Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9847

Peer-review started: June 12, 2021

First decision: June 30, 2021

Revised: July 23, 2021

Accepted: September 23, 2021

Article in press: September 23, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 150 Days and 15.7 Hours

Adenomatous polyposis syndromes (APS) patients with ileal pouch anal anast

To assess clinical, endoscopic and histologic response to various treatment modalities employed in the therapy of pouch related disorders.

APS patients who underwent IPAA between 1987-2019 were followed every 6-12 mo and pouch-related symptoms were recorded at every visit. Lower endoscopy was performed annually, recording features of the pouch, cuff and terminal ileum. A dedicated gastrointestinal pathologist reviewed biopsies for signs and severity of inflammation. At current study, files were retrospectively reviewed for initiation and response to various treatment modalities between 2015-2019. Therapies included dietary modifications, probiotics, loperamide, antibiotics, bismuth subsalicylate, mebeverine hydrochloride, 5-aminosalicylic acid comp

Thirty-three APS patients after IPAA were identified. Before treatment, 16 patients (48.4%) suffered from abdominal pain and 3 (9.1%) from bloody stools. Mean number of daily bowel movement was 10.3. Only 4 patients (12.1%) had a PDAI ≥ 7. Mean baseline PDAI was 2.5 ± 2.3. Overall, intervention was associated with symptomatic relief, mainly decreasing abdominal pain (from 48.4% to 27.2% of patients, P = 0.016). Daily bowel movements decreased from a mean of 10.3 to 9.3 (P = 0.003). Mean overall and clinical PDAI scores decreased from 2.58 to 1.94 (P = 0.016) and from 1.3 to 0.87 (P = 0.004), respectively. Analyzing each treatment modality separately, we observed that dietary modifications decreased abdominal pain (from 41.9% of patients to 19.35%, P = 0.016), daily bowel movements (from 10.5 to 9.3, P = 0.003), overall PDAI (from 2.46 to 2.03, P = 0.04) and clinical PDAI (1.33 to 0.86, P = 0.004). Probiotics effectively decreased daily bowel movements (from 10.2 to 8.8, P = 0.007), overall and clinical PDAI (from 2.9 to 2.1 and from 1.38 to 0.8, P = 0.032 and 0.01, respectively). While other therapies had minimal or no effects. No significant changes in endoscopic or histologic scores were seen with any therapy.

APS patients benefit from dietary modifications and probiotics that improve their pouch-related symptoms but respond minimally to anti-inflammatory and antibiotic treatments. These results suggest a functional rather than inflammatory disorder.

Core Tip: We present our results of a cohort of 33 adenomatous polyposis syndromes patients who underwent ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery and developed pouch related symptoms during their follow up. We evaluated their response to treatment modalities taken from the world of ulcerative colitis patients, and irritable bowel disease patients. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatory modalities had minimal effect on outcome. Dietary modifications and probiotics seem to confer the greatest benefit for pouch-related symptoms. No therapy had a significant impact on endoscopic or histologic findings.

- Citation: Gilad O, Rosner G, Brazowski E, Kariv R, Gluck N, Strul H. Management of pouch related symptoms in patients who underwent ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery for adenomatous polyposis. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9847-9856

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9847.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9847

Total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) is performed in adenomatous polyposis syndromes (APS) to prevent colorectal cancer[1,2]. IPAA is performed most commonly in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients[1,3]. Pouchitis is an inflammatory complication of the ileal pouch primarily in UC patients, consisting of clinical symptoms together with endoscopic and histologic signs of inflammation that are graded by the pouchitis disease activity index (PDAI)[4]. Data regarding management of pouchitis originates primarily from UC studies as the prevalence of pouchitis in APS patients is considered low[5] (although a recent study has demo

Patients who present with pouch-related symptoms but without endoscopic or histologic evidence of inflammation can be defined as irritable pouch syndrome (IPS), which is a functional disorder and a diagnosis of exclusion[7]. There are currently no clear guidelines for the management of IPS, and treatment relies mainly on approaches used in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)[7,8].

Our recently published study explored the prevalence of IPS or pouchitis in a cohort consisting purely of APS patients. While only 13.7% of our cohort presented with overt pouchitis, a much higher proportion of patients suffered from IPS symptoms including abdominal pain, loose stools, nocturnal fecal seepage and increased frequency[9]. Younger age and an IPAA procedure without diverting stoma (1-step) were associated with better clinical outcomes[9].

Since data regarding management of pouch-related disorders in APS patients is scarce, we examined the effect of different treatment modalities on the clinical, endoscopic and histologic outcome of a cohort consisting purely of APS patients who underwent IPAA.

Our original study was a prospective observational, longitudinal cohort study performed at the hereditary cancer clinic in a tertiary medical center between the years 2015-2019[9]. Briefly, APS patients who underwent IPAA were followed every 6-12 mo and pouch-related symptoms were recorded at every visit. Lower endoscopy was performed annually, recording features of the pouch, cuff and terminal ileum. A dedicated gastrointestinal pathologist reviewed biopsies for signs and severity of inflammation. Clinical, endoscopic and histologic findings were used to calculate PDAI. Patients with a score of ≥ 7 were considered to have pouchitis.

In the current study we retrospectively examined clinic and endoscopy files of our APS patients-cohort for medical interventions addressing pouch-related symptoms. Since there are currently no evidence-based data to guide management of neither IPS nor pouchitis in APS patients, physicians administered therapies as best they saw fit and management was extrapolated from management of irritable bowel disease and UC-related pouchitis. Therapies included dietary modifications (We advised our patients to switch to a dietary regimen that is low in poorly digested carbohydrates and low in fiber, as fermentation of dietary carbohydrates or fiber by small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in the pouch can cause increased stool frequency and bloating. We also advised to avoid meals prior to bedtime), probiotics (bifidobacterium, lactobacillus, and streptococcus), loperamide, antibiotics (ciprofloxacin and metronidazole or tinidazole), bismuth subsalicylate, mebeverine hydrochloride, 5-ASA compounds and topical rectal steroids. We documented pre- and posttreatment symptoms reported by patients at their clinic visits. Effects on number of daily bowel movements (DBM), abdominal pain and rectal bleeding were noted. We compared the PDAI and its clinical, endoscopic and histologic subscores before and after treatment, and examined the effect of each treatment modality on these scores. PDAI was calculated according to symptoms, histology and endoscopic findings found prior to therapy, and after therapy was initiated. While PDAI is a score to grade pouchitis and not IPS, PDAI subscores allow quantification of symptoms burden and endoscopic and histologic signs of inflammation even in patients without frank pouchitis, thus providing a tool to measure changes in response to different treatment modalities. The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and categorical variables as proportions. Change of variables before and after therapy was assessed using Wilcoxon signed rank test for continuous variables and using McNemar’s test for categorical variables. Association was evaluated using the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. SPSS software was used for all analyses (IBM version 25, 2017).

Thirty-three APS patients that underwent IPAA between the years 1987 to 2019 were treated for pouch-related symptoms during the years 2015-2019. Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Mean age at surgery and at study enrollment was 33.2 and 47.6, respectively. Mean time from surgery to enrollment was 14.4 years. All patients underwent creation of a J-pouch in an open surgical approach and stapled anastomosis. Nine patients (27.2%) underwent a single stage procedure, and the other 24 patients underwent a 2 stage procedure with a protective ileostomy that was closed after a few months.

| Characteristics | Data |

| Sex, male | 14 (42.4) |

| Mean age at surgery, years (mean ± SD) | 33.2 ± 11.2 |

| Ethnicity, Ashkenazi | 11 (33.3) |

| Genetic diagnosis | |

| FAP | 26 (78.7) |

| Attenuated FAP | 3 (9.1) |

| Polymerase proofreading polyposis | 1 (3) |

| MUTYH | 3 (9.1) |

| mean age at study enrollment, years (mean ± SD) | 47.6 ± 12.8 |

| mean time from surgery to enrollment, years (mean ± SD) | 14.4 ± 6.9 |

| mean time from pre-treatment endoscopy to clinic visit, months (mean ± SD) | 9.6 ± 8.7 |

| mean time from clinic visit to post-treatment endoscopy, months (mean ± SD) | 6.5 ± 6.8 |

| Patients undergoing single stage pouch surgery | 9 (27.2) |

| Treatments | |

| Diet | 30 (90.9) |

| Probiotics | 21 (63.6) |

| Loperamide | 14 (42.4) |

| Bismuth | 6 (18.1) |

| Mebeverine | 6 (18.1) |

| Antibiotics | 9 (27.2) |

| 5-ASA | 5 (15.1) |

| Topical steroids | 1 (3.0) |

| Patients with desmoid tumor | 13 (39.4) |

Before treatment, 16 patients (48.4%) suffered from abdominal pain and 3 (9.1%) from bloody stools. Mean number of DBM was 10.3. Only 4 patients (12.1%) had a PDAI ≥ 7. Mean baseline PDAI was 2.5 ± 2.3.

Thirty patients (90.9%) were treated with dietary modifications and 21 (63.6%) with probiotics. Pharmacological therapies included loperamide in 14 (42.4%) patients, antibiotics in 9 (27.2%), bismuth subsalicylate in 6 (18.1%), mebeverine in 6 (18.1%), 5-ASA compounds in 5 (15.1%) and topical rectal steroids in one case (3.1%). Patients were treated with a mean of 2.8 ± 1.2 modalities.

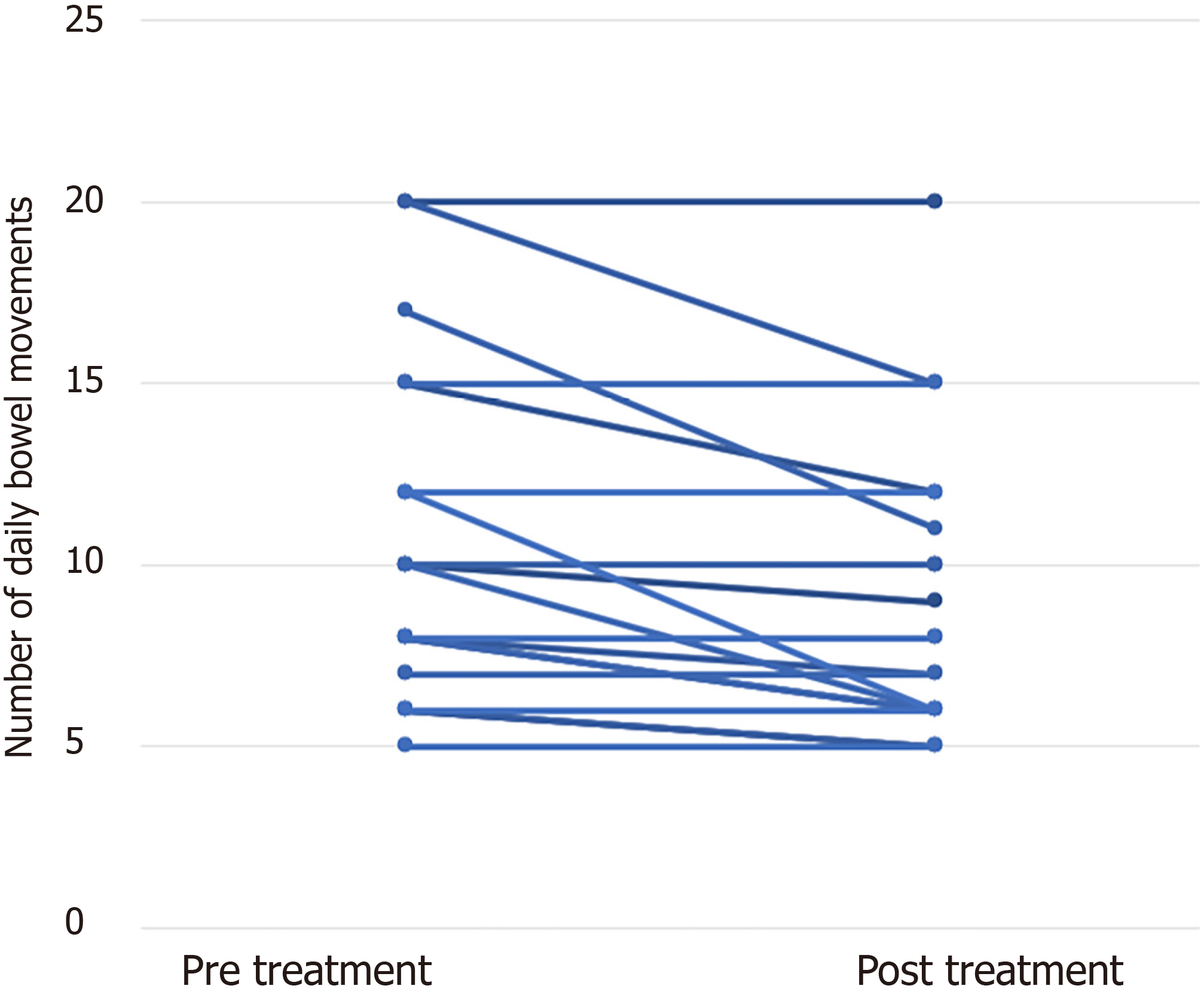

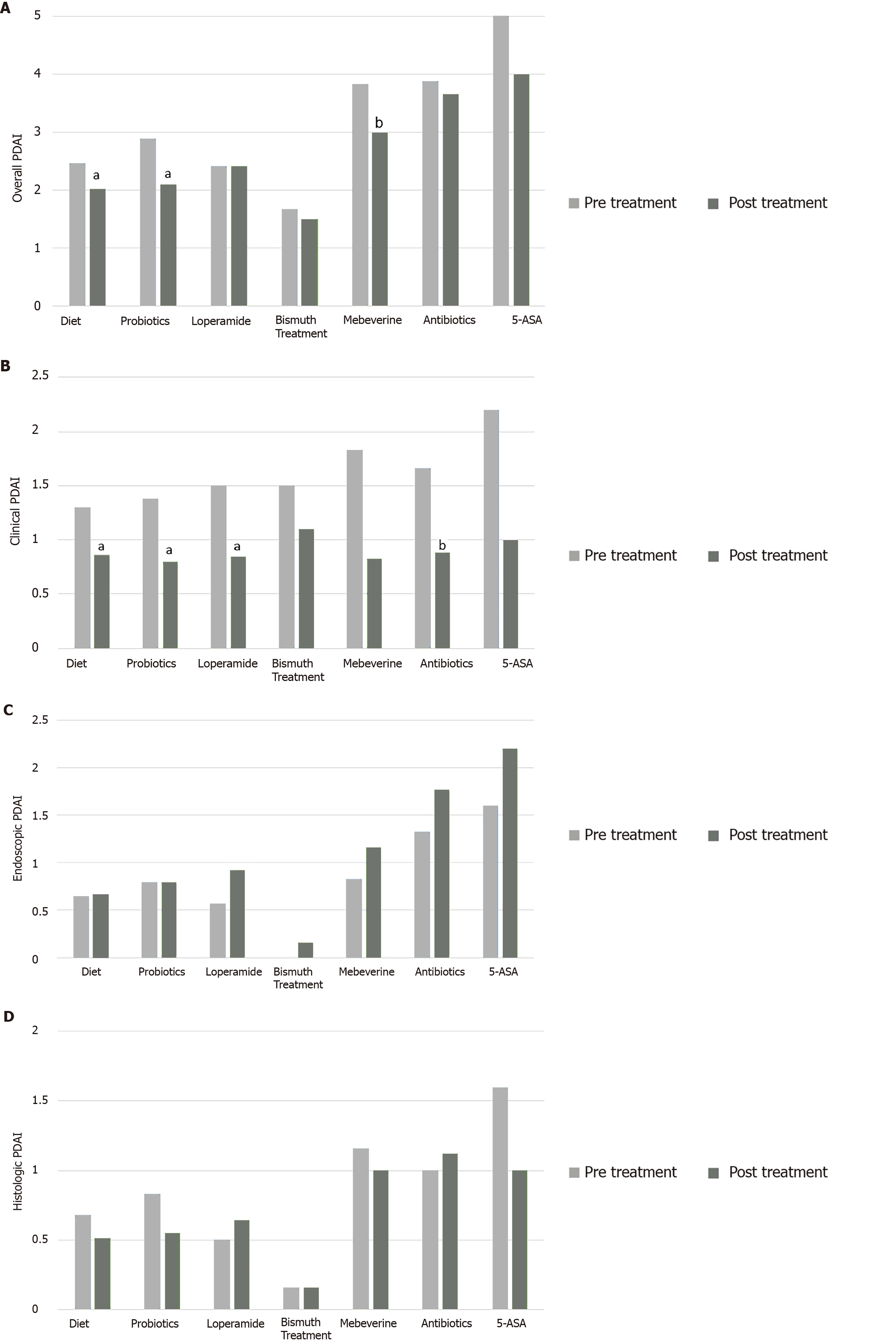

Overall, the use of any intervention was associated with symptomatic relief (Table 2). The most striking effect was on abdominal pain (48.4% compared to 27.2% after treatment, P = 0.016). DBM decreased from a mean of 10.3 to 9.3 (P = 0.003). The main drivers of this statistically significant change were eleven patients (33.3%) who had a mean reduction of 3.1 DBM, while all other patients experienced no change in bowel habits (Figure 2). These results were also reflected in PDAI scores: mean overall PDAI and clinical PDAI subscore both decreased with therapy [from 2.58 to 1.94 (P = 0.016) and from 1.3 to 0.87 (P = 0.004), respectively]. Endoscopic or histologic PDAI subscores did not change significantly [pre/post treatment mean values of 0.65/0.6 (P = 0.86), and 0.76/0.46 (P = 0.60), respectively].

| Treatment | All (n = 33) | Diet (n = 30) | Probiotics (n = 21) | Loperamide (n = 14) | Bismuth (n = 6) | Antibiotics (n = 9) | Mebeverine (n = 6) | 5-ASA (n = 5) | ||||||||

| Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | Data | P value | |

| Mean BM | 0.003a | 0.003a | 0.007a | 0.027a | 0.18 | 0.042a | 0.1 | 0.066 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 10.3 ± 4.3 | 10.5 ± 4.4 | 10.2 ± 3.8 | 9.4 ± 3.2 | 9.0 ± 3.3 | 9.7 ± 5.1 | 11.8 ± 5.4 | 11.2 ± 5.01 | ||||||||

| After treatment | 9.3 ± 4.1 | 9.3 ± 4.2 | 8.8 ± 3.2 | 8.14 ± 2.47 | 8.3 ± 2.4 | 7.6 ± 3.4 | 10.0 ± 5.3 | 8.6 ± 3.9 | ||||||||

| Patients with bloody stools | 0.62 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 3 (9.1) | 3 (10) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 1 (16.67) | 1 (20) | ||||||||

| After treatment | 2 (6.06) | 2 (6.67) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Patients with abdominal pain | 0.016a | 0.016a | 0.12 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 16 (48.4) | 13 (43.3) | 11 (52.3) | 7 (50) | 4 (66.6) | 4 (44.4) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (40) | ||||||||

| After treatment | 9 (27.2) | 6 (20) | 7 (33.3) | 4 (28.5) | 3 (50) | 2 (22.2) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (20) | ||||||||

| Mean clinical PDAI | 0.004a | 0.004a | 0.01a | 0.024a | 0.15 | 0.066 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.38 ± 1.11 | 1.5 ± 1.28 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.67 ± 1.2 | 1.83 ± 1.32 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | ||||||||

| After treatment | 0.87 ± 0.89 | 0.86 ± 0.93 | 0.80 ± 0.74 | 0.85 ± 0.77 | 1.1 ± 0.75 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.83 ± 0.75 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | ||||||||

| Mean endoscopic PDAI | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.059 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.45 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 0.65 ± 0.97 | 0.65 ± 1.0 | 0.80 ± 1.12 | 0.57 ± 1.08 | 0 | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 0.83 ± 1.16 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | ||||||||

| After treatment | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.66 ± 1.15 | 0.80 ± 1.32 | 0.92 ± 1.26 | 0.16 ± 0.40 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.16 ± 1.16 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | ||||||||

| Mean histologic PDAI | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.31 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 0.76 ± 1.0 | 0.68 ± 1.04 | 0.83 ± 1.04 | 0.5 ± 0.84 | 0.16 ± 0.40 | 1.0 ± 1.06 | 1.16 ± 0.98 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | ||||||||

| After treatment | 0.46 ± 0.76 | 0.51 ± 0.78 | 0.55 ± 0.82 | 0.64 ± 0.92 | 0.16 ± 0.40 | 1.1 ± 0.99 | 1.0 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | ||||||||

| Mean overall PDAI | 0.01a | 0.04a | 0.032a | 1 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.059 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 2.51 ± 2.38 | 2.46 ± 2.48 | 2.9 ± 2.54 | 2.42 ± 2.44 | 1.67 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 3.83 ± 2.78 | 5.4 ± 2.7 | ||||||||

| After treatment | 1.93 ± 2.01 | 2.03 ± 2.09 | 2.1 ± 2.2 | 2.42 ± 2.37 | 1.50 ± 1.04 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 4.0 ± 2.9 | ||||||||

Isolating the effect of each treatment modality revealed similar trends (Table 2 and Figure 1). Dietary modifications decreased abdominal pain (from 41.9% of patients to 19.35%, P = 0.016), DBM (from 10.5 to 9.3, P = 0.003) and both overall and clinical PDAI (from 2.46 to 2.03 and 1.33 to 0.86, P = 0.04 and 0.004, respectively) but did not affect endoscopic or histologic outcomes. Probiotics also decreased DBM (from 10.2 to 8.8, P = 0.007), overall and clinical PDAI (from 2.9 to 2.1 and from 1.38 to 0.8, P = 0.032 and 0.01, respectively). Loperamide decreased DBM (from 9.4 to 8.1, P = 0.027) and clinical PDAI (1.5 to 0.85, P = 0.024) but not endoscopic, histologic, or overall PDAI. Antibiotics decreased DBM (9.7 to 7.6, P = 0.042) but were not associated with significant changes in overall PDAI or any of its subscores. Bismuth subsalicylate, mebeverine and 5-ASA did not affect symptoms or PDAI. Since topical steroids were used in one patient, statistical analysis of their individual effects was uninformative.

Of the four patients who had overt pouchitis (PDAI ≥ 7), three were treated with antibiotics, 3 with 5-ASA agents and one with topical steroids. A trend toward decreases in overall and clinical PDAI was noted, while not statistically significant in this small group. No changes in endoscopic or histologic PDAI subscores were seen.

Analysis of outcomes by gender revealed minor differences. No significant reduction in abdominal pain or rectal bleeding was seen when analyzing either of the sexes separately. Both male and female patients experienced decrease in DBM [from 11.07 to 9.7 (P = 0.038) and from 9.8 to 8.9 (P = 0.027), respectively]. While female patients had a significant decrease in clinical PDAI which was not apparent in male patients (1.31 to 0.89, P = 0.02), males were the only subgroup to show a decrease in endoscopic PDAI subscore (0.84 to 0.35, P = 0.034).

Younger age at surgery (< 40 compared to ≥ 40) was associated with better treatment outcomes. Younger patients had a mild decrease in number of bowel movements (from 9.8 to 8.8, P = 0.011), overall and clinical PDAI scores [2.34 to 1.86 (P = 0.04), 1.26 to 1.0 (P = 0.01), respectively), compared to no significant change in older patients [DBM decreased from 11.5 to 10.3 (P = 0.10), overall PDAI changed from 2.9 to 2.1 (P = 0.15) and clinical PDAI from 1.4 to 0.6 (P = 0.06)]. No significant reduction in abdominal pain or rectal bleeding was seen when analyzing either group separately.

Eleven patients (33.3%) had a documented post-operative complication including 6 patients with post-operative small bowel obstruction, 4 with anastomotic leakage, 2 with fistula and 1 with wound infection. Patients who had post-operative complications were somewhat less responsive to treatment. These patients had no significant reduction in DBM or clinical PDAI score (10.45 to 10.0, P = 0.10 and 0.72 to 0.54, P = 0.15, respectively), while those who did not suffer post-operative complications had a reduction of DBM from 10.3 to 8.9 (P = 0.01) and clinical PDAI from 1.6 to 1.04 (P = 0.01). The pre-treatment clinical PDAI was the only baseline parameter that differed between the subgroups (0.72 and 1.6, P = 0.03). Patients with post-operative complications had a better clinical score at baseline. Therefore, obtaining significant improvement may have been more challenging.

Next, we analyzed the association of surgical approach (with or without diverting stoma) with outcomes. No significant reduction in abdominal pain or rectal bleeding was seen when analyzing either surgical approach separately. Baseline PDAI scores were similar. While both surgical approaches had a decrease in DBM [from 10.2 to 8.3 in 1 step procedure (P = 0.04) and from 10.6 to 9.8 in 2 step procedure (P = 0.02)] and in clinical PDAI [from 1.6 to 1.0 in 1 step (P = 0.034) and from 1.21 to 0.86 in 2 step procedure (P = 0.03)], only the 2 step approach had a significant reduction in overall PDAI (from 2.47 to 1.73, P = 0.01).

Our study on APS patients analyzed the response of pouch-related disorders to various treatment modalities. Current data relies almost exclusively on UC patients and consists of small randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) with only a few dozen patients[1,4]. Furthermore, there are virtually no studies regarding the management of IPS in neither UC nor APS patients. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the outcome of therapy of pouch-related disorders in a cohort consisting purely of APS patients.

Our data demonstrates that dietary modifications and administration of probiotics have the highest impact on our APS study population, reducing symptoms and thus also clinical and overall PDAI scores. Several small studies have evaluated the effect of diet on pouch function. Low fermentable oligo-di-monosaccharides and polyols diet was found to reduce stool frequency, but only in patients who did not have pouchitis[10]. Dietary fiber found in fruits and vegetables is reportedly associated with pouch-related symptoms, and is thus generally avoided by patients[11]. Since bacterial dysbiosis is hypothesized to be one of the etiologies of pouchitis, probiotics have been used for both treatment and prophylaxis of pouchitis[1,4]. There are no studies on the role of probiotics in IPS, however many have explored the utilization of probiotics in IBS patients. Although many of these studies have been criticized for flawed design, namely small sample size, under-powering and inadequate data to determine efficacy and adverse events, there have been some favorable results mainly regarding global symptom reduction, bloating and flatulence[12]. Our findings support a dominant role for probiotics and especially diet in the management of pouch-related symptoms in APS patients. The response to these treatment modalities in our cohort supports the notion that the pathophysiology of these symptoms is less related to an inflammatory response, but rather to a functional disorder.

Supporting this notion, no change was seen in overall PDAI or any of its components in patients treated with antibiotics (besides a small decrease in DBM), 5-ASA agents or topical steroids. Furthermore, our data demonstrate ineffective reduction of endoscopic and histologic signs of inflammation even in patients with overt pouchitis (PDAI score ≥ 7), and although this group was very small, we hypothesize that that fact that this subgroup with overt pouchitis did not show any significant change after anti –inflammatory or antibiotic treatment may indicate the fact that the basic pathophysiologic changes of pouch related symptoms in APS patients is not inflammatory at its basis. IPS is characterized by visceral hypersensitivity[13]. Therefore it is not surprising that anti-inflammatory modalities had little effect in our cohort. In contrast, antibiotics are considered first line therapy for acute pouchitis in UC patients[1,4], while 5-ASA agents and topical steroids have also proved to be effective in improving clinical, endoscopic and histologic signs of pouchitis[14-16].

Symptomatic therapies in our study such as mebeverine and bismuth subsalicylate did not produce significant symptomatic relief nor did they decrease any component of the PDAI score, although loperamide decreased the number of DBM as expected[17]. A small RCT examining the effect of bismuth carbomer enemas for chronic active pouchitis has previously failed to show any significant improvement compared to placebo[18]. Mebeverine has not been examined as a symptomatic relief agent for pouchitis, but rather in the treatment of IBS. A large systematic review which included 555 IBS patients treated with mebeverine did not show overall improvement or relief of abdominal pain[19]. It is not surprising to observe similar results for APS patients in our study.

Our study has several limitations. While originally most data were collected prospectively, the analysis of different interventions were not in the original study design and data were collected retrospectively. Therefore, there is no placebo control group. Patients were also treated with several treatment modalities (average being almost 3 per patient), therefore in some cases it was not possible to separate the effects of individual therapies from one another. Some treatments were only administered to a small number of patients. The results of the individual therapies should therefore be approached with caution as we were unable to completely separate the different treatments modalities from one another. This may have caused confounding of the results.

Nevertheless, a major strength of our study is that it concentrates on an APS population that tends to be underrepresented in other pouch-related studies, and although the cohort is small compared to UC cohorts, it still provides valuable information due to the rarity of polyposis syndromes.

In conclusion, our study shows a minimal if any response to conventional anti-inflammatory and antibiotic treatments in a cohort of APS patients. No therapy had a significant impact on endoscopic or histologic findings. Dietary modifications and probiotic supplementation seem to confer the greatest benefit for pouch-related symptoms in our study cohort. Their availability and minimal side effects should prompt physicians to consider their use as first line therapy in APS patients. Further prospective trials are warranted.

Total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis is performed in adenomatous polyposis syndromes patients to prevent the development of colon cancer. Pouch surgery has a major impact on quality of life - causing increased number of bowel movements and abdominal pain.

Unlike inflammatory bowel disease patients, data regarding response to different treatment modalities targeting pouch-related disorders in adenomatous polyposis patients is scarce.

This study aimed to assess clinical, endoscopic and histologic response to various treatment modalities used in the therapy of pouch related disorders.

Files of adenomatous polyposis patients followed prospectively were retrospectively reviewed for initiation of various therapies. Symptoms and endoscopic and histologic signs of pouch inflammation before and after treatment were assessed. Pouchitis disease activity index and its subscores were calculated.

Overall, intervention was associated with symptomatic relief, mainly decreasing abdominal pain. Daily bowel movements decreased from a mean of 10.3 to 9.3. Mean overall and clinical PDAI scores decreased from 2.58 to 1.94 and from 1.3 to 0.87, respectively. Dietary modifications decreased abdominal pain. Probiotics effectively decreased daily bowel movements, overall and clinical PDAI. While other therapies had minimal or no effects.

Adenomatous polyposis patients benefit from dietary modifications and probiotics that improve their pouch-related symptoms but respond minimally to anti-inflammatory and antibiotic treatments

Adenomatous polyposis patients respond differently to pouch related symptoms than ulcerative colitis patients. Dietary modification and probiotics should be considered first line treatment of pouch related disorders in this population.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: The Israeli Society of Gastroenterology and Liver Disease.

Specialty type: Genetics and Heredity

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D, D, D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Ahmed M, Brisinda G, Bustamante-Lopez LA, Christodoulou DK, De U, Mankaney GN, M'Koma A, Zhou W S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Dalal RL, Shen B, Schwartz DA. Management of Pouchitis and Other Common Complications of the Pouch. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:989-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | da Luz Moreira A, Church JM, Burke CA. The evolution of prophylactic colorectal surgery for familial adenomatous polyposis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1481-1486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cima RR, Pemberton JH. Medical and surgical management of chronic ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg. 2005;140:300-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and management of pouchitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1636-1650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lovegrove RE, Tilney HS, Heriot AG, von Roon AC, Athanasiou T, Church J, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. A comparison of adverse events and functional outcomes after restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis and ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1293-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Quinn KP, Lightner AL, Pendegraft RS, Enders FT, Boardman LA, Raffals LE. Pouchitis Is a Common Complication in Patients With Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Following Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1296-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shen B, Achkar JP, Lashner BA, Ormsby AH, Brzezinski A, Soffer EE, Remzi FH, Bevins CL, Fazio VW. Irritable pouch syndrome: a new category of diagnosis for symptomatic patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:972-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zezos P, Saibil F. Inflammatory pouch disease: The spectrum of pouchitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8739-8752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gilad O, Gluck N, Brazowski E, Kariv R, Rosner G, Strul H. Determinants of Pouch-Related Symptoms, a Common Outcome of Patients With Adenomatous Polyposis Undergoing Ileoanal Pouch Surgery. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2020;11:e00245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Croagh C, Shepherd SJ, Berryman M, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Pilot study on the effect of reducing dietary FODMAP intake on bowel function in patients without a colon. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1522-1528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ardalan ZS, Yao CK, Sparrow MP, Gibson PR. Review article: the impact of diet on ileoanal pouch function and on the pathogenesis of pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1323-1340. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Chey WD. SYMPOSIUM REPORT: An Evidence-Based Approach to IBS and CIC: Applying New Advances to Daily Practice: A Review of an Adjunct Clinical Symposium of the American College of Gastroenterology Meeting October 16, 2016 • Las Vegas, Nevada. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13:1-16. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shen B, Sanmiguel C, Bennett AE, Lian L, Larive B, Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Soffer EE. Irritable pouch syndrome is characterized by visceral hypersensitivity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:994-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Miglioli M, Barbara L, Di Febo G, Gozzetti G, Lauri A, Paganelli GM, Poggioli G, Santucci R. Topical administration of 5-aminosalicylic acid: a therapeutic proposal for the treatment of pouchitis. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Lopez R, Brzezinski A, Oikonomou I, Sherman KK, Lashner BA. Combined ciprofloxacin and tinidazole therapy in the treatment of chronic refractory pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:498-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sambuelli A, Boerr L, Negreira S, Gil A, Camartino G, Huernos S, Kogan Z, Cabanne A, Graziano A, Peredo H, Doldán I, Gonzalez O, Sugai E, Lumi M, Bai JC. Budesonide enema in pouchitis--a double-blind, double-dummy, controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trinkley KE, Nahata MC. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2011;36:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, Wolff BG, Carpenter HA, Zinsmeister AR, Metzger PP. Bismuth carbomer foam enemas for active chronic pouchitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:1041-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Darvish-Damavandi M, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A systematic review of efficacy and tolerability of mebeverine in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |