Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9896

Peer-review started: June 9, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: July 5, 2021

Accepted: August 31, 2021

Article in press: August 31, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 153 Days and 11.9 Hours

Acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is a rare condition associated with a high mortality rate. The treatment strategy for MVT is clinically challenging due to its insidious onset and rapid development, especially when accompanied by kidney transplantation.

Here we present a rare case of acute MVT developed 3 years after renal transplantation. A 49-year-old patient was admitted with acute abdominal pain and diagnosed as MVT with intestinal necrosis. An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed to remove the infarcted segment of the bowel. Immediate systemic anticoagulation was also initiated. During the treatment, the patient experienced bleeding, anastomotic leakage, and sepsis. However, after aggressive treatment was administered, all thrombi were completely resolved, and the patient recovered with his renal graft function unimpaired.

The present case suggests that accurate diagnosis and timely surgical treatment are important to improve the survival rate of MVT patients. Bleeding with anastomotic fistula needs to be treated with caution because of grafts. Also, previously published cases of mesenteric thrombosis after renal transplantation were reviewed.

Core Tip: We present a rare case of acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis developed 3 years after renal transplantation. Despite their infrequency, idiopathic acute mesenteric venous thrombosis with renal transplantation should be considered seriously. The accurate diagnosis and timely surgical treatment are very important to improve the survival rate of patients. Bleeding and anastomotic fistula during treatment need to be treated with caution because of grafts.

- Citation: Zhang P, Li XJ, Guo RM, Hu KP, Xu SL, Liu B, Wang QL. Idiopathic acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis after renal transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9896-9902

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9896.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9896

Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is an uncommon but potentially lethal complication of thrombotic conditions[1]. MVT accounts for 5%-15% of all mesenteric ischemia and 6%-9% of cases of acute mesenteric ischemia[2]. Recent improvements and widespread use of diagnostic imaging modalities have facilitated the early recognition of this disease. Early and timely surgical interventions are required when patients present with peritoneal signs or are refractory to initial measures. Medical management with systemic anticoagulation is the cornerstone of modern therapy[3]. MVT is either primary or secondary, and the proportion of primary patients continues to decline due to technology development[4]. Acute MVT has been reported several times in the literature. However, there have been few reports of MVT after renal transplantation.

A 49-year-old male was referred to our emergency department complaining of progressive aggravated abdominal pain for 3 d.

The initial pain was in the hypogastric region and worsened to diffuse abdominal pain 1 d prior, along with nausea, abdominal distension, and vomiting.

The patient had suffered from hypertension for 10 years, which was well controlled medically by nifedipine and metoprolol. His past surgical history of renal transplantation had been 4 years due to chronic kidney disease. The immunosuppression therapy included prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus.

The patient had a free personal and family history.

Clinical examination revealed tenderness on palpation of his full abdomen with rebound tenderness and muscle guarding.

Laboratory evaluation showed that the leucocytes count was elevated at 31 × 109/mL, hemoglobin was 13 g/dL, and C-reactive protein was 33.86 mg/dL. The hepatitis serology and cytomegalovirus results did not suggest clinical virus infection.

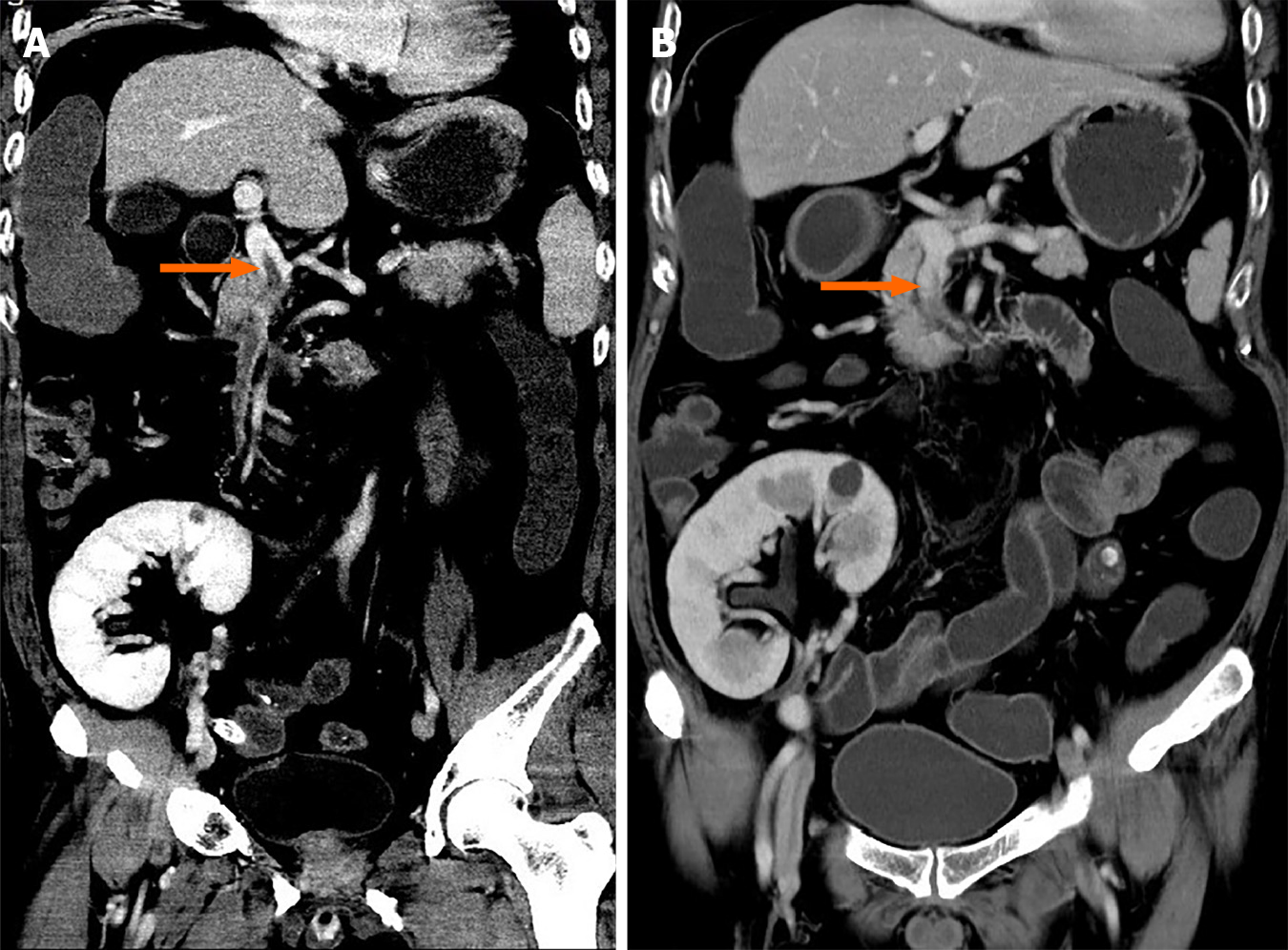

The abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan exhibited an extensive filling defect within the portal vein and right branch, extending to the superior mesenteric vein as well as splenic vein (Figure 1A).

Based on the above findings, a final diagnosis of acute superior MTV was made.

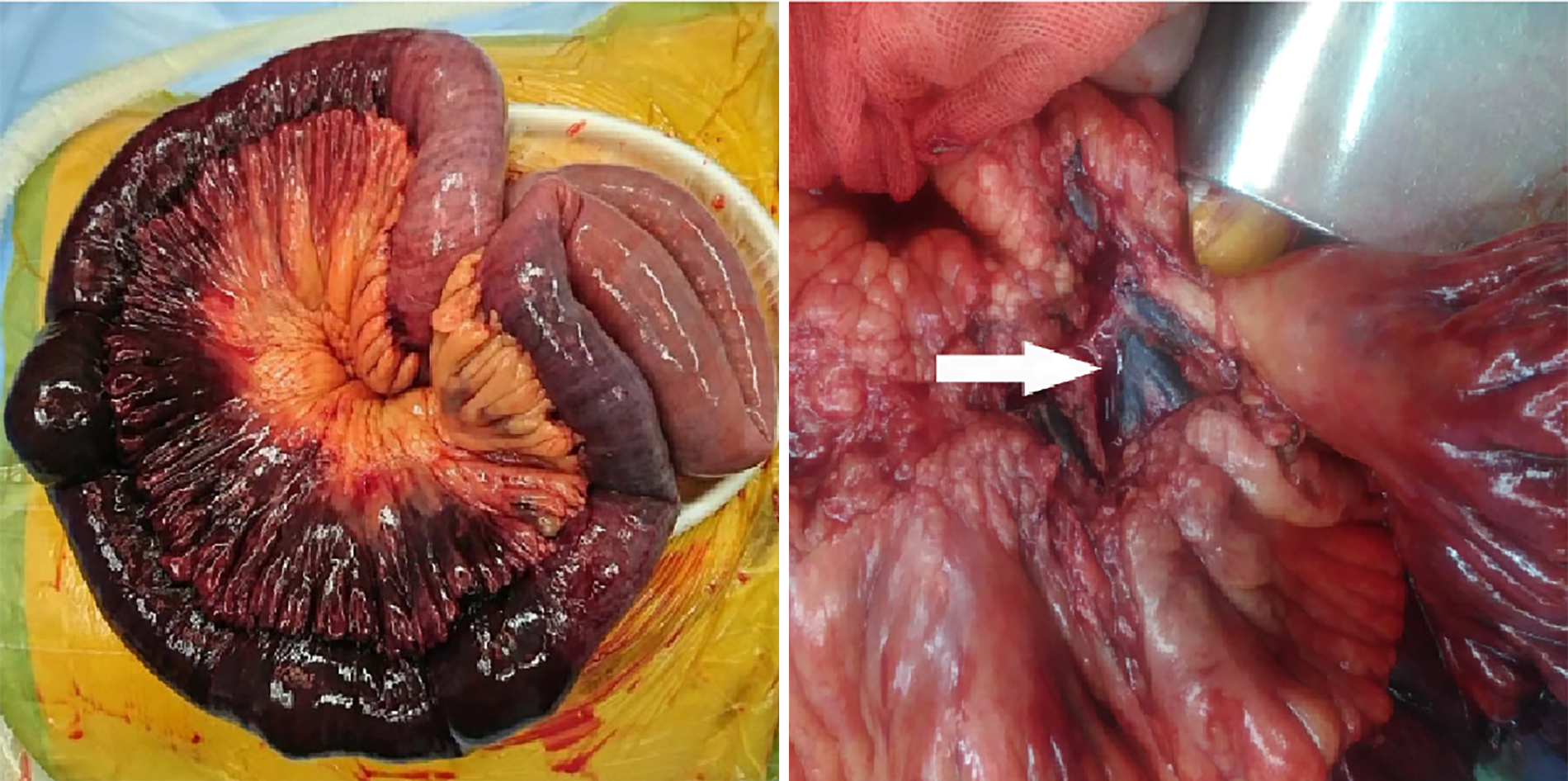

An emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed. On exploration, 600 mL bloody ascites were found, and jejunum, approximately 120 cm from the Treitz ligament, was gangrenous. Almost no pulsations were palpable in the mesentery of the affected bowel, and thromboembolism was discovered in the corresponding mesenteric veins (Figure 2). The necrotic intestine, measuring approximately 100 cm, was resected, and a functional side-to-side anastomosis with staplers was performed. Total parenteral nutrition, intravenous antibiotics, and full anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin were initiated postoperatively. Methylprednisolone was used as a substitute for immunosuppression, and thrombolytic therapy was withheld due to bleeding risk. Further inquiry about the medical history revealed no personal or immediate family history of inherited thrombophilia, deep vein thrombosis, vascular disease, or pulmonary embolism. The patient’s body mass index was 27 kg/m2 without dyslipidemia. Thrombophilia test was negative for the factor V Leiden gene mutation, anticardiolipin antibodies, prothrombin G20210A mutation, and prothrombin gene mutation. The patient had normal levels of homocysteine, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III.

In the following 10 d, the patient recovered well, and the abdominal symptoms improved. On the 11th day after surgery, the patient had a sudden fever of 39 ºC, and ultrasonography showed fluid (55 mm × 10 mm) accumulation surrounding the surgical area. Thus, percutaneous catheterization was performed. On the other hand, the drainage tube of the pelvic cavity was removed. Unexpectedly, a rare hernia happened (Figure 3). The black stool suddenly appeared 3 wk after the operation, with hemoglobin decreasing to 6.5 g/dL. Even more disappointing was radiography from percutaneous catheter revealed anastomotic fistula (Figure 4). The condition worsened because the thrombus was aggravated, and the patient developed a severe bacterial infection with repeated fever to 40 ºC and platelets dropped to 3 × 109/mL (Table 1).

| Lab examinations | Reference range | Preoperation | Postoperation | ||||||

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 10 | Day 26 | Day 28 | Day 42 | |||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 3-9 | 30 | 6 | 11 | 15 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 10 |

| Hb (g/L) | 130-175 | 184 | 126 | 123 | 125 | 117 | 61 | 75 | 96 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 100-350 | 199 | 90 | 78 | 224 | 125 | 26 | 3 | 122 |

| PT (sec) | 11-14 | 15 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 14 | 18 | 17 | 14 |

| Tbili (μmol/L) | 4-23 | 28 | 46 | 111 | 89 | 54 | 15 | 45 | 20 |

| CreaT (μmol/L) | 31-116 | 115.0 | 178 | 118 | 109 | 82 | 102 | 82 | 47 |

Considering the possibility of exacerbating intestinal ischemia, the use of vasopressors and somatostatin was avoided. Anticoagulant therapy was also temporarily discontinued due to the risk of massive bleeding. To balance the healing of the anastomosis, the hormones for immunosuppression therapy were reduced. Anti-infective therapy had also been strengthened, and the bleeding was finally stopped after a whole week of blood transfusion and mucosal protection treatment. The condition was gradually controlled in the following 2 wk, and anticoagulation therapy with dalteparin sodium was initiated. CT scan showed decreased portal vein thrombosis, and thrombosis in the splenic vein was completely absorbed. Although still with intestinal fistula, the patient gradually returned to a normal diet, and anticoagulation therapy was changed to rivaroxaban. The patient was discharged when another CT demonstrated all thrombi were completely absorbed 2 mo after operation (Figure 1B).

On follow-up, the anticoagulation therapy was continued for an additional 4 mo, and the drainage tube for the anastomotic fistula was removed. Until now, no abnormalities were observed in the 2-year follow-up.

MVT is an uncommon, life-threatening disease, which accounts for less than 10% of cases of acute mesenteric ischemia[1]. It is characterized by an insidious onset, and early non-specific clinical presentation but can progress rapidly. The superior mesenteric vein does not have collateral vessels; its complete obstruction accompanied by improper venous drainage can easily result in bowel infarction. Abdominal pain is the most common clinical manifestation of acute superior MVT (SMVT) and is largely determined by the location and extent of the thrombus, the size of the involved vessels, and the depth of bowel-wall ischemia[5]. For this patient, abdominal symptoms gradually worsened with the development of peritonitis, which indicated a complete embolization of a wide range of blood vessels.

Successful treatment of acute SMVT relies on prompt diagnosis. Until now, there has been no single laboratory marker that is sensitive and specific for SMVT. D-dimer testing has the potential to detect thrombosis, and the level in the blood can significantly rise when a thrombus is present[6]. However, D-dimer testing is non-specific, can be elevated duo to abdominal inflammation, and has not been well studied in the evaluation of SMVT. CT scan with arterial and portal phase is the most effective tool, with high sensitivity (96%) and specificity (94%). Image features of CT for bowel ischemia can be divided into mural, vascular, and extramural-nonvascular signs, from which one can make a timely and accurate diagnosis easily[7].

In general, MVT can be classified as primary or secondary depending based on its cause. Secondary MVT can result from various underlying diseases and acquired risk factors, including primary hypercoagulable states or prothrombotic disorders[8], myeloproliferative neoplasms, cancer, diverse inflammatory conditions, trauma, post-operative condition, portal hypertension, or pregnancy[8,9]. When no etiologic or predisposing factor has been found, it is considered primary or idiopathic. The proportion of primary patients continues to decline due to increased awareness of predisposing disorders and a growing ability to diagnose technique[4]. As we were able to rule out any coagulation factor deficiency or other risks that could be the cause, we identified the diagnosis for idiopathic MVT.

Alander et al[10] reported the first case of MVT after renal transplantation in 1974. Due to the hypercoagulable state, the patient developed an iliofemoral venous thrombosis 1 mo after transplantation, worsened 8 mo later, and eventually died. Another case with sudden abdominal pain 10 years after successful renal transplan

Despite advances in treating thromboembolic disease over the past 40 years, acute MVT has an average 30 d mortality of up to 32.1% in severe cases[15]. Management for MVT includes surgery, anticoagulation and supportive treatment. When exploratory laparotomy is performed in the acute stage, the boundary between ischemic bowel and viable bowel is often diffuse. Segments of nonviable bowel are resected and areas of bowel with questionable viability are left for this patient. This more conservative strategy is favored over aggressive resection because of the long-term risks associated with short bowel syndrome. However, this also increases the risk of anastomotic leakage, especially together with the application of methylprednisolone. The contradictory treatment forced us to reduce the dose for the further treatment of anastomotic fistula. Fortunately, the graft showed excellent renal function without episodes of graft rejection.

Systemic anticoagulation as the first-line therapy in MVT should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is made[3]. Anticoagulation can effectively prevent thrombosis, recanalize occluded veins, and improve intestinal reperfusion. There is sufficient time for venous collateral vessels to develop when the thrombus evolves slowly, and the risk of bowel infarction can be decreased. Low molecular weight heparin is preferable over unfractionated heparin due to its better safety profile, ease of administration, and not requiring regular laboratory monitoring. For long-term management, anticoagulation with warfarin with a targeted international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is the standard of care. Although most researchers recommend maintaining anticoagulation therapy for at least 6 mo after diagnosis to prevent the recurrence of the thrombosis, its benefit is still questioned in some reports[16].

Despite its infrequency, idiopathic acute MVT after renal transplantation should be considered seriously. An accurate diagnosis and timely surgical treatment are important to improve a patient’s survival rate and conserve as much of the bowel as possible. Bleeding and anastomotic fistula during treatment need to be treated with caution because of grafts.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Maglangit SACA, Parajuli S S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Bala M, Kashuk J, Moore EE, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Gomes CA, Ben-Ishay O, Rubinstein C, Balogh ZJ, Civil I, Coccolini F, Leppaniemi A, Peitzman A, Ansaloni L, Sugrue M, Sartelli M, Di Saverio S, Fraga GP, Catena F. Acute mesenteric ischemia: guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singal AK, Kamath PS, Tefferi A. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gross PL, Weitz JI. New anticoagulants for treatment of venous thromboembolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:380-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1683-1688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kumar S, Kamath PS. Acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis: one disease or two? Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1299-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jiang Y, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang W. Diagnostic accuracy of deep vein thrombosis is increased by analysis using combined optimal cut-off values of postoperative plasma D-dimer levels. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:1716-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Duran R, Denys AL, Letovanec I, Meuli RA, Schmidt S. Multidetector CT features of mesenteric vein thrombosis. Radiographics. 2012;32:1503-1522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hmoud B, Singal AK, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Harnik IG, Brandt LJ. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Vasc Med. 2010;15:407-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alander JT, Kaartinen I, Laakso A, Pätilä T, Spillmann T, Tuchin VV, Venermo M, Välisuo P. A review of indocyanine green fluorescent imaging in surgery. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2012;2012:940585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 682] [Cited by in RCA: 878] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hauser AC, Pabinger-Fasching I, Quehenberger P, Kettenbach J, Hörl WH. A patient with sudden abdominal pain 10 years after successful renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1021-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kerlin BA, Ayoob R, Smoyer WE. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of nephrotic syndrome-associated thromboembolic disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:513-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pham PT, Peng A, Wilkinson AH, Gritsch HA, Lassman C, Pham PC, Danovitch GM. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:844-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Previtali E, Bucciarelli P, Passamonti SM, Martinelli I. Risk factors for venous and arterial thrombosis. Blood Transfus. 2011;9:120-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schoots IG, Koffeman GI, Legemate DA, Levi M, van Gulik TM. Systematic review of survival after acute mesenteric ischaemia according to disease aetiology. Br J Surg. 2004;91:17-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van der Hulle T, Tan M, den Exter PL, van Roosmalen MJ, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom J, Huisman MV, Klok FA. Recurrence risk after anticoagulant treatment of limited duration for late, second venous thromboembolism. Haematologica. 2015;100:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |