Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9159

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: April 28, 2021

Revised: May 19, 2021

Accepted: July 2, 2021

Article in press: July 2, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 203 Days and 0.8 Hours

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and life-threatening disease caused by inherited pathogenic mutations and acquired dysregulations of the immune system. Composite lymphoma is defined as two or more morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct lymphomas that occur in a single patient. Here, we report two cases of HLH secondary to composite lymphoma with mixed lineage features of T- and B-cell marker expression both in the bone marrow and lymph nodes in adult patients.

Two patients were diagnosed with HLH based on the occurrence of fever, pancytopenia, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hemophagocytosis and hyperferritinemia. Immunohistochemical staining of the axillary lymph node and bone marrow in case 1 showed typical features of combined B-cell and T-cell lymphoma. In addition, a lymph node gene study revealed rearrangement of the T-cell receptor chain and the immunoglobulin gene. Morphology and immunohistochemistry studies of a lymph node biopsy in case 2 showed typical features of T cell lymphoma, but immunophenotyping by flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow aspirate showed B cell lymphoma involvement. The patients were treated with high-dose methylprednisolone combined with etoposide to control aggressive HLH progression. The patients also received immunochemotherapy with the R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) regimen immediately after diagnosis. Both patients presented with highly aggressive lymphoma, and died of severe infection or uncontrolled HLH.

We present two rare cases with overwhelming hemophagocytosis along with composite T- and B-cell lymphoma, which posed a diagnostic dilemma. HLH caused by composite lymphoma was characterized by poor clinical outcomes.

Core Tip: Lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and life-threatening clinical disorder. In particular, composite lymphoma with mixed lineage features of T- and B-cell marker expression is extremely rare. We report two cases of HLH secondary to bi-lineage composite lymphoma with lymphocyte infiltrations both in the bone marrow and lymph nodes in adult patients. Case 1 showed typical features of combined B-cell and T-cell lymphoma in axillary lymph node and bone marrow biopsies. Case 2 showed typical features of T cell lymphoma in lymph node biopsy, and B cell lymphoma in bone marrow biopsy. Both patients highlight the diagnostic dilemma, therapeutic challenges and poor prognosis of HLH secondary to composite lymphoma.

- Citation: Shen J, Wang JS, Xie JL, Nong L, Chen JN, Wang Z. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to composite lymphoma: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 9159-9167

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/9159.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.9159

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and life-threatening clinical disorder characterized by uncontrolled hyper-activation of inflammatory responses due to inherited pathogenic mutations and acquired dysregulations of the immune system[1,2]. HLH can be classified into two subtypes: Primary and secondary. Secondary HLH can be triggered by underlying infection, autoimmune disease, or malignancy[3]. Malignancy-associated HLH is more common in adults in certain hematologic malignancies compared to children, and the actual incidence of this disease is unclear[1]. Lymphoma-associated HLH is comparatively common in T-cell or natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoma[4].

The term “composite lymphoma” (CL) was initially introduced as “the occurrence of more than one histological pattern of lymphoma in a single patient”[5]. According to the review by Kim, CL accounts for 1%-4.7% of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and can be associated with various combinations of T- and B-cell NHLs and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL)[5]. However, CL presenting with simultaneous occurrence of both B-cell and T-cell lymphomas is extremely rare[6]. Furthermore, only one case report of HLH secondary to CL of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) and small B-cell lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SLL/CLL) has been described[7]. It is worth mentioning that the presence of CL in this patient was confirmed at autopsy.

Here, we report two adult cases of HLH secondary to composite T- and B-cell lymphoma in both lymph nodes and bone marrow.

Case 1: A 50-year-old woman presented at our institution with lymphadenopathy in her bilateral armpits and groins and intermittent fever for 3 mo.

Case 2: A 65-year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to intermittent fever for 4 mo.

Case 1: Approximately 3 mo previously, this patient found an axillary lymph node mass and developed fever, she did not attend a hospital for diagnosis in April 2013. One month before, she was admitted to a local hospital due to fever, axillary and inguinal lymph node enlargement. Fever was not effectively improved with cephalosporin. She lost 10 kg in the previous 3 mo.

Case 2: Approximately 4 mo previously, this patient was admitted to a local hospital due to fever and respiratory infection in February 2013. He was treated with levofloxacin and carbapenem, and the infection was controlled. Three months before admission, the patient was treated at other hospital due to fever, abdominal pain and diarrhea. Positive cytomegalovirus (CMV)-DNA [3.60 × 106 copies/mL (2.50 × 102 copies/mL)] in peripheral blood confirmed CMV infection. After 1-wk of antiviral treatment with ganciclovir, the patient developed pancytopenia and reexamination of CMV-DNA was negative. One month prior to admission, he underwent fine needle aspiration biopsy of his cervical mass. Subsequent histopathological examinations revealed the suspicion of T cell lymphoma. Following his admission to our department in June 2013, the patient had intermittent fever, pancytopenia and splenomegaly. No significant weight loss was reported over the previous few months.

Case 1: The patient had the history of colon cancer and received six cycles of chemotherapy with tegafur and oxaliplatin 5 years ago.

Case 2: The patient’s history of past illness was remarkable for pruritus and increased eosinophilia for 5 years.

Both patients had no previous or family history of similar illnesses.

Case 1: After admission, the patient’s temperature was 39.0°C, heart rate was 120 bpm, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg. Physical examination revealed enlargement of multiple superficial lymph nodes and splenomegaly. Based on an abdominal ultrasound image, the long diameter of the spleen was 21.8 cm.

Case 2: The patient’s temperature was 36.0°C, heart rate was 72 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 110/75 mmHg. Physical examination revealed splenomegaly and superficial lymphadenopathy was not palpable.

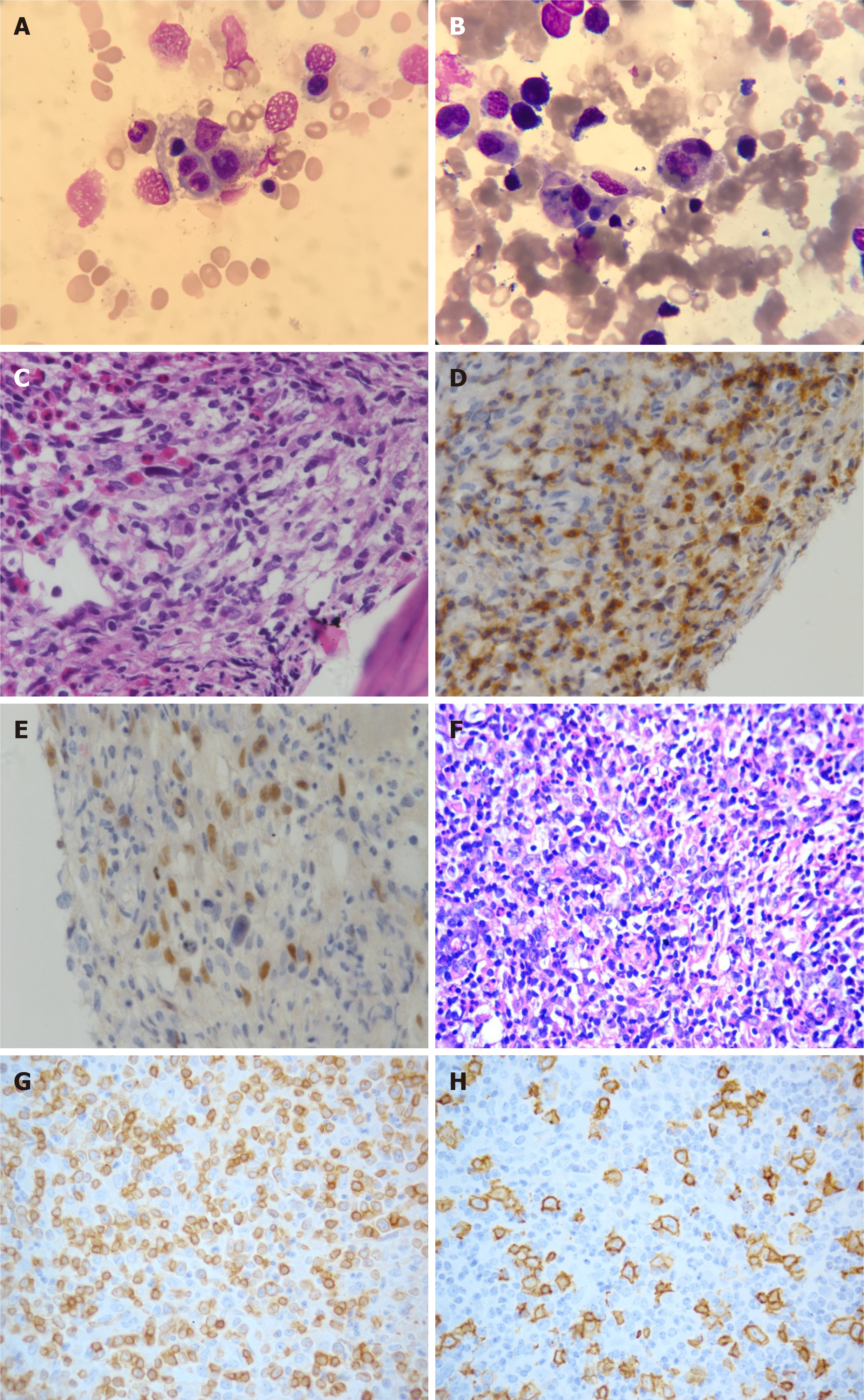

Case 1: Complete blood count revealed pancytopenia (white blood cells 1.4 × 109/L; hemoglobin 5.8 g/dL; and platelets 18 × 109/L), elevated levels of liver enzymes indicating possible liver injury, and an increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level [522 IU/L (120-250 IU/L)] indicating the tumor load. Prothrombin time (PT) was 17.7 s (11-15 s), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was normal and fibrinogen (FBG) level was 1.29 g/L (2-4 g/L). Increased ferritin level was 4760 ng/mL (11-306 ng/mL), and increased IL-2 receptor (SCD25) level was more than 44000 pg/mL (< 6500 pg/mL). A bone marrow biopsy revealed the occurrence of hemophagocytosis and lymphomatous infiltration (Figure 1A and B), along with atypical small or medium size neoplastic cell diffuse involvement with focal large irregular lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 1C). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of bone marrow samples exhibited positive staining for large neoplastic cell markers CD20, PAX5, CD30, and granzyme B, and small neoplastic cells expressing CD2, CD3, and CD7 markers, and non-immunoreactivity for CD56, CD10 and CD21 expression (Figure 1D and E). In situ hybridization for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) encoded nuclear RNA (EBER) in bone marrow biopsy was positive. The diagnosis was considered to be diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) involving bone marrow, EBV infection, and suspected T-cell lymphoma involvement. Cytogenetic study of the bone marrow showed a normal karyotype.

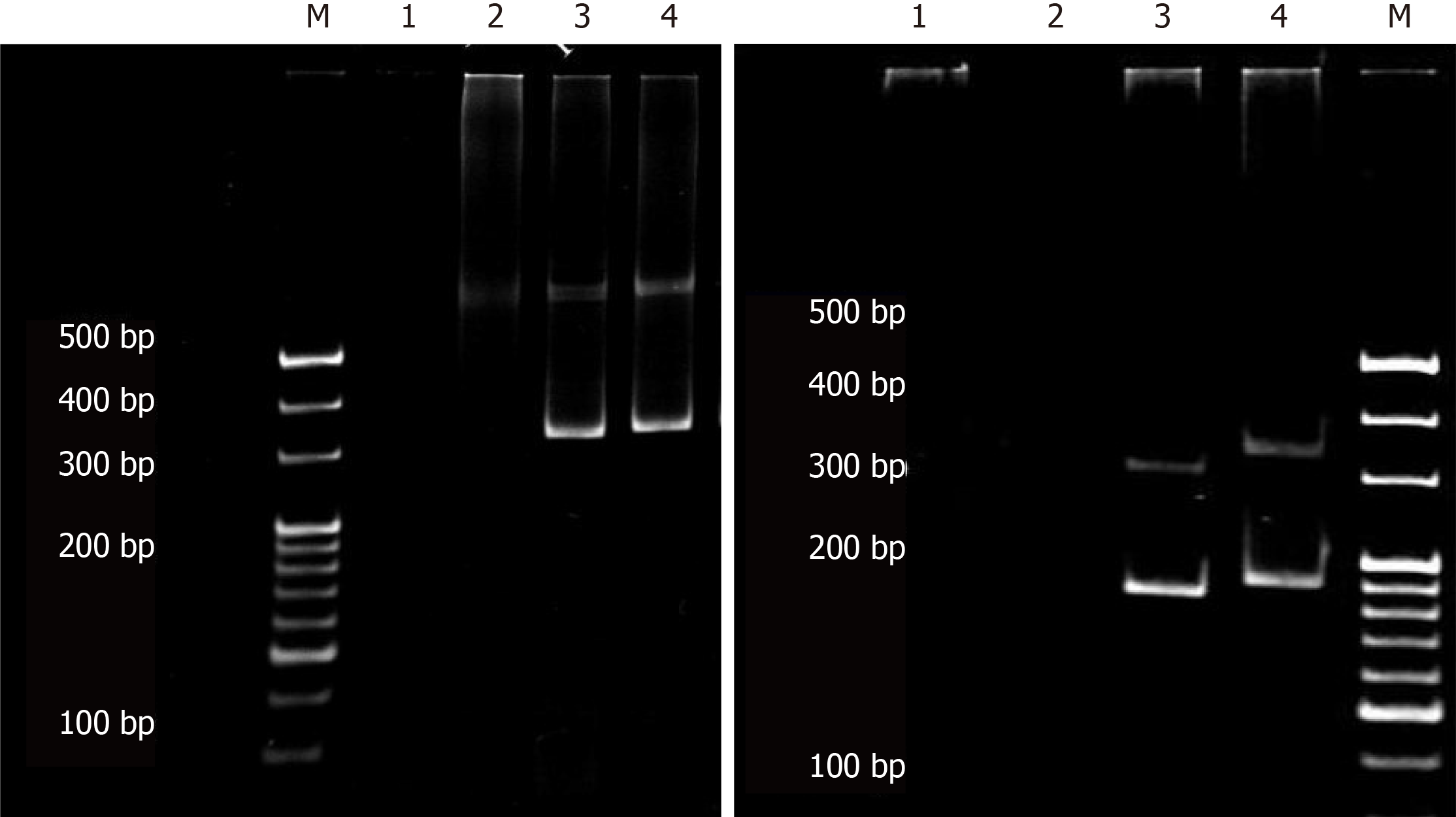

Histopathological examination of the left axillary lymph node biopsy sample revealed invasion of atypical lymphocytes, indicating the occurrence of lymphoma (Figure 1F). IHC staining of tumor cells showed positive expression of CD2, CD3, CD5, CD7, CD20, CXCL-13, and BCL6 markers, and negative results for CD10 and CD21 markers (Figure 1G and H). Furthermore, Ki-67 showed a proliferation index of over 50%. We then performed a T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement study of the lymph node, using a previously published protocol[8] to assess the clinical outcome and survival probability of the patient. Both clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene and TCR γ chain rearrangements were detected in the same specimen by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Figure 2).

Case 2: Laboratory investigations of his blood sample revealed pancytopenia (white blood cells 2.0 × 109/L; hemoglobin 9.6 g/dL; and platelets 37 × 109/L). Further investigations of liver functions showed an increased level of LDH [389 IU/L (120-250 IU/L)], decreased albumin level [23.9 g/L (40-55 g/L)], an increased ferritin level [980 ng/mL (11-306 ng/mL)], and decreased FBG level [1.49 g/L (2-4 g/L)], suggesting liver dysfunction. Further, investigation revealed a high level of soluble CD25 [> 44000 pg/mL (< 6500 pg/mL)], and reduced NK cell activity [13.85% (31%-41%)].

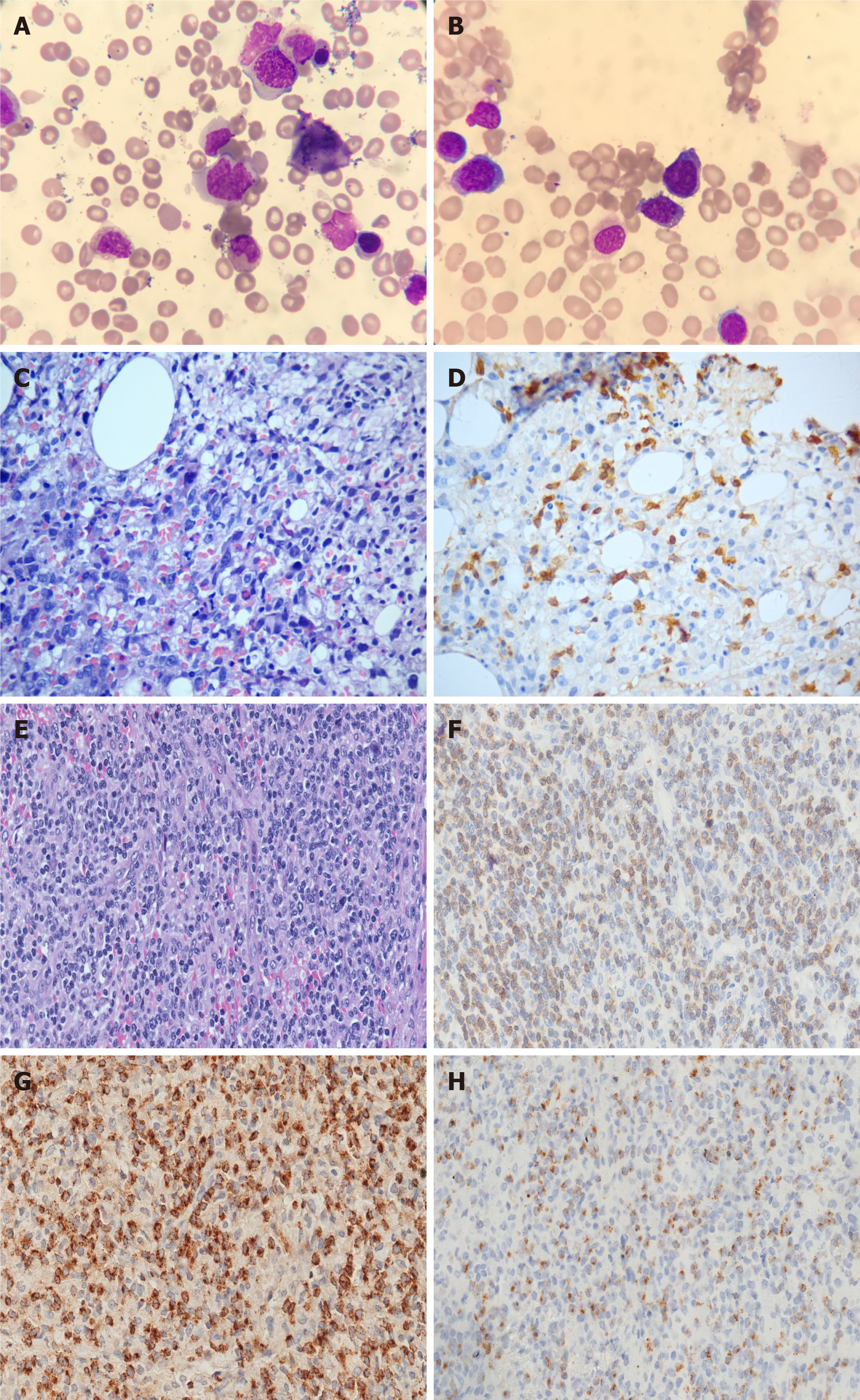

A bone marrow aspirate smear showed 2% of scattered hemophagocytosis (Figure 3A) and medium-sized atypical cells comprising 45% of the total cell population (Figure 3B). These atypical cells showed positive expression of CD19, CD20, CD79b and lambda light chain markers but were negative for CD5, CD23, CD10, CD103, and CD25 markers as measured by flow cytometry. Cytogenetic analysis of bone marrow revealed an abnormal karyotype of 47, XY, + 5 [22]. Furthermore, the bone marrow biopsy revealed diffuse infiltration of medium-sized atypical lymphocytes (Figure 3C) with positive staining for PAX5 (Figure 3D), BCL6, CD20, lambda light chain, and negative for EBER. Similarly, Ki-67 scoring was more than 50%, indicating high cell proliferation. Based on the above-mentioned bone marrow histopathological features, a diagnosis of DLBCL was made. However, the immunophenotype of the left inguinal lymph node biopsy was not consistent with the diagnosis of DLBCL. The atypical lymphocytes were positive for CD3 expression and negative for CD 20, CD79a, CD30, and CD56 markers. Granzyme B and TIA-1 (T-cell intracellular antigen) staining was positive, and in situ hybridization for EBER was negative (Figure 3E-H). Pathological diagnosis of the lymph node was PTCL-NOS.

Case 1: Enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed multiple cervical, axillary, mediastinal, retroperitoneal, pelvic and inguinal lymphadenopathy as well as splenomegaly. There were many low-density lesions in the spleen and spleen infarction.

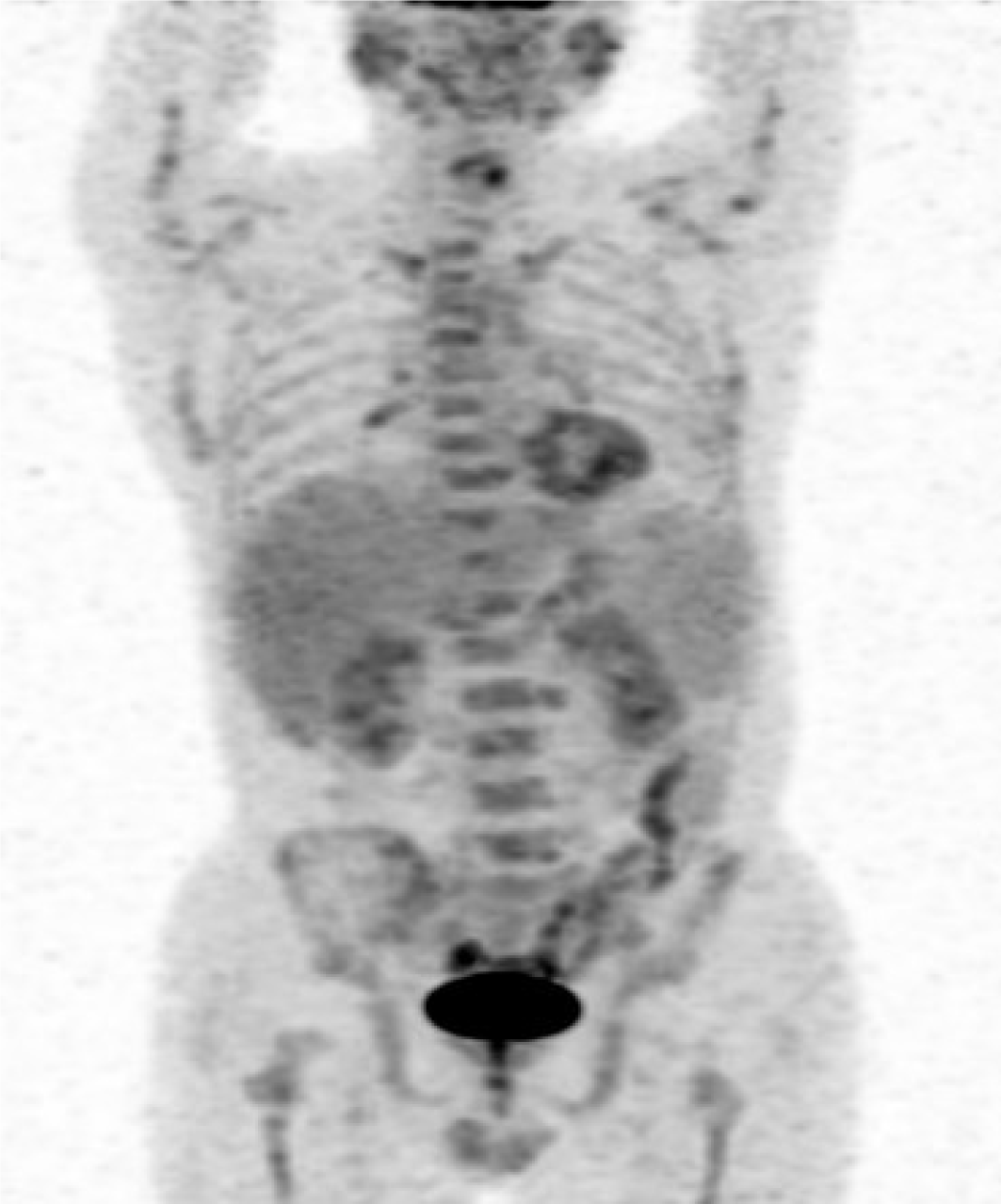

Case 2: Positron emission tomography-CT scanning revealed that the spleen was enlarged and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was normal. Hypermetabolic lesions were also detected in the bone marrow, bilateral inguinal and bilateral lung hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 4).

The patient was diagnosed with secondary HLH, PTCL-NOS with DLBCL stage IV with B symptoms.

The patient was diagnosed with HLH. HLH was secondary to stage IV composite PTCL-NOS and DLBCL lymphoma with B symptoms.

The patient was treated with a high dose of methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg) for 3 d and etoposide (100 mg/m2) one dose to control HLH. Three days later, the patient received combination chemotherapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone).

To control HLH, high dose methylprednisolone (5 mg/kg for 3 d, tapering over 2 wk), and etoposide (100 mg/m2) weekly for 2 wk were administered. The patient had recurrent fever and diarrhea, and he received a cycle of chemotherapy with R-CHOP.

After the first cycle of R-CHOP the patient presented with continued progression of lymphoma and eventually died of lymphoma 1 mo after diagnosis.

After the first cycle of R-CHOP the patient died due to severe pneumonia as he was diagnosed with HLH for 2 mo.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the diagnostic dilemma in detecting underlying lymphoma in patients, which could complicate therapeutic decisions. HLH with CL is characterized by poor clinical outcomes. In the present study, we report an uncommon and difficult-to-diagnosis clinical scenario of CL of PTCL-NOS combined with DLBCL. Both patients presented with HLH, which is an aggressive and potentially fatal immune disease. CLs with variable combinations have been reported, however, HLH with CL is rare with only one case reported so far[7,9-11].

Clinically, HLH is characterized by excessive immune activation and cytokine release (cytokine storm) stimulating bone marrow macrophages to engulf hemato

There are three possible reasons to explain the poor outcome of these two patients. First, both patients had intermittent fever for 3 mo before they were admitted to our hospital. It took time to clarify the diagnosis leading to exacerbation of HLH. Second, HLH in adults is life-threatening, and CL with bone marrow involvement may also be associated with a poor prognosis. Third, HLH in both patients highlighted the importance of immune dysregulation which was triggered by viral infection. EBER was positive in the case 1 and CMV-DNA was positive in case 2, which was associated with an immunosuppressive microenvironment.

In these patients, it was difficult for the hematopathologist to make the diagnosis when combinations of variable numbers of histocytes, B cells and T cells were present in the same tissue. The diagnosis of CL is quite challenging and is often neglected without comprehensive clonal tests. The incidence of CL has reportedly increased with the development of molecular genetics-based screening methods. The clinicopathological characteristics of CL have been well reviewed[5]. CLs include combinations of HL and NHL or two distinct types of NHL; however, composite B-cell and T-cell lymphoma have rarely been reported. The exact etiology and mechanisms of CL are unknown. There are several mechanisms to explain the simultaneous occurrence of the two different clones. The involvement of both genetic predisposition and environmental risk factors could be the major explanation for the development of CL in two unrelated precursors (B-cell and T-cell lymphoma). Bi-directional differentiation of pluripotent cells may be a possible reason for the two lineages. An EBV-driven PTCL with uncontrolled expansion of B-cell clones has been reported[15].

In conclusion, these two case reports presented unique findings in that rare HLH secondary to bi-lineage CL with lymphocyte infiltrations in both the bone marrow and lymph nodes were observed. EBV or CMV infection also reflected immune dysfunction. We hypothesize that the presence of immune dysregulation was associated with CL in these two cases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Palacios Huatuco RM S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Bhatt NS, Oshrine B, An Talano J. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Esteban YM, de Jong JLO, Tesher MS. An Overview of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46:e309-e313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Otrock ZK, Daver N, Kantarjian HM, Eby CS. Diagnostic Challenges of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17S:S105-S110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim YR, Kim DY. Current status of the diagnosis and treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood Res. 2021;56:S17-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Küppers R, Dührsen U, Hansmann ML. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of composite lymphomas. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e435-e446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim HK, Park CJ, Jang S, Cho YU, Park SH, Choi J, Park CS, Huh J, Chung YH, Lee JH. The first case report of composite bone marrow involvement by simultaneously developed peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alomari A, Hui P, Xu M. Composite peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified, and B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma presenting with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2013;21:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, Evans PA, Hummel M, Lavender FL, Delabesse E, Davi F, Schuuring E, García-Sanz R, van Krieken JH, Droese J, González D, Bastard C, White HE, Spaargaren M, González M, Parreira A, Smith JL, Morgan GJ, Kneba M, Macintyre EA. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17:2257-2317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2284] [Cited by in RCA: 2372] [Article Influence: 113.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang E, Papavassiliou P, Wang AR, Louissaint A Jr, Wang J, Hutchinson CB, Huang Q, Reddi D, Wei Q, Sebastian S, Rehder C, Brynes R, Siddiqi I. Composite lymphoid neoplasm of B-cell and T-cell origins: a pathologic study of 14 cases. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:768-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ibrahim F, Al Sabbagh A, Amer A, Soliman DS, Al Sabah H. Composite Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma and Mantle Cell Lymphoma; Small Cell Variant: A Real Diagnostic Challenge. Case Presentation and Review of Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e921131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aussedat G, Traverse-Glehen A, Stamatoullas A, Molina T, Safar V, Laurent C, Michot JM, Hirsch P, Nicolas-Virelizier E, Lamure S, Regny C, Picquenot JM, Ledoux-Pilon A, Tas P, Chassagne-Clément C, Manson G, Lemal R, Fontaine J, Le Cann M, Salles G, Ghesquières H, Copie-Bergman C, Sarkozy C. Composite and sequential lymphoma between classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal lymphoma/diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, a clinico-pathological series of 25 cases. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:244-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang Y, Wang Z. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2017;24:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bubik RJ, Barth DM, Hook C, Wolf RC, Muth JM, Mara K, Patnaik MS, Pruthi RK, Marshall AL, Litzow MR, Elliott MA, Hogan WJ, Shah MV, Begna KH, Alkhateeb H, Pardanani A, Ashrani AA, Call TG, Rivera CE, Camoriano JK, Go RS, Wolanskyj-Spinner AP, Parikh SA. Clinical outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis treated with the HLH-04 protocol: a retrospective analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61:1592-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lejeune M, Köse MC, Duray E, Einsele H, Beguin Y, Caers J. Bispecific, T-Cell-Recruiting Antibodies in B-Cell Malignancies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hoffmann JC, Chisholm KM, Cherry A, Chen J, Arber DA, Natkunam Y, Warnke RA, Ohgami RS. An analysis of MYC and EBV in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas associated with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified. Hum Pathol. 2016;48:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |