Published online Oct 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.8999

Peer-review started: April 12, 2021

First decision: May 11, 2021

Revised: May 19, 2021

Accepted: September 2, 2021

Article in press: September 2, 2021

Published online: October 26, 2021

Processing time: 191 Days and 18 Hours

Stroke has a great influence on the patient’s mental health, and reasonable psychological adjustment and disease perception can promote the recovery of mental health.

To explore the relationships among resilience, coping style, and uncertainty in illness of stroke patients.

A retrospective study was used to investigate 154 stroke patients who were diagnosed and treated at eight medical institutes in Henan province, China from October to December 2019. We used the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, and the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire to test the uncertainty in illness, resilience, and coping style, respectively.

Resilience had a significant moderating role in the correlation between coping style and unpredictability and information deficiency for uncertainty in illness (P < 0.05). Further, the tenacity and strength dimensions of resilience mediated the correlation between the confrontation coping style and complexity, respectively (P < 0.05). The strength dimension of resilience mediated the correlation between an avoidance coping style and the unpredictability of uncertainty in illness (P < 0.05), as well as correlated with resignation, complexity, and unpredictability (P < 0.05).

Resilience has moderating and mediating roles in the associations between coping style and uncertainty in illness, indicating that it is vital to improve resilience and consider positive coping styles for stroke patients in the prevention and control of uncertainty in illness.

Core Tip: This study aimed to examine the association between uncertainty in illness and coping styles, as moderated and mediated by resilience, in stroke patients. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first to explore this association. Further, in our sample of 154 stroke inpatients in China, we found evidence to support the significant mediating role that resilience plays in the correlation between uncertainty in illness and patients’ coping styles. We believe that these findings can have clinical and practical implications, and can be used to inform interventions to increase the resilience of stroke patients.

- Citation: Han ZT, Zhang HM, Wang YM, Zhu SS, Wang DY. Uncertainty in illness and coping styles: Moderating and mediating effects of resilience in stroke patients. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(30): 8999-9010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i30/8999.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i30.8999

Stroke is a cerebrovascular disease responsible for substantial morbidity, mortality, and disability worldwide. Various chronic non-communicable diseases are related to aging, such as dementia and stroke, which may lead to disability and long-term burdens like decline of capacity to take care of themselves[1]. Because stroke patients are affected by neurological dysfunction and brain damage, they bear more psychological pressure from being cared for in daily life and psychological burden caused by disease. Post-stroke depression has been increasing in recent years. The prevalence of post-stroke depression is 20% to 60% according to literature statistics, and 45.4% of them have mild depression within 1 mo after stroke[2]. Moderate depression accounted for 91.8%[3].

Coping style is considered to be a critical psychological resource for rebuilding patients’ affective disorder. It refers to the typical habitual tendency to solve problem and is considered as a strategy (or method) commonly used by people to cope with a wide range of stressors[4]. According to individuals' cognitive and behavioral tendencies, coping style can be divided into positive coping styles and negative coping styles. Positive coping refers to adopting positive psychology to deal with stress and to seek ways and methods to solve problems to reduce or eliminate the influence of negative emotions[5]. Negative coping refers to using fear, escape, and other emotions to deal with pressure, allowing things to develop further, and inability to find ways to solve the problem, which increases the malignant development of stressful events[6]. Some previous research has shown that coping styles can improve patients’ abilities to seek social support and overcome negative emotions, such as depression[7]. During stroke patients’ treatment and rehabilitation, an active coping style can help them confront their illness more proactively and promote long-term resilience. Moreover, positive coping styles could significantly assist stroke patients in regaining psychological well-being[8].

Uncertainty in illness has been proven to have a significant impact on the diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of stroke patients, due to the chronic nature of illness[9]. Uncertainty in illness is defined as the patient's feeling of uncertainty about disease-related symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis[10]. When the patient's disease experience cannot be matched with their personal experience in the process, due to the lack of information and so on, this causes the situation of uncertainty in illness[11]. Uncertainty in illness can form a cycle, which leads to the occurrence or recurrence of indeterminacy in a patient’s treatment, prognosis, and future. Besides, it also can affect their psychological adjustment, treatment compliance, and outlook on life[12]. Once the uncertainty of the disease occurs, it causes negative emotions that will not only interfere with the patient's search for information related to the disease, but also cause the deterioration of behavior and the interruption of treatment. Especially for stroke patients, patients with high disease uncertainty are often accompanied by increased anxiety, depression, and loss of feeling. These patients have relatively poor psychological adjustment ability, face more family problems, and have low quality of life[13].

Resilience is defined as an individual's ability to recover from stressful experiences. It is a dynamic form, with its expansion and contraction space, which can adjust to the changes of the environment and achieves dynamic regulation and adaptation to the environment. It is also a two-dimensional structure, which implies the exposure to adversity and the results of positive adjustment[14]. The first structure is adversity, which is usually the risk of a negative living environment on individuals, and the second structure is an active adaptation, which is the ability in social behaviour and the ability to meet the current developmental tasks[15]. Stroke recovery is a long-term process in which resilience has been shown to be a particularly important factor. Resilience is a way to help alleviate stress and emotional distress. It could affect stroke patients' responses to rehabilitation and long-term functional outcomes[16]. A longitudinal study regarding the resilience of stroke patients showed that the confrontation coping style was positively related to resilience[17]. Furthermore, resilience has been proven to have a protective effect by overcoming the negative effects of exposure to trauma[18].

Most studies have focused on the dual relationship between resilience and uncertainty in illness, resilience, and coping styles; however, research on the relationship between these three is limited. The objective of the present research was to analyze the moderating effect of resilience between coping style and disease uncertainty.

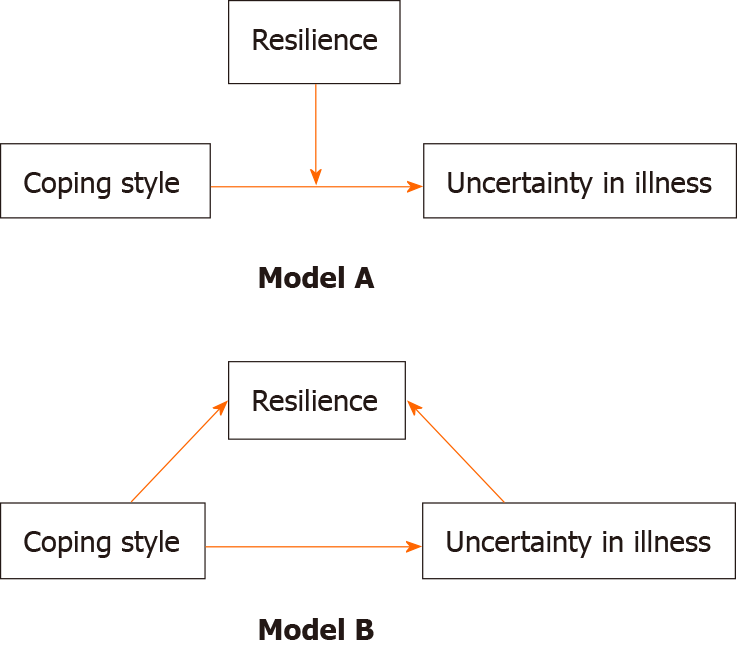

The model of mediation and moderation analysis is shown in Figure 1, the coping style of Models A and B includes three sub-models, according to different coping styles. Models A and B describe the moderating and mediating effects of resilience in the relationship between the three coping styles and uncertainty in illness, respectively (Figure 1).

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the associations among resilience, coping style, and uncertainty in illness of stroke patients. Based on the population intervention comparison outcome method, we recruited 154 people from different centres.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged 18-89 years; (2) patients who had experienced their first stroke; and (3) patients who met the Chinese Cerebrovascular Disease Clinical Management Guidelines as revised by Chinese Medical Association in 2019[19].

The exclusion criteria were as follows: Participants had no cognitive impairment and no obvious language dysfunction, and provided their informed consent to participate in this study. Participants who had a transient ischemic attack, multiple strokes, severe heart, liver, or renal disease, respiratory failure, malignant tumours, or suffering from cognitive decline (Mini-Mental State Examination score < 24), dementia, or other mental health disorders were excluded. Further, patients who were visually or hearing impaired, or unable to speak, were also excluded.

This study used a questionnaire package to collect data, including a self-designed social demographic questionnaire, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS), and the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire (MCMQ). The self-designed social demographic questionnaire included gender, age, marital status, education level, income, smoking history, drinking history, and medical history.

Resilience was assessed using the CD-RISC. The CD-RISC is a commonly used 25-item scale developed by Connor and Davidson, with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.90[20]. It has three dimensions: Tenacity, strength, and optimism. The scale uses a five-point scoring system, and each item is assigned a score according to its degree of conformity with one’s situation (0 = never to 4 = always). The total score of the scale is 100 points, and higher scores indicate stronger resilience. The CD-RISC scale was translated into Chinese by Wu et al[21], and the reliability and validity of the scale were tested. The Cronbach alpha value was 0.750[22]. From the pre-test of 30 samples, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for tenacity, strength, and optimism were 0.82, 0.79, and 0.75, respectively.

Uncertainty in illness was measured using the MUIS[23]. The scale has 33 items, including four dimensions: Ambiguity, complexity, information deficiency, and unpredictability. Higher scores indicate greater uncertainty in illness. Cronbach's alpha for the MUIS was 0.89.

Coping styles were assessed using the MCMQ[24]. The scale includes three dimensions: Confrontation, avoidance, and resignation. The higher the score in one of the three subscales, the higher a patient’s tendency to adopt this coping style[25]. During the pre-test of 30 samples, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for confrontation, avoidance, and resignation subscales in this study were 0.78, 0.72, and 0.71, respectively.

We trained the investigators and explained the aim of the study to the participants at each study site by home visit. Participants completed the questionnaire in writing. Prior to the survey, the patients signed an informed consent form. All data collected with informed consent was uploaded to the data management software for collation and analysis. During the process of data collection, we only recorded the code of the questionnaire, and the personal privacy information of participants was not recorded. The collected data was encrypted in the computer and destroyed after the research was completed.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) with the PROCESS plug-in for moderation and mediation analyses. Our study used Pearson’s correlations to analyze the associations among demographic variables, uncertainty in illness, coping styles, and resilience. Linear regression was used to analyze the mediating and moderating effects of resilience between uncertainty in illness and coping style. Uncertainty in illness as assed by the MUIS was the dependent variable, and demographic variables that could significantly impact uncertainty in illness were used as covariates. The three coping styles of the MCMQ were independent variables, and resilience was the mediating and moderating variable. We tested collinear effects among the variables before data analysis; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by sample mean and sampling error. If the 95%CI did not include zero, it indicated significant moderation and mediation of resilience.

Participants were diagnosed and treated in eight national stroke prevention and control centres in Henan province from October to December 2019. Table 1 shows that average participant age was 61.3 years old. Participants were mainly male (64.0%), over 60 years old (59.1%), married (91.6%), had a junior high school education (37%), and an income of 2001-3000 yuan per month (37.0%). The majority did not smoke (60.4%) or drink alcohol (67.0%).

| Variable | n (%) |

| Age group (yr) | |

| 18-45 | 8 (5.2) |

| 46-59 | 55 (35.7) |

| > 60 | 91 (59.1) |

| mean ± SD | 61.6 ± 11.25 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 54 (35.0) |

| Male | 100 (64.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 2 (1.3) |

| Married | 141 (91.6) |

| Other | 11 (7.1) |

| Education level | |

| Primary school or below | 41 (26.7) |

| Junior high school | 57 (37.0) |

| Senior high school | 33 (21.4) |

| University degree or above | 23 (14.9) |

| Monthly income | |

| < 2000 yuan per month | 39 (25.4) |

| 2001-3000 yuan per month | 57 (37.0) |

| 3001-5000 yuan per month | 49 (26.0) |

| 5001-8000 yuan per month | 12 (7.8) |

| > 8000 yuan per month | 6 (3.8) |

| Smoking status | |

| Yes | 61 (39.6) |

| No | 93 (60.4) |

| Drinking status | |

| Yes | 51 (33.0) |

| No | 103 (67.0) |

| Stroke classification | |

| Ischaemic | 124 (80.5) |

| Haemorrhage | 30 (19.5) |

| NIHSS score at admittance | |

| Mild stroke (0–4) | 118 (76.6) |

| Moderate stroke (5–15) | 30 (19.5) |

| Moderate to severe stroke (16–20) | 6 (3.9) |

| Severe stroke (> 20) | 0 (0) |

The vast majority of participants were diagnosed with ischemic stroke, and only 19.5% were diagnosed as having hemorrhagic stroke. According to National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score at admission, 76.6% of the participants had mild stroke, 19.5% had moderate stroke, and 3.9% had moderate to severe stroke.

The average score for resilience was 64.89, with scores ranging from 36 to 90, and the standard deviation of resilience score was 10.36. The average score for uncertainty in illness was 74.3, with scores ranging from 49 to 100, and the standard deviation of resilience score was 6.78. The average total score for coping style was 30 points, with scores ranging from 22 to 55, and the standard deviation of resilience score was 5.32.

Correlations among resilience, uncertainty in illness, and coping style are shown in Table 2. In this table, the first three items were from the MCMQ, the subsequent three items from the CD-RISC, and the final four items from the MUIS. Optimism was negatively correlated with complexity, information deficiency (P < 0.05), and unpredictability (P < 0.01) for uncertainty in illness. Tenacity was negatively correlated with ambiguity and complexity (P < 0.05). Strength was negatively correlated with resignation (P < 0.05), complexity (P < 0.01), and ambiguity (P < 0.05). The confrontation coping style was positively correlated with tenacity (P < 0.05). Avoidance was positively correlated with strength and negatively correlated with unpredictability (P < 0.05). Resignation was negatively correlated with strength (P < 0.01).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Confrontation | 1 | |||||||||

| Avoidance | 0.044 | 1 | ||||||||

| Resignation | 0.123 | 0.162a | 1 | |||||||

| Tenacity | 0.173a | 0.103 | -0.056 | 1 | ||||||

| Strength | 0.145 | 0.167a | -0.256b | 0.532b | 1 | |||||

| Optimism | -0.070 | 0.081 | -0.079 | 0.264b | 0.375b | 1 | ||||

| Ambiguity | -0.146 | 0.096 | -0.084 | -0.168 a | -0.150 | -0.052 | 1 | |||

| Complexity | -0.015 | 0.006 | 0.143 | -0.165 a | -0.211b | -0.171 a | -0.190 a | 1 | ||

| Information Deficiency | -0.156 | -0.115 | -0.115 | -0.024 | -0.145 | -0.051 | -0.195 a | -0.054 | 1 | |

| Unpredictability | -0.044 | -0.181 a | 0.041 | 0.060 | -0.201 a | -0.253b | -0.088 | 0.235b | 0.222b | 1 |

To analyse the effects of coping style and resilience on uncertainty in illness, four harmonic models were discussed from Model A of uncertainty in illness classification. The three dimensions of uncertainty in illness were taken as dependent variables, coping styles as independent variables, and resilience as the moderator. As presented in Table 3, resilience played a significant moderating role in the correlation between coping style, unpredictability, and information deficiency (P < 0.05).

| Variable | SE | t | B (95%CI) | R² | F | P value |

| Model 1A (unpredictability) | ||||||

| Coping style | 0.040 | 2.604 | 0.107 | |||

| Confrontation | 0.067 | 0.544 | 0.044 | |||

| Voidance | 0.089 | -2.386 | -0.193 | |||

| Resignation | 0.132 | 0.412 | 0.823 | |||

| Coping style × resilience | 0.106 | 6.058 | 0.001a | |||

| Confrontation | 0.066 | 0.310 | 0.025 | |||

| Voidance | 0.087 | -1.914 | -0.152 | |||

| Resignation | 0.133 | 0.007 | 0.001 | |||

| Optimism | 0.123 | -2.625 | -0.219 | |||

| Tenacity | 0.041 | 2.758 | 0.252 | |||

| Strength | 0.074 | -2.306 | -0.231 | |||

| Model 2A (indeterminacy) | ||||||

| Coping style | 0.040 | 2.057 | 0.108 | |||

| Confrontation | 0.090 | -1.997 | -0.161 | |||

| Voidance | 0.120 | 1.089 | 0.088 | |||

| Resignation | 0.177 | 1.095 | 0.089 | |||

| Coping style × resilience | 0.065 | 1.337 | 0.265 | |||

| Confrontation | 0.092 | -.1546 | -0.129 | |||

| Voidance | 0.122 | 1.412 | 0.117 | |||

| Resignation | 0.187 | 0.642 | 0.055 | |||

| Optimism | 0.173 | -0.096 | -0.008 | |||

| Tenacity | 0.058 | -1.186 | -0.113 | |||

| Strength | 0.104 | -0.699 | -0.073 | |||

| Model 3A (information deficiency) | ||||||

| Coping style | 0.044 | 2.307 | 0.079 | |||

| Confrontation | 0.065 | -1.750 | -0.141 | |||

| Voidance | 0.089 | -1.165 | -0.094 | |||

| Resignation | 0.129 | -1.117 | -0.091 | |||

| Coping style × resilience | 0.097 | 2.898 | 0.037a | |||

| Confrontation | 0.066 | -1.862 | -0.152 | |||

| Voidance | 0.087 | -1.015 | -0.083 | |||

| Resignation | 0.134 | -1.046 | -0.088 | |||

| Optimism | 0.124 | -2.506 | -0.215 | |||

| Tenacity | 0.041 | -1.217 | -0.114 | |||

| Strength | 0.074 | 1.013 | 0.104 | |||

| Model 4A (complexity) | ||||||

| Coping style | 0.022 | 1.116 | 0.344 | |||

| Confrontation | -0.033 | -0.408 | -0.033 | |||

| Voidance | -0.017 | -0.207 | -0.017 | |||

| Resignation | 0.150 | 1.818 | -1.117 | |||

| Coping style × resilience | 0.068 | 2.413 | 0.069 | |||

| Confrontation | -0.007 | -0.089 | -0.007 | |||

| Voidance | 0.024 | 0.296 | 0.024 | |||

| Resignation | 0.099 | 1.156 | 0.099 | |||

| Optimism | -0.105 | -1.199 | -0.105 | |||

| Tenacity | -0.074 | -0.774 | -0.074 | |||

| Strength | -0.110 | -1.056 | -0.110 |

As shown in Table 4, the dimensions of tenacity and strength partially mediated the correlation between confrontation and complexity, respectively (P < 0.05). The strength dimension partially mediated the correlation between avoidance and unpredictability (P < 0.05), as well as the correlation between resignation, complexity, and unpredictability (P < 0.05).

| Variable | SE | t | B (95%CI) | P value |

| Model 1B (complexity) | ||||

| Confrontation | 0.046 | -0.191 | -0.015 | |

| Confrontation × tenacity | 0.042a | |||

| Confrontation | 0.047 | 0.164 | 0.013 | |

| Tenacity | 0.025 | -2.048 | -0.167 | |

| Model 2B (complexity) | ||||

| Confrontation | 0.046 | -0.191 | -0.015 | |

| Confrontation × strength | 0.009a | |||

| Confrontation | 0.046 | 0.192 | 0.015 | |

| Strength | 0.041 | -2.656 | -0.213 | |

| Model 3B (unpredictability) | ||||

| Avoidance | 0.088 | -2.265 | -0.181 | |

| Avoidance × strength | 0.030a | |||

| Avoidance | 0.088 | -1.895 | -0.151 | |

| Strength | 0.059 | -2.192 | -0.175 | |

| Model 4B (complexity) | ||||

| Resignation | 0.090 | 1.781 | 0.143 | |

| Resignation × strength | 0.024a | |||

| Resignation | 0.092 | 1.161 | 0.095 | |

| Strength | 0.042 | -2.281 | -0.187 | |

| Model 5B (unpredictability) | ||||

| Resignation | 0.131 | 0.509 | 0.041 | |

| Resignation × strength | 0.015a | |||

| Resignation | 0.092 | -0.131 | -0.011 | |

| Strength | 0.042 | -2.465 | -0.203 |

In China, only a few studies have been published yet on the relationships among coping style, resilience, and uncertainty in illness after stroke. Findings of the current study supported the hypothesis that coping style may affect the development of uncertainty in illness. Additionally, resilience was shown to moderate the correlation between coping style and complexity and information deficiency. This study found that coping style affects uncertainty in illness. This supports previous research which considered coping style as a factor that affects uncertainty in illness[25]. Based on the theory of resilience and related concepts in the field of psychology, this study investigated the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness for stroke patients, and whether resilience plays a mediating and moderating role. In our proposed model, resilience partially mediated the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness.

This study found that coping styles affect uncertainty in illness. Coping style, as a natural response when people face stress events, has been proven to be one of the important factors that affect the uncertainty in illness[26]. Zyga et al[27] believe that avoidance is not escape, but a way to divert attention or temporarily alleviate contradictions, and to some extent, it can reduce the occurrence of negative psychology. This provides some support for the result that avoidance coping style and unpredictability were negatively correlated in this study. In clinical nursing, patients can be instructed to take evasive coping style, so as to alleviate the uncertainty in illness caused by patients in the process of disease treatment, and thus promote rehabilitation.

The research results also confirmed that the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness is moderated by resilience. Specifically, resilience can reduce the negative impact of negative coping styles on uncertainty in illness and can enhance the positive impact of positive coping styles on uncertainty in illness. Resilience is characterized by a high degree of positive mentality[28]. Therefore, a flexible individual may have a broader mentality, which helps to improve emotional stability and weaken the negative impact of uncertainty in illness. A previous study showed that a positive coping style and better resilience can make patients adapt better to stress events, thus improving his or her quality of life. Although stroke patients have limited knowledge and information about the disease, they recognize and accept it and do not question the disease itself[29]. Besides, stroke as a chronic disease does not have a strong complexity, which has slight psychological impact on the patient, so the indeterminacy and complexity of uncertainty in illness are not significant in this study[30].

In the current study, resilience plays a mediating and moderating role in the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness. Namely, coping style can indirectly affect uncertainty in illness by influencing resilience. Resilient individuals are able to successfully adapt to adversity and maintain mental health. Resilience is a dynamic process in which individuals mobilize resources to recover from adversity. This process can be influenced both internally and externally[15]. Coping style, as an important external factor, also plays an important role in the construction of resilience. Positive coping style is helpful for the long-term construction of resilience. When coping style is determined, the reduction of resilience as an intermediary variable will directly affect the uncertainty in illness of stroke patients, thus reducing the patients' future quality of life and social support resources[31].

Resilience mediates as well as moderates the relationship between coping styles and uncertainty in illness, which has clinical significance. Resilience can be cultivated, for example, some studies have found that resilience was affected by personal characteristics[32]. Moreover, Kirby et al[33] demonstrated that resilience plays an important controlling role in inhibiting negative stressors. This study provides a theoretical basis for clinical nursing staff to guide patients to use avoidance and resignation coping styles as little as possible, encourage confrontation coping style, and encourage patients to participate in various treatment decisions, learn more about stroke-related knowledge, discuss experiences with patients with the same disease, change their resigned attitude, and enable them to actively face changes in their own conditions, thus reducing the uncertainty in illness. It provides some advice for medical staff to help patients build and improve their resilience.

Some studies show that the degree of uncertainty in illness has a significant correlation with the patient's function and symptoms. When the degree of uncertainty in illness decreases, the patient's function and cognition level will increase[34]. In addition, the uncertainty in illness is also significantly related to the support of health workers. When the uncertainty in illness is reduced, patients will have higher compliance with the treatment of health workers. Moreover, the reduction of uncertainty in illness can also reduce the psychological burden of patients, so that they can reduce the psychological pressure of disease treatment and care[35]. Therefore, it has certain influence on the clinical intervention effect and intervention mode of the medical personnel for patients.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size in our study was small, so the interpretation of the results is limited. Second, the process of data collection came from the patient’s self-report, therefore, recall bias is inevitable, as some participants may not be able to recall details for some responses. Third, due to differences in the regions, religion, and time of onset of patients collected in the sample, we may have errors in the recruitment process of the participants. Fourth, the age of the subjects included in this study is quite different, which may limit the interpretation of the results as a confounding factor. It is hoped that future studies can consider the influence of age on related variables.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the relationship among coping style, resilience, and uncertainty in illness. The findings indicated that resilience could moderate and mediate the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness. Therefore, the medical policies should formulate and improve relevant guidelines for coping ability and psychological adaptation in stroke patients. It is recommended that medical institutions should strengthen the psychological intervention and counseling for stroke patients to enhance their adaptability and coping ability during illness. Individuals with stroke need to improve their understanding of the disease by reading stroke prevention and treatment guidelines and participating in health education seminars to improve their resilience during their illness.

Stroke has a great impact on the mental health of patients. Positive coping style, good resilience, and less disease uncertainty can promote the recovery of mental health of stroke patients.

There is no consensus on the relationship among disease uncertainty, resilience, and coping style of stroke patients.

This study aimed to analyze the moderating and mediating of resilience between coping style and disease uncertainty.

The Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale, the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, and the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire were used to test the uncertainty in illness, resilience, and coping style, respectively.

Resilience had a significant moderating role in the correlation between coping style and unpredictability and information deficiency for uncertainty in illness. Further, the tenacity and strength dimensions of resilience mediated the correlation between the confrontation coping style and complexity, respectively. The strength dimension of resilience mediated the correlation between an avoidance coping style and the unpredictability of uncertainty in illness, as well as correlated with resignation, complexity, and unpredictability.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined the relationship among coping style, resilience, and uncertainty in illness. The findings indicated that resilience could moderate and mediate the relationship between coping style and uncertainty in illness.

It is recommended that medical institutions should strengthen psychological intervention and counseling for stroke patients to enhance their adaptability and coping ability during illness.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Physiology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lu Q, Zhang L S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Liu L, Chen W, Zhou H, Duan W, Li S, Huo X, Xu W, Huang L, Zheng H, Liu J, Liu H, Wei Y, Xu J, Wang Y; Chinese Stroke Association Stroke Council Guideline Writing Committee. Chinese Stroke Association guidelines for clinical management of cerebrovascular disorders: executive summary and 2019 update of clinical management of ischaemic cerebrovascular diseases. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5:159-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Das J, G K R. Post stroke depression: The sequelae of cerebral stroke. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:104-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:221-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 582] [Cited by in RCA: 685] [Article Influence: 76.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Wei C, Gao J, Chen L, Zhang F, Ma X, Zhang N, Zhang W, Xue R, Luo L, Hao J. Factors associated with post-stroke depression and emotional incontinence: lesion location and coping styles. Int J Neurosci. 2016;126:623-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Ding Y, Yang Y, Yang X, Zhang T, Qiu X, He X, Wang W, Wang L, Sui H. The Mediating Role of Coping Style in the Relationship between Psychological Capital and Burnout among Chinese Nurses. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0122128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sastrawan S, Newton JM, Malik G. Nurses' integrity and coping strategies: An integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:733-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Al-Yateem N, Docherty C, Altawil H, Al-Tamimi M, Ahmad A. The quality of information received by parents of children with chronic ill health attending hospitals as indicated by measures of illness uncertainty. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31:839-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lew B, Huen J, Yu P, Yuan L, Wang DF, Ping F, Abu Talib M, Lester D, Jia CX. Associations between depression, anxiety, stress, hopelessness, subjective well-being, coping styles and suicide in Chinese university students. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0217372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoth KF, Wamboldt FS, Ford DW, Sandhaus RA, Strange C, Bekelman DB, Holm KE. The social environment and illness uncertainty in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22:223-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arias-Rojas M, Carreño-Moreno S, Posada-López C. Uncertainty in illness in family caregivers of palliative care patients and associated factors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2019;27:e3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Varner S, Lloyd G, Ranby KW, Callan S, Robertson C, Lipkus IM. Illness uncertainty, partner support, and quality of life: A dyadic longitudinal investigation of couples facing prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28:2188-2194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ni C, Peng J, Wei Y, Hua Y, Ren X, Su X, Shi R. Uncertainty of Acute Stroke Patients: A Cross-sectional Descriptive and Correlational Study. J Neurosci Nurs. 2018;50:238-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Byun E, Riegel B, Sommers M, Tkacs N, Evans L. Caregiving Immediately After Stroke: A Study of Uncertainty in Caregivers of Older Adults. J Neurosci Nurs. 2016;48:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rice V, Liu B. Personal resilience and coping with implications for work. Part I: A review. Work. 2016;54:325-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu Z, Zhou X, Zhang W, Zhou L. Factors associated with quality of life early after ischemic stroke: the role of resilience. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;26:335-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Varley BJ, Shiner CT, Johnson L, McNulty PA, Thompson-Butel AG. Revisiting Poststroke Upper Limb Stratification: Resilience in a Larger Cohort. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2021;35:280-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Guo L, Zauszniewski JA, Liu Y, Yv S, Zhu Y. Is resourcefulness as a mediator between perceived stress and depression among old Chinese stroke patients? J Affect Disord. 2019;253:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ong HL, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Sambasivam R, Fauziana R, Tan ME, Chong SA, Goveas RR, Chiam PC, Subramaniam M. Resilience and burden in caregivers of older adults: moderating and mediating effects of perceived social support. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dong Y, Guo ZN, Li Q, Ni W, Gu H, Gu YX, Dong Q; Chinese Stroke Association Stroke Council Guideline Writing Committee. Chinese Stroke Association guidelines for clinical management of cerebrovascular disorders: executive summary and 2019 update of clinical management of spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2019;4:176-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kuiper H, van Leeuwen CCM, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Post MWM. Measuring resilience with the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): which version to choose? Spinal Cord. 2019;57:360-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu L, Tan Y, Liu Y. Factor structure and psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale in a new employee population of China. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang D, Fan Z, Gao X, Huang W, Yang Q, Li Z, Lin M, Xiao H, Ge J. Illness uncertainty, anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma or cataract. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu Z, Zhang L, Cao Y, Xia W. The relationship between coping styles and benefit finding of Chinese cancer patients: The mediating role of distress. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;34:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Du R, Wang P, Ma L, Larcher LM, Wang T, Chen C. Health-related quality of life and associated factors in patients with myocardial infarction after returning to work: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li X, He L, Wang J, Wang M. Illness uncertainty, social support, and coping mode in hospitalized patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in a hospital in Shaanxi, China. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ahadzadeh AS, Sharif SP. Uncertainty and Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer: Moderating Role of Coping Styles. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zyga S, Mitrousi S, Alikari V, Sachlas A, Stathoulis J, Fradelos E, Panoutsopoulos G, Maria L. Assessing factors that affect coping strategies among nursing personnel. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28:146-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Foster K, Roche M, Delgado C, Cuzzillo C, Giandinoto JA, Furness T. Resilience and mental health nursing: An integrative review of international literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28:71-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Terrill AL, Schwartz JK, Belagaje S. Understanding Mental Health Needs After Mild Stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100:1003-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Crichton SL, Bray BD, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Patient outcomes up to 15 years after stroke: survival, disability, quality of life, cognition and mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1091-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Popa-Velea O, Diaconescu L, Jidveian Popescu M, Truţescu C. Resilience and active coping style: Effects on the self-reported quality of life in cancer patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2017;52:124-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ozawa C, Suzuki T, Mizuno Y, Tarumi R, Yoshida K, Fujii K, Hirano J, Tani H, Rubinstein EB, Mimura M, Uchida H. Resilience and spirituality in patients with depression and their family members: A cross-sectional study. Compr Psychiatry. 2017;77:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kirby JS, Butt M, Esmann S, Jemec GBE. Association of Resilience With Depression and Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1263-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fernandez-Araque A, Gomez-Castro J, Giaquinta-Aranda A, Verde Z, Torres-Ortega C. Mishel's Model of Uncertainty Describing Categories and Subcategories in Fibromyalgia Patients, a Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Guan T, Qan'ir Y, Song L. Systematic review of illness uncertainty management interventions for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:4623-4640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |