Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8915

Peer-review started: June 19, 2021

First decision: July 5, 2021

Revised: July 17, 2021

Accepted: August 6, 2021

Article in press: August 6, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 117 Days and 21.3 Hours

Trauma is one of the leading causes of death in the pediatric population. Bronchial rupture is rare, but there are potentially severe complications. Establishing and maintaining a patent airway is the key issue in patients with bronchial rupture. Here we describe an innovative method for maintaining a patent airway.

A 3-year-old boy fell from the seventh floor. Oxygenation worsened rapidly with pulse oxygen saturation decreasing below 60%, as his heart rate dropped. Persistent pneumothorax was observed with insertion of the chest tube. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed, which confirmed the diagnosis of bronchial rupture. A modified tracheal tube was inserted under the guidance of a fiberoptic bronchoscope. Pulse oxygen saturation improved from 60% to 90%. Twelve days after admission, right upper lobectomy was performed using bronchial stump suture by video-assisted thoracic surgery without complications. A follow-up chest radiograph showed good recovery. The child was discharged from hospital three months after admission.

A modified tracheal tube could be selected to ensure a patent airway and adequate ventilation in patients with bronchial rupture.

Core Tip: Tracheal intubation for traumatic bronchial rupture is difficult and complex. A modified tracheal intubation is a simple method to establish and maintain a patent airway for respiratory support in traumatic bronchial rupture. We treated a 3-year-old boy successfully using a modified tracheal tube which was inserted under the guidance of a fiberoptic bronchoscope.

- Citation: Fan QM, Yang WG. Use of a modified tracheal tube in a child with traumatic bronchial rupture: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(29): 8915-8922

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i29/8915.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8915

Trauma is one of the leading causes of death in the pediatric population, and most traumatic injuries in children are caused by blunt forces[1-3]. Thoracic injury is present in 10%-30% of all pediatric blunt injuries. Bronchial rupture is rare, but is life-threatening following blunt chest trauma. Mortality is reportedly to be close to 30% for those who arrive alive at the trauma bay[1,2,4-6]. More recently, mortality has decreased dramatically to approximately 9%, with most deaths occurring within the first 24 h[7]. Establishing and securing the airway is the key issue in patients with bronchial rupture. The classical techniques for ventilation include double lumen tubes (DLTs), bronchial blockers (BB), single-lumen endobronchial tubes, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and high-frequency ventilation. However, these techniques are not always available. We here report a case of traumatic bronchial rupture treated with a modified tracheal tube for respiratory support.

A 3-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital in a coma for 15 h after falling from a height.

The boy fell from the seventh floor, hitting a canopy on the fourth floor. He was unconscious. Blood was pouring from his mouth and nose. In the local hospital, pulse oxygen saturation was 60%. Chest computed tomography showed bilateral hemopneumothorax, as well as a large right pneumothorax. Following tracheal intubation and placement of a chest tube, pulse oxygen saturation increased to 90%. Subsequent chest X-ray showed a right pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema, and the right lung was compressed by 70%. The mediastinum was shifted to the left side. Bronchial rupture was suspected, and he was transferred to our Pediatric Inten

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The patient had a free personal and family history.

Vital signs were as follows: Temperature was 38.1 °C, heart rate was 132 bpm, respiratory rate was 40 breaths per minute (with mechanical ventilation), blood pressure was 64/34 mmHg, and pulse oxygen saturation was 95% (with mechanical ventilation). A few hours later, oxygenation worsened rapidly and pulse oxygen saturation decreased below 60%. He was in a shallow coma. His skin was slightly pale. His lower limbs were slightly bruised and his lips were ruddy. Bilateral pupils were equally large and round, with a diameter of about 2 mm. They were slow to react to light, and both eyeballs showed “sunset signs”. Pulmonary examination revealed subcutaneous emphysema in the right anterior chest wall and decreased breath sounds on the right side. On auscultation, rales were heard throughout the lungs. Extremity muscle strength examination could not be performed. His bilateral radial artery fluctuation was weakened.

Routine blood tests were as follows: white blood cells 19.45 × 109/L, neutrophils 88.2%, lymphocytes 6.7%, hemoglobin 121 g/L, platelets 147 × 109/L, and C-reactive protein 24.5 mg/L.

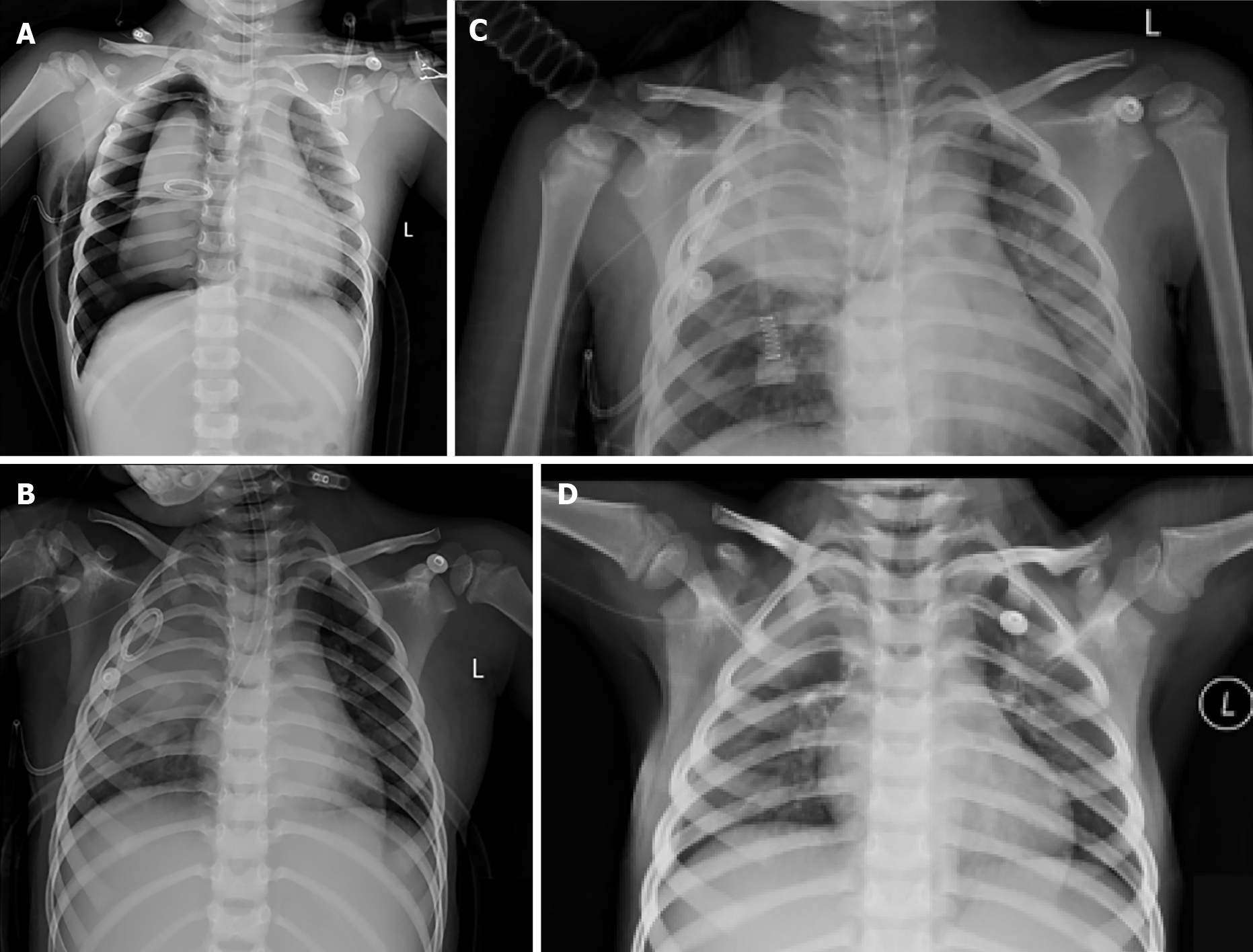

A chest radiograph revealed pulmonary contusion, right pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, combined with right first and second rib fractures and a right mediastinal hernia (Figure 1A). Other injuries included pelvic fractures and contusions of the liver and kidneys.

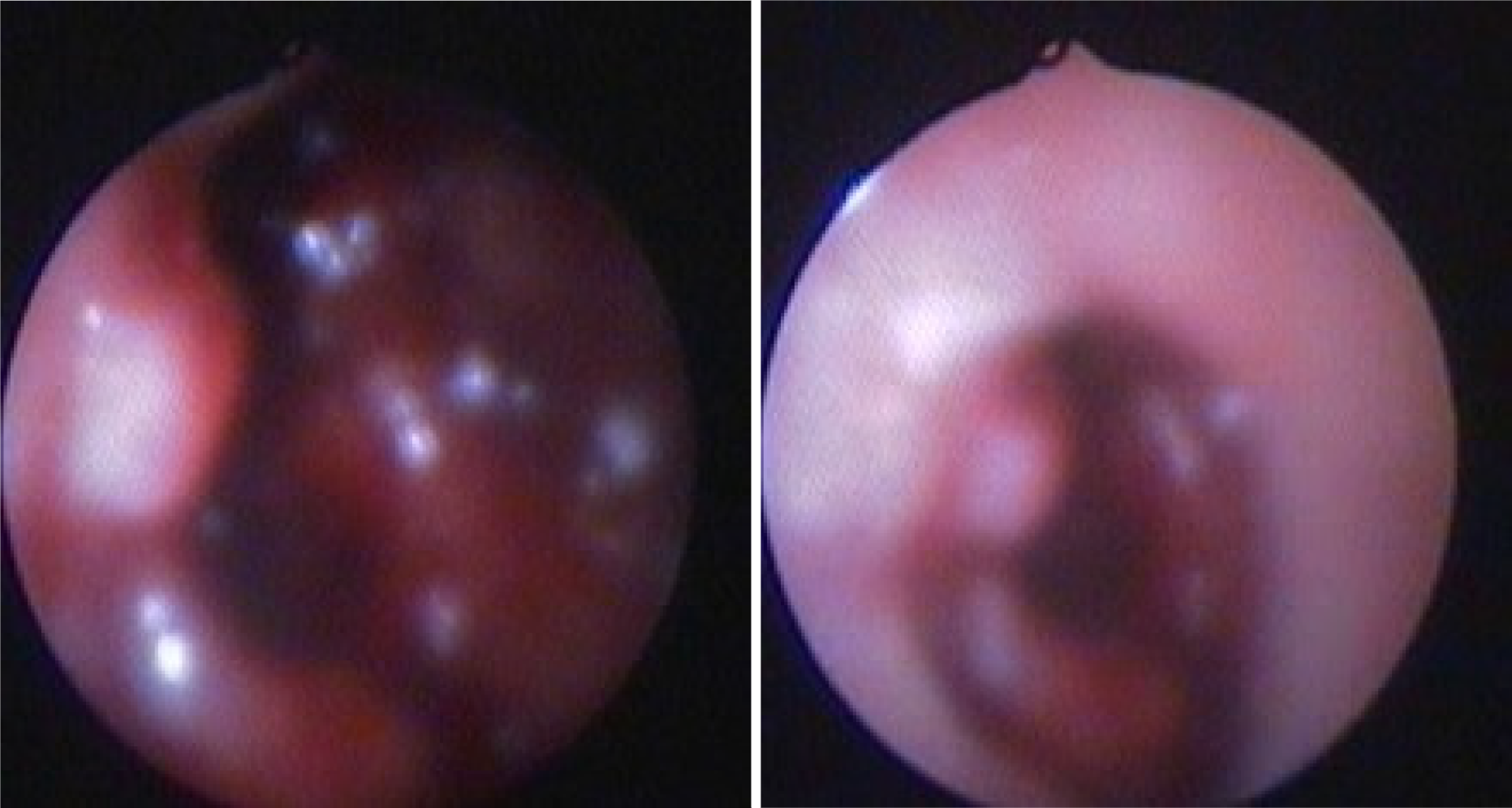

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed massive bloody secretions in the right main stem bronchus, especially the right upper lobe bronchus, where the bronchus opening was indistinguishable. Chest X-ray showed a persistent pneumothorax following insertion of the chest tube. Massive air and bloody fluid were seen in the thoracic drainage tube. Repeat fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed damage to the bronchus in the upper lobe of the right lung. The left bronchial tree was normal (Figure 2).

Based on fiberoptic bronchoscopy, the patient was diagnosed with bronchial rupture.

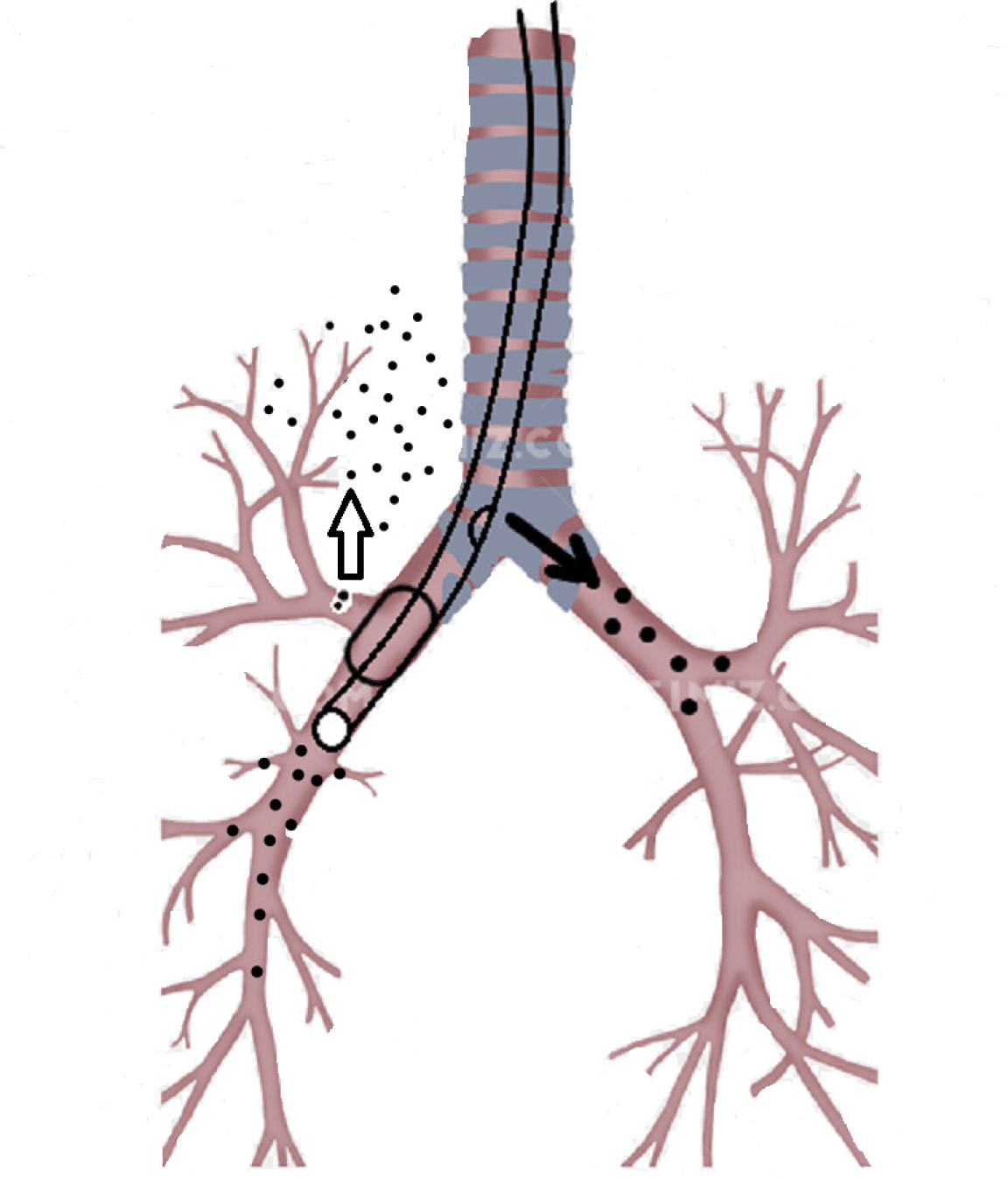

After active anti-shock therapy, the patient’s blood pressure returned to normal. Given his worsening respiratory distress, we managed to maintain a patent airway. However, the tracheal tube was mistakenly inserted into the right bronchus. Unex

Eleven days after admission, the modified tracheal tube was withdrawn into the trachea. Right upper lobectomy was performed using bronchial stump suture and video-assisted thoracic surgery on the 12th day.

Following surgical repair, the patient was weaned from the ventilator and successfully extubated on the 14th day, and given O2 therapy via wearing a simple mask with O2 flow at 3 L/min. Bronchoscopy was performed the day after surgery to confirm patent anastomosis permitting passage of the bronchoscope across it.

Nineteen days after admission, the child was transferred from PICU to neuro

Trauma to the chest leading to rupture of the main bronchus is rare with an incidence of approximately 0.7% to 2.8%[3,6,8-10]. Bronchial rupture is often fatal due to delayed diagnosis, difficulty in establishing an airway, and a high frequency of multi-organ damage[11-13]. Mortality was reported to be approximately 30%, but has recently dropped to about 9%[7]. Bronchial rupture is usually the consequence of a high-speed motor vehicle accident, but it can also be caused by crushing or twisting injuries or falling from a height[14,15]. It has been reported that the incidence of right bronchial rupture is higher than that of left bronchial rupture[3,16,17]. Kiser described fatal injuries to the right and left bronchus of 16% and 8%, respectively[18].

Priority should be given to maintain a patent airway for patients with bronchial rupture. Classic techniques include DLTs, BB, single-lumen endobronchial tubes, ECMO and high-frequency ventilation[3,19-22]. According to the literature, in children over 6-8 years of age, DLTs can be used for selective bronchial intubation[21]. But for a 3-year-old boy, its application is limited due to the unavailability of suitable size of DLTs. BB is a special device designed to be placed in the airway through or alongside the conventional endotracheal tube. However, BB could not be used for this child who was accompanied by a severe continuous air leak even after bilateral chest drainage, which can be a life-threatening problem[22]. Single-lumen endobronchial tubes with sufficient length are applied in neonates and infants when appropriate DLTs or BB are not available, although it is also associated with adverse effects, particularly atelectasis in the collapsed lung[21,22]. ECMO as an intraoperative support for pediatric emergency tracheobronchial injury has been described[23]. Advanced life support with ECMO may be required as a bridge to recovery and/or definitive surgical intervention if mechanical ventilatory support is not available. Hamilton et al[24] treated a patient with complicated tracheobronchial injury using venous-venous ECMO and performed delayed repair of a complicated traumatic airway disruption.

However, the ventilation techniques mentioned above are complex and require adequate knowledge, technical skills and special tubes, especially for infants and younger children. So they are often difficult to apply in areas where medical resources are scarce, leading to failure to provide timely and effective respiratory support. In this report, we present a case of traumatic bronchial rupture treated with a modified tracheal tube to maintain the airway. Using this method, we are able treat the patients who are deemed to be at high surgical risk due to comorbidities or the severity of the underlying disease or in units where qualified staff and advanced equipment are unavailable. This method has several advantages. First, no special equipment is needed, and operators do not need to undergo professional training; thus, it is easy to perform. Second, the segment of the injured bronchus was mechanically blocked, avoiding the further development of pneumothorax and compression of the lung caused by continuous air leakage. At the same time, other lobes and healthy lungs were fully inflated to avoid atelectasis. We used the same method to treat another child whose right bronchus was compressed by mediastinal tumor successfully.

Many reports have recommended that immediate primary repair is the preferred treatment for bronchial rupture[25,26]. Conservative management is only chosen for small lesions characterized by less than one third of the bronchial circumference, with easy ventilation, stable pneumomediastinum or subcutaneous emphysema, and the absence of respiratory distress and sepsis, which focuses on effective mechanical ventilation[3,9,12,15,27]. However, as early as 1971, Myers et al[28] proposed the idea of selective repair, that is, to defer repair until the local edema and inflammatory reaction have subsided. Jiang et al[29] also suggested that most cases of traumatic bronchial rupture in children do not require emergency surgery. For cases in a relatively stable condition, if the patient has sputum, fever or other pulmonary infection, this should be actively controlled and supportive treatment provided. Surgery can be delayed until the infection is controlled. Mortality decreases and repair success increases with extension of the delay[16,18]. Delayed repair of the bronchus can result in favorable outcomes as shown in the index case and in the literature[30-33]. If the patient’s hemodynamic status is unstable, postponing surgery is preferable[16]. In our case, a right upper lobectomy was performed 2 wk after diagnosis without complications.

In summary, priority should be given to ensuring a patent airway and adequate ventilation, although supporting ventilation in patients with bronchial rupture is a challenge for pediatricians in the PICU. A simple and modified tracheal tube might be the optimum choice when other techniques are unavailable.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bains L, Kambouri K S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wu RR

| 1. | Cay A, Imamoğlu M, Sarihan H, Koşucu P, Bektaş D. Tracheobronchial rupture due to blunt trauma in children: report of two cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:419-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Grant WJ, Meyers RL, Jaffe RL, Johnson DG. Tracheobronchial injuries after blunt chest trauma in children--hidden pathology. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1707-1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Slimane MA, Becmeur F, Aubert D, Bachy B, Varlet F, Chavrier Y, Daoud S, Fremond B, Guys JM, de Lagausie P, Aigrain Y, Reinberg O, Sauvage P. Tracheobronchial ruptures from blunt thoracic trauma in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1847-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ballouhey Q, Fesseau R, Benouaich V, Lagarde S, Breinig S, Léobon B, Galinier P. Management of blunt tracheobronchial trauma in the pediatric age group. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khan SA, Ekeoduru RA, Tariq S. Traumatic Tracheobronchial Laceration Causing Complete Tracheal Resection: Challenges of Anesthetic Management. A A Pract. 2018;11:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu CY, Chen TP, Liu YH, Ko PJ, Liu HP. Successful treatment of complicated tracheobronchial rupture using primary surgical repair. Chang Gung Med J. 2005;28:662-667. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shemmeri E, Vallières E. Blunt Tracheobronchial Trauma. Thorac Surg Clin. 2018;28:429-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ozdulger A, Cetin G, Erkmen Gulhan S, Topcu S, Tastepe I, Kaya S. A review of 24 patients with bronchial ruptures: is delay in diagnosis more common in children? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:379-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gaebler C, Mueller M, Schramm W, Eckersberger F, Vécsei V. Tracheobronchial ruptures in children. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hancock BJ, Wiseman NE. Tracheobronchial injuries in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:1316-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheaito A, Tillou A, Lewis C, Cryer H. Traumatic bronchial injury. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;27:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wood JW, Thornton B, Brown CS, McLevy JD, Thompson JW. Traumatic tracheal injury in children: a case series supporting conservative management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:716-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cunningham LC, Jatana KR, Grischkan JM. Conservative management of iatrogenic membranous tracheal wall injury: a discussion of 2 successful pediatric cases. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:405-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kelly JP, Webb WR, Moulder PV, Everson C, Burch BH, Lindsey ES. Management of airway trauma. I: Tracheobronchial injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;40:551-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wiener Y, Simansky D, Yellin A. Main bronchial rupture from blunt trauma in a 2-year-old child. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:1530-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kaptanoglu M, Dogan K, Nadir A, Gonlugur U, Akkurt I, Seyfikli Z, Gunay I. Tracheobronchial rupture: a considerable risk for young teenagers. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;62:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gwely NN. Blunt traumatic bronchial rupture in patients younger than 18 years. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:598-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kiser AC, O'Brien SM, Detterbeck FC. Blunt tracheobronchial injuries: treatment and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:2059-2065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brodsky JB. Lung separation and the difficult airway. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103 Suppl 1:i66-i75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maddali MM, Menon RG, Valliattu J. Traumatic bronchial rupture: implications of a delayed presentation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:875-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marraro GA. Selective bronchial intubation for one-lung ventilation and independent-lung ventilation in pediatric age: state of the art. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;22:543-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Reinoso-Barbero F, Sanabría P, Bueno J, Suso B. High-frequency ventilation for a child with traumatic bronchial rupture. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:183-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Suh JW, Shin HJ, Lee CY, Song SH, Narm KS, Lee JG. Surgical Repair of a Traumatic Tracheobronchial Injury in a Pediatric Patient Assisted with Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;50:403-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hamilton EC, Lazar D, Tsao K, Cox C, Austin MT. Pediatric tracheobronchial injury after blunt trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:554-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhao Y, Jiao J, Shan Z, Fan Q, Hu J, Zhang Q, Zhu X. Effective management of main bronchial rupture in patients with chest trauma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:447-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dib OS, Kasem EM. Bronchial injuries in children: single-center experience. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2014;22:1084-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Díaz C, Carvajal DF, Morales EI, Sangiovanni S, Fernández-Trujillo L. Right main bronchus rupture associated with blunt chest trauma: a case report. Int J Emerg Med. 2019;12:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Myers WO, Leape LL, Holder TM. Bronchial rupture in a child, with subsequent stenosis, resection, and anastomosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1971;12:442-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shouliang J, Zhengxia Pan, Hongbo Li, GangWang, Jiangtao Dai, Yong An, Yonggang Li, Chun Wu. Treatment of bronchial rupture after chest trauma in children. Chongqing Daxue Xuebao. 2018;43:269-273. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Jain V, Sengar M, Mohta A, Dublish S, Sethi GR. Delayed repair of posttraumatic bronchial transection. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:1609-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Beale P, Bowley DM, Loveland J, Pitcher GJ. Delayed repair of bronchial avulsion in a child through median sternotomy. J Trauma. 2005;58:617-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mahajan JK, Menon P, Rao KL, Mittal BR. Bronchial transection: delayed diagnosis and successful repair. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:389-392. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Shabb BR, Taha AM, Nabbout G, Haddad R. Successful delayed repair of a complete transection of the right mainstem bronchus in a five-year-old girl: case report. J Trauma. 1995;38:964-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |