Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9982

Peer-review started: June 25, 2021

First decision: August 18, 2021

Revised: August 31, 2021

Accepted: September 15, 2021

Article in press: September 15, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 137 Days and 8.9 Hours

Both squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) are common malignant tumors in the neck. However, seldom has SCC of the thyroid been diagnosed. Further, cytological features of SCC and PTC have rarely been reported. The significance of fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in the diagnosis of neck masses has been established. Herein, we present an exceedingly rare case of an intrathyroidal SCC diagnosed using FNAC, along with its cytological features.

A 66-year-old man presented with a left-sided neck mass. Ultrasound examination showed an ill-defined nodule. The appearance was hypoechoic with a few hyperechoic spots. FNAC of the left thyroid nodule was performed. A cellular smear was obtained, and it showed a large number of neoplastic cells with rich cytoplasm and poor cell adhesion. Tumor cell nuclei showed coarse nuclear chromatin and a few enlarged prominent nucleoli. An increased nuclear/cytoplasm ratio was observed. Thus, malignancy was diagnosed without a confirmed tumor type. Percutaneous tumor biopsy was performed to make a definite diagnosis. The tumor cells showed typical squamous cell characteristics.

Head and neck SCC and PTC have different cytologies. Measures are needed to ensure accurate diagnosis using FNAC.

Core Tip: Measures such as cell block, immunohistochemical analysis, and genetic testing should be considered to improve the accuracy of diagnosis using fine-needle aspiration.

- Citation: Yu JY, Zhang Y, Wang Z. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of an intrathyroidal nodule diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9982-9989

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9982.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9982

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is an important diagnostic tool in various medical settings. It is a direct first-line approach for the evaluation of palpable and impalpable lesions and is faster to perform and less expensive than conventional histology, especially in cases in which only minimal laboratory infrastructure is available[1,2]. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy has also become an important part of clinical decision-making[3]. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is performed to confirm clinical and radiological suspicions of carcinoma before definitive resection.

FNA is the first choice to differentiate between benign and malignant thyroid nodules at the cellular level[4]. It allows patients with benign and malignant lesions to be triaged, thus facilitating optimum clinical and/or surgical management[5]. Thyroid FNA offers a high positive predictive value (97%-99%), with sensitivities and specificities of 65%-99% and 72%-100%, respectively[5]. The main goal of performing thyroid FNA is to triage patients to surgery, who have nodules with a high risk of malignancy, while avoiding unnecessary surgical procedures in others[6]. The minimally invasive and rapid procedure involves the use of a narrow-gauge needle to obtain a sample of a lesion for microscopic examination. During this procedure, thyroid biopsy specimens are classified by their cytological appearance as benign, suspicious (or indeterminate), or malignant. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology has been accepted worldwide[5]. Among malignant thyroid tumors, papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), an indolent carcinoma with a good prognosis, is the most common[7].

However, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCs) account for approximately 750000 cases worldwide and cause 40000 deaths annually, thereby threatening human health and life[8]. Occasionally, HNSCs can be first recognized as a mass in the neck. HNSCs are characterized by metastasis and local invasion. They show a high recurrence rate after surgery or radiotherapy, and patients have a poor quality of life[9]. Direct nasopharyngolaryngoscopy is routinely performed to diagnose HNSCs, and biopsy can be performed if necessary[9]. Owing to its unique cytomorphologic and structural features, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) can be diagnosed easily.

Few studies have reported on the cytomorphologic features of intra-thyroidal SCC using FNAC[10]. Herein, we present a case of an intrathyroidal SCC that presented as a giant neck mass and was suggested as being malignant after FNAC. Considering HNSCs and PTCs are both common primary malignant tumors in the neck, with HNSCs showing a poor prognosis and PTCs showing better recovery and survival rates, accurate diagnosis using FNA is not possible. Besides, the survival rate of patients with early-diagnosed HNSCs can be as high as 75%-80%; however, most patients are not diagnosed until the late stage with a long-term survival rate of only 35%[11]. No adequate evidence on differentiating HNSCs and PTCs using FNA is available. Further, methods allowing a differential diagnosis of HNSCs and PTCs at the cellular level have seldom been discussed. Therefore, in this case report, we describe the cytological features of an intrathyroidal SCC with an unusual presentation to serve as a reference for similar such cases in the future. We also compare the cytological features of HNSCs and PTCs and provide additional measures to ensure an accurate diagnosis using FNAC.

A 66-year-old man presented to our hospital complaining of a left-sided neck mass for 45 d.

The patient noticed the mass approximately 45 d before our consultation. He complained of throat pain and difficulty in swallowing. He denied any dysphagia, dyspnea, bleeding, or body weight changes.

The patient mentioned a past medical history of hyperthyroidism and has been receiving the medication for the condition for over 10 years (propylthiouracil 50 mg once every other day).

The patient had no other significant past history or family history.

Physical examination revealed a large, firm, painless, left-sided neck mass approximately 4 cm in size. No enlarged lymph nodes were noted.

Blood analysis revealed that thyroid peroxidase and antithyroid globulin antibody levels were dramatically increased (757.97 IU/mL and 669.81 IU/mL, respectively). However, the levels of free triiodothyronine, free tetraiodothyronine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone were in normal range.

Ultrasound examination revealed a 4.5 cm × 3.0 cm × 2.8 cm mass in the left thyroid lobe. It was an ill-defined and lobulated nodule that was irregularly shaped, with hypoechoic and a few hyperechoic spots visible on ultrasound. Per the thyroid imaging reporting and data system (TI-RADS), the nodule was classified as TI-RADS 5 (Figure 1A and B). Further, enhanced computed tomography was performed. It revealed a 45 HU low-density nodule, showing weak consolidation after enhancement. Laryngoscopy showed no abnormalities (Figure 1C-E).

FNA of the thyroid and neck masses was performed. FNA of the thyroid mass showed a cellular smear comprising a large number of neoplastic cells and red blood cells in the background. The neoplastic cells showed poor cell adhesion and were oval or spindle-shaped. They were approximately 2-5 times the size of lymphocytes and were arranged densely in a disorderly manner (Figure 2A). High-power view showed nuclear characteristics, including hyperchromasia and coarse nuclear chromatin with occasional prominent nucleoli. Tumor cells were rich in cytoplasm, although the nuclear/cytoplasm ratio was high. Mitosis was occasionally observed (Figure 2B-D). The cells showed no signs of PTCs, including “Orphan Annie-eye” nuclei, intranuclear pseudoinclusions (due to cytoplasmic invaginations), and nuclear grooves (folds in the nuclear membrane) or psammoma bodies. Immunocytochemical analysis was performed on the FNA smear. The tumor cells showed partial positivity for the expression of p63 and negativity for the expression of thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1 (Figure 2E and F). Furthermore, genetic testing was performed, and no V600E mutation was found in the BRAF gene (Figure 3). On the basis of the mentioned evidence, we considered the tumor to be malignant. However, we could not reach a consensus on its diagnosis as PTC or HNSC. Therefore, we suggested that clinical biopsy be performed to obtain a definite diagnosis.

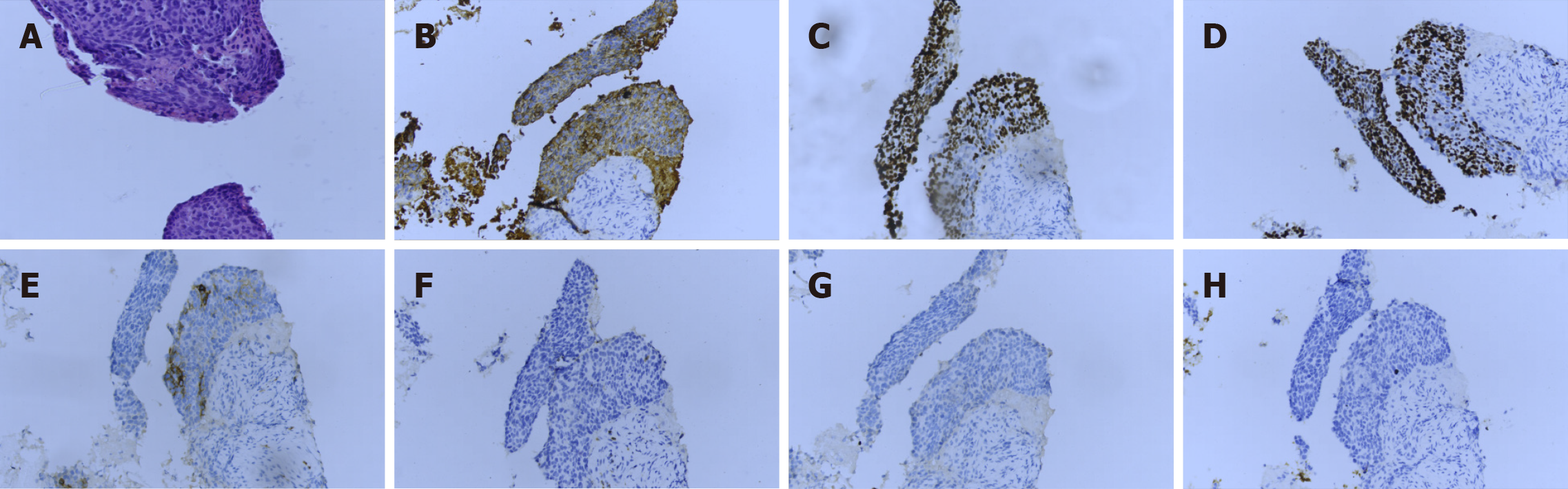

Several sections measuring 0.5-1 cm in length and 0.1 cm in diameter were obtained from the tumor through percutaneous tumor biopsy. Histological sections revealed cellular nests of epithelioid cells surrounded by fibrous cells. At the end of the tissue, normal thyroid follicles were observed (Figure 4A). The tumor cells showed typical squamous cell characteristics. They were arranged in nests next to each other by intercellular bridges, with disordered cell polarity (Figure 4B). The tumor cells had enlarged, hyperchromatic nuclei and rough chromatin, although they were rich in cytoplasm (Figure 4C). A battery of immunohistochemical staining procedures was performed. The tumor cells showed positivity for the expression of cytokeratin (CK), p40, and p63 and negativity for the expression of thyroglobulin (TG), TTF-1, and CD5. Besides, partial positivity for the expression of CD117 was observed (Figure 5A-H). SCC was diagnosed on the basis of this evidence.

The patient underwent surgery to excise the tumor after it was diagnosed as SCC.

There were no postoperative complications, and no metastasis was demonstrated on regular computed tomography scan after 0.6 year of follow-up. The general condition of the patient is quite well.

The cytological manifestations, such as intranuclear pseudoinclusions or nuclear grooves, in our case did not correspond to those in PTCs. No V600E mutation was found in the BRAF gene, which indicated a low probability of PTC. In addition, the tumor cells were found to be negative for the expression of TTF-1, which ruled out PTC. Cytological manifestations in this case included non-adhesive clusters of monomorphic cells with rich cytoplasm and enlarged nuclei, which could be considered epidermal-like cells. These features indicated a malignant tumor, thus making diagnosis using FNA difficult. Further, histological sections revealed cellular nests of epithelioid cells surrounded by fibrous cells. Tumor cells showed the presence of intercellular bridges, bizarrely shaped cells, and dense cytoplasm-features specifically associated with squamous differentiation. Immunohistochemical staining was performed. The tumor cells showed positivity for the expression of CK, p40, and p63 and negativity for the expression of TG, TTF-1, and CD5. P40 and p63 positivity indicates squamous differentiation of tumor cells. TG and TTF-1 negativity indicates that the tumor did not originate from the thyroid gland. SCC was diagnosed on the basis of histological findings.

Our case reveals that morphological features on cytological smears can indicate malignancy, however, subclassification and distinction are difficult in a subset of cases, particularly unusual cases. Usually, PTCs can be diagnosed using FNA when they exhibit typical cytological features, such as “Orphan Annie-eye” nuclei, intranuclear pseudoinclusions (due to cytoplasmic invaginations), and nuclear grooves (folds in the nuclear membrane) or psammoma bodies. Besides, the detection of a BRAF V600E mutation has a > 99% specificity for the diagnosis of thyroid cancer. BRAF V600E testing is most useful during high-risk FNA when nuclear features of papillary carcinoma are suggested, although the cytological diagnosis remains uncertain[12]. Besides PTC, high-grade thyroid lymphoma, metastases from other primaries, intrathyroidal parathyroid carcinoma, and other thyroid tumors can be detected using FNA[13,14]. HNSCs arising from the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and nasopharynx have rarely been recognized first in the thyroid. The thyroid is the most common organ to present with neck nodules and is easily accessible via FNA. With the increasing utilization of this tool, one may encounter unusual lesions as well.

Few cytomorphological descriptions of SCCs and PTCs have been reported. Cytomorphological features of SCCs include marked variation in cell number and nuclear size and shape, marked variation in staining intensity (often hyperchromatic), and increased size and number of nucleoli. A high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio can be found as well. Tumor cells are arranged in a disorder manner and exhibit loss of polarity. PTCs also show marked variation in cell number, increased nuclear size, and oval in shape. Further, the nucleus has specific features such as “Orphan Annie-eye,” intranuclear pseudoinclusions (due to cytoplasmic invaginations), and nuclear grooves (folds in the nuclear membrane) or psammoma bodies. These tumor cells are arranged in papillary architecture.

Besides presenting the different cytological features of HNSCs and PTCs, our case reveals the difficulty in the diagnosis of unusual lesions using FNA. The limits of cytological diagnosis can be defined, including limited cell smear specimens and less preservation of the histological architecture because of the small amount of aspired cells. More specifically, specimens obtained by FNA show more cellular features than histological architecture. Thus, cell block cytology with immunohistochemical staining can better contribute to the diagnosis of difficult cases than FNAC. Cell block cytology may help increase the sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing PTCs and HNSCs. Methods to improve the accuracy of diagnosis should be further discussed. First, sufficient cytological specimens should be obtained, and cell block cytology must be considered. Second, immunohistochemical analysis or other supplementary methods such as gene testing may help validate the diagnosis. Third, the experience and diagnostic expertise of the pathologist play an important role in ensuring accurate diagnosis. Knowing the relevant diagnostic pitfalls may also help. Doctors should obtain complete details of the relevant clinical information, such as medical history and ultrasound findings. Further, using standardized reporting terminology for thyroid FNA can be recommended. Unclear diagnosis using FNA may lead to a series of consequences, such as delayed clinical treatment and prolongation of hospitalization.

According to the findings of this case, it is clear that there is a need to focus on improving the diagnosis of such cases through FNA. FNA is widely applied because it is easy to perform and results in few complications. Besides PTCs, high-grade thyroid lymphoma, metastases from other primary sites, intrathyroidal parathyroid carcinoma, and other thyroid tumors can be first detected using FNA[6,7]. Hence, techniques to improve the accuracy of diagnosis should be further studied. Sufficient cytological specimens should be obtained, and cell block cytology should be considered. Additionally, immunohistochemical analysis or genetic testing can be performed for an accurate diagnosis.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Koritala T, Mokni M S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Orell S, Sterret GF, Whittaker D. Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005. |

| 2. | Field AS, Geddie W, Zarka M, Sayed S, Kalebi A, Wright CA, Banjo A, Desai M, Kaaya E. Assisting cytopathology training in medically under-resourced countries: defining the problems and establishing solutions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:273-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rimbaş M, Crino SF, Gasbarrini A, Costamagna G, Scarpa A, Larghi A. EUS-guided fine-needle tissue acquisition for solid pancreatic lesions: Finally moving from fine-needle aspiration to fine-needle biopsy? Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:137-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Choong KC, Khiyami A, Tamarkin SW, McHenry CR. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: Is routine ultrasound-guidance necessary? Surgery. 2018;164:789-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cibas ES, Ali SZ. The 2017 Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Thyroid. 2017;27:1341-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 955] [Cited by in RCA: 1169] [Article Influence: 146.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rossi ED, Adeniran AJ, Faquin WC. Pitfalls in Thyroid Cytopathology. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12:865-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshida Y, Horiuchi K, Okamoto T. Patients' View on the Management of Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: Active Surveillance or Surgery. Thyroid. 2020;30:681-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55839] [Article Influence: 7977.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 9. | Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Update on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:386-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 611] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 89.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vatsyayan A, Mandlik D, Patel P, Sharma N, Joshipura A, Patel M, Odedra P, Dubbal JC, Shah DS, Kanhere SA, Sanghvi KJ, Patel K. Metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck to the thyroid: a single institution's experience with a review of relevant publications. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;57:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11065] [Cited by in RCA: 12187] [Article Influence: 1523.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Poller DN, Glaysher S. Molecular pathology and thyroid FNA. Cytopathology. 2017;28:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Alharbi N, Asa SL, Szybowska M, Kim RH, Ezzat S. Intrathyroidal Parathyroid Carcinoma: An Atypical Thyroid Lesion. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Huang CG, Li MZ, Wang SH, Zhou TJ, Haybaeck J, Yang ZH. The diagnosis of primary thyroid lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration, cell block, and immunohistochemistry technique. Diagn Cytopathol. 2020;48:1041-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |