Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9948

Peer-review started: June 12, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 2, 2021

Accepted: September 8, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 150 Days and 10.1 Hours

Hepatic hemolymphangioma is an extremely rare benign congenital malformation composed of cystically dilated lymphatic and blood vessels, and they have nonspecific clinical symptoms and laboratory results. In this study, hepatic hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas in an elderly woman was initially reported and analyzed.

A 61-year-old female patient, with a history of hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, was referred to the hepatobiliary surgery department with the complaint of multiple hepatic hemangiomas that had been diagnosed 2 years prior in a preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) examination. Upon entering our hospital, no abnormal physical examination and laboratory data were found. The latest CECT revealed a new 7.0 cm × 6.2 cm cystic-solid lesion with multiple internal divisions in segment II of the liver, with delayed CECT enhancement characteristics that presented as solid parts with internal division. On the positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, no significant uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucse was observed. Finally, hepatic hemolymphangioma was confirmed based on the pathological and immunohistochemical results after surgery. At 1-year follow-up, her posthepatectomy evaluation was uneventful, and she had recovered full activity. In addition, no postoperative recurrent or residual lesion was found on CECT imaging.

Hepatic hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas was reported and observed by CECT and PET/CT imaging.

Core tip: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of hepatic hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas and the associated features observed by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. In addition, this case was beneficial for confirming the pathogenesis of hepatic hemolymphangioma caused by surgery. Finally, posthepatectomy evaluation was uneventful, and no postoperative recurrent or residual lesion was found on CECT imaging, presenting a good prognosis.

- Citation: Wang M, Liu HF, Zhang YZZ, Zou ZQ, Wu ZQ. Hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas in liver of elderly woman with history of gynecological malignancy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9948-9953

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9948.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9948

Hemolymphangioma, also known as angioma lymphaticum, is an extremely rare vascular malformation that is characterized by blood vessels and cystic dilated lymphatics, which can occur at any age[1,2], with an estimated incidence from 1.2 to 2.8 per 1000 newborn infants[3], and both sexes are equally affected. Hemolymphangioma is considered to be a benign and noninvasive disorder, which is most commonly found in the cervical region[4], seldomly in the pancreas and spleen[5], and even more rarely in the liver. In a review of PubMed, only three hepatic hemolymphangiomas have been reported in the literature thus far[6-8]. In this study, we present for the first time, a hepatic hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas after hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy, in the hope of improving our understanding of hemolymphangioma. Moreover, the imaging features of hepatic hemolymphangiomas observed by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) and positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) were also analyzed.

A 61-year-old female patient was referred to the hepatobiliary surgery department, with the complaint of multiple hepatic hemangiomas that had been diagnosed 2 years prior.

The patient was receiving maintenance chemotherapy after surgery for ovarian cancer.

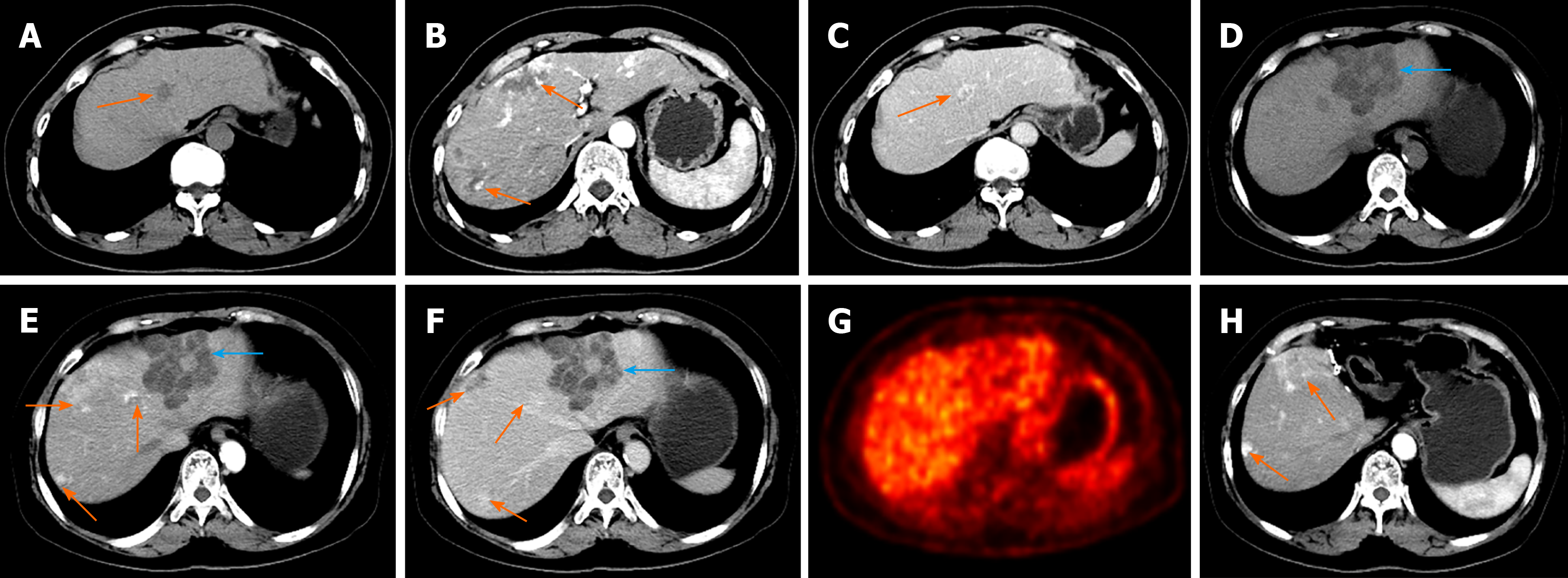

The patient had a 2-year history of hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy owing to ovarian cancer. At her preoperative CECT examination, multiple uniform hypointensity lesions within the liver were found, which were preliminarily diagnosed as multiple hepatic hemangiomas, with the largest lesion measuring 3.6 cm × 2.2 cm, presenting with the enhancement feature of fast-in and slow-out (Figure 1A-C). Based on recommendations from the clinician, the patient was willing to receive regular follow-up.

The patient had no specific personal or family history.

Physical examination revealed that the abdomen was soft without tenderness or an enlarged liver, and no abnormal temperature or heart pressure was noted. The risk factors for history of hepatitis, nausea and vomiting, yellowish discoloration of the skin and weight loss were initially absent 3 years ago and at this presentation.

The laboratory data concerning liver function were normal: alanine transaminase, 11 (7–40) μ/L; aspartate transaminase, 20 (13–35) μ/L; albumin, 42.4 (35.0–53.0) g/L; and direct bilirubin, 4.8 (0.1–5.8) μmol/L. In addition, tumor biomarkers, such as -fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen (CA)-199, and CA-125, were all negative.

Upon entering our hospital on this occasion, the latest CECT was performed and revealed multiple hepatic hemangiomas with the same size and density as the previous CECT (3 years ago). However, a new 7.0 cm × 6.2 cm cystic-solid lesion with multiple internal divisions was found in segment II of the liver. The delayed CECT enhancement characteristics presented as solid parts with internal division (Figure 1D-F), which was considered by a radiologist to be a cystoma or cystadenocarcinoma of the liver. There were no CECT manifestations of enlarged lymph nodes or other abdominal organ metastases. On the PET/CT scan, no significant uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose was observed (Figure 1G).

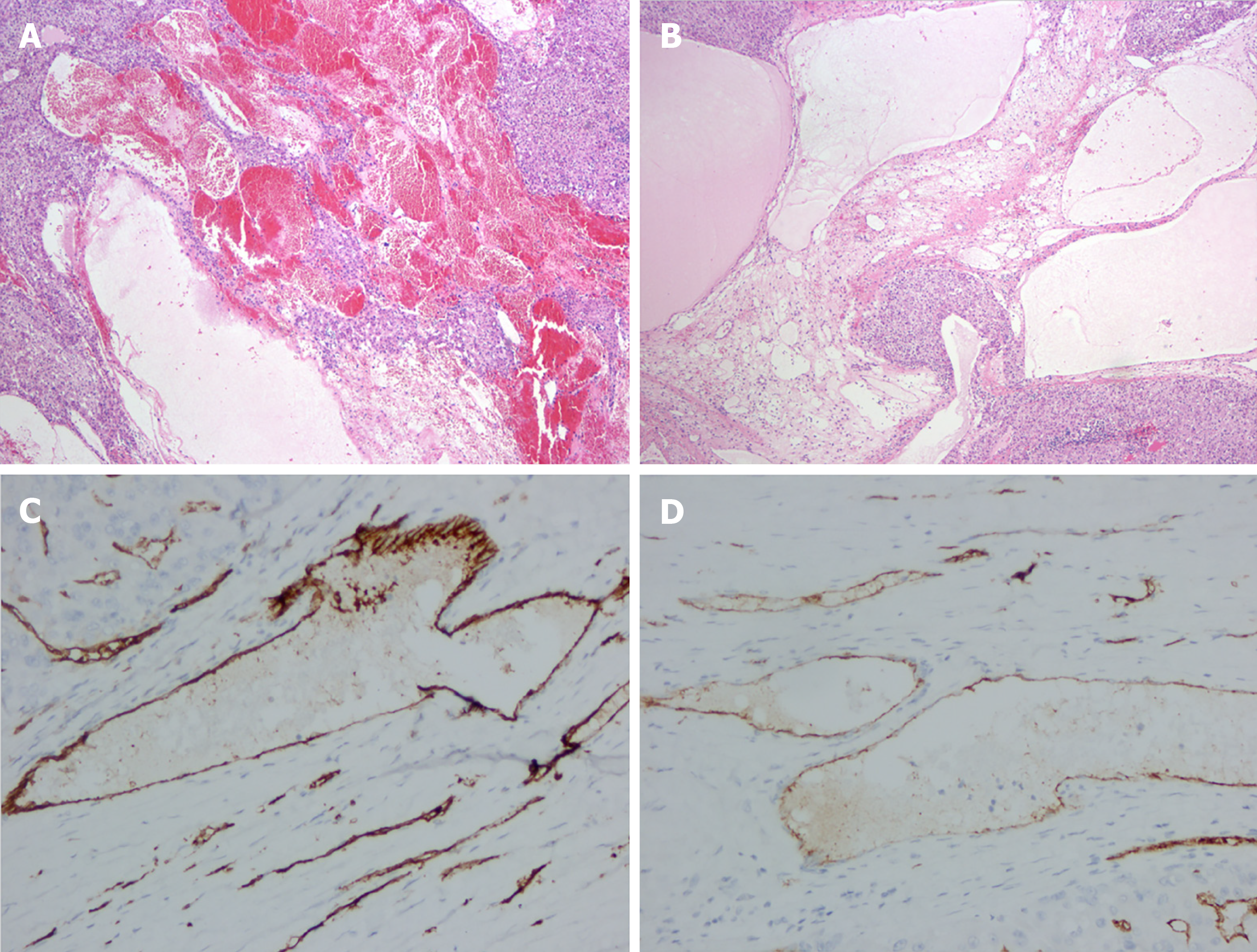

Postoperative pathology demonstrated that the lesion was soft with a honeycomb shape. Microscopically, enlarged lymphatics and capillaries of varying sizes were seen mixed with a few lymphocytes and red blood cells (Figure 2A, B). For immunohistochemical staining (Figure 2C, D), D2-40 (+), vimentin (+), CD31 (+), CD34 (+), cytokeratin (–), S-100 (–), and smooth muscle actin (–) were used.

Hepatic hemolymphangioma was confirmed based on the pathological and immunohistochemical results.

The patient underwent partial hepatectomy under general anesthesia. A 5.4 cm × 3.2 cm well-defined and dark-red lesion with a false capsule was present in the left lobe and protruding from the liver surface. After the operation, neither radiotherapy nor immunotherapy was conducted, and no surgical complications or symptoms occurred.

At 1-year follow-up, posthepatectomy evaluation was uneventful, and the patient had recovered full activity. In addition, no postoperative recurrent or residual lesion was found on CECT imaging (Figure 1H).

Hemolymphangioma can be divided into congenital and acquired forms based on its pathogenesis. For congenital hemolymphangioma, the pathogenesis is mainly associated with obstruction of venous–lymphatic communication between the systemic circulation and dysembryoplastic vascular tissues[9]. However, lymphatic vessel injury caused by surgery or trauma with inadequate lymph fluid drainage can contribute to acquired hemolymphangioma[10]. In the present patient, acquired hemolymphangioma was more likely to be the diagnosis, not only because of the 2-year history of gynecological malignancy, but also because no suspicious hepatic hemolymphangioma was found on preoperative CECT examination. Therefore, this study indicated that surgery may contribute to the pathogenesis of hepatic hemolymphangioma, which was consistent with the previous conclusion reported by Mao et al[11].

The majority of patients with hepatic hemolymphangioma are asymptomatic for a long period of time, and a few patients may present with primary clinical symptoms of nonspecific epigastric discomfort or pain that originates from the tumor as it grows[12]. In addition, the laboratory data of liver function and tumor biomarkers are often negative, which was also demonstrated in the present case. Abdominal imaging is valuable in evaluating the morphology and invasion of the tumor and guiding surgical treatment. Based on the literature review, hepatic hemolymphangioma usually demonstrates a well-demarcated cystic-solid tumor that has a small solid part and multiloculated cyst. The small solid part may be caused by residual and compressed vascular tissue, while a multiloculated cyst may represent rupture and fusion of the vascular cavity[13]. In this case, hepatic hemolymphangioma appeared as gradual delayed enhancement of the internal division and cystic wall, suggesting minimal blood supply by the portal vein in the lesion. However, multilocular cysts with internal division in hepatic lesions are a common but atypical imaging feature. Thus, cystadenomas, cystadenocarcinomas, and intrahepatic hematomas pose a challenge to reaching a definitive diagnosis before surgery[14].

Hepatic hemolymphangioma is commonly considered as a benign disorder, but the recurrence and invasion of adjacent organs have been reported[5]. Complete hepatectomy is the most effective therapy, with the aim to remove the entire tumor; however, careful performance is required to avoid possible hemorrhage, not only because of the vascular component of hemolymphangioma, but also the rich blood supply from the portal vein and hepatic artery. Angiography and embolization can also be performed in cases of acute bleeding. The majority of cases in the literature had successful postoperative treatment, and remained asymptomatic during postoperative follow-up, as did our case. However, the recurrence rates vary depending on the adequacy of the excision. Lesions that have been completely excised present 10%–27% recurrence, while those being partially resected may recur in 50%–100% of cases[15,16]. Therefore, postoperative follow-up is necessary due to the potential recurrence of the tumor.

We described a patient diagnosed with hepatic hemolymphangioma with multiple hemangiomas in an elderly woman with a history of hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy and analyzed the features observed by CECT and PET/CT imaging, which is useful to improve our understanding of hepatic hemolymphangioma. In addition, this study was beneficial for proving the pathogenesis of hepatic hemolymphangioma caused by surgery.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elpek GO, Liakina V, Marickar F S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Mei Y, Peng CJ, Chen L, Li XX, Li WN, Shu DJ, Xie WT. Hemolymphangioma of the spleen: A report of a rare case. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5442-5444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li Y, Zhang X, Pang X, Yang L, Peng B. Occipitocervical Hemolymphangioma in an Adult with Neck Pain and Stiffness: Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:7317289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pan X, Dong Y, Yuan T, Yan Y, Tong D. Two cases of hemolymphangioma in the thoracic spinal canal and spinal epidural space on MRI: The first report in the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e9524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Teng Y, Wang J, Xi Q. Jejunal hemolymphangioma: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang Z, Ke Q, Xia W, Zhang X, Shen Y, Zheng S. An Invasive Hemolymphangioma of the Pancreas in a Young Woman. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2018;21:798-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Damascelli B, Spagnoli I, Garbagnati F, Ceglia E, Milella M, Masciadri N. Massive lymphorrhoea after fine needle biopsy of the cystic haemolymphangioma of the liver. Eur J Radiol. 1984;4:107-109. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Daudet M. [Reflections apropos of a case of hepatic hemolymphangioma of the infant. Operation recovery]. Pediatrie. 1965;20:445-451. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Hu HJ, Jing QY, Li FY. Hepatic Hemolymphangioma Manifesting as Severe Anemia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:548-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Figueroa RM, Lopez GJ, Servin TE, Esquinca MH, Gómez-Pedraza A. Pancreatic hemolymphangioma. JOP. 2014;15:399-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen G, Cui W, Ji XQ, Du JF. Diffuse hemolymphangioma of the rectum: a report of a rare case. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1494-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mao CP, Jin YF, Yang QX, Zhang QJ, Li XH. Radiographic findings of hemolymphangioma in four patients: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ohsawa M, Kohashi T, Hihara J, Mukaida H, Kaneko M, Hirabayashi N. A rare case of retroperitoneal hemolymphangioma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;51:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pan L, Jian-Bo G, Javier PTG. CT findings and clinical features of pancreatic hemolymphangioma: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qian LJ, Zhu J, Zhuang ZG, Xia Q, Liu Q, Xu JR. Spectrum of multilocular cystic hepatic lesions: CT and MR imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33:1419-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kosmidis I, Vlachou M, Koutroufinis A, Filiopoulos K. Hemolymphangioma of the lower extremities in children: two case reports. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang DY, Lu Z, Ma X, Wang QY, Sun WL, Wu W, Cui PY. Multiple Hemolymphangioma of the Visceral Organs: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |