Published online Dec 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11220

Peer-review started: June 7, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 5, 2021

Accepted: November 15, 2021

Article in press: November 15, 2021

Published online: December 26, 2021

Processing time: 199 Days and 2.3 Hours

In 2020, the world faced the unprecedented crisis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Besides the infection and its consequences, COVID-19 also resulted in anxiety and stress resulting from severe restrictions on economic and social activities, including for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). Fresh acute stress exerts stronger influences than continuous stress on UC patients. We therefore hypothesized that the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic would have serious effects on UC patients and performed this retrospective control study.

To determine whether the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic would have serious effects on UC patients included in a retrospective controlled study.

A total of 289 consecutive UC outpatients seen in March and April 2020 were included in this study. Modified UC disease activity index (UC-DAI) scores on the day of entry and at the previous visit were compared. An increase of ≥ 2 was considered to indicate exacerbation. The exacerbation rate was also compared with that in 256 consecutive control patients independently included in the study from the same period of the previous year in the same manner.

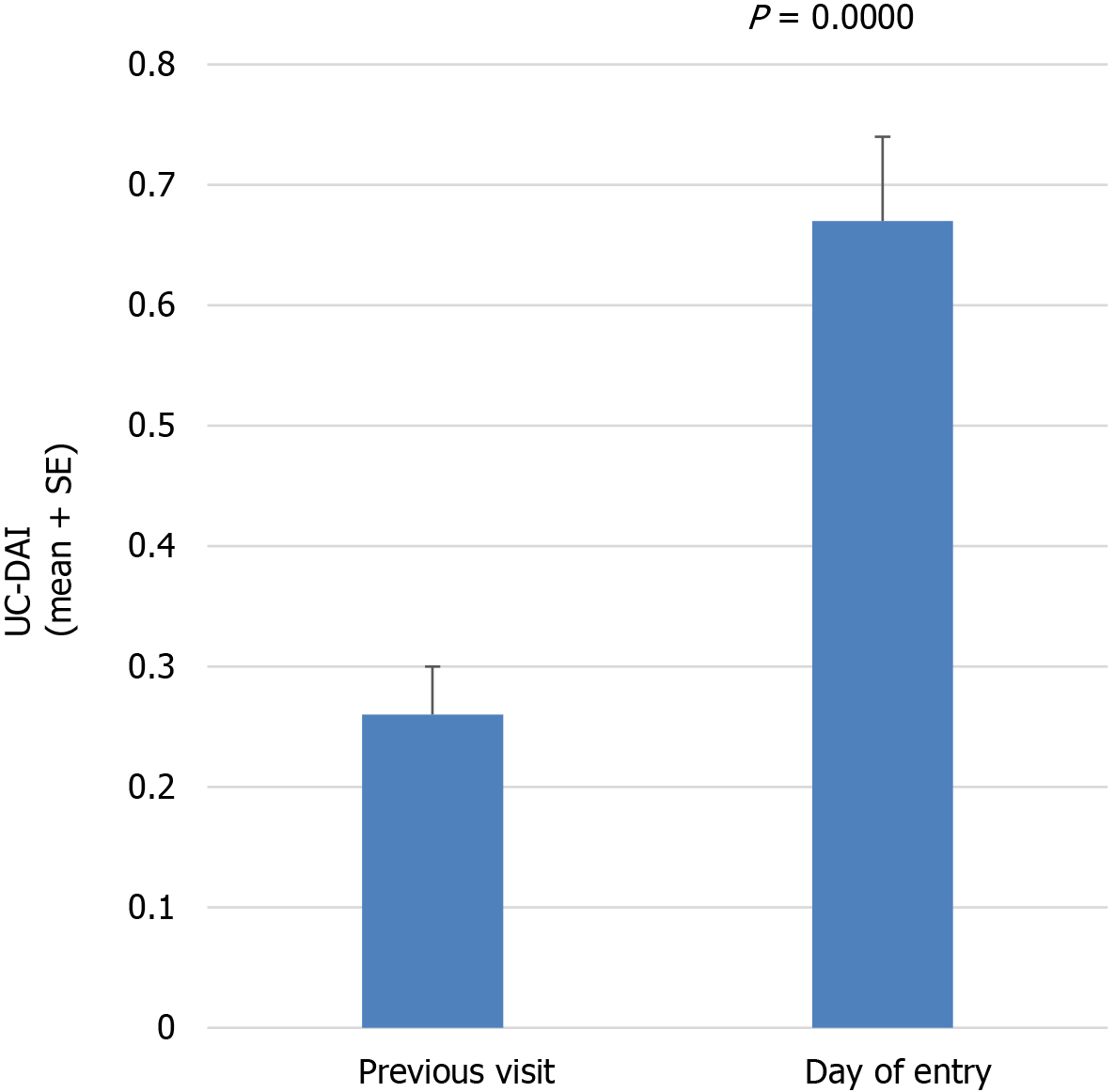

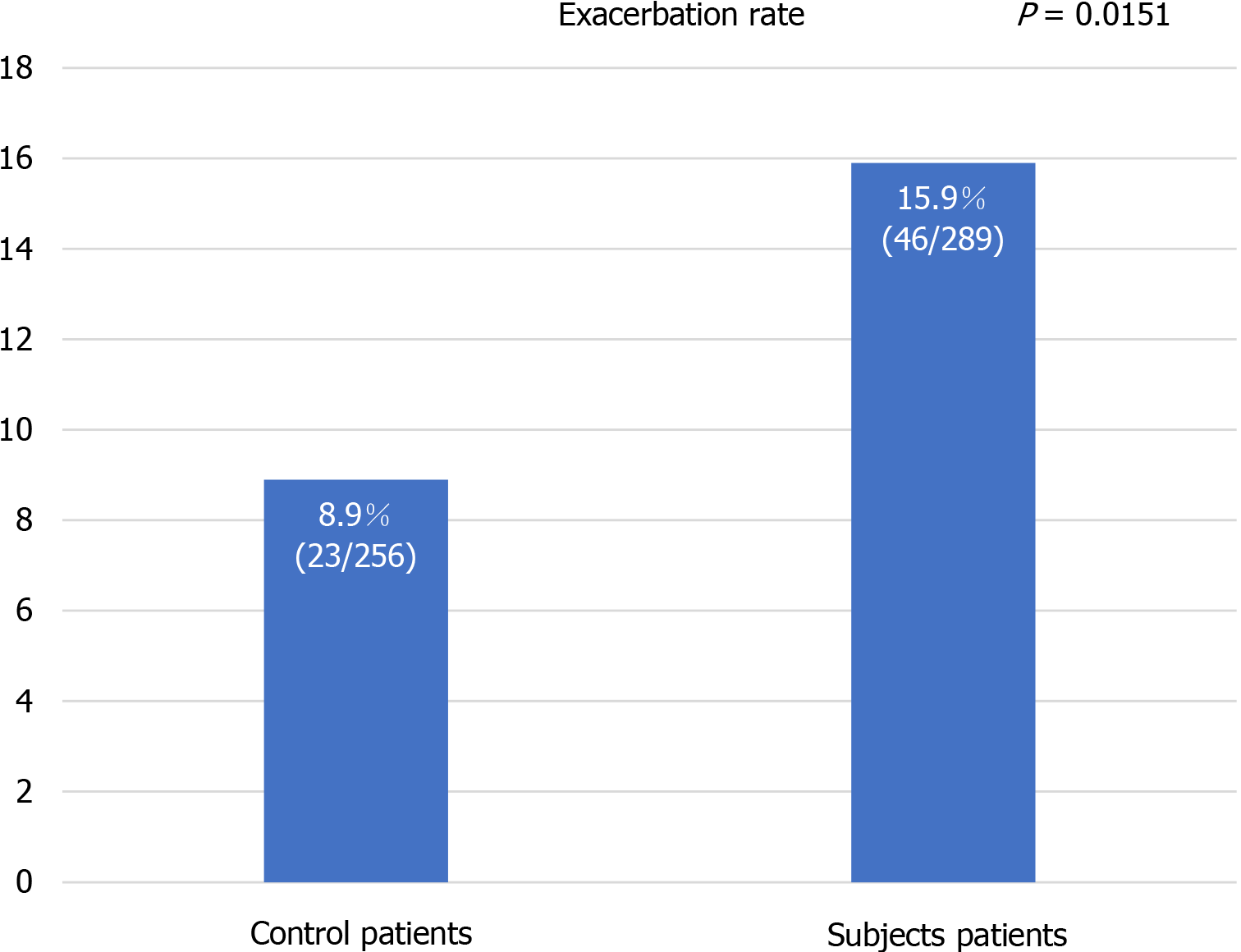

No significant differences in patient characteristics or pharmacotherapies before entry were seen between the groups. Mean UC-DAI score was significantly higher in subjects during the first wave of COVID-19 (0.67 + 0.07) compared to the previous visit (0.26 + 0.04; P = 0.0000). The exacerbation rate was significantly increased during the first wave of COVID-19, as compared with the previous year (15.9% [46/289] vs 8.9% [23/256]; P = 0.0151).

This study demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic caused exacerbations in UC patients, probably through psychological and physical stress.

Core Tip: Previous reports have suggested that physical and mental stress can exacerbate ulcerative colitis (UC). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused anxiety and stress due to severe restrictions on economic and social activities. We demonstrated, for the first time, that the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic induced UC exacerbations. Preventive treatments such as increased 5-ASA or local administration may be preferable in situations predicted to be stressful such as pandemics.

- Citation: Suda T, Takahashi M, Katayama Y, Tamano M. COVID-19 pandemic and exacerbation of ulcerative colitis. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(36): 11220-11227

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i36/11220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11220

In 2020, the global population faced an unprecedented crisis in the form of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[1]. As the number of infected patients increased, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic on March 11[2]. The number of patients also increased in Japan and the Japanese government declared a state of emergency on April 7[3]. The number of patients peaked on April 18 and then gradually decreased[4]. This was considered the first wave of COVID-19, which was followed by second and third waves after the government terminated the initial declaration. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disorder of the colonic mucosa with bloody diarrhea. The clinical course is usually unpredictable, marked by alternating periods of exacerbation and remission[5].

Many gastroenterologists and patients think that psychological and physical stress factors can exacerbate UC[6-7]. The Great East Japan Earthquake was shown to increase the risk of exacerbations among UC patients[8-9]. Stress undoubtedly contributes to disease course in UC patients. H. Engler et al[10] demonstrated the possibility that neuroendocrine regulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production such as IL-10 by peripheral blood immune cells may play roles in flares of UC patients. However, the underlying mechanisms of UC flare by stress remain unclear[10].

Besides the infection and its direct consequences, including the loss of many lives, COVID-19 was shown to bring about anxiety and stress as a result of restrictions on economic and social activities for UC patients as well as everybody else[11-12]. We therefore hypothesized that UC patients would experience serious effects from COVID-19.

This study focused on the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in a retrospective controlled study investigating the effects on exacerbations of UC among patients in Koshigaya district, a suburban area of Tokyo, Japan.

During March and April 2020, representing the period of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, a total of 289 consecutive UC outpatients in one center were enrolled in the study. All included patients regularly visited the clinic. Patients who visited for the first time after exacerbation of symptoms were excluded from the study. All included patients visited the clinic at least twice at entry. Only patients who visited for the first time after exacerbation of symptoms were excluded from the study.

The modified UC disease activity index (UC-DAI) was evaluated for each patient. The modified UC-DAI is defined as the total scores for stool frequency (normal, 0; 1–2 stools/d more than normal, + 1; 3–4 stools/d more than normal, + 2; > 4 stools/d more than normal, + 3), rectal bleeding (none, 0; blood visible with stool less than half the time, + 1; blood visible with stool half the time or more, + 2; passage of blood only, + 3), and physician rating of disease activity (normal, 0; mild, + 1; moderate, + 2; severe, + 3). Mucosal appearance at endoscopy was excluded from the modified UC-DAI[13]. Modified UC-DAI scores on the day of entry and at the previous visit were compared for each patient. An increase of ≥ 2 was considered to indicate exacerbation. The exacerbation rate was calculated and compared with that of 256 consecutive control patients independently included in the study from the same period of the previous year (March–April 2019) in the same manner. Modified UC-DAI scores of patients during the first wave of COVID-19 were compared with those at the previous visit.

This retrospective study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University Saitama Medical Center (approval no. 20100), and written, informed consent was obtained from all UC patients. This study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 2008 Declaration of Helsinki. All data were obtained from clinical records which were written on the day of the patient visit.

All patients provided informed consent to participate in this study and agreed to publication of the research results. The public were not involved in the design of this study.

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD. Discrete variables are presented as median and range. The Mann-Whitney U test or χ2 test was used to compare patients and control patients. The χ2 test was used to test for differences in exacerbation rates between the groups. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Characteristics (age, weight, height, smoking rate, sex, pancolitis rate, and medication before entry) were compared between patients and control patients.

No significant differences were identified between patients and controls in terms of mean age (45.0 ± 15.8 years vs 44.6 ± 15.6 years), weight (60.1 ± 11.3 kg vs 59.9 ± 11.2 kg), height (163.6 ± 8.6 cm vs 163.2 ± 8.4 cm), disease duration (11.6 ± 8.5 years vs 10.9 ± 8.2 years), smokers (23.8% vs 25.3%), sex (50.8% male vs 48.8% male), disease extent, or pancolitis rate (47.0% vs 50.1%) (Table 1).

| Subjects (n = 289) | Controls (n = 256) | Probability | |

| Age (yr) | 45.0 ± 15.8 | 44.6 ± 15.6 | 0.6911 |

| Sex (M/F) | 147/141 | 125/131 | 0.6351 |

| Height (cm) | 163.6 ± 8.6 | 163.2 ± 8.4 | 0.6679 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.1 ± 11.3 | 59.9 ± 11.2 | 0.7465 |

| Disease duration (yr) | 11.6 ± 8.5 | 10.9 ± 8.2 | 0.3227 |

| Smokers | 69 (23.8%) | 65 (25.3%) | 0.7426 |

| Disease extent | |||

| Total colitis | 136 (47.0%) | 129 (50.1%) | 0.4373 |

Pharmacotherapies before entry did not differ significantly between patients and control patients (Table 2).

| Drug | Patients (n = 289) | Controls (n = 256) |

| 5-ASA | 165 (57.0%) | 148 (57.8%) |

| AZA or | ||

| 6-MP | 35 (12.1%) | 33 (12.8%) |

| IFX | 36 (12.4%) | 34 (13.2%) |

| ADA | 26 (8.9%) | 19 (7.4%) |

| GLM | 9 (3.1%) | 8 (3.1%) |

| TFN | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| TF | 8 (2.7%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| IR | 5 (1.7%) | 6 (2.3%) |

| PSL | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| CHM | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| ND | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) |

Mean modified UC-DAI score was significantly higher in patients during the first wave of COVID-19 (0.67 + 0.07) than at the previous visit (0.26 + 0.04; P = 0.0000) (Figure 1).

Mean modified UC-DAI score during the whole pandemic period (March and April 2020) was 0.44 ± 1.04, compared with 0.26 ± 0.73 during the control period. We thus concluded that overall UC-DAI score was significantly higher during the pandemic period than during the control period (P = 0.0192).

Exacerbation during the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly more frequent in patients (46/289, 15.9%) than in control patients (23/256, 8.9%; P = 0.0151) (Figure 2).

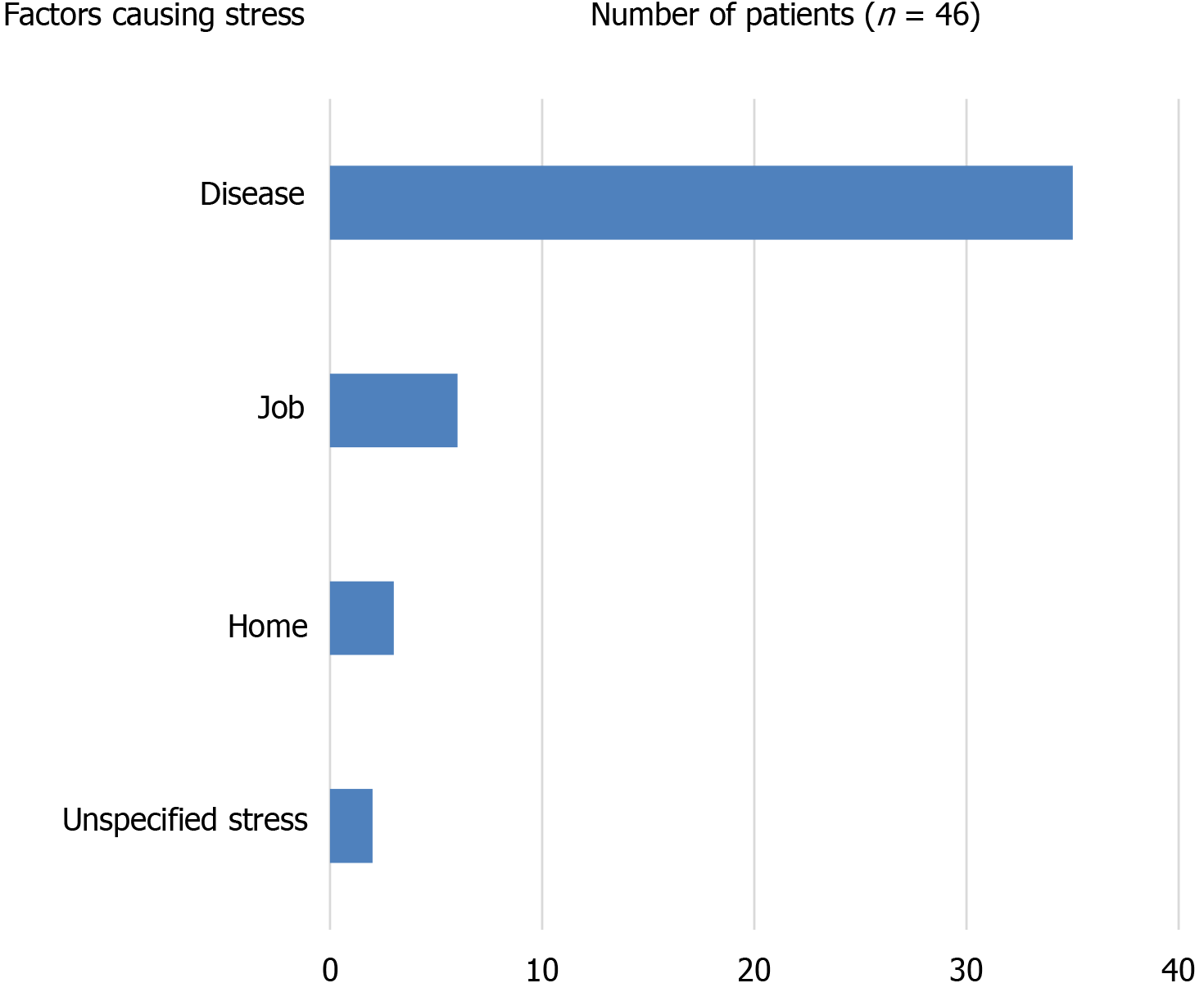

Questionnaires on stress during the pandemic revealed that among the 46 patients who experienced exacerbation during the pandemic, 35 reported stress due to the disease, 6 reported stress due to their jobs, 3 reported stress due to staying home, and 2 reported non-specific stress (Figure 3).

We demonstrated that the exacerbation rate among UC patients was significantly increased during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, as compared with controls.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) flare is induced by psychological and physical stressors[6]. Moreover, Dion et al[14] demonstrated that fresh and acute stress exerts a stronger influence than long-term or continuous stress. In Japan, right after the WHO declaration of a pandemic, the number of patients with COVID-19 increased, peaking on April 18 and gradually decreasing in April. This represented the first wave of COVID-19 in Japan[4]. Many people would have been deeply anxious about the disease during this period[15]. We therefore hypothesized that the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic would have exerted a greater influence on UC patients than the second or third waves. The stress on individuals would have been significant during this period, even among patients not actually infected with the virus. No patient included in this study developed COVID-19. We chose the time period right after the WHO declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic for this study. COVID-19 has influenced human lives in many ways. Japan has not experienced city-wide lockdowns as in European countries or the United States. However, COVID-19 has exerted significant effects on exacerbations in UC patients. As depicted in the results, the majority of patients who experienced exacerbation reported non-specific stress. However, they may well have felt unconsciously anxious or uneasy under circumstances in which nobody knew what would happen next. Trindade et al[16] demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have exerted relevant effects on psychological well-being in UC patients. In Japan, the government declared a state of emergency, but no lockdowns or curfews. However, residents were still requested to refrain from going out unnecessarily. The operation of many recreational facilities was restricted[3]. Many workers were required to work from home using the internet to reduce the risk of infection, but this resulted in mental, physical and social isolation[17]. Together with school closures, many people suffered from the compounding burdens of working at home and caring for children[18].

As we evaluated the effect of the first wave of the COVD-19 pandemic which had already taken place, our study is retrospective and it is essentially impossible to evaluate the findings of endoscopy before the first wave of the pandemic. Therefore, we used the modified UC-DAI (without endoscopic findings) instead of UC-DAI, as we described in the methods, which resulted in less subjective quality of this study. However, we set up two controls: modified UC-DAI at last visits and pairs of modified UC-DAI in the previous year, which provided our study with more subjective verifications.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic caused exacerbations in UC patients, probably through psychological and physical stress, which is new and has not been shown previously. Healthcare professionals involved in managing IBD should pay attention to the psychological responses of patients to this pandemic and of possible ramifications for disease expression.

In 2020, the global population was faced with the unprecedented crisis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Besides the infection and its consequences, COVID-19 also resulted in anxiety and stress resulting from severe restrictions on economic and social activities.

Fresh, acute stress exerts stronger influences than continuous stress on ulcerative colitis (UC) patients, presenting in forms such as exacerbation.

To determine whether this first wave had serious effects on UC patients included in a retrospective controlled study.

A total of 289 consecutive UC out-patients visited our clinic, who were included into the study, We assessed the modified UC disease activity index (UC-DAI) in each patient.

The exacerbation rate was significantly increased during the first wave of COVID-19, as compared with the previous year. Mean UC-DAI score was significantly higher in subjects during the first wave of COVID-19 than at the previous visit.

This study demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic caused exacerbations in UC patients, probably through psychological and physical stress.

Healthcare professionals involved in managing inflammatory bowel disease should pay attention to the psychological responses of patients to this pandemic and of possible ramifications for disease expression. Preventive treatment such as increased 5-ASA or local administration may be preferable in situations predicted to be stressful such as pandemics.

We would like to thank Takamiya, Aoki, Sugimoto, Suga, and Wakabayashi of Morio Clinic for preparing the patient list.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhou YJ S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan YJ. The outbreak of COVID-19: An overview. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 878] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 143.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. [cited 3 March 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19. |

| 3. | COVID-19 Information and Resources. Overview of the declaration of a state of emergency with Covid-19. [cited 7 April 2021]. Available from: https://corona.go.jp/news/news_20200421_70.html. |

| 4. | Special site of coronavirus. Number of infected people in Japan (NHK Summary). [cited 14 May 2021]. Available from: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/special/coronavirus/data-all/. |

| 5. | Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1151] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 116.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 6. | Rozich JJ, Holmer A, Singh S. Effect of Lifestyle Factors on Outcomes in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:832-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Kuroki T, Ohta A, Aoki Y, Kawasaki S, Sugimoto N, Ootani H, Tsunada S, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K. Stress maladjustment in the pathoetiology of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:522-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shiga H, Miyazawa T, Kinouchi Y, Takahashi S, Tominaga G, Takahashi H, Takagi S, Obana N, Kikuchi T, Oomori S, Nomura E, Shiraki M, Sato Y, Umemura K, Yokoyama H, Endo K, Kakuta Y, Aizawa H, Matsuura M, Kimura T, Kuroha M, Shimosegawa T. Life-event stress induced by the Great East Japan Earthquake was associated with relapse in ulcerative colitis but not Crohn's disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katayama Y, Takahashi M. Great East Japan Earthquake and exacerbation in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S-786. |

| 10. | Engler H, Elsenbruch S, Rebernik L, Köcke J, Cramer H, Schöls M, Langhorst J. Stress burden and neuroendocrine regulation of cytokine production in patients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;98:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheema M, Mitrev N, Hall L, Tiongson M, Ahlenstiel G, Kariyawasam V. Depression, anxiety and stress among patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: Australian national survey. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grunert PC, Reuken PA, Stallhofer J, Teich N, Stallmach A. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the COVID-19 Pandemic - the Patients' Perspective. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, Robinson M, Greenberger N, Saibil F, Martin T, Sparr J, Prokipchuk E, Borgen L. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1894-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wintjens DSJ, de Jong MJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, Becx MC, Maljaars JP, van Bodegraven AA, Mahmmod N, Markus T, Haans J, Masclee AAM, Winkens B, Jonkers DMAE, Pierik MJ. Novel Perceived Stress and Life Events Precede Flares of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Prospective 12-Month Follow-Up Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:410-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stickley A, Matsubayashi T, Sueki H, Ueda M. COVID-19 preventive behaviours among people with anxiety and depressive symptoms: findings from Japan. Public Health. 2020;189:91-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Trindade IA, Ferreira NB. COVID-19 Pandemic's Effects on Disease and Psychological Outcomes of People With Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Portugal: A Preliminary Research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1224-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sasaki N, Kuroda R, Tsuno K, Kawakami N. Workplace responses to COVID-19 associated with mental health and work performance of employees in Japan. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shimazu A, Nakata A, Nagata T, Arakawa Y, Kuroda S, Inamizu N, Yamamoto I. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 for general workers. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |