Published online Nov 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9557

Peer-review started: June 6, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: July 13, 2021

Accepted: September 6, 2021

Article in press: September 6, 2021

Published online: November 6, 2021

Processing time: 145 Days and 2.2 Hours

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis (AAG) is a type of chronic gastritis that mainly affects the gastric corpus. Due to the lack of standard diagnostic criteria and overlaps with the courses of Helicobacter pylori-related atrophic gastritis, reports on the diagnostic strategy of AAG at an early stage are limited.

A 71-year-old woman with severe anemia was diagnosed with AAG. Endoscopic views and pathological findings showed the coexistence of normal mucosa in the gastric antrum and atrophic mucosa in the gastric fundus. Serological tests showed that anti-parietal cell antibodies and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies were both positive. Immunohistochemical results, which showed negative H+-K+ ATPase antibody staining and positive chromogranin A (CgA) staining, confirmed the mechanism of this disease. After vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation, the patient recovered well.

Successful diagnosis of AAG includes serological tests, endoscopic characteristics, and immunohistochemistry for H+-K+ ATPase and CgA antibodies.

Core Tip: The mechanism of autoimmune atrophic gastritis (AAG) involves H+-K+ ATPase. It is mostly identified during the late stage due to pernicious anemia. We present a case of AAG with anemia, typical endoscopic findings and immunohistochemical staining for H+-K+ ATPase and chromogranin A (CgA) antibodies. This case report demonstrates a successful diagnostic strategy for AAG that includes serological test (anti-parietal cell and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies), endoscopic characteristics and immunohistochemical results for H+-K+ ATPase and CgA antibodies.

- Citation: Sun WJ, Ma Q, Liang RZ, Ran YM, Zhang L, Xiao J, Peng YM, Zhan B. Validation of diagnostic strategies of autoimmune atrophic gastritis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(31): 9557-9563

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i31/9557.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i31.9557

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis (AAG), also known as type A gastritis, occurs more frequently in elderly women[1]. Its incidence is higher in Europe and America than in Asia[2], but its epidemiology remains unclear. AAG is an inflammatory disease that is limited to the mucosa of the gastric fundus and body, and its pathogenesis is not well understood. The molecular mechanism of H+-K+ ATPase is widely accepted. Anti-parietal cell antibodies (APCAs) and anti-intrinsic factor antibodies (AIFAs) are believed to act on H+-K+ ATPase located in the mucosa of the gastric fundus and body, which ultimately leads to the loss of oxyntic glands, decreased pepsinogen levels, and increased serum gastrin levels[2,3]. At an early stage, AAG has no typical symptoms. Some patients present only with iron-deficiency anemia and gastrointestinal symptoms. At a later stage, megaloblastic anemia, pernicious anemia, and subacute combined degeneration are often typical symptoms[4]. The diagnosis of AAG is challenging for gastroenterologists and pathologists. Most cases are diagnosed due to manifestations such as pernicious anemia.

Here, we present a case of pernicious anemia, which was diagnosed as AAG based on endoscopic features and immunohistochemical staining for H+-K+ ATPase antibody and chromogranin A (CgA), as well as a literature review of AAG. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

A 71-year-old woman presented to our hospital with progressive dizziness, headache, and weakness for > 1 year.

She also complained of blurry vision, tinnitus, acid reflux, belching, anorexia, and lower back pain. She did not have fever, and her skin and sclera were normal.

The patient had a history of gastric ulcer in the antrum, which was diagnosed 1 year prior to presentation. She received regular treatment for gastric ulcer and recovered well.

There was no personal history of tobacco or alcohol consumption or any other family medical history.

The patient’s height and weight were 155 cm and 42 kg, respectively. Physical examination revealed that the tongue was swollen and smooth. There were no positive signs in the chest or abdominal area.

Laboratory examination indicated a significantly decreased erythrocyte count (1.01 × 1012/L), hemoglobin level (45 g/L), leukocyte count (0.52 × 109/L), and platelet count (54 × 109/L). The mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration were 124.3 fL (normal range, 82.0–100.0 fL), 44.6 pg (normal range, 27.0–34.0 pg), and 359 g/L (normal range, 316.0–354.0 g/L), respectively. Routine urinalysis and liver and renal function tests were normal. The markers of myocardial injury were within normal limits. The serum levels of folic acid and vitamin B12 were 28.43 nmol/L (normal range, 7.0–54.10 nmol/L) and < 37 pmol/L (normal range, 133.0–675.00 pmol/L), respectively, while the serum ferritin level was normal. A bone marrow biopsy revealed a decrease in the number of red blood cells and an increase in their volume. Both APCAs and AIFAs were positive. The gastrin level was 266 pg/mL, which was higher than the normal level (13.0–115.0 pg/mL). The pepsinogen (PG) I and PG II levels were 12.8 (> 40.0) and 6.7 (< 27.0) ng/mL, respectively.

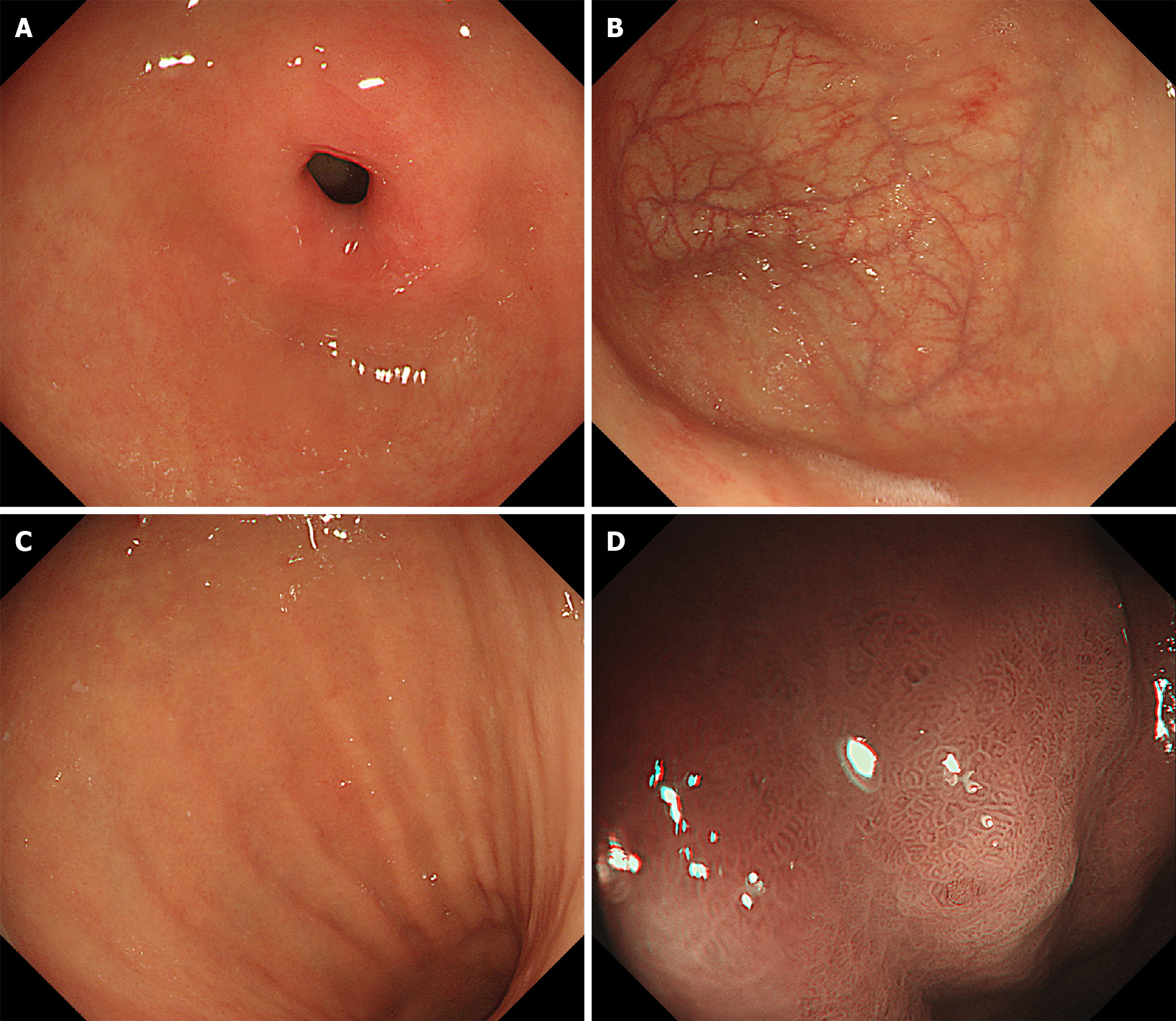

Endoscopic findings: Endoscopy revealed normal mucosa in the gastric antrum. However, the mucosa in the gastric fundus and body was atrophic. Narrow band imaging (NBI) showed atrophic changes without regular arrangement of collecting venules (RACVs) in the gastric fundus and body. Moreover, enlarged tubular structures and pseudopyloric changes were observed in the gastric fundus and body (Figure 1).

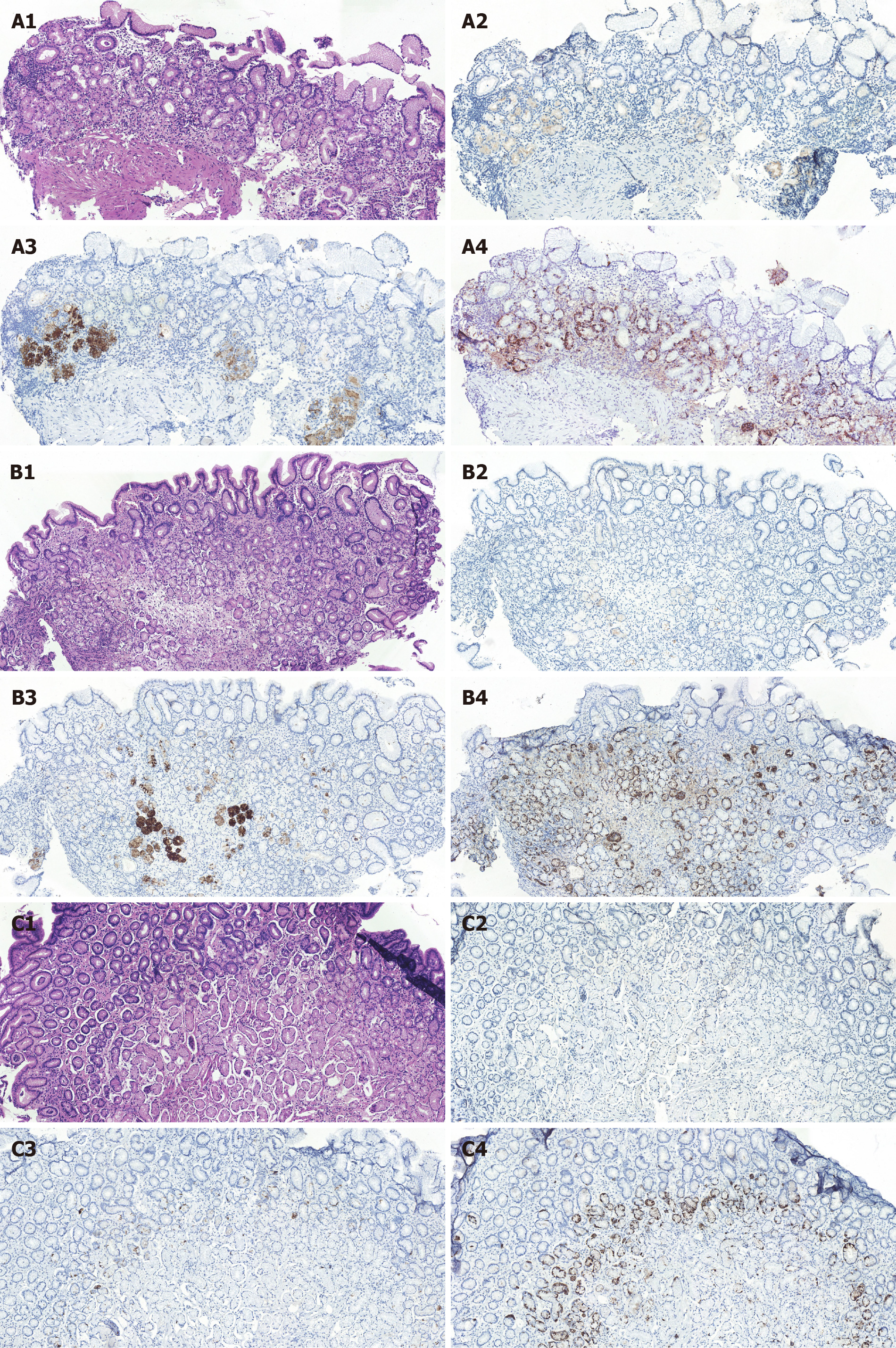

Pathological findings: Histology revealed decreased density of glands and lymphocyte infiltration in both the epithelium and lamina propria of the gastric fundus and body. However, the mucosa in the gastric antrum did not show atrophic changes. Immunohistochemical results showed negative H+-K+ ATPase antibody staining and positive CgA staining in most of the gastric mucosa. PG I staining was positive in a small number of glands in the gastric fundus and body (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis in this patient was pernicious anemia and AAG.

Blood transfusion was administered to correct severe anemia, and vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation were initiated to prevent pernicious anemia.

The patient recovered well and was discharged within 10 d. After receiving vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation for 8 mo, she recovered well without any other adverse or unanticipated events, and her hemoglobin level was 93 g/L.

Currently, the diagnosis of AAG is primarily based on endoscopic findings and histology of the gastric mucosa, as well as serological tests; however, there are no standards for the diagnosis of AAG[1,2]. Serological tests include target-specific antibodies (e.g., APCAs and AIFAs), serum PG I levels, PG I/II ratio, serum gastrin levels, and vitamin B12 levels. APCAs are present in 85%–90% of pernicious anemia cases[5], but their specificity for pernicious anemia is low[6]. In contrast, AIFAs have been shown to be more specific for pernicious anemia[7]. However, neither APCAs nor AIFAs can be used to identify the severity of atrophic gastritis.

PG I and PG II are two subtypes secreted by the chief cells and gastric glands, respectively. PG I and PG I/II ratio are recognized as specific markers for evaluating the function of gastric mucosa. Koc et al[8] reported that serum PG tests may provide valuable information for the diagnosis of atrophic gastritis and early-stage gastric cancer. However, they could not identify the cause of atrophic gastritis. Other serological biomarkers such as serum growth hormone and gastrin also have higher sensitivity in the diagnosis of atrophic gastritis[9,10], but they cannot identify the cause of atrophic gastritis. Ghrelin is produced by endocrine cells located in the gastric mucosa, and its sensitivity and specificity for atrophic gastritis in patients with parietal cell antibodies are 97.3% and 100%, respectively, which are higher than those of the PG I/II ratio and gastrin levels[11,12]. In this case, positive APCAs and AIFAs as well as high gastrin and low PG I levels indicated the diagnosis of AAG.

Endoscopically, AAG is characterized by the coexistence of normal mucosa in the gastric antrum and atrophic mucosa in the gastric fundus[2,4]. It is worth noting that endoscopic findings should not be used alone to diagnose AAG. In the early stage of AAG, there may be no obvious changes in the endoscopic views. As atrophy progresses, the mucosa of the gastric fundus and body may become thinner and flatter. The atrophic mucosa and enlarged tubular structures in the gastric fundus and body with the disappearance of RACVs can be detected by the NBI magnification[13]. It is well known that atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection also appears as an irregular arrangement of collecting venules. H. pylori-induced atrophic gastritis usually originates from the gastric antrum. Other endoscopic findings, such as mucosal swelling, diffuse redness, and sticky mucosa, can be considered characteristics of H. pylori infection[14,15]. These features may help distinguish between AAG and gastritis associated with H. pylori infection (Table 1). In our case, endoscopy revealed normal mucosa in the gastric antrum. In contrast, enlarged tubular structures combined with regular white zones and the disappearance of RACVs were found in the gastric fundus and body. However, sticky mucosa, redness, mucosal swelling, and enlarged folds were not observed in this case. These features suggested that this case could be diagnosed as AAG, which needs to be confirmed by histology.

| AAG | Helicobacter pylori-induced atrophic gastritis | |

| Serological tests | ||

| APCAs, AIFAs | Positive | Negative |

| PG I levels | Low | Normal |

| The PG I/PG II ratio | Low | Normal, or low |

| Gastrin levels, | Increased | Low, or normal |

| Vitamin B12 levels | Decreased | Often normal |

| Against H. pylori antibodies | Negative, but may be positive | Positive |

| Endoscopy | ||

| The distribution of atrophic mucosa | Corpus and fundus | Antrum, corpus and funds |

| Histology | ||

| Enterochromaffin-like cells | Common | Rare |

| Oxyntic glad involvement | Common | Rare |

| CgA staining | Positive | Negative |

| H+-K+ ATPase antibody Staining | Negative | Positive, but may be negative |

| Risk of gastric tumor | Gastric carcinoid | Gastric cancer |

Histology is considered a reliable method for diagnosing atrophic gastritis. However, it is difficult to distinguish between AAG and atrophic gastritis related to H. pylori infection. In addition, serological tests are not helpful in identifying AAG and atrophic gastritis related to H. pylori infection. Some studies have indicated that immunohistochemical staining is helpful in the diagnosis of AAG. Negative staining for H+-K+ ATPase antibody and positive staining for CgA are the main characteristics of AAG in immunohistochemical staining[16,17]. CgA is considered to be associated with hyperplasia of enterochromaffin-like cells and a high risk of gastric carcinoids[1]. Negative staining for H+-K+ ATPase antibody suggests that mucosal damage in the gastric fundus and body is caused by the destruction of parietal cells by H+-K+ ATPase antibodies[16,18]. In addition, lymphocyte infiltration leads to the destruction of parietal cells, loss of oxyntic glands, pseudopyloric glands, and proliferation of enterochromaffin-like cells in the mucosa of the gastric fundus and body[1,2]. However, these features are rarely found in atrophic gastritis related to H. pylori infection[15]. These characteristics of immunochemical staining can help distinguish AAG from H. pylori-associated atrophic gastritis (Table 1). These findings were consistent with those in the present study. In addition, we found that PG I staining was negative in most of the mucosa, which may indicate the destruction of chief cells.

However, to the best of our knowledge, data concerning the diagnostic accuracy of H+-K+ ATPase, CgA, and PG I antibodies in patients with AAG are limited. Finally, it is noteworthy that positive CgA antibody staining is common in patients with AAG[1,3]. Whether positive CgA antibody staining in our patient could be a predictive factor for gastric neuroendocrine tumors or gastric carcinoid remains unclear, as is its clinical relevance to survival and local relapse.

Serological tests (APCAs and AIFAs), endoscopic characteristics, and histological results, especially immunohistochemical staining for H+-K+ ATPase antibody and CgA, are important in the diagnosis of AAG. However, more clinical trials are needed to confirm these diagnostic criteria.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gravina AG, Shahini E S-Editor: Chang KL L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor:Guo X

| 1. | Minalyan A, Benhammou JN, Artashesyan A, Lewis MS, Pisegna JR. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:19-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Neumann WL, Coss E, Rugge M, Genta RM. Autoimmune atrophic gastritis--pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:529-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Massironi S, Zilli A, Elvevi A, Invernizzi P. The changing face of chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: an updated comprehensive perspective. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:215-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rodriguez-Castro KI, Franceschi M, Miraglia C, Russo M, Nouvenne A, Leandro G, Meschi T, De' Angelis GL, Di Mario F. Autoimmune diseases in autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rusak E, Chobot A, Krzywicka A, Wenzlau J. Anti-parietal cell antibodies - diagnostic significance. Adv Med Sci. 2016;61:175-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang Y, Weck MN, Schöttker B, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Gastric parietal cell antibodies, Helicobacter pylori infection, and chronic atrophic gastritis: evidence from a large population-based study in Germany. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:821-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harmandar FA, Dolu S, Çekin AH. Role of Pernicious Anemia in Patients Admitted to Internal Medicine with Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Oral Replacement Therapy as a Treatment Option. Clin Lab. 2020;66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ogutmen Koc D, Bektas S. Serum pepsinogen levels and OLGA/OLGIM staging in the assessment of atrophic gastritis types. Postgrad Med J. 2020;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Si JM, Cao Q, Gao M. Expression of growth hormone and its receptor in chronic atrophic gastritis and its clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2908-2910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Haruma K, Kamada T, Manabe N, Suehiro M, Kawamoto H, Shiotani A. Old and New Gut Hormone, Gastrin and Acid Suppressive Therapy. Digestion. 2018;97:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Checchi S, Montanaro A, Pasqui L, Ciuoli C, Cevenini G, Sestini F, Fioravanti C, Pacini F. Serum ghrelin as a marker of atrophic body gastritis in patients with parietal cell antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4346-4351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Panarese A, Romiti A, Iacovazzi PA, Leone CM, Pesole PL, Correale M, Vestito A, Bazzoli F, Zagari RM. Relationship between atrophic gastritis, serum ghrelin and body mass index. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;32:1335-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rodriguez-Castro KI, Franceschi M, Noto A, Miraglia C, Nouvenne A, Leandro G, Meschi T, De' Angelis GL, Di Mario F. Clinical manifestations of chronic atrophic gastritis. Acta Biomed. 2018;89:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li Y, Xia R, Zhang B, Li C. Chronic Atrophic Gastritis: A Review. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2018;37:241-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park B, Nam BH. Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1085-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 495] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Toh BH. Pathophysiology and laboratory diagnosis of pernicious anemia. Immunol Res. 2017;65:326-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nicolaou A, Thomas D, Alexandraki KI, Sougioultzis S, Tsolakis AV, Kaltsas G. Predictive value of gastrin levels for the diagnosis of gastric enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;99:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Oksanen AM, Lemmelä SM, Järvelä IE, Rautelin HI. Sequence analysis of the genes encoding for H+/K+-ATPase in autoimmune gastritis. Ann Med. 2006;38:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |