Published online Dec 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10652

Peer-review started: February 9, 2021

First decision: April 25, 2021

Revised: May 27, 2021

Accepted: October 20, 2021

Article in press: October 20, 2021

Published online: December 6, 2021

Processing time: 293 Days and 18.1 Hours

The treatment of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) has progressed little in recent years because of its unique biological activities and complex genomic alterations. Chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy has been widely accepted as the first-line treatment for SCLC.

Here, we present a 68-year-old male smoker who was diagnosed with SCLC of the right lung. After several cycles of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the tumor progressed with broad metastasis to liver and bone. Histopathological examination showed an obvious transformation to adenocarcinoma, probably a partial recurrence mediated by the chemotherapy-based regimen. A mixed tumor as the primary lesion and transformation from SCLC or/and tumor stem cells may have accounted for the pathology conversion. We adjusted the treatment schedule in accord with the change in phenotype.

Although diffuse skeletal and hepatic metastases were seen on a recent computed tomography scan, the patient is alive, with intervals of progression and shrinkage of his cancer.

Core Tip: In this report, we present a male patient with a diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) who developed metastatic adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-SCLC, after standard chemotherapy regimens. He has survived for 90 mo since the first diagnosis, which is longer than expected.

- Citation: Ju Q, Wu YT, Zhang Y, Yang WH, Zhao CL, Zhang J. Histology transformation-mediated pathological atypism in small-cell lung cancer within the presence of chemotherapy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(34): 10652-10658

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i34/10652.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i34.10652

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) is a subtype of lung cancer because of its histology and morphology, and it accounts for 15%-20% of newly diagnosed cases worldwide every year[1]. Owing to its rapid growth and progression, it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage by histopathological examination, indicating a life expectancy of less than 1 year. As for treatment, there is a consensus that normative chemotherapy and appropriate-dose radiotherapy lead to high response rate in a clinical pathology selection-dependent manner that is recommended by American Society of Clinical Oncology[2,3]. It should be noted that targeted therapy and immunotherapy, which are likely to be effective in the treatment of non-SCLC (NSCLC)[4], are not recom

A 68-year-old man with a smoking history of 40 pack-years came to seek medical advice in light of cough, expectoration, and shortness of breath.

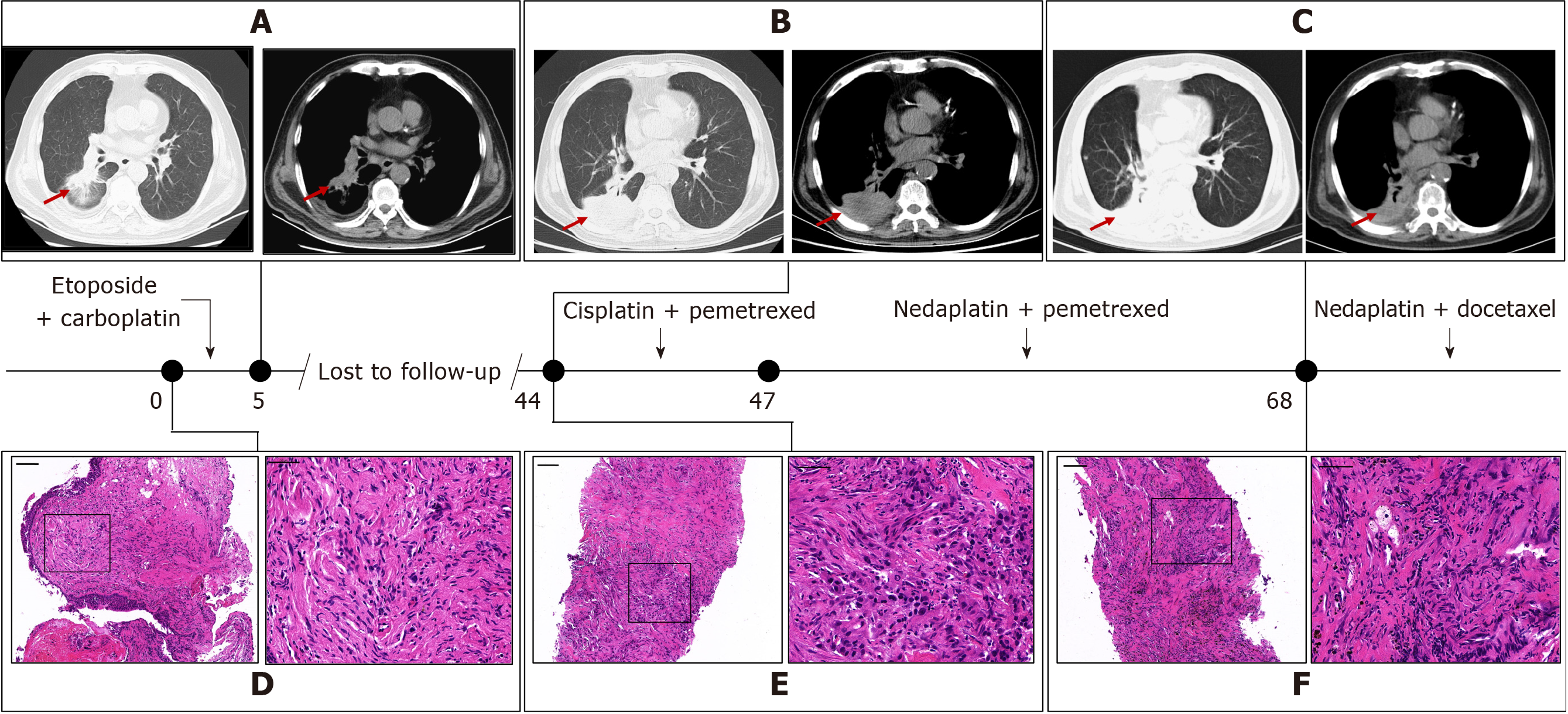

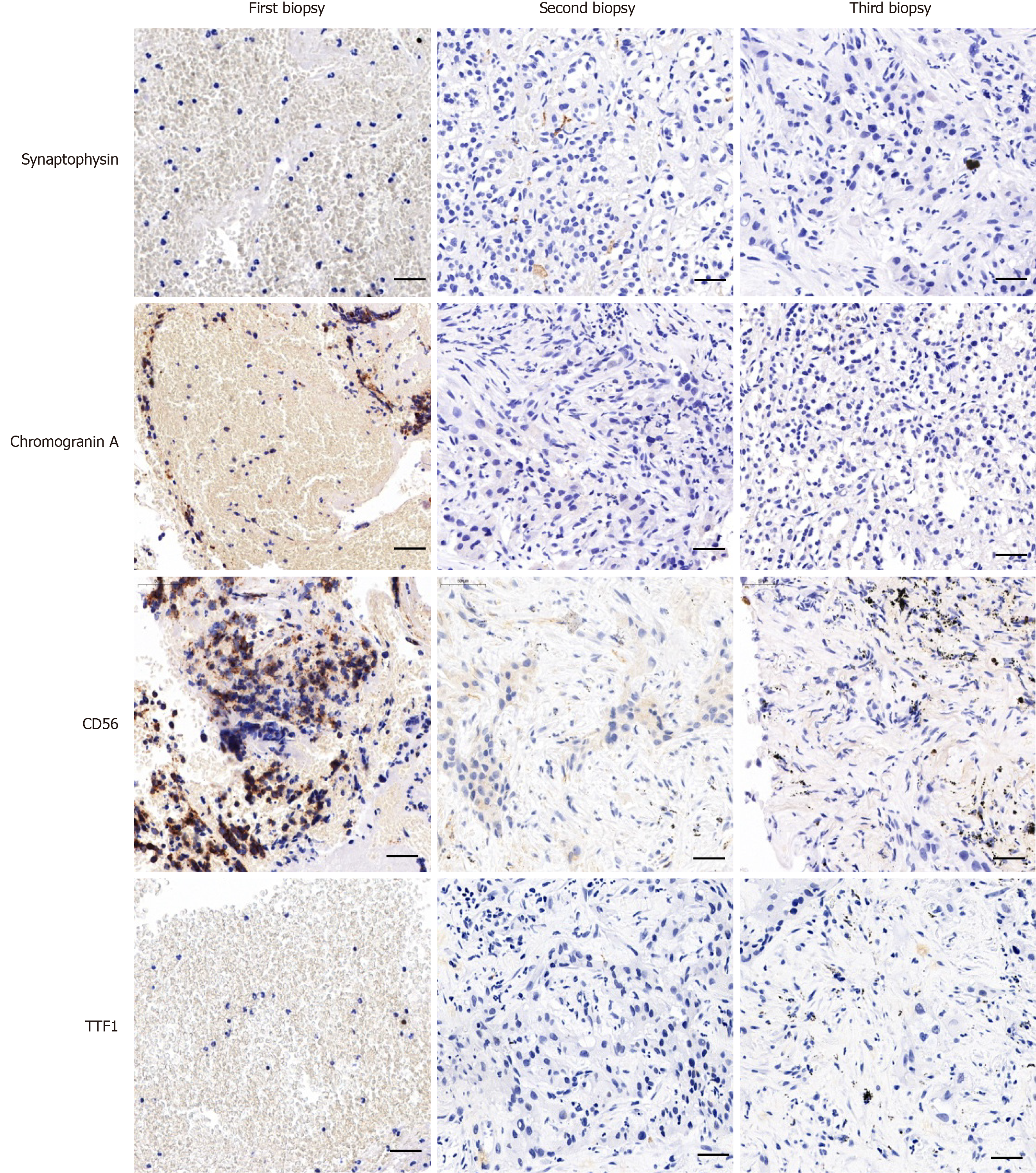

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest (which cannot be found at present) indicated a malignant tumor of the lung. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy confirmed the lesion characteristics and histopathology. At high magnification, cells in two biopsy samples of same lesion were uniform in size and arrangement, fusiform in shape with hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1D), and having an aggressive growth pattern. Coupled with immunohistochemistry (IHC), these results indicated a SCLC diagnosis (Figure 2). Molecular pathology was tested by amplification-refractory mutation system (ARMS)-PCR, which indicated an absence of sensitive mutation (Supplementary Figure 1A). According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the American College of Chest physicians guidelines, the patient was treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy consisting of six cycles of etoposide and carboplatin with thoracic radiotherapy Dt45Gy/30F twice per day. After treat, his clinical symptoms improved and the lesion in the right lower lobe shrank dramatically on CT scanning (Figure 1A).

The patient suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and diabetes for at least 10 years. As they were not thought to be associated with the progression of lung cancer, we did not include a detailed description in this article.

The presence of bilateral pulmonary interstitial hyperplasia and inhomogeneous emphysema were consistent with tumor progression and deterioration of the patient’s condition. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsies were performed to determine the reason why the standard SCLC treatment did not have a curative effect. The tumor cells were ovoid with hyperchromatic nuclei and arranged in strips or nests (Figure 1E). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) indicated poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma owing to the presence of some specific pathological markers (Figure 2). What needed more attention was that several SCLC markers, such as thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1, cytokeratin (CK)5/6, and P40, were expressed only in individual cells, and Ki-67-positive cells accounted for more than 25%, indicating rapid growth and proliferation of tumor cells. Genetic analysis found that the patient had no epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement (D5F3 Ventana IHC). However, repeated molecular pathology showed that after standard chemotherapy, the patient bore a KRAS mutation (Supplementary Figure 1B), which corresponded with the histology findings. Four cycles of cisplatin and pemetrexed achieved a decrease in the size of the lesion in the right lower lung, which further supported the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

With the remission of clinical symptoms, the patient failed to continue regular follow-up and periodic imaging. It was beyond our expectation that the patient suffered thoracalgia in the lower right chest 3 years after the last CT examination. A CT examination of his chest indicated growth and consolidation of the lesion in the lower right lung, with scattered nodules, and right inferior lobe insufficiency compared with a CT obtained 3 years previously. (Figure 1B).

Advanced lung cancer.

After the patient stopped treatment, he experienced persistent dull pain in the right hypochondriac region and back with no noticeable improvement after odynolysis. Follow-up imaging revealed that the parietal pleura were eroded by invasive malignant cells, and that there was a strong possibility that tumor cells had invaded bone, brain, liver, and local and distant lymph nodes. According to the patient’s condition and his tolerance of chemotherapeutic drugs, nedaplatin plus pemetrexed, together with intermittent local radiation, were seen as the best treatment choice. After several cycles, the clinical manifestations were improved. However, after a 4 mo interval, CT revealed that the solid pulmonary nodules in the right lung had enlarged, pleural effusion had emerged in the right thoracic cavity, and a nodule embedded in upper lobe of the left lung had progressed, all of which indicated tumor progression (Figure 1C). A third ultrasound-guided biopsy of the same nodules in the right lung found large cells with hyperchromatic nuclei arranged as in an adenoma, and with aggressive characteristics (Figure 1F). IHC staining and molecular examination supported the previous diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the lung (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1C). Combination treatment with nedaplatin and pemetrexed were continued for two cycles, until the patient reported the appearance of blood in the phlegm.

Subsequently, pemetrexed was substituted for docetaxel in previous therapeutic schedule in several cycles to now. At this time, the patient is alive 76 mo after the definitive diagnosis.

It is well known that SCLC accounts for a small proportion of newly diagnosed lung cancer worldwide every year. The incidence is the highest in male and female smokers, and SCLC has a high mortality less than 1 year after diagnosis[1]. On the basis of the location of the lesion and distant metastasis, SCLCs are generally staged as limited and extensive disease, which have different prognoses and treatment schedules. Its characteristic rapid progression and late diagnosis as metastatic disease determine its poor prognosis, with a median survival of 3 mo in untreated patients. A high response rate and sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy make it possible to alleviate SCLC to some extent, but lead to relapse within the first year after chemoradiotherapy[6].

Even though genome-based diagnosis has increased the options for targeted therapy for NSCLC patients, SCLC treatment options remain limited to regimens based on chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In addition, therapeutic effectiveness varies with the patient’s condition, drug dose and frequency, and the quantity of radiation. It is noteworthy that, compared with NSCLC, biomolecular aberrations such as mutations of EGFR, KRAS and BRAF genes or ALK gene rearrangements are rare in SCLC, which leads to a lack of indications for the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors7]. Instead, mutations of genes involved in p53 and RB and deletions or increased copy number in specific chromosomes contribute to carcinogenesis, and few effective, targeted drugs are available[8]. Surprisingly, a recent study reported that atezolizumab, a programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor of immunotherapeutic drugs, combined with etoposide and carboplatin extended overall survival of SCLC patients and has been approved as first-line treatment of advanced-stage SCLC, indicating the feasibility of immunotherapy to extend the life expectancy of SCLC patients[9].

In this case, the biopsy had SCLC characteristics, and the patient received several cycles of combination treatment with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. A second biopsy of the same lesion was found to be adenocarcinoma of lung cancer. Other than improper procedures and ineluctable errors in drawing samples, there are several explanations for this phenomenon. (1) The first involves mixed types of lung cancer at the initial diagnosis. After combined treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, the dominant SCLC component was suppressed or eliminated, leading to development of the adenocarcinoma component. Although both are sensitive to platinum-based drugs, SCLC is more vulnerable to chemotherapy compared with other types of lung cancer. However, the first histological examination revealed no significant expression of adenocarcinoma-related biomarkers in either of two samples from the same lesion. Furthermore, comparison of the two biopsies found that there were indeed different types of lung cancer in the same lesion, which excludes mixed tumors in this case; (2) The second explanation is histopathological transformation from SCLC to NSCLC. It has been widely reported that transformation from EGFR-mutated NSCLC to SCLC while using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is a potential mechanism to mediate resistance to targeted drugs[8]. Histological transformation in SCLC is rarely reported, however. Three biopsies were obtained from this patient, and IHC staining and molecular pathology revealed changes in particular biomarkers that indicated histological transformation of the lung cancer. Moreover, switching the treatment regimen based on the histopathological results alleviated the clinical manifestations, which further supported our previous diagnosis; and (3) The third is tumor stem-cell oriented adenocarcinoma. Tumor stem cells are liable to be stimulated in particular circumstances, leading to differentiation, proliferation, and the formation of lesions[10,11]. However, given that the number of stem cells is limited and the methods of detection are not well advanced, tumor stem-cell oriented adenocarcinoma should also be taken into account. In this patient, repeated biopsies indicated a possibility that he experienced an SCLC-NSCLC transformation, mainly because of pathology-oriented diagnosis and variable characteristics on CT scans. Although a rational diagnosis of histological transformation is not possible without surgical samples, it is seemly proper to take transformation into account after excluding other underlying possibilities. Further verification is needed.

Our experience with this case highlights several key points that are critical for clinical diagnosis and treatment. The first is the necessity for several ultrasound- or CT-guided biopsies. Repeated biopsies dynamically monitor phenotypic alterations of tumor cells, which facilitates the use of appropriate treatment regimens. Secondly, sampling multiple sites in primary and metastatic organs contributes to increased accuracy of diagnosis, avoiding the limitation of single site. In this patient, samples at different lesions in first biopsy helped to determine the presence of a mixed tumor or only one type of tumor cell. Thirdly, genetic analysis or DNA sequencing help physicians to diagnose pathology, select the best treatment schedule, and assess patient prognosis. Somatic mutations in several oncogenes, including EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and others, drive abnormal proliferation of mutant cells that can be targeted by TKIs, even though the mutations are rare in SCLC. Detecting mutations is conducive to discovering histological transformation and expanding therapeutic alternatives. Finally, the implementation of standard diagnostic and therapeutic programs is important to inhibit the development of malignant lesions and further improve healing.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kupeli S S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55666] [Article Influence: 7952.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Rudin CM, Ismaila N, Hann CL, Malhotra N, Movsas B, Norris K, Pietanza MC, Ramalingam SS, Turrisi AT 3rd, Giaccone G. Treatment of Small-Cell Lung Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the American College of Chest Physicians Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4106-4111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman J, Chirieac LR, D'Amico TA, DeCamp MM, Dilling TJ, Dobelbower M, Doebele RC, Govindan R, Gubens MA, Hennon M, Horn L, Komaki R, Lackner RP, Lanuti M, Leal TA, Leisch LJ, Lilenbaum R, Lin J, Loo BW Jr, Martins R, Otterson GA, Reckamp K, Riely GJ, Schild SE, Shapiro TA, Stevenson J, Swanson SJ, Tauer K, Yang SC, Gregory K, Hughes M. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 5.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:504-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 677] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 118.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shroff GS, de Groot PM, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Truong MT, Carter BW. Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2018;56:485-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lo Russo G, Macerelli M, Platania M, Zilembo N, Vitali M, Signorelli D, Proto C, Ganzinelli M, Gallucci R, Agustoni F, Fasola G, de Braud F, Garassino MC. Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Clinical Management and Unmet Needs New Perspectives for an Old Problem. Curr Drug Targets. 2017;18:341-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kalemkerian GP, Loo BW, Akerley W, Attia A, Bassetti M, Boumber Y, Decker R, Dobelbower MC, Dowlati A, Downey RJ, Florsheim C, Ganti AKP, Grecula JC, Gubens MA, Hann CL, Hayman JA, Heist RS, Koczywas M, Merritt RE, Mohindra N, Molina J, Moran CA, Morgensztern D, Pokharel S, Portnoy DC, Rhodes D, Rusthoven C, Sands J, Santana-Davila R, Williams CC, Hoffmann KG, Hughes M. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:1171-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ross JS, Wang K, Elkadi OR, Tarasen A, Foulke L, Sheehan CE, Otto GA, Palmer G, Yelensky R, Lipson D, Chmielecki J, Ali SM, Elvin J, Morosini D, Miller VA, Stephens PJ. Next-generation sequencing reveals frequent consistent genomic alterations in small cell undifferentiated lung cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:772-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oser MG, Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, Engelman JA. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e165-e172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 717] [Article Influence: 71.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, Huemer F, Losonczy G, Johnson ML, Nishio M, Reck M, Mok T, Lam S, Shames DS, Liu J, Ding B, Lopez-Chavez A, Kabbinavar F, Lin W, Sandler A, Liu SV; IMpower133 Study Group. First-Line Atezolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Extensive-Stage Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2220-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1567] [Cited by in RCA: 2354] [Article Influence: 336.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Qian H, Shao G, Lu X, Chen Q, Sun X, Chen D, Yin R, Zhu H, Shao Q, Xu W. Stemness and inducing differentiation of small cell lung cancer NCI-H446 cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Banks-Schlegel SP, Gazdar AF, Harris CC. Intermediate filament and cross-linked envelope expression in human lung tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1187-1197. [PubMed] |