Published online Nov 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10382

Peer-review started: July 11, 2021

First decision: July 26, 2021

Revised: August 8, 2021

Accepted: September 8, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Published online: November 26, 2021

Processing time: 133 Days and 14.4 Hours

Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents were the first biologic therapy approved for the management of Crohn's disease (CD). Heart failure (HF) is a rare but potential adverse effect of these medications. The objective of this report is to describe a patient with CD who developed HF after the use of infliximab.

A 50-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and diabetes presented with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Colonoscopy and enterotomography showed ulcerations, areas of stenosis and dilation in the terminal ileum, and thickening of the intestinal wall. The patient underwent ileocolectomy and the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of stenosing CD. The patient started infliximab and azathioprine treatment to prevent post-surgical recurrence. At 6 mo after initiating infliximab therapy, the patient complained of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea that gradually worsened. Echocardiography revealed biventricular dysfunction, moderate cardiac insufficiency, an ejection fraction of 36%, and moderate pericardial effusion, consistent with HF. The cardiac disease was considered an infliximab adverse effect and the drug was discontinued. The patient received treatment with diuretics for HF and showed improvement of symptoms and cardiac function. Currently, the patient is using anti-interleukin for CD and is asymptomatic.

This reported case supports the need to investigate risk factors for HF in inflammatory bowel disease patients and to consider the risk-benefit of introducing infliximab therapy in such patients presenting with HF risk factors.

Core Tip: Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents were the first biologic therapy approved for the management of Crohn's disease (CD). While rare, heart failure (HF) is a potential adverse effect of these medications. In this report we describe a patient with CD who developed HF after treatment with infliximab. The clinical, diagnosis, imaging, and treatment details are all provided and discussed in this case report. This reported case supports the need to investigate risk factors for HF in inflammatory bowel disease patients and to consider the risk-benefit of introducing infliximab therapy in such patients presenting with HF risk factors.

- Citation: Grillo TG, Almeida LR, Beraldo RF, Marcondes MB, Queiróz DAR, da Silva DL, Quera R, Baima JP, Saad-Hossne R, Sassaki LY. Heart failure as an adverse effect of infliximab for Crohn's disease: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(33): 10382-10391

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i33/10382.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10382

Infliximab is a monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and has revolutionized the treatment of Crohn's disease (CD)[1]. Despite its effectiveness in promoting clinical and endoscopic responses[2], the medication is not free from adverse events, such as anaphylactic reactions, increased risk of infections and neoplasms such as lymphomas, appearance of autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus, and more rarely, heart failure (HF)[3,4].

HF is a clinical syndrome resulting from structural and functional cardiac abnormalities, resulting in insufficient supply of oxygen and nutrients to tissues[5]. The prevalence of HF worldwide is 23 million people[5]. The role of TNF in the pathophysiology of HF is controversial. However, Levine et al[6] demonstrated increased serum levels of TNF in patients with advanced HF and Torre-Amione et al[7] showed that TNF levels correlate with disease severity. Furthermore, clinical studies of agents that promote TNF blockade were initially promising[8-10]. However, large-scale randomized studies were discontinued as the results showed no improvement in HF or mortality[11]. Moreover, the use of infliximab is associated with worse outcomes in some HF patients, showing that TNF blockers may exacerbate or even trigger HF[12]. The current case report describes a patient with CD who manifested HF after treatment with infliximab. In addition, the current relevant literature is reviewed.

A 50-year-old woman with previous resection of the small intestine due to a stenosing CD disease, receiving treatment with infliximab, presented in the Emergency Room complaining of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

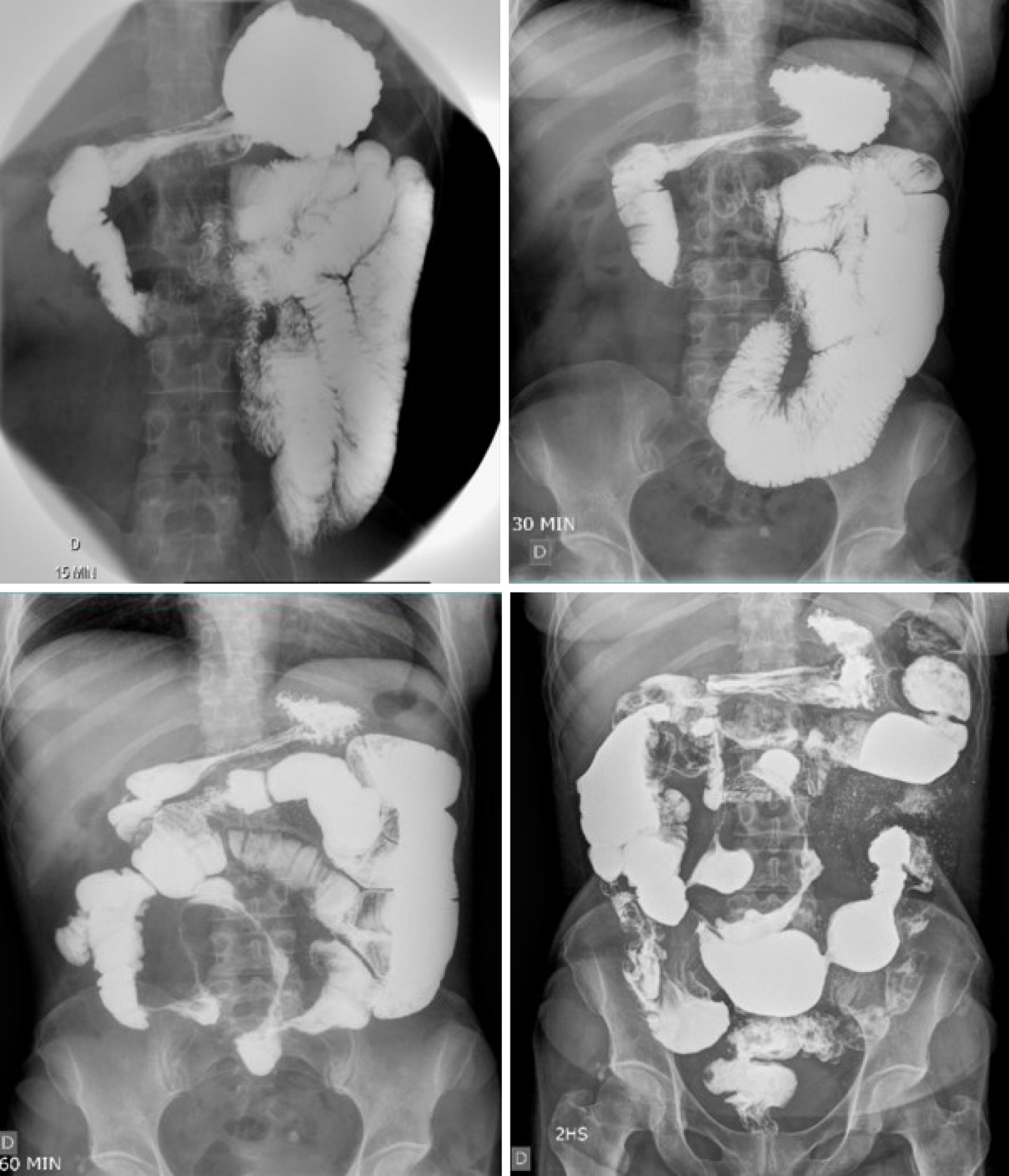

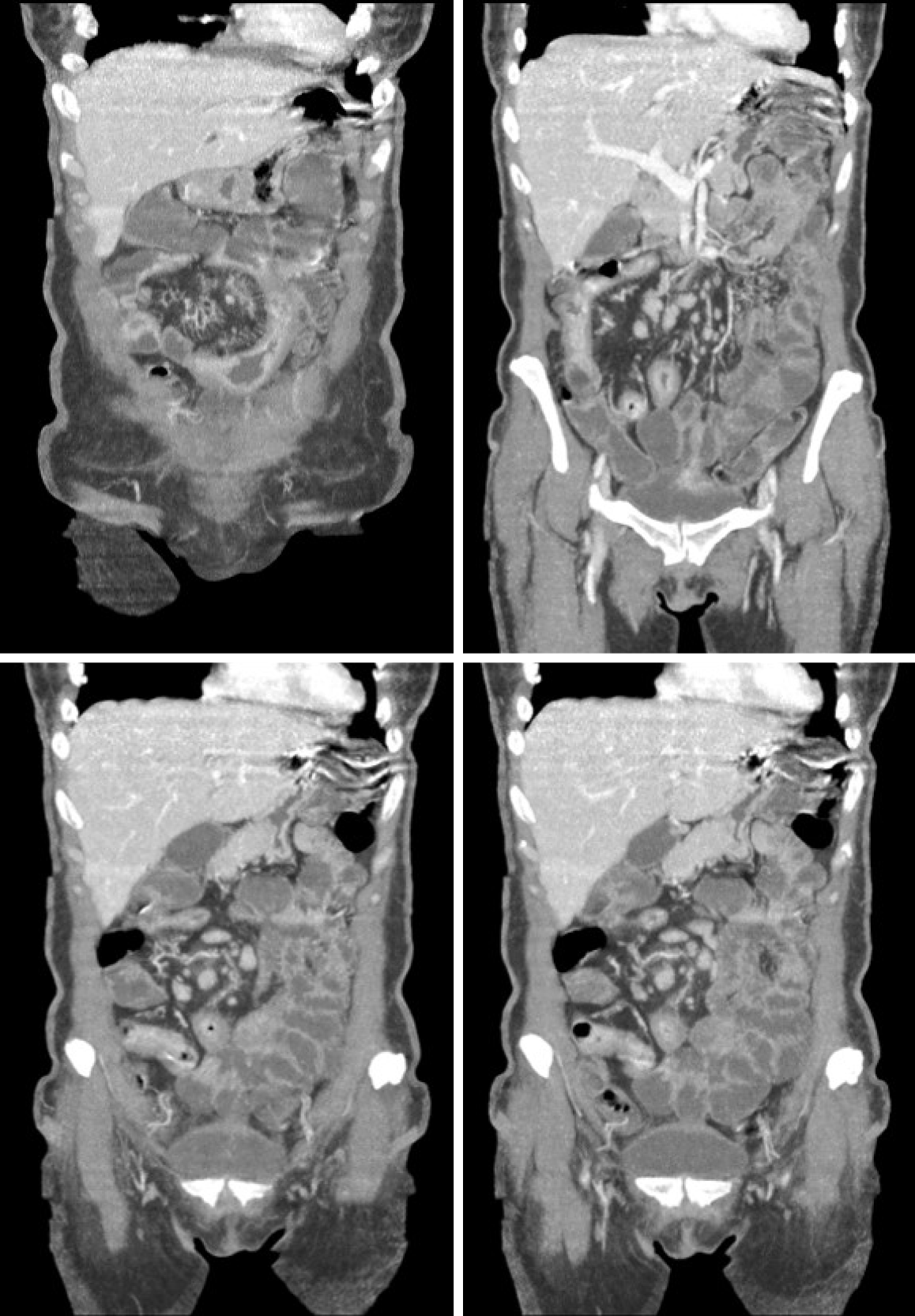

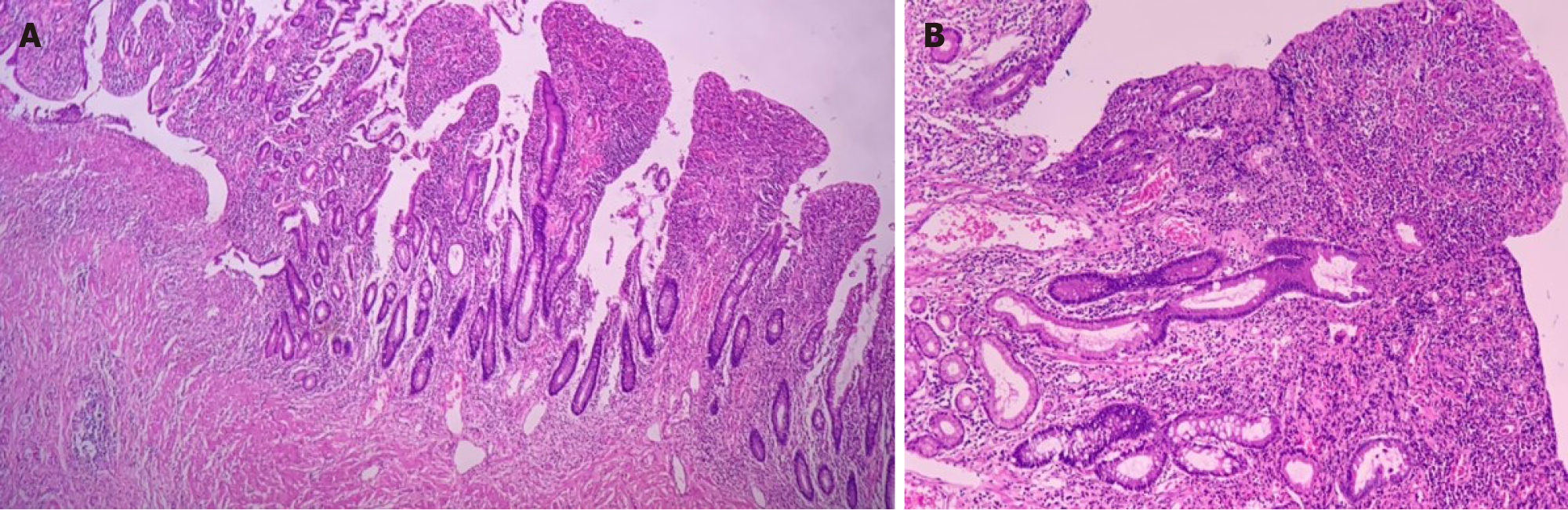

In 2016, the patient presented with diarrhea with 10 liquid bowel movements/day associated with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss of 25 kg over 6 mo. Physical examination revealed a 10-cm mass in the mesogastric region. Colonoscopy showed ulcerated stenosis of the ileocecal regions and the anatomopathological examination was consistent with nonspecific colitis with mild inflammatory activity. Abdominal ultrasound showed a segmental inflammatory process in the small intestine. Small bowel follow-through (Figure 1) and computed tomography enterography (Figure 2) showed irregularities in the mucosa consistent with ulcerations in the small intestine, stenosis and dilation in the terminal ileum, and thickening of the intestinal wall with hypervascularity of the mesentery and vascular dilatation (comb sign). Based on these clinical findings, a suspicion of small bowel CD was raised. The patient opted for an exploratory laparotomy in 2018, in which thickening of the terminal ileum was observed, and an ileocolectomy (70 cm) with ileus-ascending-anastomosis was performed (Figure 3). Anatomopathological (Figure 4) evaluation showed the presence of extensive longitudinal ulcerations, marked fibrosis of the submucosa, muscular hypertrophy, and subserous lymphoid accumulations, suggesting chronic inflammation and consistent with fibro-stenosing CD. Due to extensive resection of the small intestine and presence of residual lesions, combined treatment with infliximab (5 mg/kg) and azathioprine (2 mg/kg/d) was chosen. Colonoscopy performed 6 mo after initiation of the treatment showed four erosions in the ileocolonic anastomosis and one ulcer in the neo-terminal ileum (Rutgeerts score i2). Due to the endoscopic observed activity, the dose of infliximab was increased to 10 mg/kg. Infliximab and anti-infliximab antibody trough levels were not available. Thirty days after infliximab dose optimization, the patient complained of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. She reported the onset of mild symptoms with progressive worsening since the introduction of infliximab.

The patient presented a medical history of diabetes and arterial hypertension was treated with glibenclamide, losartan, and hydrochlorothiazide.

There was no family history.

On physical examination, the patient presented with tachypnea (26 rpm), tachycardia (116 bpm), jugular venous distension, right hypochondrial pain, hepatomegaly (3 cm), and lower limb edema.

Chest radiography showed an increase in the cardiac area. Electrocardiogram findings included sinus rhythm, signs of left atrial overload, and alteration of diffuse repolarization with strain pattern of V4-V6. Echocardiography revealed biventricular dysfunction, moderate HF, and an ejection fraction of 36%. Coronary angiography was performed, and coronary artery disease was ruled out.

The final diagnosis was HF as an adverse effect of infliximab therapy.

The infliximab was withdrawal and furosemide was prescribed. Significant improvement in symptoms was noted after 5 d of modified treatment. The patient started treatment for HF with enalapril, carvedilol, spironolactone, and amlodipine and remained asymptomatic. A new echocardiography examination showed an ejection fraction of 42%, moderate systolic dysfunction with diffuse hypokinesia, eccentric hypertrophy, significant increase of left atrium, restrictive diastolic dysfunction, mild insufficiency of aortic and tricuspid valves, and mild pulmonary arterial hypertension (42 mmHg).

After discontinuation of the anti-TNF therapy, the patient started exhibiting symptoms of CD activity, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, and weight loss. The patient then started treatment for CD with anti-IL-23 (investigational product) with significant improvement of symptoms. Currently, she has three evacuations per day with no bleeding or abdominal pain. Colonoscopy showed more than five aphthous ulcers < 5 mm each in the neo-terminal ileum without lesions in the anastomosis (Rutgeerts score i2). The patient will undergo a new colonoscopy after one year of therapy.

Treatment of CD aims for clinical and endoscopic remission and includes the use of antibiotics, steroids, immunosuppressants, and biological therapies including anti-TNF, anti-integrin, and anti-interleukin agents[13,14]. Anti-TNF agents include infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab[2] and are indicated in patients refractory or intolerant to corticosteroids, thiopurines, and methotrexate.

The choice of the drug should take into account the location, activity, and severity of the disease, response to previous therapies, presence of complications, medication efficacy, and development of side effects, in addition to the presence of extra-intestinal manifestations[13,15]. Individual patient characteristics, such as preference for route of administration, costs, and risk benefit of the drugs, should also be assessed[13,15]. In the current reported case, infliximab combined with azathioprine was chosen as the therapeutic option, taking into account access to medication and the patient's preference for intravenous administration. These drugs were provided by the state's high-cost drug dispensing program[16].

Anti-TNF agents have good long-term safety profiles[17]. Contraindications for their use include the presence of active infection, demyelinating disease, cancer, and HF [absolute in the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification NYHA III–IV and relative in NYHA II][18,19]. The patient in the current report had risk factors for the development of cardiovascular disease, such as hypertension and diabetes, but had no previous diagnosis or symptoms suggesting HF at the time that infliximab was prescribed. The patient had no previous echocardiogram. The consensus regarding the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[14,20] does not recommend screening or assessment of cardiac function before initiating anti-TNF therapy. According to the American Heart Failure guidelines[21], there is evidence supporting the use of brain natriuretic peptides (BNP) to aid in the diagnosis or exclusion of HF as a cause of symptoms. These biomarkers are increasingly being used in population screening to detect incident HF, despite not having a formal recommendation[21] or being available for use in clinical practice.

The ATTACH (Anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart failure) trial[3] evaluated the efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with moderate to severe HF (NYHA classes III and IV). The study found that symptoms worsened and concluded that short-term TNF-α antagonism did not demonstrate a benefit and was associated with greater occurrence of adverse events and mortality. Therefore, their use is not indicated under these conditions. Kwon et al[22] followed patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and CD that were treated with anti-TNF (etanercept or infliximab) and observed 47 patients who developed HF, of which 81% had no previous symptoms and 19% had worsening of preexisting symptoms. Among those who developed HF, 50% did not have risk factors, such as myocardial infarction, coronary disease, hypertension, or diabetes[22]. The average interval between the first anti-TNF infusion and diagnosis of HF was 3.5 mo (24 h to 24 mo)[22]. The mean age of the patients was 62 years[22], demonstrating that HF can manifest at any time during the use of the medication, even in patients without a diagnosis or previous symptoms. In our current case, we observed clinical and echocardiographic manifestations of HF 8 mo after the first infusion of infliximab, despite reports of symptoms beginning since the first infusion. However, the symptoms were mild and not considered by the patient after the first infusion. She only reported symptoms when they became disabling after the dose of the medication was increased.

Studies have sought to clarify the precise role of TNF-α in the regulation of cardiac function in patients with IBD, especially in the progression of HF[23]. The biological activity of TNF-α seems to be related to its serum concentration. At low levels, it induces local inflammation with the expression of adhesion molecules and stimulates the production of IL-1. At an increased level, systemic effects can be observed, such as fever, increases in acute phase reagents, cachexia, hypotension, and cardiovascular collapse[18]. Its intracellular effects occur by binding to two membrane receptors, TNF receptors 1 and 2 (TNFR1 and TNFR2)[24]. TNFR1 is expressed in most cells of the immune system and other systems, such as the heart, and mediates pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic signals[18]. In contrast, TNFR2 is found in hematopoietic and endothelial cells and is related to survival pathways[18]. There is also induction of complement-dependent and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity through the binding to transmembrane TNF expressed in cells[25]. TNF-α contributes to the progression of HF by inducing uncoupling of the β-adrenergic receptor, increasing the reaction of oxygen species formation, promoting the synthesis of nitric oxide contributing to contractile dysfunction, and increasing IL-6 and IL-1 levels, which increase myocardial dysfunction[26]. Structural changes such as reduced left ventricular function and left ventricular dilation, in addition to severe changes such as hypertrophy, apoptosis, and cardiac fibrosis, may be observed in patients with sustained TNF-α expression in the myocardium[27].

Reverse signaling is another mechanism responsible for the cardiotoxic effects of TNF-α. Transmembrane TNF produced by cardiac cells functions as a receptor for anti-TNF agents, which serves as a signal for the production of more TNF-α in the tissue and thereby increases cardiotoxicity[28,29]. Therefore, drug-induced HF should be suspected in patients who develop HF after receiving any anti-TNF therapy and discontinuation of medication is recommended in these cases[26]. In a meta-analysis conducted by Kwon et al[22], ten patients under 50 years of age who developed HF after the use of anti-TNF were evaluated. Of these patients, nine discontinued the medication, three presented complete HF resolution, six presented partial improvement, and one died. In the current case, infliximab was discontinued, and diuretic therapy was initiated for HF treatment. The patient showed improvement of symptoms and echocardiographic parameters after discontinuation of the anti-TNF; however, complete recovery of cardiac function was not achieved.

The mechanism by which infliximab causes HF in patients with CD remains uncertain. As such adverse events in populations using these medications are under-reported, it is difficult to infer a causal relationship. Attention should be paid to the recent development or exacerbation of HF in patients who have started anti-TNF therapy. Should this occur, biological therapy with another mechanism of action should be considered.

We believe that the reported patient probably had previous asymptomatic cardiac structural damage, related to presented risk factors such as diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension, characterizing stage B of AHA/ACC classification[30]. With exposure to infliximab, especially after dose optimization to 10 mg/kg, HF decom

Patients with symptomatic HF are classified as having AHA/ACC C or D stage, and their symptoms are qualified according to a symptomatic score, with NYHA being the most used score of them[30]. In patients with severe symptomatic HF NYHA III and IV, the recommendation is to avoid use of infliximab[18,19]. In patients with HF and mild symptoms (NYHA I and II), who worsen after using infliximab, it is recom

We recommend for patients in AHA/ACC stage A who are indicated to use infliximab: (1) Pre-treatment basal BNP dosage; (2) Strict control of associated comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, and coronary artery disease; (3) Close monitoring of signs and symptoms of HF after starting treatment with infliximab; and (4) Infliximab concentration monitoring and dose correction according to the therapeutic target.

The recommendations for patients in stage B of the AHA/ACC are: (1) Pretreatment echocardiography in patients with baseline BNP levels above the reference value for outpatients; (2) If echocardiography (current or previous < 5 years) is normal or with minimal change, the recommendations are the same for patients in stage A of the AHA/ACC, as detailed above; and (3) If echocardiography (current or previous) shows signs of structural and/or functional heart disease, it is recommended to start infliximab after adequate control of comorbidities, and introduction and dose adjustment of beta-blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. In addition, it is recommended to avoid other medications that potentially cause HF decompensation, use dose of 5 mg/kg for infliximab, other specialties medical monitoring, and strictly monitor signs and symptoms of HF. We also emphasize the need for further studies on this topic.

In the present case, other possible causal factors of HF have been ruled out. Chagasic myocarditis, an endemic disease in Latin America caused by infection by Trypanosoma cruzi, was ruled out by Chagas negative serology and the absence of electrocardiographic findings of the disease such as conduction disorders, low QRS voltage, arrhythmias, and changes in the QT interval[31]. Viral myocarditis is an important differential diagnosis in the face of acute HF in an immunosuppressed patient. However, the patient did not present infectious symptoms, common in this type of infection, and there was an improvement with the suspension of anti-TNF. Endomyocardial biopsy, indicated for confirmation of viral myocarditis, was not performed due to the absence of criteria for the procedure, such as the presence of ventricular arrhythmias or atrioventricular block, hemodynamic instability, or lack of therapeutic response[32]. The acute coronary syndrome was excluded through cardiac catheterization.

The reported case supports the need to investigate risk factors for HF in IBD patients and to consider the risk-benefit of introducing anti-TNF therapy in such patients presenting HF risk factors.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vasudevan A, Wen XL S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Rahier JF, Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y, Conlon C, De Munter P, D'Haens G, Domènech E, Eliakim R, Eser A, Frater J, Gassull M, Giladi M, Kaser A, Lémann M, Moreels T, Moschen A, Pollok R, Reinisch W, Schunter M, Stange EF, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Viget N, Vucelic B, Walsh A, Weiss G, Yazdanpanah Y, Zabana Y, Travis SP, Colombel JF; European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). European evidence-based Consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:47-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P; ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1585] [Cited by in RCA: 1443] [Article Influence: 180.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chung ES, Packer M, Lo KH, Fasanmade AA, Willerson JT; Anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot trial of infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure: results of the anti-TNF Therapy Against Congestive Heart Failure (ATTACH) trial. Circulation. 2003;107:3133-3140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1110] [Cited by in RCA: 1168] [Article Influence: 53.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Scheinfeld N. A comprehensive review and evaluation of the side effects of the tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:280-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stanciu AE. Cytokines in heart failure. Adv Clin Chem. 2019;93:63-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, Fillit HM, Packer M. Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1845] [Cited by in RCA: 1815] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1201-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sliwa K, Skudicky D, Candy G, Wisenbaugh T, Sareli P. Randomised investigation of effects of pentoxifylline on left-ventricular performance in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1998;351:1091-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deswal A, Bozkurt B, Seta Y, Parilti-Eiswirth S, Hayes FA, Blosch C, Mann DL. Safety and efficacy of a soluble P75 tumor necrosis factor receptor (Enbrel, etanercept) in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:3224-3226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bozkurt B, Torre-Amione G, Warren MS, Whitmore J, Soran OZ, Feldman AM, Mann DL. Results of targeted anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy with etanercept (ENBREL) in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2001;103:1044-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Louis A, Cleland JG, Crabbe S, Ford S, Thackray S, Houghton T, Clark A. Clinical Trials Update: CAPRICORN, COPERNICUS, MIRACLE, STAF, RITZ-2, RECOVER and RENAISSANCE and cachexia and cholesterol in heart failure. Highlights of the Scientific Sessions of the American College of Cardiology, 2001. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Page RL 2nd, O'Bryant CL, Cheng D, Dow TJ, Ky B, Stein CM, Spencer AP, Trupp RJ, Lindenfeld J; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committees of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Drugs That May Cause or Exacerbate Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e32-e69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn's Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 132.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, Adamina M, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gomollon F, González-Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Spinelli A, Stassen L, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Warusavitarne J, Zmora O, Fiorino G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 991] [Cited by in RCA: 896] [Article Influence: 179.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, Calabrese E, Baumgart DC, Bettenworth D, Borralho Nunes P, Burisch J, Castiglione F, Eliakim R, Ellul P, González-Lama Y, Gordon H, Halligan S, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kotze PG, Krustinš E, Laghi A, Limdi JK, Rieder F, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Tolan D, van Rheenen P, Verstockt B, Stoker J; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR]. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1242] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 191.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ministry of Health, Brazil. Crohn's Disease Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines. 2017. [cited 1 July 2021]. Available from: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Protocolos/Portaria_Conjunta_14_PCDT_Doenca_de_Crohn_28_11_2017.pdf. |

| 17. | Lin J, Ziring D, Desai S, Kim S, Wong M, Korin Y, Braun J, Reed E, Gjertson D, Singh RR. TNFalpha blockade in human diseases: an overview of efficacy and safety. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:13-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cacciapaglia F, Navarini L, Menna P, Salvatorelli E, Minotti G, Afeltra A. Cardiovascular safety of anti-TNF-alpha therapies: facts and unsettled issues. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, Annese V, Ardizzone S, Biancone L, Bortoli A, Castiglione F, D'Incà R, Gionchetti P, Kohn A, Poggioli G, Rizzello F, Vecchi M, Cottone M; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) Clinical Practice Guidelines: The use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Brazilian Study Group of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Consensus guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Arq Gastroenterol. 2010;47:313-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:776-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1130] [Cited by in RCA: 1376] [Article Influence: 172.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kwon HJ, Coté TR, Cuffe MS, Kramer JM, Braun MM. Case reports of heart failure after therapy with a tumor necrosis factor antagonist. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:807-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khanna D, McMahon M, Furst DE. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and heart failure: what have we learned and where do we go from here? Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1040-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Parameswaran N, Patial S. Tumor necrosis factor-α signaling in macrophages. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2010;20:87-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1143] [Cited by in RCA: 1058] [Article Influence: 70.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sfikakis PP. The first decade of biologic TNF antagonists in clinical practice: lessons learned, unresolved issues and future directions. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2010;11:180-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sinagra E, Perricone G, Romano C, Cottone M. Heart failure and anti tumor necrosis factor-alpha in systemic chronic inflammatory diseases. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kleinbongard P, Heusch G, Schulz R. TNFalpha in atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion and heart failure. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;127:295-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Eissner G, Kirchner S, Lindner H, Kolch W, Janosch P, Grell M, Scheurich P, Andreesen R, Holler E. Reverse signaling through transmembrane TNF confers resistance to lipopolysaccharide in human monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164:6193-6198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Juhász K, Buzás K, Duda E. Importance of reverse signaling of the TNF superfamily in immune regulation. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9:335-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147-e239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4116] [Cited by in RCA: 4650] [Article Influence: 387.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Cooper LT Jr. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1526-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 990] [Article Influence: 61.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Montera MW, Mesquita ET, Colafranceschi AS, Oliveira AC Jr, Rabischoffsky A, Ianni BM, Rochitte CE, Mady C, Mesquita CT, Azevedo CF, Bocchi EA, Saad EB, Braga FG, Fernandes F, Ramires FJ, Bacal F, Feitosa GS, Figueira HR, Souza Neto JD, Moura LA, Campos LA, Bittencourt MI, Barbosa Mde M, Moreira Mda C, Higuchi Mde L, Schwartzmann P, Rocha RM, Pereira SB, Mangini S, Martins SM, Bordignon S, Salles VA; Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. I Brazilian guidelines on myocarditis and pericarditis. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;100:1-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |