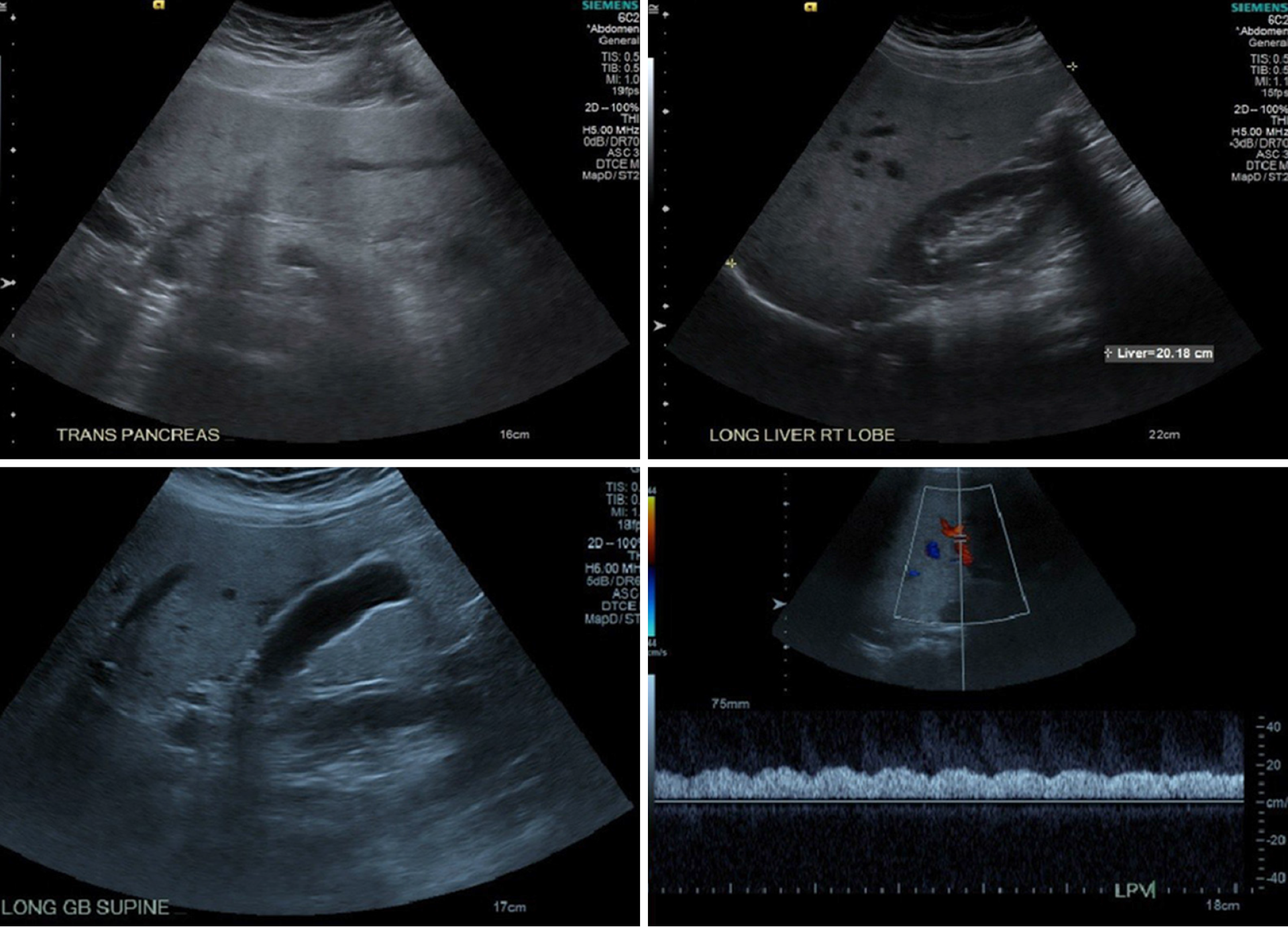

Radiologic studies revealed fatty liver, as shown in Figure 1 and 2, compared to normal liver imaging in 2015.

CMV Hepatitis in the setting of NAFLD. She is admitted for observation and found to have CMV hepatitis, as shown in Table 1 and 2.

Supportive treatment with Ibuprofen 400 mg every 6 h for fever.

She was discharged home and instructed to follow up with both her primary care doctor and the Gastroenterologist. Education was provided on a low-fat diet, exercise, and the importance of weight loss. One week after discharge, she was seen in the primary clinic for follow up. She reported continuous yet less frequent symptoms of fever, myalgias, and night sweats controlled with Acetaminophen, Ibuprofen, and Ondansetron. Her liver enzymes were trending down. Two weeks after discharge, she was symptom-free with normalized liver enzymes.

The liver is a unique immune environment containing lymphocytes, monocytes, Kupffer cells, Natural-killers, astrocytes dendritic, and many other immigrant cells associated with the immune system. It is responsible for synthesizing various proteins such as acute-phase proteins, complements, cytokines, chemokines, lipid messengers, and reactive oxygen species. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, endotoxins from the intestinal flora, and genetic predispositions are all involved in developing NAFLD, causing an imbalance of the immune system in the liver[4,5]. This imbalance translates as an elevation of Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-15, IL-17, IL18, Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha, Interferon gamma-induced protein 10, and Transforming growth factor beta-3[5]. A recently published study where authors reported NAFLD's significance as a significant risk factor affecting the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 emphasizes the importance of this imbalance[6].

Finally, in the United States, with an estimated 25 percent of the population with NAFLD, and almost 80 percent of adults having CMV infection by age 40, it is essential to consider NAFLD and it’s disease mechanisms’ localized imm-unosuppression, as a risk factor of CMV hepatitis. Further studies and research are required to understand NAFLD as a risk for viral diseases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Schmitz SMT S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G, Snover D, Rudnick H, Balfour HH Jr, Mazur MH, Watson R, Schwartz B, Muller N. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of cytomegalovirus-induced mononucleosis in previously healthy individuals. Report of 82 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1986;65:124-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cohen JI, Corey GR. Cytomegalovirus infection in the normal host. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:100-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wreghitt TG, Teare EL, Sule O, Devi R, Rice P. Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1603-1606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Byrne CD, Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62:S47-S64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1516] [Cited by in RCA: 2140] [Article Influence: 214.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kosmalski M, Mokros Ł, Kuna P, Witusik A, Pietras T. Changes in the immune system - the key to diagnostics and therapy of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2018;43:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boettler T, Marjot T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, Maticic M, Cordero E, Jalan R, Moreau R, Cornberg M, Berg T. Impact of COVID-19 on the care of patients with liver disease: EASL-ESCMID position paper after 6 months of the pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |