Published online Nov 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10308

Peer-review started: July 6, 2021

First decision: August 18, 2021

Revised: August 21, 2021

Accepted: September 22, 2021

Article in press: September 22, 2021

Published online: November 26, 2021

Processing time: 139 Days and 8.2 Hours

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is a human neurotropic and double-stranded DNA alpha-herpes virus. Primary infection with VZV usually occurs during childhood, manifesting as chickenpox. Reactivation of latent VZV can lead to various neurological complications, including transverse myelitis (TM); although cases of the latter are very rare, particularly in newly active VZV infection.

We report here an unusual case of TM in a middle-aged adult immunocompetent patient that developed concomitant to an active VZV infection. The 46-year-old male presented with painful vesicular eruption on his left chest that had steadily progressed to involvement of his back over a 3-d period. Cerebrospinal fluid testing was denied, but findings from magnetic resonance imaging and collective symptomology indicated TM. He was administered antiviral drugs and corticosteroids immediately but his symptom improvement waxed and waned, necessitating multiple hospital admissions. After about a month of repeated treatments, he was deemed sufficiently improved for hospital discharge to home.

VZV myelitis should be suspected when a patient visits the outpatient pain clinic with herpes zoster showing neurological symptoms.

Core Tip: The occurrence of transverse myelitis (TM) secondary to varicella zoster virus (VZV) in immunocompetent patients is very rare. VZV-TM should be suspected when a patient visits an outpatient pain clinic with herpes zoster and presents neurological symptom(s). VZV-TM must be diagnosed early, by magnetic resonance imaging and/or cerebrospinal fluid analysis, since delayed intervention may allow for serious complications to develop. Also, early administration of a combination of antiviral drugs and corticosteroids may help resolve the condition and relieve the associated pain experienced by patients with TM secondary to VZV.

- Citation: Yun D, Cho SY, Ju W, Seo EH. Transverse myelitis after infection with varicella zoster virus in patient with normal immunity: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(33): 10308-10314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i33/10308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10308

Among the outpatient population of the pain clinic, a significant number of patient visits are prompted by pain caused by herpes zoster (HZ). Rarely, that pain is accompanied by neurological symptoms; however, in such cases, concomitant transverse myelitis (TM) should be suspected. We describe herein an unusual case of TM shortly following infection by the varicella zoster virus (VZV) and in conjunction with the usual symptomology in immunocompetent patient.

VZV infection is very common and causes chickenpox and HZ[1]. The VZV infection itself is often complicated by postherpetic neuralgia (the most common neurologic complication), VZV vasculopathy, cerebellitis, meningoradiculitis, meningoencephalitis, myelitis, and ocular disease[2]. However, very few cases of VZV-TM have been reported, particularly in an immunocompetent patient. In order to accurately determine VZV as the cause of TM, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is required, despite it being technically difficult to isolate VZV from CSF in VZV patients who have developed myelitis[3]. Additional evaluation of the neurological symptoms by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important for accurate diagnosis, which allows for the timely initiation of treatment and improves prognosis.

A 46-year-old male presented to our hospital with complaint of painful vesicular eruption that had begun 3 d prior on his left chest and steadily progressed to involvement of his back.

The patient characterized the pain as ‘stinging’ and reported that it had begun after he participated in strenuous outdoor activities. He noted that the pain was accompanied by the vesicle eruption. He denied any history of trauma.

The patient denied VZV infection (i.e. chickenpox or any form of HZ) in his medical history.

The patient’s other personal and family medical history was unremarkable for this case.

Vesicular eruption was present on the left chest to the axillary side, being limited within the T5-T8 dermatome (Figure 1). Using the visual analogue scale (VAS), the patient classified the stinging pain intensity of the vesicle eruption as 7.

Blood tests for serum VZV immunoglobulin (Ig) M and VZV IgG were positive.

Chest computed tomography (CT) findings were nonspecific.

The patient was diagnosed with HZ and ordered treatment with an antiviral drug (Clovir tablet, famciclovir at 250 mg bid; Dong Wha Pharm, Seoul, Korea), steroid (dexamethasone at 5 mg bid; Daewon Pharm, Busan, Korea), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Naxozole tablet, esomeprazole strontium 24.6 mg/naproxen 500 mg bid (Hanmi Pharm, Seoul, Korea); Valentac, declofenac sodium at 75 mg/mL intramuscular injection (WhanIn Pharm, Seoul, Korea). After 1 wk, the patient showed improvement (Figure 2), with pain score reducing to VAS 2, and was discharged to home.

However, 10 d after discharge, the patient returned to the hospital with complaint of pain recurrence (VAS 7-8) and was referred to our pain clinic. The same dermatome region showed re-eruption of the vesicles. Upon readmission, we administered ultrasound-guided erector spina plane block (commonly referred to as ESPB) and prescribed Lyrica Capsules (pregabalin at 75 mg bid; Pfizer, New York, NY, United States) and Targin prolonged-release (oxycodone at 5 mg/naloxone at 2.5 mg bid; Mundipharma, Seoul, Korea) for pain control. After the ESPB, the patient reported his pain reduced to VAS 2 and he was again discharged. At 2 d later, however, his pain worsened (VAS 6–7), and he returned to hospital and was again readmitted for pain control. This time, we inserted a patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) port. First, with the patient in prone position, an 18-G Tuohy needle was advanced using the paramedian approach at the thoracic spine level 9–10 under C-arm guidance. The epidural space was identified using loss-of-resistance technique and the contrast medium was injected. After confirming loss-of-resistance using C-arm, a flexible epidural catheter was passed cranially for about 2–3 cm and secured with the skin. Initially, the port was used to administer 300 mL of 0.1% ropivacaine at a continuous infusion rate of 4 mL/h via a disposable silicone balloon infuser (AutoFuser; ACE Medical, Beverly Hills, CA, United States). During the maintenance of PCEA, the patient reported his pain to be reduced to VAS 3. However, that night, the patient began to experience difficulty urinating as well as mild motor weakness (motor grade 4) and paresthesia in the bilateral distal lower extremities. The epidural catheter was removed immediately.

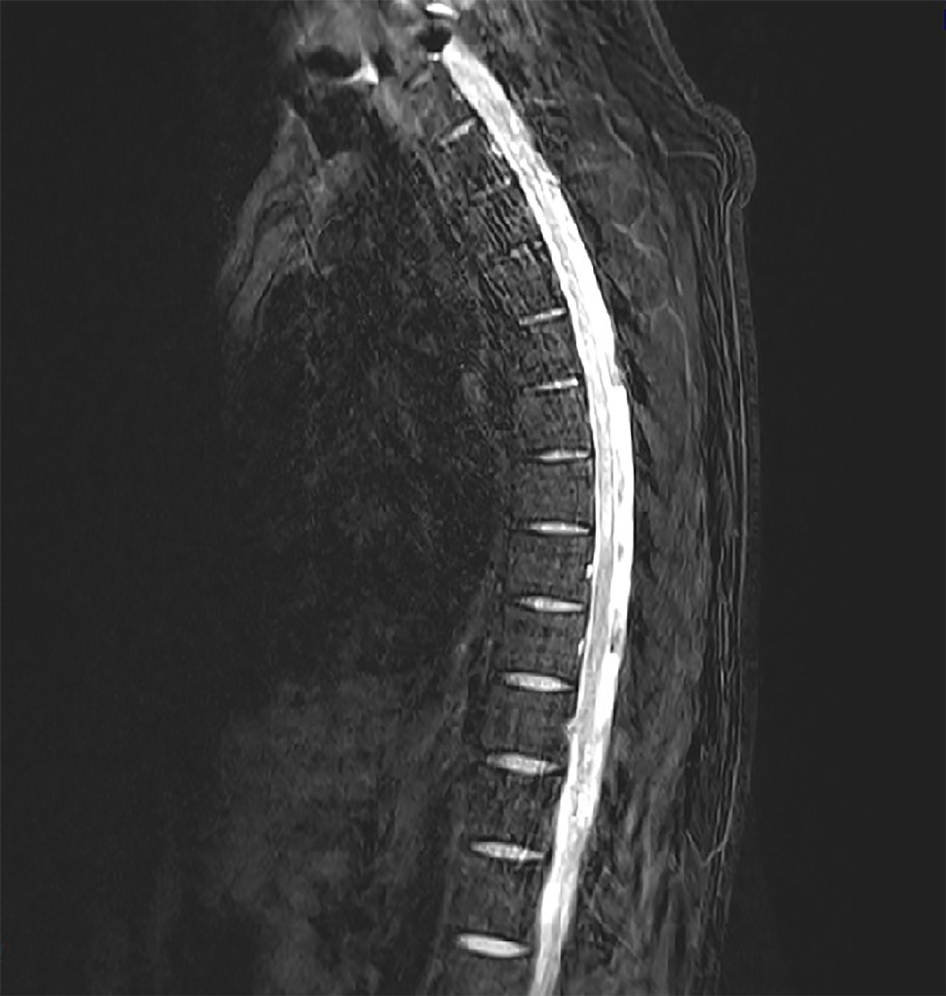

A catheter tip culture was ordered but revealed no microorganism. To rule-out central nervous system infection, a T-spine MRI was performed. The T2-weighted images showed high signal intensity within the left spinal cord level T2-8 (Figure 3). The neurologic examination revealed mild paresthesia and normal motor strength at the bilateral distal lower-half extremities and hyperactive deep tendon reflex on the left side. The need for a CSF study was explained, but the patient’s guardian refused consent.

Based on the patient’s overall clinical presentation profile and imaging findings, he was diagnosed with VZV and myelitis.

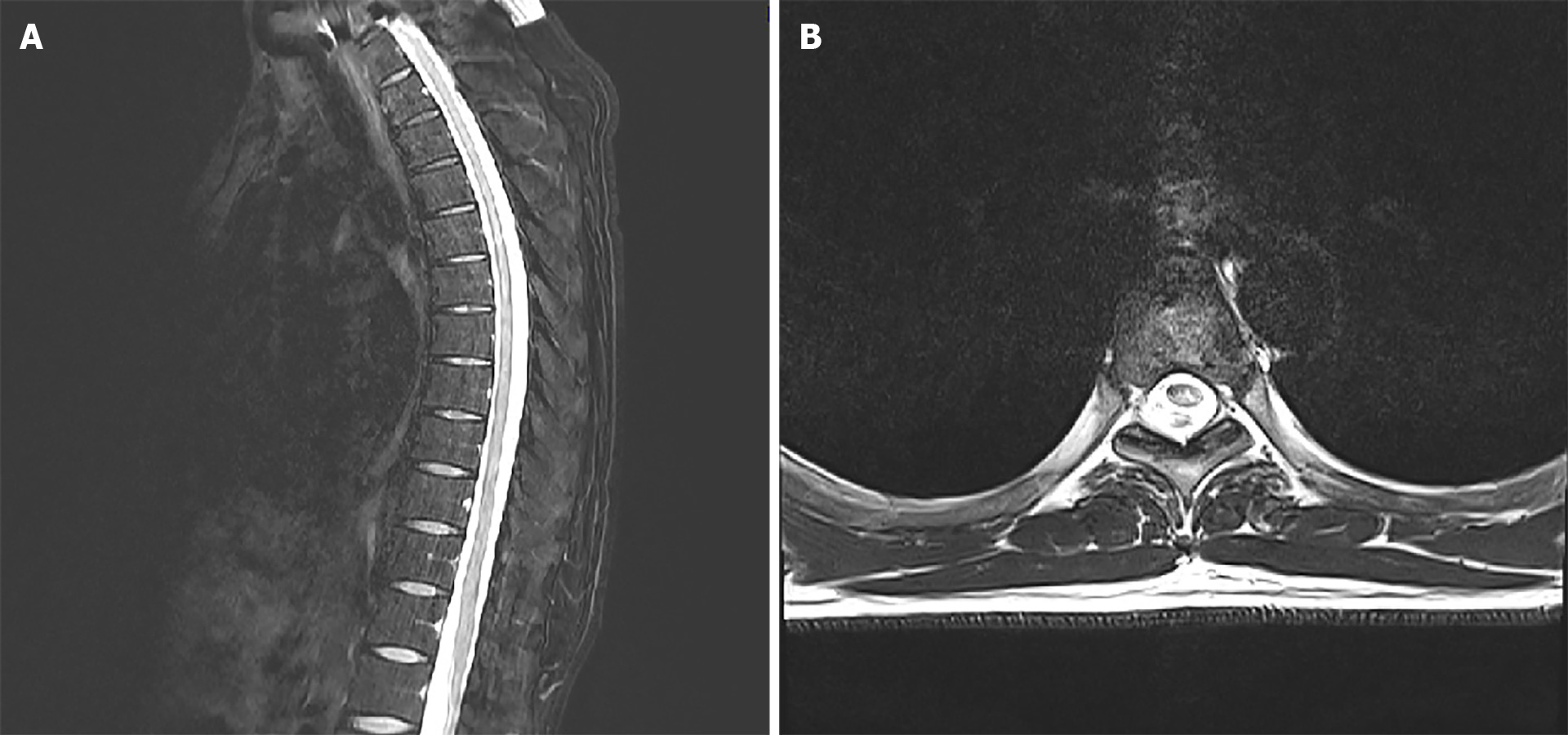

A 1-wk course of Clovir (acyclovir 250 mg tid; Myung-In Pharm), Maxipime (cefepime at 1 g bid; Boryung, Seoul, Korea) and Solondo tablet (prednisolone at 5 mg tid; Yuhan, Seoul, Korea) was initiated; in addition, the patient was administered Targin prolonged-release (oxycodone at 5 mg/naloxone at 2.5 mg bid; Mundipharma) and Lyrica Capsules (pregabalin at 75 mg bid; Pfizer) for pain control. The patient reported his pain to remain at about VAS 3 with these medications. The acyclovir as discontinued after the 1-wk course. A follow-up MRI was performed 3 wk later, and did not show any significant changes (Figure 4). At this time, the patient reported his pain to be well controlled (VAS 2) and findings from neurological examination were normal, allowing for discharge to home.

At the outpatient follow-up visit, conducted 1 mo after discharge, the patient had no neurologic symptoms but residual pain (VAS 2) that involved the area from the chest to the axillary side of the T5-T8 dermatome.

VZV is a human neurotropic and double-stranded DNA alpha-herpesvirus—the primary infection of which usually occurs during childhood and manifests as chickenpox[1]. After the primary infection, VZV becomes latent in the cranial root ganglia or dorsal root ganglia and can remain so for several decades; however, in elderly or immunocompromised individuals, it can become reactivated and recur as HZ[3,4].

HZ itself is associated with a variety of complications, such as HZ vasculitis and ophthalmic, neurologic or visceral disease. The most common neurological complication is postherpetic neuralgia, a chronic neuropathic pain that persists after resolution of the HZ skin rash. Other complications include cranial nerve or peripheral nerve palsy, myelitis, meningoencephalitis, and stroke[2].

Only 0.3% of patients reported with HZ manifestation experience TM[5]. In general, about 25%-50% of TM cases are caused by viral infections, including herpes virus or poliovirus. Though HZ infection is common, even in immunocompetent patients, it rarely progresses to TM. In Korea, in particular, only a few cases of TM secondary to VZV have been reported. Thus, TM secondary to VZV is an abnormal inflammatory finding; yet, the literature indicates that it can involve all parts of the spinal cord and that the pathogenesis may be related directly to the viral invasion and consequent axonal degeneration[6].

Symptoms of TM usually develop over a period of hours to days and sometimes progress gradually over weeks. Mostly, it involves both sides of the body below the affected area of the spinal cord, but there are cases wherein it appears to affect only one side. Common signs and symptoms include pain (back, abdomen, chest), abnormal sensation, weakness in arms or legs, and bladder and bowel problems[7].

TM is diagnosed based on the patient’s signs and symptoms, medical history, and clinical assessment of nerve function. If several diagnostic workups, including MRI, CSF analysis and complete blood count, provide evidence of inflammation, TM can be diagnosed after ruling out of other causes. MRI is one of the most effective diagnostic tools for TM secondary to VZV. In MRI, VZV myelitis is shown as hyperintensity in the spinal cord on T2-weighted images[8]. CSF analysis can then be done as a confirmatory test. Unfortunately, however, the procedure of CSF analysis is actually quite complicated; the VZV must first be separated from the CSF sample (invasively acquired) and must then demonstrate presence of VZV antigen via immunofluorescence assay. Indeed, in some cases reported in the literature, the VZV antibody was not found in the CSF sample and patient was diagnosed by MRI findings alone[3,9]. Likewise, no CSF study was conducted for our patient and the diagnosis was made according to the collective profile of clinical symptoms and MRI findings.

In TM, early therapeutic intervention is essential to minimize complications and pain extent and duration suffered by the patient. The intervention must be tailored to the patient’s symptoms, since there is yet no standardized treatment regimen for TM secondary to VZV. Currently, the accepted treatment regimen should include an antibiotic, antiviral, high-dose corticosteroid, and intravenous Ig[3,6]. However, the efficacy of no specific treatment regimen has not been systematically demonstrated[10]. Of note, however, a study found that the combination of acyclovir and corticosteroids effectively reduced acute neuritis in VZV myelitis patients, and the most important prognostic factor was determined to be early medical intervention[5]. Another study showed that after administration of antivirals and steroids, the interval prior to symptom improvement ranged from 3 d to 9 d, with complete recovery seen in 10 d, but some patients were left with permanent neurological deficits, such as weakness or numbness, or had even progressed to encephalitis[11]. In our case, the early application of a combination treatment involving antivirals and corticosteroids significantly relieved the patient’s symptoms.

The occurrence of TM secondary to VZV in immunocompetent patients is very rare. VZV myelitis should be suspected when a patient visits the outpatient pain clinic with HZ showing neurological symptoms. VZV myelitis must be diagnosed early, using MRI and CSF study, since delayed intervention may allow for serious complications to develop. Also, early application of a combination treatment approach using antivirals and corticosteroids may benefit patients with TM secondary to VZV.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kim YH S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Gilden D, Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R. The variegate neurological manifestations of varicella zoster virus infection. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kovac M, Lal H, Cunningham AL, Levin MJ, Johnson RW, Campora L, Volpi A, Heineman TC; ZOE-50/70 Study Group. Complications of herpes zoster in immunocompetent older adults: Incidence in vaccine and placebo groups in two large phase 3 trials. Vaccine. 2018;36:1537-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yýlmaz S, Köseolu HK, Yücel E. Transverse myelitis caused by varicella zoster: case reports. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:179-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagel MA, Gilden D. Neurological complications of varicella zoster virus reactivation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2014;27:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee CC, Wu JC, Huang WC, Shih YH, Cheng H. Herpes zoster cervical myelitis in a young adult. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:605-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ari BC, Karaci R, Domac FM, Ulker M, Bolluk B, Ofluoglu D, Ozgen Kenangil G. Transverse Myelitis Caused by Varicella Zoster Virus: A Case Report. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2019;27:231-233. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Frohman EM, Wingerchuk DM. Clinical practice. Transverse myelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:564-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee JE, Lee S, Kim KH, Jang HR, Park YJ, Kang JS, Han SY, Lee SH. A Case of Transverse Myelitis Caused by Varicella Zoster Virus in an Immunocompetent Older Patient. Infect Chemother. 2016;48:334-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ong OL, Churchyard AC, New PW. The importance of early diagnosis of herpes zoster myelitis. Med J Aust. 2010;193:546-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dworkin RH, Johnson RW, Breuer J, Gnann JW, Levin MJ, Backonja M, Betts RF, Gershon AA, Haanpaa ML, McKendrick MW, Nurmikko TJ, Oaklander AL, Oxman MN, Pavan-Langston D, Petersen KL, Rowbotham MC, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Tyring SK, van Wijck AJ, Wallace MS, Wassilew SW, Whitley RJ. Recommendations for the management of herpes zoster. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44 Suppl 1:S1-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de Silva SM, Mark AS, Gilden DH, Mahalingam R, Balish M, Sandbrink F, Houff S. Zoster myelitis: improvement with antiviral therapy in two cases. Neurology. 1996;47:929-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |