Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9269

Peer-review started: May 28, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 20, 2021

Accepted: August 30, 2021

Article in press: August 30, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 146 Days and 4.5 Hours

Neonatal hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is associated with a high risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and was previously believed to be associated with an increased risk of surgery.

A 3-day-old full-term male infant was admitted to the pediatrics department after presenting with “low blood glucose for 10 min”. Hypoglycemia was corrected by intravenous glucose administration and oral breast milk. On the 3rd d after admission, an ultrasound examination showed gas accumulation in the hepatic portal vein; this increased on the next day. Abdominal vertical radiograph showed intestinal pneumatosis. Routine blood examination showed that the total number of white blood cells was normal, but neutrophilia was related to age. There was a significant increase in C-reactive protein (CRP). The child was diagnosed with neonatal NEC (early-stage). With nil per os, rehydration, parenteral nutritional support, and anti-infection treatment with no sodium, his hepatic portal vein pneumatosis resolved. In addition, routine blood examination and CRP examination showed significant improvement and his symptoms resolved. The patient was given timely refeeding and gradually transitioned to full milk feeding and was subsequently discharged. Follow-up examination after discharge showed that the general condition of the patient was stable.

The presence of HPVG in neonates indicates early NEC. Early active anti-infective treatment is effective in treating NEC, minimizes the risk of severe NEC, and reduces the need for surgery. The findings of this study imply that early examination of the liver by ultrasound in a sick neonate can help with the early diagnosis of conditions such as NEC.

Core Tip: This manuscript reports a case of acute hepatic portal venous gas in a full-term infant and the results of a clinical analysis and literature review of the case. The findings of the study show that liver ultrasound examination is important for the early diagnosis of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). Effective and timely treatment of NEC reduces the risk of severe NEC and surgery.

- Citation: Yuan K, Chen QQ, Zhu YL, Luo F. Hepatic portal venous gas without definite clinical manifestations of necrotizing enterocolitis in a 3-day-old full-term neonate: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 9269-9275

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/9269.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9269

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) was first reported by Wolf and Evans in 1955 in patients with neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)[1,2]. HPVG is associated with various abdominal diseases, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions, some of which could require surgical intervention[3,4]. The diagnosis of HPVG is mainly through ultrasound, X-ray examination, or computed tomography. Advances in these detection methods have led to the detection of HPVG in several diseases with differing severities. HPVG is often a transient change during the disease progression. Its duration is often short, and there is no significant correlation with the prognosis of the disease. This case report presents a rare case of simple HPVG in a full-term infant without specific clinical manifestations. NEC was diagnosed through ultrasound examination and supportive blood tests, which allowed timely and effective intervention. After treatment, the patient's condition improved significantly, avoiding progression to severe NEC and the need for surgery.

A 3-day-old full-term male infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit within 10 min for monitoring and treatment because of the detection of blood glucose of 1.5 mmol/L after full breastfeeding 2 h after birth. A fecal occult blood test was weakly positive on the third day after birth with no specific clinical manifestations.

The patient was the second child of healthy Han parents. The patient was delivered through cesarean section at the 39th week of pregnancy, as the mother presented with a "thin scar uterine wall". The birth weight was 2720 g, and the Apgar score was 9-10-10/1-5-10 min. The patient was diagnosed with hypoglycemia because of the detection of blood glucose of 1.5 mmol/L after full breastfeeding 2 h after birth in the maternal neonatal unit. Glucose was administered after hospitalization, and the patient’s blood glucose levels were restored to normal levels with breastfeeding. A fecal occult blood test was positive on the third day after birth. The baby did not present with abdominal distension, diarrhea, fever, chills, vomiting, or other positive signs. Abdominal ultrasound examination was conducted, which showed “hepatic portal vein pneumatosis”.

There was no significant abnormality in the patient’s previous history.

The father and mother of the patient were in good health, and there was no reported history of genetic metabolic diseases in the family.

The patient showed a moderate reaction, and cardiopulmonary examination showed no abnormal features; the abdomen was soft and reacted when touched under the ribs of the liver and spleen. In addition, no blood or fluid was seeping from the umbilical stump. The patient showed fair limb movement and muscle tone, an original reflex leading out, and was slightly cool in extremities.

Analysis showed that the white blood cell (WBC) count was 10.70 × 109/L (15.0-20.0 × 109/L). The proportion of neutrophils was 64.2%, the proportion of lymphocytes was 22.8%, and the red blood cell (RBC) count was 5.09 × 1012/L (6.00-7.00 × 1012/L). The hemoglobin level was 202 g/L (170-200 g/L), platelet count was 261 × 109/L (100-350 × 109/L), and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 11.62 mg/L (0.0-8.0 mg/L). Stool examination showed the absence of WBCs, PLTs, and RBCs; however, the occult blood test was positive. TORCH screening was positive for rubella virus IgG antibody, cytomegalovirus IgG antibody, and HSV-1 virus antibody IgG, whereas the rest was negative. Liver and kidney function, electrolyte, and myocardial enzyme spectrum levels, and urine routine analysis revealed no significant abnormality.

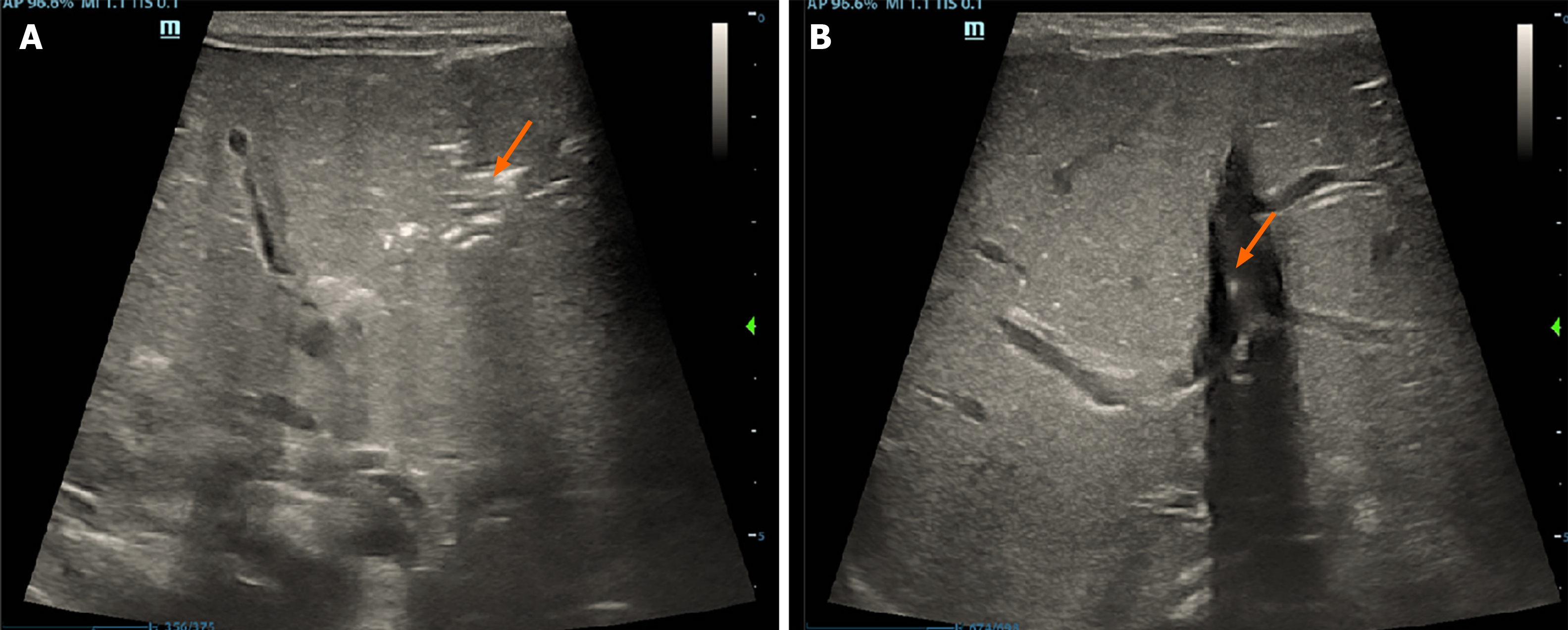

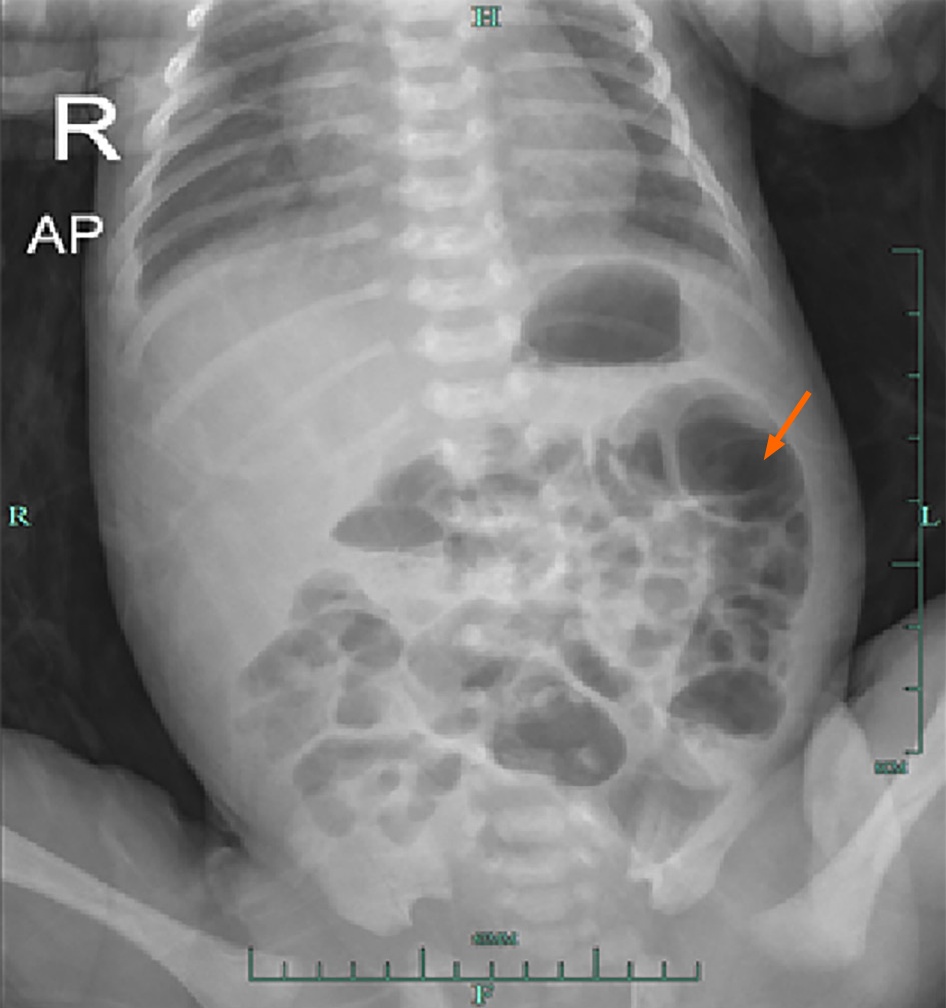

Abdominal ultrasound examination showed “hepatic portal vein pneumatosis” (Figure 1). Abdominal vertical X-ray showed the presence of intestinal pneumatosis, whereas no clear manifestation of intestinal wall pneumatosis was observed (Figure 2).

The diagnosis was NEC (early-stage) and neonatal hypoglycemia.

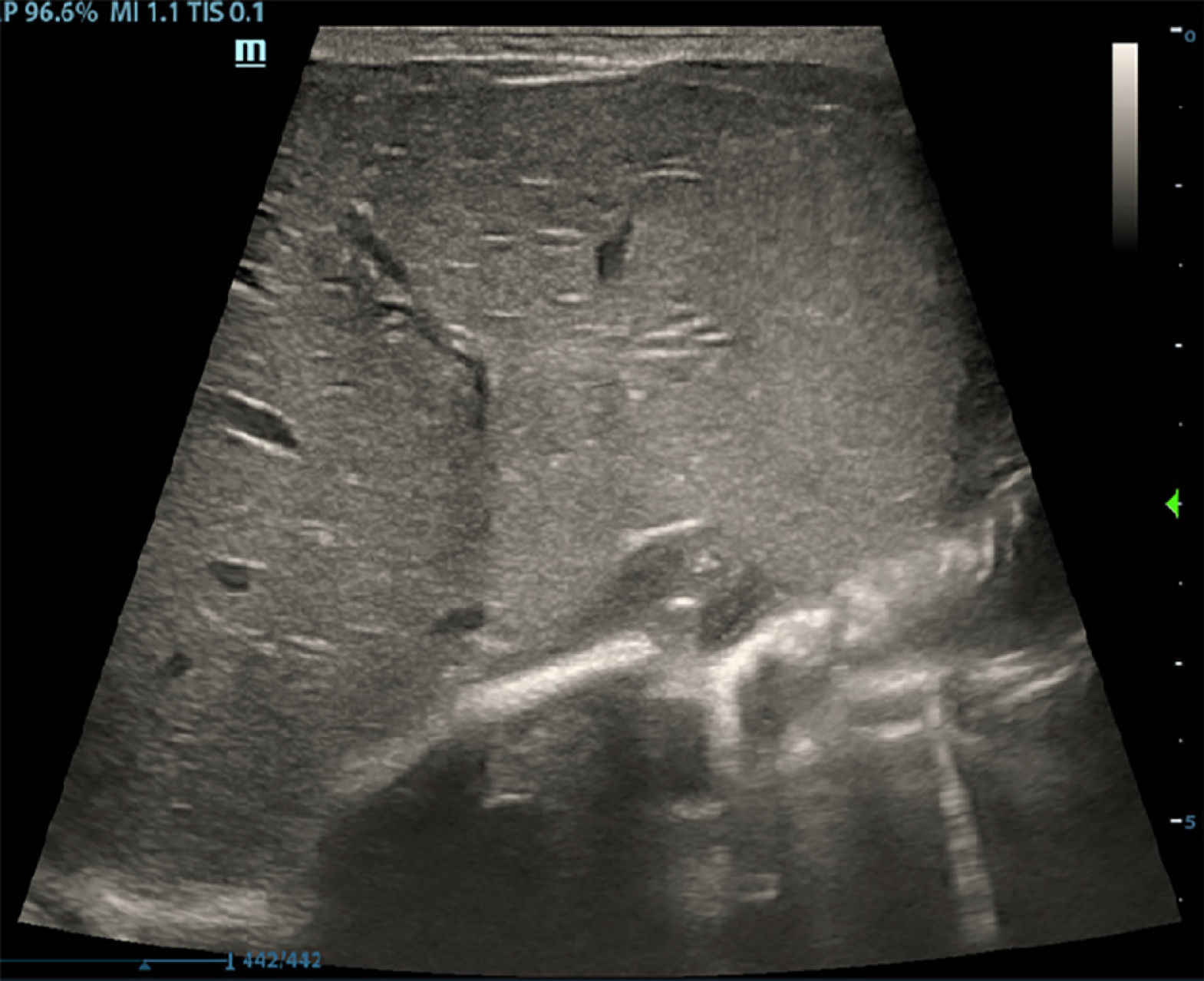

The patient underwent fasting, rehydration, and gastrointestinal decompression. The patient received anti-infective treatment with latamoxef sodium. After 3 d of treatment, routine blood and CRP examinations showed that the WBC count decreased to 10.19 × 109/L, the neutrophil count was 49.5%, the proportion of lymphocytes was 31.2%, the RBC count was 4.85 × 1012/L, the hemoglobin level was 182 g/L, the platelet count was 264 × 109/L, and the CRP level was 12.69 mg/L. Routine fecal analysis showed that occult blood was negative, and the thoracoabdominal film showed that the bowel inflation had improved (Figure 3). Thus, breastfeeding was resumed. After 7 d of treatment, the WBC count was 10.52 × 109/L, the neutrophil count was 44.5%, the lymphocyte count was 33.9%, the RBC count was 4.41 × 1012/L, the hemoglobin level was 168 g/L, the platelet count was 344 × 109/L and the CRP level was 3.87 mg/L (the specific laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Reexamination of ultrasound of the liver, gallbladder, spleen, and pancreas showed that the gas was effectively cleared from the hepatic portal vein (Figure 4).

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 10 | |

| WBCs (109/L) | 10.70 | 10.19 | 10.52 | 9.82 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 64.2 | 49.5 | 44.2 | 39.6 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 22.8 | 31.2 | 33.9 | 43.3 |

| RBCs (1012/L) | 5.09 | 4.85 | 4.41 | 4.31 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 202 | 182 | 168 | 160 |

| PLT (109/L) | 261 | 264 | 344 | 485 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.62 | 12.69 | 3.87 | < 0.5 |

| FOBT | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| HPVG | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

The patient was stable without complications and was discharged after 1 wk of treatment. Follow-up by telephone was carried out 1 wk and 1 mo after discharge. The baby’s condition remained stable with normal weight gain.

HPVG was first reported by Wolf and Evans in 1955 in association with NEC[1]. HPVG is mainly associated with several abdominal diseases, including benign conditions, conditions requiring surgical intervention, and life-threatening conditions[5]. Studies have not fully explored the specific mechanism of HPVG development. According to the clinical research analysis results currently retrieved, HPVG can be attributed to two factors: (1) Gas produced by the gas-producing microorganisms in the intestinal cavity or infection focus that enters the liver through blood circulation; or (2) gas-producing microorganisms present in the portal vein system producing gas that enters the circulatory system[6]. Previous studies reported that HPVG in childhood should be considered from the following aspects: HPVG is very common in NEC. NEC is a gastrointestinal disease seen mainly in the neonatal period. Neonates may develop severe sequelae such as short bowel syndrome, intestinal stenosis, or nervous system dysplasia. More than 90% of NEC cases occur in premature infants born before 37 wk of gestation. The other 10% of cases occur in full-term infants with insufficient mesenteric perfusion[7]. The incidence of NEC in the neonatal intensive care unit is 2%-5%, and the mortality is 20%-30%, whereas the incidence in very low birth weight infants is 4.5%-8.7%, and the mortality of very low birth weight infants is approximately 30%-50.9%[8-10]. Several abdominal infectious diseases, such as pyelonephritis, appendicitis, gangrene, cholecystitis or cholangitis, and abdominal tuberculosis, are associated with HPVG[11-14].In addition, intestinal ischemia caused by insufficient blood flow can cause HPVG. Intestinal ischemia is mainly caused by intestinal obstruction, vasculitis, and abdominal trauma[15]. Thromboembolism, tumors, and radiation are not common causes in infants[16].

Other conditions, such as neonatal umbilical vein catheterization, inflammatory bowel disease, lung disease (asthma and bronchopneumonia), milk protein allergy, food allergy, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, enteritis, and convulsions, may cause HPVG. These manifestations are often transient and have no specific clinical significance[17-20].

Abdominal ultrasound is highly sensitive and effective in the detection of HPVG; therefore, it can be used for early diagnosis, thus ensuring timely and effective intervention for NEC[5]. The main manifestations shown by ultrasound include hyperechoic granules flowing in the hepatic portal vein and hyperechoic plaques in the hepatic parenchyma. HPVG can also be detected by abdominal X-ray when the disease has progressed and the accumulation of gas is substantial. This phase is often transient. However, studies report that some patients may present with severe HPVG within 2 d[21].

In this case, only HPVG appeared without any typical clinical manifestations of NEC. Clinical experience suggested the possibility of NEC. Based on the improvement of blood and imaging-related examinations in response to treatment, the diagnosis of early NEC was confirmed. After active treatment, the patient's condition improved. The main difficulty in this case was whether anti-infective treatment was needed since only HPVG was observed, and also what course of anti-infective treatment to choose. Through this case, we can enrich the methods of early diagnosis of NEC, achieve early treatment, and avoid the occurrence of severe NEC.

A high degree of vigilance for early/timely detection of HPVG would allow timely diagnosis and treatment of the underlying conditions such as NEC in this case and thereby improve the outcome.

The authors would like to thank the patient’s family for agreeing to participate in this research.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abubakar MS, Strainiene S, Teragawa H S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Thompson AM, Bizzarro MJ. Necrotizing enterocolitis in newborns: pathogenesis, prevention and management. Drugs. 2008;68:1227-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Merritt CR, Goldsmith JP, Sharp MJ. Sonographic detection of portal venous gas in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:1059-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hussain A, Mahmood H, El-Hasani S. Portal vein gas in emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Salyers WJ Jr, Hanrahan JK. Hepatic portal venous gas. Intern Med J. 2007;37:730-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3585-3590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hunter CJ, Chokshi N, Ford HR. Evidence vs experience in the surgical management of necrotizing enterocolitis and focal intestinal perforation. J Perinatol. 2008;28 Suppl 1:S14-S17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jiang S, Yan W, Li S, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Shah PS, Shah V, Lee SK, Yang Y, Cao Y. Mortality and Morbidity in Infants <34 Weeks' Gestation in 25 NICUs in China: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eaton S, Rees CM, Hall NJ. Current Research on the Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Management of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Neonatology. 2017;111:423-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jones IH, Hall NJ. Contemporary Outcomes for Infants with Necrotizing Enterocolitis-A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2020;220:86-92.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rana AA, Sylla P, Woodland DC, Feingold DL. A case of portal venous gas after extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and obstructive pyelonephritis. Urology. 2008;71:546.e5-546.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kouzu K, Kajiwara Y, Aosasa S, Ishibashi Y, Yonemura K, Okamoto K, Shinto E, Tsujimoto H, Hase K, Ueno H. Hepatic portal venous gas related to appendicitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang M, Song J, Gong S, Yu Y, Hu W, Wang Y. Hepatic portal venous gas with pneumatosis intestinalis secondary to mesenteric ischemia in elderly patients: Two case reports. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dibra R, Picciariello A, Trigiante G, Labellarte G, Tota G, Papagni V, Martines G, Altomare DF. Pneumatosis Intestinalis and Hepatic Portal Venous Gas: Watch and Wait or Emergency Surgery? Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e923831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Angelelli G, Scardapane A, Memeo M, Stabile Ianora AA, Rotondo A. Acute bowel ischemia: CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:37-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Barczuk-Falęcka M, Bombiński P, Majkowska Z, Brzewski M, Warchoł S. Hepatic Portal Venous Gas in Children Younger Than 2 Years Old - Radiological and Clinical Characteristics in Diseases Other Than Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Pol J Radiol. 2017;82:275-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Allaparthi SB, Anand CP. Acute gastric dilatation: a transient cause of hepatic portal venous gas-case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:723160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saksena M, Harisinghani MG, Wittenberg J, Mueller PR. Case report. Hepatic portal venous gas: transient radiographic finding associated with colchicine toxicity. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:835-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Siddique Z, Thibodeau R, Jafroodifar A, Hanumaiah R. Pediatric milk protein allergy causing hepatic portal venous gas: Case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:246-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iguchi S, Alchi B, Safar F, Kasai A, Suzuki K, Kihara H, Hirota M, Nishi S, Gejyo F, Ohno Y. Hepatic portal venous gas associated with nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia in a hemodialysis patient. Clin Nephrol. 2005;63:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sharma R, Tepas JJ 3rd, Hudak ML, Wludyka PS, Mollitt DL, Garrison RD, Bradshaw JA, Sharma M. Portal venous gas and surgical outcome of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |