Published online Nov 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9835

Peer-review started: May 13, 2021

First decision: July 4, 2021

Revised: July 18, 2021

Accepted: September 1, 2021

Article in press: September 1, 2021

Published online: November 16, 2021

Processing time: 180 Days and 10.2 Hours

Although endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) has a positive therapeutic effect on biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), some patients still have little relief after EST, which implies that other functional abdominal pain may also be present with biliary-type SOD and interfere with the diagnosis and treatment of it.

To retrospectively assess EST as a treatment for biliary-type SOD and analyze the importance of functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) in guiding endoscopic treatment of SOD.

Clinical data of 79 patients with biliary-type SOD (type I and type II) treated with EST at Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University from January 2014 to January 2019 were retrospectively collected to evaluate the clinical therapeutic effect of EST. The significance of relationship between FGID and biliary-type SOD was analyzed.

Seventy-nine patients with biliary-type SOD received EST, including 29 type 1 patients and 50 type 2 patients. The verbal rating scale-5 (VRS-5) scores before EST were all 3 or 4 points, and the scores decreased after EST; the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). After EST, the serum indexes of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase and total bilirubin in biliary-type SOD were significantly lower than before (P < 0.05). After EST, 67 (84.8%) and 8 (10.1%) of the 79 patients with biliary-type SOD had obviously effective (VRS-5 = 0 points) and effective treatment (VRS-5 = 1-2 points), with an overall effectiveness rate of 94.9% (75/79). There was no difference in VRS-5 scores between biliary-type SOD patients with or without FGID before EST (P > 0.05). Of 12 biliary-type SOD (with FGID) patients, 11 had abdominal pain after EST; of 67 biliary-type SOD (without FGID) patients, 0 had abdominal pain after EST. The difference was statistically significant (P <0.05). The 11 biliary-type SOD (with FGID) patients with recurrence of symptoms, the recurrence time was about half a year after the EST, and the symptoms were significantly relieved after regular medical treatment. There were 4 cases of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (5.1%), and no cholangitis, bleeding or perforation occurred. Patients were followed up for 1 year to 5 years after EST, with an average follow-up time of 2.34 years, and there were no long-term adverse events such as sphincter of Oddi restenosis or cholangitis caused by intestinal bile reflux during the follow-up.

EST is a safe and effective treatment for SOD. For patients with type I and II SOD combined with FGID, single EST or medical treatment has limited efficacy. It is recommended that EST and medicine be combined to improve the cure rate of such patients.

Core Tip: This article retrospectively analyzed the effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy on biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), which increased the pain score system and the breakdown of SOD types. At the same time, functional gastrointestinal disorder and SOD are both functional diseases and often co-occur, thus affecting the endoscopic treatment of SOD. For this type of patient, this article gives appropriate guidance and treatment opinions.

- Citation: Ren LK, Cai ZY, Ran X, Yang NH, Li XZ, Liu H, Wu CW, Zeng WY, Han M. Evaluating the efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy on biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: A retrospective clinical trial. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(32): 9835-9846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i32/9835.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9835

The sphincter of Oddi is a group of fibromuscular structures surrounding the common bile duct, pancreatic duct and common channel, which was first reported by Ruggero Oddi in 1887[1]. Biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) has two patho

This article integrates the diagnosis and treatment standards of biliary-type SOD, retrospectively analyzes the clinical data of 79 patients with type I and type II SOD treated by EST, scientifically evaluates the clinical diagnosis and treatment and analyzes the relationship of FGID and biliary-type SOD.

The clinical data of 910 patients diagnosed and treated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University from January 2014 to January 2019 were retrospectively collected (all performed by one operator). The inclusion criteria for patients with biliary-type SOD were as follows: (1) Conformed to the diagnostic criteria for biliary abdominal pain (Rome IV[11]); and (2) Had abnormal serum indexes of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin or alkaline phosphatase > 2 times the normal values documented on 2 or more occasions and/or had a dilated bile duct greater than 8 mm in diameter. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography were suspicious for bile duct stones, tumors or other biliary obstruction lesions; or (2) Pain was significantly related to defecation, postural changes and the use of antacid drugs such as proton pump inhibitors, histamine type-2 receptor antagonists, calcium or magnesium salts, etc. According to the revised Milwaukee classification[11], patients with biliary-type SOD are divided into type I and type II (excluding type III cases).

According to the above criteria, patients with type I and type II biliary-type SOD were selected, and those with cholelithiasis, benign and malignant tumors of the biliary tract, pancreatobiliary malfunction, pancreatic divisum, intrahepatic bile duct stenosis and biliary ascariasis, etc., were excluded. In total, 79 patients with biliary-type SOD were finally included in this study, including 27 males and 52 females (male:female approximately = 1:2) aged 8 to 85 years (average 58.72 ± 14.16 years).

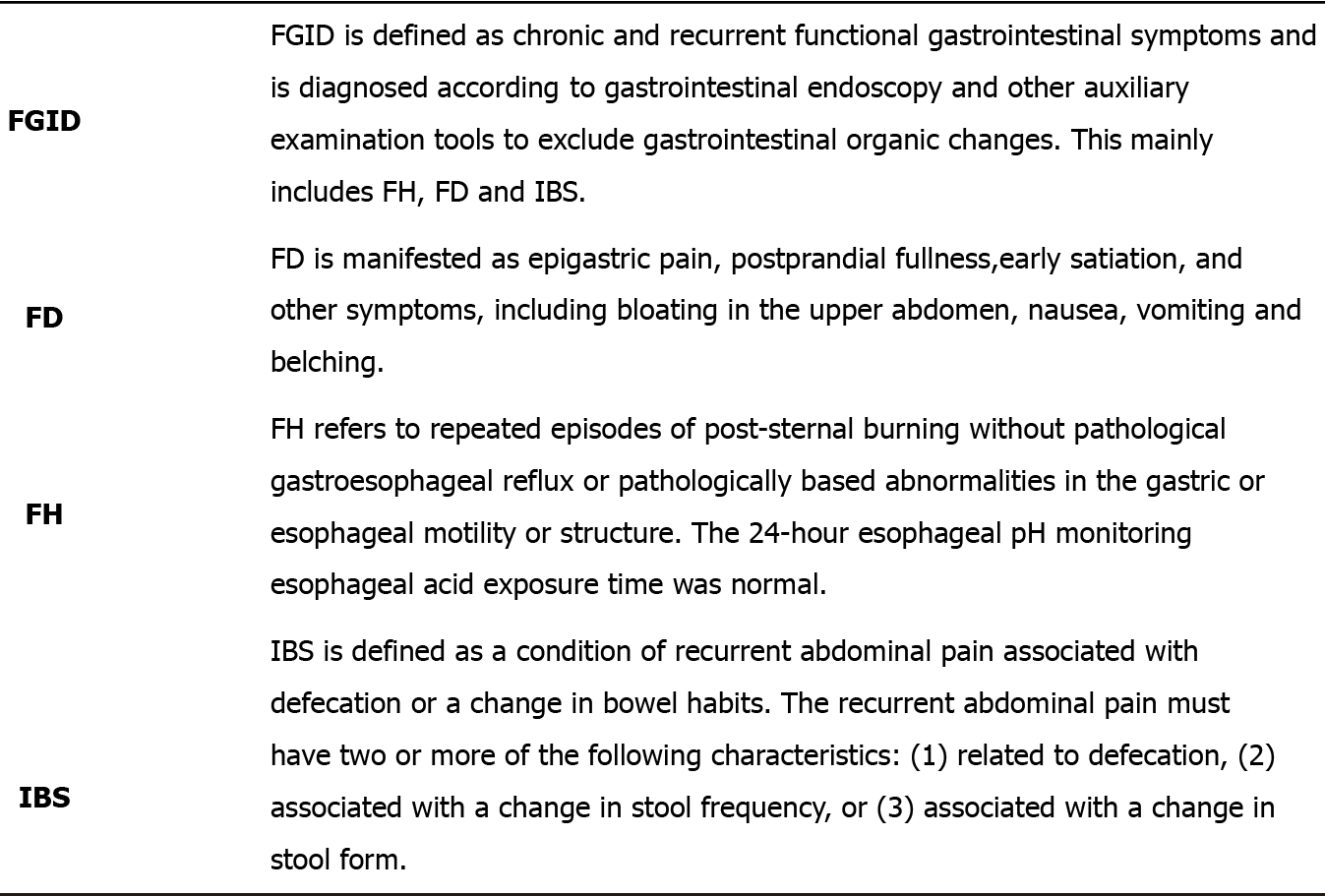

According to the impression of the endoscopist’s first visit to the patient, the gastrointestinal endoscopy and other auxiliary examination tools were used for diagnosis and in strict accordance with the diagnostic criteria of FGID of Rome IV, a total of 12 FGID patients were screened out of 79 SOD patients. Among them, combined FD, FH and IBS accounted for 5 cases, 4 cases and 3 cases, respectively. There were 29 cases of type I and 50 cases of type II biliary-type SOD. In type II patients, with elevated liver enzymes and no dilated bile ducts were divided into group Type IIa, and patients with normal liver enzymes but dilated bile ducts were divided into group Type IIb. There were 6 patients in group Type IIa and 44 patients in group Type IIb. The diagnostic criteria for FGID are shown in Figure 1. The general data of biliary-type SOD patients are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Type I, n = 29 | Type IIa, n = 6 | Type IIb, n = 44 |

| Sex (male/female) | 8/21 | 4/2 | 15/29 |

| Age [mean (SD), yr] | 59.10 ± 17.36 | 56.00 ± 19.03 | 58.84 ± 11.14 |

| With FH (n) | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| With IBS (n) | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| With FD (n) | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| ALT [M (IQR), U/L] | 209.90 (121.55-361.39) | 170.02 (110.25-203.36) | 25.65 (16.75-66.50) |

| AST [M (IQR), U/L] | 194.66 (75.90-345.50) | 136.78 (48.81-175.61) | 28.00 (22.32-360.06) |

| TBIL [M (IQR), mg/dL] | 4.52 (3.13-8.13) | 6.09 (4.24-11.23) | 1.69 (1.15-3.12) |

| ALP [M (IQR), U/L] | 199.44 (155.73-311.78) | 354.70 (201.68-470.88) | 98.20 (78.20-117.40) |

| Bile duct diameter [M (IQR), cm] | 1.20 (1.00-1.50) | 0.80 (0.78-0.80) | 1.50 (1.10-2.00) |

According to the effect of abdominal pain symptoms on the quality of life of patients with biliary-type SOD, the Verbal Rating Scale-5 (VRS-5)[12] was used to assess the degree of abdominal pain in the patients, which was coded as 0 - 4 points according to the severity of abdominal pain. The VRS-5 score system is shown in Table 2.

| 0 points | No pain |

| 1 point | Mild pain that is tolerable with normal life and sleep |

| 2 points | Moderate pain that can interfere with proper sleep and requires analgesics |

| 3 points | Severe pain and disturbed sleep that require anesthesia and analgesics |

| 4 points | Severe pain causing severe interference with sleep accompanied by other symptoms or passive posture |

Biliary-type SOD patients with FGID were given medical therapy: patients with FD were given acid suppression and other drug treatments for gastrointestinal motility and digestion; patients with IBS were given antispasmodics, laxatives, intestinal microecological preparations and other drug treatments; and patients with FH were given symptomatic supportive therapy such as acid suppression and gastrointestinal motility treatments. All SOD patients including 12 patients with FGID who had undergone medical treatment in this test with poor symptom improvement and VRS-5 scores of 3 to 4 were given EST.

TJF260V electronic duodenoscope (Olympus Corporation), disposable radiography catheter (Olympus Corporation), three-chamber papillary sphincterotomy (Cook company), needle knife (Olympus Corporation), yellow zebra guide wire (Olympus Corporation), balloon dilatation catheter (Cook Endoscopy), stone extraction balloon (Olympus Corporation), transnasal external bile drainage tube (Olympus Corpo

After completing the preoperative examination and obtaining informed consent for ERCP, the diagnosis and treatment of ERCP began, and the preoperative evaluation and intraoperative conditions were given corresponding endoscopic treatment, in

All patients underwent EST. For patients with obvious bile duct dilatation, ERBD was performed. ENBD was performed after the operation to prevent postoperative papillary edema and post-ERCP pancreatitis. If the guide wire repeatedly entered the pancreatic duct during ERCP, then to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage may be performed depending on the situation.

If ENBD was performed after EST, the tube shall be removed within 3 d after EST according to the patient’s condition. For patients undergoing ERBD or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, the tubes fell off within 3 mo of treatment after EST in most circumstances. If the tube has not fallen off after 3 mo, it shall be taken out with ERCP for the second time.

Those who had postoperative adverse events were fasted and treated with gas

The improvement in various serum indicators in patients with biliary-type SOD was observed 1 wk after EST. All patients were followed up after EST, with a follow-up interval of 1 year to 5 years. VRS-5 scoring methods were used to evaluate the improvement in symptoms of patients after EST, with 0 being obviously effective, 1 to 2 being effective and 3 to 4 being ineffective.

Biliary-type SOD patients with FGID before EST were followed up to observe if their gastrointestinal symptoms had improved, and those with poor symptom re

Statistical analysis software 25.0 was used for data analysis. Measurement data conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± SD. Measurement data that did not conform to a normal distribution were expressed as the median (interquartile range), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze these data. Count data are expressed as a percentage (%), and Fisher’s exact probability method was used to analyze these data. Grade data were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The preoperative VRS-5 scores of 79 patients were all 3 and 4 points; among them, the symptoms of 12 patients with FGID did not receive relief with medication. All patients were given EST. The VRS-5 score of biliary-type SOD before EST was shown in Table 3. ERCP intraoperative situation was shown in Table 4.

| Biliary-type SOD | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points |

| Type I, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 |

| Type II, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 7 |

| Total, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 10 |

| Successful intubation rate | n = 79 |

| EST | 79 |

| With ENBD | 66 |

| With EPBD | 21 |

| With ERBD | 8 |

| With ERPD | 4 |

| The average CBD in cm | 1.4 (range: 1.0-1.8) |

| The average EST incision length in cm | 0.52 ± 0.16 |

Within 1 wk after endoscopic treatment, all patients’ symptoms were relieved, and the serum indexes of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were significantly lower than before (P < 0.05) (Table 5). Sixty-six patients who used ENBD during the EST were removed within 3 d after the ERCP, and the average extubation time was 2.15 ± 0.44 d. In the 12 patients who underwent ERBD and endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, all the tubes fell off within 3 mo after EST, and the average time for the tubes to fall off by itself was 37.65 ± 11.48 d. Postoperative hyperamylasemia occurred in 2 cases, and pancreatitis occurred in 4 cases (5.1%), all of which were mild and improved with conservative treatment. No postoperative cholangitis, bleeding or perforation adverse events occurred.

| Serum index1 | Biliary-type SOD | P value | |

| Pre-EST | Post-EST | ||

| ALT [M (IQR), U/L] | 70.00 (24.10-190.03) | 29.22 (18.00-58.00) | < 0.001 |

| AST [M (IQR), U/L] | 61.51 (26.08-157.79) | 30.59 (22.00-64.00) | < 0.001 |

| TBIL [M (IQR), mg/dL] | 2.98 (1.49-5.02) | 2.00 (1.14-3.03) | 0.004 |

| ALP [M (IQR), U/L] | 129.00 (91.50-220.91) | 7.60 (3.70-12.30) | < 0.001 |

The patients were followed up for 1 year to 5 years, with a median follow-up time of 2.34 years. No patients were lost to follow-up. The VRS score of SOD patients decreased significantly after EST (P < 0.05) (Tables 6-7). The 8 SOD patients with ENBD and 21 SOD patients with endoscopic papillary balloon dilation during the ERCP were either spontaneously detached or removed under ERCP within 4 mo. No postoperative adverse events such as restenosis of the sphincter of Oddi or cholangitis due to intestinal biliary reflux occurred. None of the patents underwent EST or other surgery again.

| Biliary-type SOD | Period | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | P value |

| Type I (n) | Pre-EST | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| Post-EST | 24 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Type II (n) | Pre-EST | 0 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 7 | < 0.001 |

| Post-EST | 43 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Biliary-type SOD | Period | 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | P value |

| Type IIa (n) | Pre-EST | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Post-EST | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Type IIb (n) | Pre-EST | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 7 | < 0.001 |

| Post-EST | 37 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 |

The therapeutic effect of EST on SOD is shown in Tables 8-9. There was no statistically significant difference in the overall effectiveness between the type I and type II (P = 0.291) and Type IIa and Type IIb (P = 0.317).

| Biliary-type SOD | Obviously effective | Effective | Ineffective | Total, n | Overall effectiveness, % | ||

| 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | |||

| Type I, n | 24 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 100.0 |

| Type II, n | 43 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 50 | 92.0 |

| Biliary-type SOD | Obviously effective | Effective | Ineffective | Total, n | Overall effectiveness, % | ||

| 0 points | 1 point | 2 points | 3 points | 4 points | |||

| Type IIa, n | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| Type IIb, n | 37 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 44 | 90.9 |

Of the 12 patients with biliary-type SOD combined with FGID before EST, 11 patients had abdominal pain again with digestive symptoms approximately 6 mo after EST (Table 10), including 4 cases with FH, 2 cases with IBS and 5 cases with FD. Only 1 case with FH did not show any discomfort after surgery. Re-examination of liver enzyme indicators and common bile duct structure showed no abnormalities in these 11 patients with abdominal pain again. Patients with FD were treated with gas

| Period | Case | 0 points, n | 1 point, n | 2 points, n | 3 points, n | 4 points, n | P value |

| Pre-EST | With FGID | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0.271 |

| Without FGID | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 8 | ||

| Post-EST | With FGID | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | < 0.001 |

| Without FGID | 66 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The Rome III guidelines divide the biliary-type SOD into three types and determine the patient’s treatment according to Milwaukee classification criteria and sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM) results[13-14]. The modified Milwaukee classification system recommends the use of a non-invasive method instead of ERCP to measure the diameter of the common bile duct and suggests that the biliary contrast agent emptying time should no longer be used as the basis for diagnosis, making it more suitable for clinical practice[15]. Cotton[16] found that the clinical remission rate of patients with type III with EST was only 23%. In addition, patients with type III showed a high degree of somatization disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive behavior and anxiety, which can cause dysfunction of the papillary sphincter[17]. Thus, endoscopy is not recommended for patients with type III, and the Rome IV guidelines remove biliary-type III SOD and categorize it as a functional digestive disease. There is evidence of organic biliary obstruction in patients with type I SOD, which is not a functional disease. Therefore, the Rome IV guidelines exclude previous patients with type I. Although the Rome IV guidelines only preserve the diagnosis of biliary-type II SOD, type I and type II include benign organic stenosis of the biliary sphincter, and all meet the diagnostic criteria for biliary abdominal pain, with abnormal liver enzymes and changes in the structure of the bile duct. Therefore, discussing EST has important value for the efficacy of treatment of the two types of biliary type SOD. This study included biliary-type SOD patients with type I and type II but did not include those with type III.

Biliary-type SOD is due to abnormal contraction of the biliary sphincter, resulting in obstruction of bile outflow through the bile duct and pancreatic duct junction, which leads to a series of clinical syndromes such as biliary abdominal pain[18]. EST can relieve the abnormal resistance of the sphincter of Oddi so that the clinical symptoms of patients are relieved, and the purpose of effective treatment is achieved[19], which is an important measure for biliary-type SOD[20]. A prospective study of EST in patients with biliary-type SOD found that symptoms disappeared in 96% of patients[5]. In this study, among 79 patients with biliary-type SOD, preoperative VRS-5 scores of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 points each accounted for 0 cases, 0 cases, 0 cases, 69 cases and 10 cases, respectively; postoperative VRS-5 scores of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 points each accounted for 67 cases, 6 cases, 2 cases, 4 cases and 0 cases, respectively. The VRS-5 score decreased significantly compared with the preoperative score (P < 0.05). Of 79 cases, 67 cases (84.8%) and 8 cases (10.1%) were obviously effective and effective, respec

For type I disease, Sugawa et al[21] treated 8 patients with EST; all patients had not undergone SOM and were followed up for an average of 26 mo. All their symptoms were relieved. In this study, 29 patients with type I disease were treated with EST, and 24 cases (82.8%) were obviously effective, 5 cases (17.2%) were effective, and the overall effective rate was 100.0% (29/29). The literature also shows that EST can relieve the pain symptoms of biliary-type SOD patients, with an effective rate of 87% to 100%[22]. Most scholars recommend that biliary-type SOD patients be directly treated with EST without SOM[18]. In this trial, EST has a significant effect on patients with type I, which is consistent with the previous reports.

For type II disease, it has been previously believed that patients should first undergo SOM to determine whether the base pressure of the papilla sphincter is elevated; then, whether to perform EST based on abnormal findings should be de

The test found that the treatment rate of EST for type IIa and type IIb patients was 100% (6/6) and 90.9% (38/44), which has good clinical effect for the two types. However, clinical practice is more inclined to carry out EST for type IIb patients. EST has a good effect for type IIa patients only with elevated liver enzymes, but a larger sample size is still needed for further verification.

FGID is a group of chronic, recurrent symptomatic functional diseases without organic changes in the gastrointestinal tract. The diagnosis of the disease mainly relies on similar clinical symptoms and no other pathological diseases that can be explained[25]. Traditional medical treatment of FGID is mainly to change bowel habits or improve visceral pain, such as with antispasmodic drugs, laxatives and others[26]. In addition, regulation of gastrointestinal microorganisms and gastrointestinal nerve regulation and some psychological treatment methods can be used to alleviate the clinical symptoms of patients[27]. The treatment of biliary-type SOD is different from that of FGID. Endoscopic treatment to relieve the obstruction of the papilla sphincter can effectively relieve the patients’ symptoms and improve biochemical indicators, but it has no obvious benefit on Rome III functional dyspepsia subdivision in postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome. There are few articles reporting the relationship and importance of biliary-type SOD and differential diagnosis of FGID[25].

In this study, 12 patients with recurrent abdominal pain after endoscopic treatment had a higher proportion of biliary-type SOD with FGID (11/12). There was no difference in VRS-5 scores between patients with biliary-type SOD (with FGID) and biliary-type SOD (without FGID) before EST (P > 0.05). Of the 12 biliary-type SOD (with FGID) patients, 11 patients had abdominal pain after EST; of 67 biliary-type SOD (without FGID) patients, 0 patients had abdominal pain after EST. Biliary-type SOD patients with FGID were more prone to experience abdominal pain after EST (P <0.05). FGID and biliary-type SOD have similar functional abdominal pain associations, affecting the clinician’s judgment of biliary-type SOD and affecting the performance of EST for SOD, which is an interfering factor for the curative effect of SOD. Clinical identification of FGID before EST is the key factor affecting the efficacy of EST for biliary-type SOD. After a clear diagnosis of this type of patient, only medication or endoscopic treatment has limited efficacy. It is recommended that appropriate medical treatment be given, while active endoscopic treatment is the key to improving the treatment of such patients. Similar to the conclusions of other studies, in biliary-type SOD patients with gastric emptying disorder, EST treatment was not effective (38%) in Freeman et al[28] study. Miyatani et al[4] retrospective study also showed that FD was a risk factor for recurrence of abdominal pain in patients with type I and type II disease.

Regarding the relationship between FGID and biliary-type SOD, there are few clinical related studies. This manuscript retrospectively assessed the effect of EST as a treatment for biliary-type SOD as well as the relationship between the comorbidity of FGID and treatment success. There are deficiencies in this study, but it is mainly a retrospective study. It is difficult to accurately diagnose SOD in patients with FGID, and more prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm.

In summary, this study suggests that EST is a minimally invasive, safe and effective treatment, and it has a definite curative effect on type I and type II biliary SOD. It is recommended to carefully identify the interfering factors of FGID for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary-type SOD. For patients with type I and II SOD combined with FGID, single EST or medical treatment has limited efficacy. It is recommended that EST and medicine be combined to improve the cure rate of such patients.

Although endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) has a positive therapeutic effect on biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), some patients still have little relief after EST, which implies that other functional abdominal pain may also be present with biliary-type SOD and interfere with the diagnosis and treatment of it.

This study explored the efficacy of EST in the treatment of biliary-type SOD and analyzed the reasons for the uncertainty of the efficacy of EST in the treatment of this kind of patients, that is, with FGID. The combined treatment of this kind of patient is the key to improve the efficacy of EST in the treatment of biliary-type SOD.

The objective was to investigate the therapeutic effect of EST in biliary-type SOD and analyze the reasons for the uncertainty of its curative effect to improve the curative effect of endoscopic therapy in this type patients.

This study compared and analyzed the clinical remission of different types of SOD patients after EST, including indicators such as postoperative pain, transaminase recovery and so on. The follow-up time was long, and the number of cases was sufficient.

This study suggested that EST is a minimally invasive, safe and effective treatment. For patients with type I and II SOD combined with FGID, single EST or medical treatment has limited efficacy. It is recommended that EST and medicine be combined to improve the cure rate of such patients. There are deficiencies in this study, but it is mainly a retrospective study. It is difficult to accurately diagnose SOD in patients with FGID, and more prospective randomized trials are needed to confirm.

EST is a minimally invasive, safe and effective treatment. For patients with type I and II SOD combined with FGID, single EST or medical treatment has limited efficacy. It is recommended that EST and medicine be combined to improve the cure rate of such patients.

There is a close relationship between FGID and biliary-type SOD, and more pro

We offer our profound thanks to the participants who contributed their time to this study. Thanks to Cai ZY, Li XZ and Liu H for collecting and editing the data. Thanks to Professor Ran X, Zeng WY and Yang NH for their editing guidance and modifications. Thanks to Professor Han M for revising the manuscript and providing final approval.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D, D, D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kawabata H, Kitamura K S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | Hu-Cheng Li, Jia-Hong Dong. The status of Oddi sphincter of function research. Zhonghua Gandan Waike Zazhi. 2006;12:140-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kutsumi H, Nobutani K, Kakuyama S, Shiomi H, Funatsu E, Masuda A, Sugimoto M, Yoshida M, Fujita T, Hayakumo T, Azuma T. Sphincter of Oddi disorder: what is the clinical issue? Clin J Gastroenterol. 2011;4:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tarnasky PR. Post-cholecystectomy syndrome and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: past, present and future. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:1359-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Miyatani H, Mashima H, Sekine M, Matsumoto S. Clinical course of biliary-type sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: endoscopic sphincterotomy and functional dyspepsia as affecting factors. Ther Adv Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;12:2631774519867184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Geenen JE, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, Toouli J, Venu RP. The efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy after cholecystectomy in patients with sphincter-of-Oddi dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:82-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Behar J, Biancani P. Effect of cholecystokinin and the octapeptide of cholecystokinin on the feline sphincter of Oddi and gallbladder. Mechanisms of action. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:1231-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterol. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1390] [Article Influence: 154.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Evans PR, Dowsett JF, Bak YT, Chan YK, Kellow JE. Abnormal sphincter of Oddi response to cholecystokinin in postcholecystectomy syndrome patients with irritable bowel syndrome. The irritable sphincter. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1149-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yarandi SS, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Mostajabi P, Malekzadeh R. Overlapping gastroesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: increased dysfunctional symptoms. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1232-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bennett E, Evans P, Dowsett J, Kellow J. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: psychosocial distress correlates with manometric dyskinesia but not stenosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:6080-6085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Behar J, Corazziari E, Guelrud M, Hogan W, Sherman S, Toouli J. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of oddi disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1498-1509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wan-Lu Gao, Xiao-Hai Wang. Preoperative selection of patient pain score and analysis of postoperative pain assessment. Shiyong Yixue Zazhi. 2013;29:110-112. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eversman D, Fogel EL, Rusche M, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Frequency of abnormal pancreatic and biliary sphincter manometry compared with clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:637-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Viceconte G, Micheletti A. Endoscopic manometry of the sphincter of Oddi: its usefulness for the diagnosis and treatment of benign papillary stenosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:797-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cotton PB, Elta GH, Carter CR, Pasricha PJ, Corazziari ES. Rome IV. Gallbladder and Sphincter of Oddi Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Cotton PB, Durkalski V, Romagnuolo J, Pauls Q, Fogel E, Tarnasky P, Aliperti G, Freeman M, Kozarek R, Jamidar P, Wilcox M, Serrano J, Brawman-Mintzer O, Elta G, Mauldin P, Thornhill A, Hawes R, Wood-Williams A, Orrell K, Drossman D, Robuck P. Effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction on pain-related disability following cholecystectomy: the EPISOD randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2101-2109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Corazziari E, Shaffer EA, Hogan WJ, Sherman S, Toouli J. Functional disorders of the biliary tract and pancreas. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II48-II54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sherman S, Ruffolo TA, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. Complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy. A prospective series with emphasis on the increased risk associated with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and nondilated bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1068-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ramesh J, Kim H, Reddy K, Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Impact of pancreatic stent caliber on post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram pancreatitis rates in patients with confirmed sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1563-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thatcher BS, Sivak MV Jr, Tedesco FJ, Vennes JA, Hutton SW, Achkar EA. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for suspected dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sugawa C, Park DH, Lucas CE, Higuchi D, Ukawa K. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for stenosis of the sphincter of Oddi. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1004-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Afghani E, Lo SK, Covington PS, Cash BD, Pandol SJ. Sphincter of Oddi Function and Risk Factors for Dysfunction. Front Nutr. 2017;4:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Morgan KA, Romagnuolo J, Adams DB. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty in the management of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreas divisum in the modern era. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:908-914; discussion 914-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Arguedas MR, Linder JD, Wilcox CM. Suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction type II: empirical biliary sphincterotomy or manometry-guided therapy? Endoscopy. 2004;36:174-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Piche T. Tight junctions and IBS--the link between epithelial permeability, low-grade inflammation, and symptom generation? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;26:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1140-1171.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, Boukouaci W, Dargel A, Oliveira J, Roger M, Tamouza R, Leboyer M, Boyer L. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264:651-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Freeman ML, Gill M, Overby C, Cen YY. Predictors of outcomes after biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy for sphincter of oddi dysfunction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:94-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |