Published online Dec 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i35.11102

Peer-review started: July 20, 2021

First decision: September 28, 2021

Revised: October 12, 2021

Accepted: October 27, 2021

Article in press: October 27, 2021

Published online: December 16, 2021

Processing time: 142 Days and 23.6 Hours

Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is considered to have a benign prognosis in terms of cardiovascular mortality. This serial case report aimed to raise awareness of ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in apical HCM.

Here we describe two rare cases of apical HCM that presented with documented VF and sudden cardiac collapse. These patients were previously not recom

These cases illustrate serious complications including VF and aborted sudden cardiac arrest in apical HCM patients who are initially not candidates for primary prevention using ICD implantation based on current guidelines.

Core Tip: Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a rare form of non-obstructive HCM. It has a benign prognosis in terms of cardiovascular mortality. Here we describe two rare cases of apical HCM that presented as documented ventricular fibrillation (VF) and sudden cardiac collapse. Although apical HCM has a typically benign prognosis, clinicians must consider that VF can occur and lead to sudden cardiac arrest.

- Citation: Park YM, Jang AY, Chung WJ, Han SH, Semsarian C, Choi IS. Ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac arrest in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Two case reports . World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(35): 11102-11107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i35/11102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i35.11102

Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is considered clinically benign, with an estimated annual mortality rate of 0-0.1% and no reports of sudden cardiac death (SCD) during follow-up[1]. Case reports of patients developing ventricular tachycardia (VT), mainly due to an apical aneurysmal segment and sudden cardiac collapse, have been reported[2,3]. However, documented ventricular fibrillation (VF) with sudden cardiac arrest without apical aneurysm is extremely rare in patients with apical HCM.

Here we report two cases of apical HCM who presented with documented VF and sudden cardiac collapse who were previously not candidates for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy based on current guidelines.

Case 1: A 41-year-old man was brought to the emergency department after sudden cardiac collapse.

Case 2: A 29-year-old man was brought to the emergency department after sudden cardiac collapse.

Case 1: The patient had known apical HCM; however, he did not receive regular follow-up or management. He presented to the emergency department after sudden cardiac collapse during sleep.

Case 2: The patient had known apical HCM, and he had received regular follow-up at the cardiology department for apical HCM and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) over the preceding 5 years. He was brought to the emergency department after sudden cardiac collapse while working.

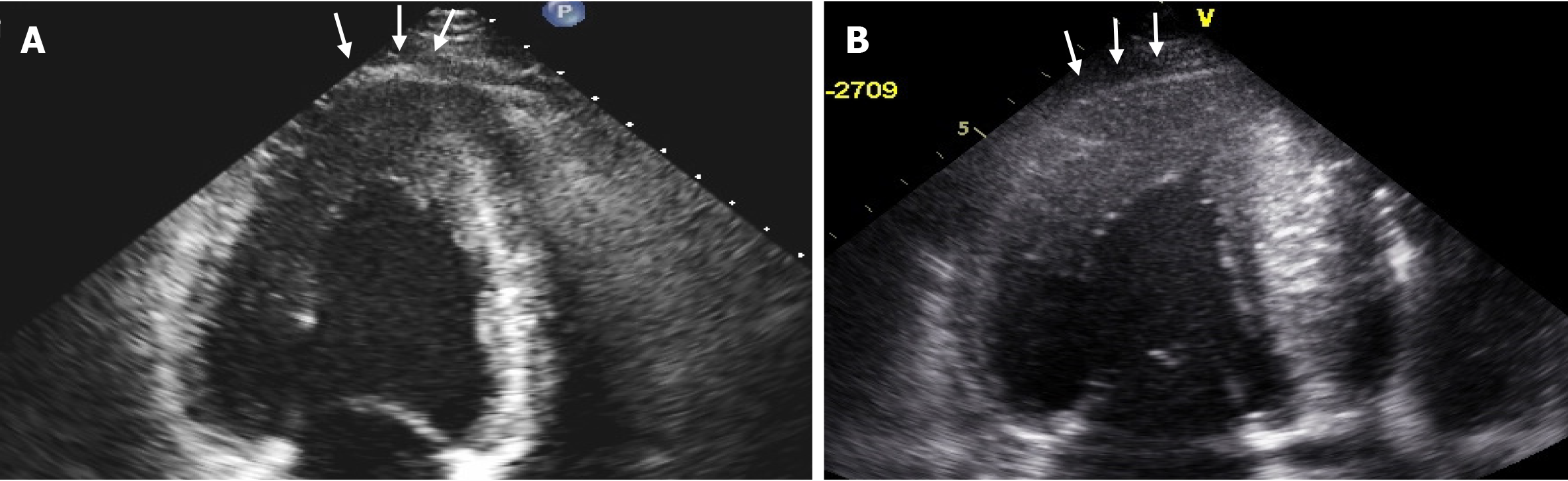

Case 1: The patient visited the cardiology outpatient department with palpitations and chest discomfort 3 years prior. Echocardiography at that time revealed apical HCM (18.7 mm thickness at the apex) with a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF; 58%) and diastolic relaxation impairment with an elevated e/e′ ratio of 22 and enlarged left atrium (51 mm) (Figure 1A). Holter monitoring did not demonstrate relevant arrhythmia, and no paradoxical blood pressure response was observed during the exercise tolerance test at that time. He was prescribed a β-blocker; however, the patient did not complete follow-up.

Case 2: The patient was diagnosed with apical HCM and paroxysmal AF 5 years prior when he presented with chest discomfort. Echocardiography revealed apical HCM (20.1 mm thickness at the apex) without apical aneurysm and a normal LVEF (59%) and a diastolic relaxation impairment with an elevated e/e′ ratio of 16 and an enlarged left atrium (57 mm) (Figure 1B). Over the preceding 5 years, he had received regular follow-up at the cardiology department and was treated with aspirin and amiodarone.

Cases 1 and 2: Family history was unremarkable for structural heart disease, syncope, or SCD.

Cases 1 and 2: On admission, the patients were unconscious and pulseless.

Case 1: The patient’s troponin I level (0.36 mg/mL) was within the normal range, while the CK-MB level (23.42 ng/mL) was remarkably elevated. His electrolyte levels were within the normal ranges.

Case 2: Troponin I level (1.78 mg/mL) and CK-MB level (9.77 ng/mL) were slightly elevated. His electrolyte levels were within the normal ranges.

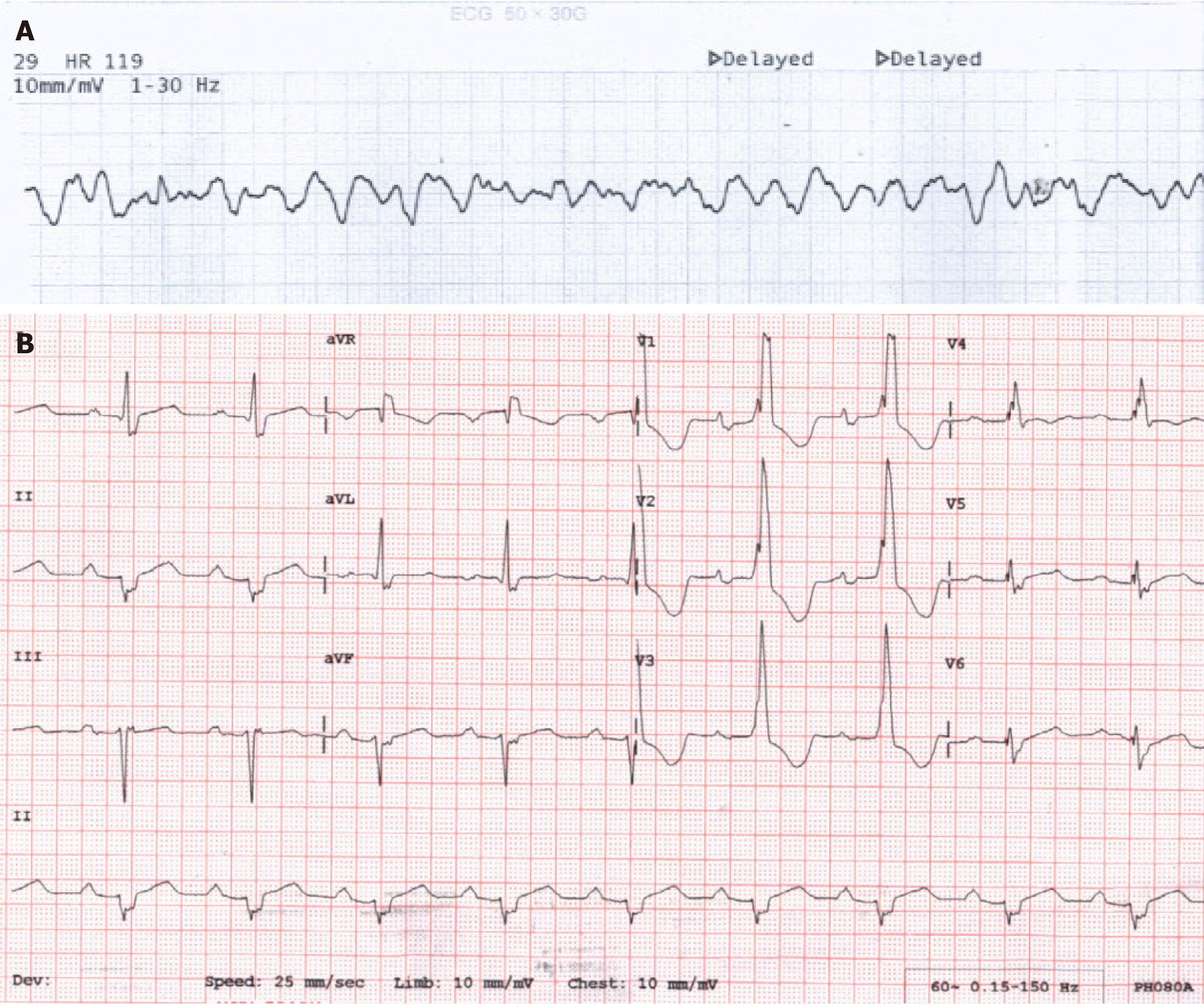

Case 1: Initial electrocardiography (ECG) revealed VF (Figure 2A). Biphasic 200-J defibrillation restored sinus rhythm, and his cardiopulmonary function recovered without neurologic sequelae. ECG performed after stabilization showed sinus rhythm with deep T-wave inversion (Figure 2B). Coronary angiography revealed no significant stenosis in the epicardial coronary arteries.

Case 2: Initial ECG revealed VF (Figure 3A). Biphasic 150-J defibrillation restored sinus rhythm, and his cardiopulmonary function recovered without neurologic sequelae. His ECG after stabilization was similar to that before the cardiac collapse, showing sinus rhythm with a tri-fascicular block and T-wave inversion (Figure 3B). Coronary angiography revealed no significant stenosis in the epicardial coronary arteries.

Cases 1 and 2: The final diagnosis was VF and aborted sudden cardiac arrest in the apical HCM.

Case 1: The patient was treated with carvedilol 6.25 mg twice daily and underwent ICD implantation for the secondary prevention of SCD.

Case 2: The patient underwent ICD implantation for the secondary prevention of SCD while maintaining his current medications.

Case 1: The patient was discharged uneventfully and remained free of VF for 3 years.

Case 2: The patient was subsequently discharged uneventfully. He experienced an inappropriate shock due to paroxysmal AF; however, he has remained free of VF for 10 years.

Apical HCM is considered clinically benign with an estimated annual mortality rate of 0-0.1% with no reports of SCD during follow-up[1]. Case reports have detailed patients developing VT mainly due to an apical aneurysmal segment and sudden cardiac collapse[2-5]. However, documented VF with sudden cardiac arrest without apical aneurysm is extremely rare in patients with apical HCM.

ICD implantation is recommended in HCM patients at high risk of SCD based on current guidelines[6,7]. Neither of our patients had any established risk factors, risk modifiers, or high-risk features. Neither met the criteria for ICD implantation according to the current guidelines. However, VF and sudden cardiac arrest occurred later despite the apical HCM, which is known to be clinically benign.

Although the risk factors for VF and SCD in apical HCM are rarely evaluated because of its significantly low incidence, several parameters affecting poor outcomes were reported previously. Patients of advanced age with hypertension, diabetes, or baseline AF have poor prognosis or decreased survival[2,8]. Patients with apical HCM and poor clinical outcomes have more advanced diastolic dysfunction, increased left atrial volume, reduced myocardial contraction/relaxation properties, and increased LV filling pressure at presentation[2]. Impaired LV diastolic function is a proposed mechanism for progressive left atrial enlargement and subsequent AF development[1,9]. Apical aneurysm and late gadolinium enhancement extent on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also independent predictors of a poor outcome[10]. However, the association between VF and these parameters has not been evaluated until now.

The hypertrophied LV apex could predispose the myocardium to ischemia due to a limited coronary blood flow reserve. The foci of cellular disarray throughout the hypertrophied LV wall might impair the transmission of normal electrophysiological impulses and predispose that region to a disordered pattern of depolarization and repolarization, thereby serving as an arrhythmogenic substrate[11]. Our second patient had a trifascicular block and inverted T-waves on ECG in addition to LV hypertrophy prior to VF development. These findings indicate that adverse electrical remodeling had already progressed in the myocardium and may have predisposed the patient to developing VF.

Although apical HCM has a typically benign prognosis, VF can occur and lead to sudden cardiac arrest. Our case reports support the concept that clinical outcomes in patients with apical HCM are not always as benign as previously thought. We should be aware of serious complications, including VF, and aborted sudden cardiac arrest in apical HCM patients who are initially not candidates for primary prevention ICD implantation based on current guidelines. Risk factors such as diastolic dysfunction, late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac MRI, or electrical remodeling on ECG should be evaluated further for risk stratification for VF and SCD in cases of apical HCM.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Korean Society of Cardiology; Korean Heart Rhythm Society; and Asian Pacific Heart Rhythm Society.

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Payus AO S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, Rakowski P, Parker TG, Wigle ED, Rakowski H. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:638-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Klarich KW, Attenhofer Jost CH, Binder J, Connolly HM, Scott CG, Freeman WK, Ackerman MJ, Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ, Ommen SR. Risk of death in long-term follow-up of patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1784-1791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chung T, Yiannikas J, Freedman SB, Kritharides L. Unusual features of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:879-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sanghvi NK, Tracy CM. Sustained ventricular tachycardia in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, midcavitary obstruction, and apical aneurysm. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30:799-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park JS, Choi Y. Stereotactic Cardiac Radiation to Control Ventricular Tachycardia and Fibrillation Storm in a Patient with Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy at Burnout Stage: Case Report. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernandez-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding C, Van Veldhuisen DJ; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2447] [Cited by in RCA: 2646] [Article Influence: 264.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, Deal BJ, Dickfeld T, Field ME, Fonarow GC, Gillis AM, Granger CB, Hammill SC, Hlatky MA, Joglar JA, Kay GN, Matlock DD, Myerburg RJ, Page RL. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:e73-e189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arad M, Penas-Lado M, Monserrat L, Maron BJ, Sherrid M, Ho CY, Barr S, Karim A, Olson TM, Kamisago M, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Gene mutations in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:2805-2811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamaguchi H, Ishimura T, Nishiyama S, Nagasaki F, Nakanishi S, Takatsu F, Nishijo T, Umeda T, Machii K. Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy with giant negative T waves (apical hypertrophy): ventriculographic and echocardiographic features in 30 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44:401-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hanneman K, Crean AM, Williams L, Moshonov H, James S, Jiménez-Juan L, Gruner C, Sparrow P, Rakowski H, Nguyen ET. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging findings predict major adverse events in apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Imaging. 2014;29:331-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1997;350:127-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |