Published online Oct 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8492

Peer-review started: April 1, 2021

First decision: May 27, 2021

Revised: May 28, 2021

Accepted: August 11, 2021

Article in press: August 11, 2021

Published online: October 6, 2021

Processing time: 180 Days and 3.9 Hours

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) may be caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Post-infection recovery-associated changes of HBV indicators include decreased hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) level and increased anti-HBsAg antibody titer. Testing to detect HBV DNA is conducted rarely but could detect latent HBV infection persisting after acute infection and prompt administration of treatments to clear HBV and prevent subsequent HBV-induced HCC deve

A 57-year-old male patient with abdominal pain who was diagnosed with primary HCC presented with an extremely high level (over 2000 ng/mL) of serum alpha-fetoprotein. Abdominal B-ultrasonography and computed tomography scan results indicated focal liver lesion and mild splenomegaly. Assessments of serological markers revealed a high titer of antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBcAg antibodies), an extremely high titer (1000 mIU/mL) of hepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBsAg antibodies, anti-HBs) and absence of detectible HBsAg. Medical records indicated that the patient had reported no history of HBV vaccination, infection or hepatitis. Therefore, to rule out latent HBV infection in this patient, a serum sample was collected then tested to detect HBV DNA, yielding a positive result. Based on the aforementioned information, the final diagnosis was HCC associated with hepatitis B in a compensated stage of liver dysfunction and the patient was hospitalized for surgical treatment.

A rare HCC case with high serum anti-HBsAg antibody titer and detectable HBV DNA resulted from untreated latent HBV infection.

Core Tip: Generally, hepatitis B surface antigen turning negative and the occurrence of hepatitis B surface antibody have been regarded as indicators of virus clearance and clinical recovery in hepatitis B patients. Here, we present a case of hepatis B virus (HBV) infection-associated hepatocellular carcinoma with extreme high titer of hepatitis B surface antibodies, up to 30396 mIU/mL, and failure to eliminate HBV. This case provides details of a diagnostic process for HBV infection-associated hepatocellular carcinoma that should be considered in patients with highly elevated titer of anti-HBs.

- Citation: Han JJ, Chen Y, Nan YC, Yang YL. Extremely high titer of hepatitis B surface antigen antibodies in a primary hepatocellular carcinoma patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(28): 8492-8497

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i28/8492.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i28.8492

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal mal

Although several anti-HBV drugs that inhibit HBV replication in the host have been approved globally for clinical use, not all patients with HBV have access to these drugs[4]. Even patients who have developed full immune responses against HBV still carry low virus numbers, with residual virus acting as a persistent source of HBV that may later engage in replication and reactivation that can eventually initiate development of HBV-associated HCC[5,6]. This article reports an HCC case with an extremely high anti-hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) antibody titer and latent HBV infection. The purpose of this work is to improve early HCC detection and help make a correct diagnosis to prevent development of HCC.

A 57-year-old male experiencing abdominal pain for 1 mo was admitted to our hospital in September 2020.

The patient developed epigastric pain 1 mo prior, which had worsened over the previous week.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

Review of the patient’s medical records indicated the patient had denied any history of HBV vaccination, HBV infection or hepatitis, as well as any history of blood transfusion, tattooing, intravenous drug abuse or family history of HBV infection.

Initial physical examination of the patient demonstrated mental clarity and good spirits. The patient had a dull complexion with no yellow staining on sclera or skin surfaces. Cardiopulmonary auscultation showed no abnormality. No tenderness or rebound tenderness were found across the entire abdomen, except for percussive pain in the liver area. Bowel sounds were normal, no edema was detected in the lower extremities and the patient tested negative for hepatic encephalopathy asterixis.

Results of laboratory testing assessments of serum marker levels were as follows: Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level greater than 2000.00 ng/mL (normal range: 0.89-8.78 ng/mL); negativity for both HBsAg and hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg); and anti-HBsAg antibody level greater than 1000.00 mIU/mL (normal range: < 10 mIU/mL), anti-HBeAg level of 0.04 S/Co (normal range: > 1.0 S/Co) and anti-HBcAg level of 9.06 S/Co (normal range: > 1.0 S/Co). Analysis of serum marker levels related to liver function indicated abnormal liver function, with alanine aminotransferase of 29 U/L (normal range: 9-50 U/L), aspartate transaminase of 65 U/L (normal range: 15-40 U/L), lactate dehydrogenase of 274 U/L (normal range: 120-250 U/L), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase of 213 U/L (normal range: 10 to 60 U/L), alkaline phosphatase of 145U/L (normal range: 45-125 U/L) and alpha hydroxy butyric acid deaminase of 224 U/L (normal range: 72-190 U/L).

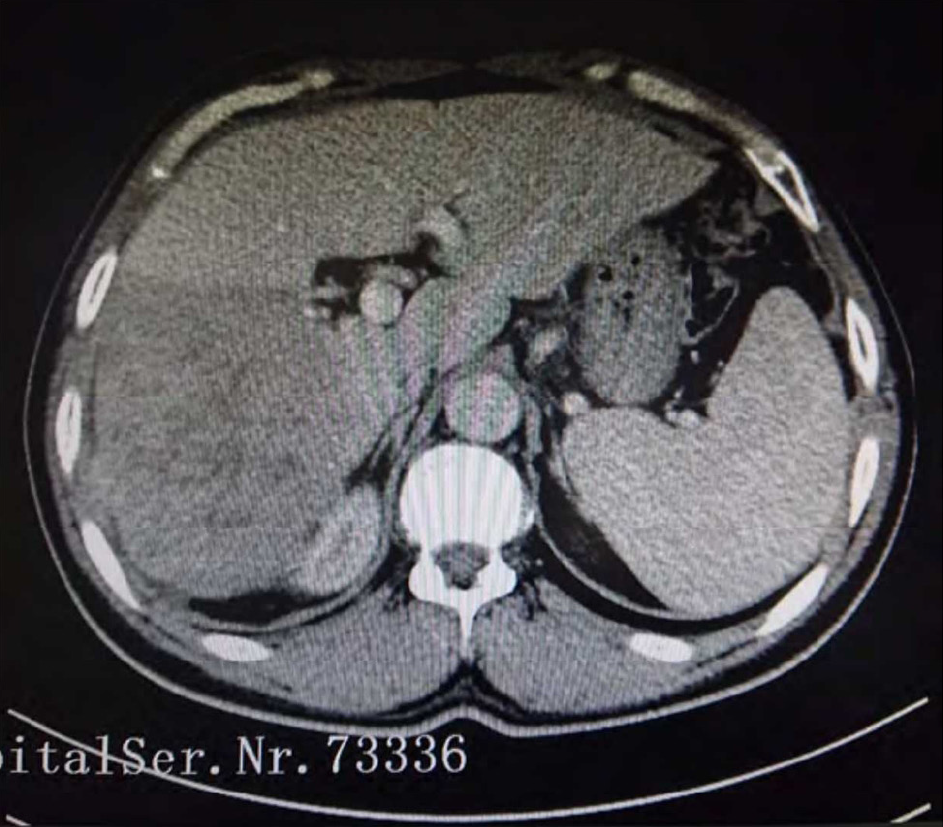

B-ultrasound scanning of the posterior abdomen revealed a hypoechoic solid mass in the right lobe of the liver with uneven density and irregular edges, a characteristic presentation of HCC. Moreover, mild splenomegaly was observed, which warranted further examination. Therefore, enhanced computed tomography (CT) scanning was conducted. CT scan results revealed an area of low-density soft tissue in a scanned plane within the upper abdomen, with mild density enhancement observed in the arterial phase and non-homogeneous density enhancement observed in the portal phase that together were suggestive of HCC accompanied by splenomegaly (Figure 1).

The anti-HBs concentration of the patient's serum was quantified by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay after dilution, which was finally confirmed to be 30,936 mIU/mL. Next, we selected a sample from this patient and ordinary anti-HBs-positive (200 mIU/mL) samples to conduct in vitro serological neutralization experiments along with HBsAg samples. The results showed that the effective neutralization rate of patients' serum was 88.8%, which was much higher than the 21.9% of ordinary anti-HBs-positive serum. It is concluded that the surface antibody of hepatitis B still has a strong protective effect in patients, and the patients may still be in the active period of virus replication.

Results of all serum marker-based assessments of HBV disease status in this patient revealed very high titers of anti-HBsAg and anti-HBc antibodies. Meanwhile, Novartis screening test results of patient blood indicated a positive HBV DNA result (detection sensitivity: 3 IU/mL), supporting categorization of the patient’s disease status as an Occult Hepatitis B virus infection (OBI); OBI status refers to an HBV patient’s serological state as characterized by a negative HBsAg detection result accompanied by detectable HBV DNA in serum and/or liver tissues and a positive anti-HBcAg antibody detection result with or without detected anti-HBsAg antibody[7].

Based on the aforementioned serological test results, this patient could be clearly classified as a seronegative OBI case. To sum up, the patient was diagnosed with primary HCC associated with hepatitis B in a compensated stage of liver cirrhosis.

After admission, the patient was given antivirus, liver protection, stomach protection, anti-infection and other treatment measures, and then transferred to other hospitals for surgical treatment.

The patient's abdominal pain was relieved prior to surgical treatment and HBV DNA was negative on review.

HCC, one of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies worldwide, occurs with an annual global incidence of greater than 626,000 cases per year. In China, the HCC mortality rate ranks second highest of all tumor-related mortality rates[8]. Clinical diagnosis of liver cancer is mainly based on ultrasound image-based examinations combined with assessments of serum AFP levels, with limitations of both assessments known to clinicians. Although AFP is the most widely used serum marker for HCC, its specificity as a marker for early diagnosis of HCC is 87%-93%, and its sensitivity is only 45.3%-62%[9]; its results need to be interpreted by experts, combined with analysis of imaging results. Meanwhile, ultrasound-based diagnosis is affected by operator skills, equipment sensitivity and patient characteristics that together decrease sensitivity to about 60%-80%[10]. Due to these limitations, CT scanning is considered a necessary step to confirm HCC diagnosis or to guide HCC clinical staging and treatment[11]. During CT plane-based scanning, HCC can be detected as regular or irregular low-density shadows, with occasional observations of isometric and high-density shadows (ruptured nodules). By contrast, enhanced CT scanning reveals typical “wash in and wash out” signs characterized by significantly enhanced signals in the enhanced arterial phase of tumor nodule scans and low signals in portal and delayed phase scans[12]. In this study, serum AFP level, ultrasound and CT results were all used together to confirm a diagnosis of HCC in this patient.

About 80% of primary liver cancers worldwide are associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection[13], in line with the scenario in China, whereby 85% of HCC patients test positive for HBV serological markers[3]. At least three different mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to development of HBV-related HCC. In the first proposed mechanism, HBV is not completely eliminated from infected patients, allowing low-level persistence in patient tissues of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA). Subsequently, cccDNA can integrate into the host genome and activate host genes controlling cell proliferation, while also triggering genomic instability that leads to inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and increased expression of cancer genes[14,15]. As another mechanism, chronic inflammation caused by HBV infection has been posited to lead to hepatocyte destruction and regeneration during the chronic phase of HBV infection, resulting in accumulation of genetic mutations conferring a cell growth advantage[16]. In yet another mechanism, the HBV-X open reading frame encodes a nonstructural protein, HBVx, with multiple functions in viral replication and oncogenic transformation, which may promote tumorigenesis as well[17].

As compared to indicators used for HBV diagnosis, hepatitis B serological markers are generally used to guide disease prognosis. Based on the fact that HBsAg is translated from HBV cccDNA transcripts, HBsAg levels are thought to reflect the level of cccDNA in HBV-infected hepatocytes as evidence of active HBV infection. Indeed, detection tests based on HBV cccDNA have already been used effectively to detect HBV DNA in both acute and chronic hepatitis B patients as well as in asymptomatic carriers[18]. In fact, for the majority of acute hepatitis B patients, HBsAg levels become undetectable after clinical recovery from HBV, while persistence of detectable HBsAg levels for 6 mo or longer is a sign of disease progression to a chronic hepatitis B infection phase. Meanwhile, anti-HBsAg antibodies are capable of neutralizing HBV and thus play a protective role against HBV infection. Therefore, a change in HBsAg detection status to undetectable along with detection of serum anti-HBsAg antibodies are viewed together as indicators of virus clearance and clinical recovery after hepatitis B infection. However, in the unique case presented here, HBV DNA was still detectable at a high level in the patient in spite of indicators of clinical recovery (both an undetectable HBsAg level and high-level anti-HBsAg antibody titer). Thus, taken together all findings here pointed to active HBV replication in this patient that may have led to development of HCC, as consistent with the proposed diagnosis of OBI[19].

The prevalence of OBI varies greatly across the world and across patient populations, with higher rates reported in Asia. The prevalence of OBI is higher in patients with chronic liver disease and may be as high as 40% to 75% in those with HBsAg-negative HCC. It is almost equivalent to a persistent HBsAg-positive HCC patient[20]. Although causative factors of OBI remain unclear, in OBI cases a strong anti-HBsAg antibody response in vivo may result in binding of antibodies to HBsAg to form immune complexes that are rapidly removed from circulation, resulting in low serum HBsAg levels. Concurrently, partial or full HBV genomes may integrate into genomic DNA of hepatocytes to support constant HBV replication and release of HBV DNA into the circulation in spite of an abundance of anti-HBsAg antibodies. Such persistent low-level viral replication may then act as a source of escape mutants that are not neutralized by host anti-HBsAg antibodies that are also undetectable using current HBsAg assays[21]. Based on this scenario, it is possible that the patient here is currently infected with a rare HBV subtype with one or more unique mutations that cannot be detected using current HBsAg detection reagents. We are currently sequencing the full genome of HBV DNA from this patient to confirm this speculation. Meanwhile, in a recent report, a meta-analysis of 44,553 patients suggested that in HBsAg-negative patients with chronic liver disease, anti-HBc positivity is strongly associated with the presence of HCC, which suggested that more factors may be involved in development of HCC in this group of patients[22].

Here, a case of HBV infection-associated primary HCC is described with an extremely high serum titer of hepatitis B surface antibodies and detectable HBV DNA. Based on literature review and case findings presented here, HBV infection-associated HCC can occur in “clinically recovered” HBV patients with high serum levels of anti-HBsAg and undetectable HBsAg levels. To prevent later HCC development in such patients, routine screening for HBV DNA is required and testing should be expanded to include additional hepatitis B serum markers, in order to improve early HCC detection and prevent development of HCC.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Bain V, Gumbs A, Kumar SKY S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Yuen MF, Chen DS, Dusheiko GM, Janssen HLA, Lau DTY, Locarnini SA, Peters MG, Lai CL. Hepatitis B virus infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Venook AP, Papandreou C, Furuse J, de Guevara LL. The incidence and epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global and regional perspective. Oncologist. 2010;15 Suppl 4:5-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 626] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang M, Wang Y, Feng X, Wang R, Zeng H, Qi J, Zhao H, Li N, Cai J, Qu C. Contribution of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus to liver cancer in China north areas: Experience of the Chinese National Cancer Center. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;65:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seeger C, Mason WS. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology. 2015;479-480:672-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen Y, Tian Z. HBV-Induced Immune Imbalance in the Development of HCC. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ali A, Abdel-Hafiz H, Suhail M, Al-Mars A, Zakaria MK, Fatima K, Ahmad S, Azhar E, Chaudhary A, Qadri I. Hepatitis B virus, HBx mutants and their role in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10238-10248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Raimondo G, Locarnini S, Pollicino T, Levrero M, Zoulim F, Lok AS; Taormina Workshop on Occult HBV Infection Faculty Members. Update of the statements on biology and clinical impact of occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2019;71:397-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, Kamath PS. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70:151-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1382] [Cited by in RCA: 2286] [Article Influence: 381.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lok AS, Sterling RK, Everhart JE, Wright EC, Hoefs JC, Di Bisceglie AM, Morgan TR, Kim HY, Lee WM, Bonkovsky HL, Dienstag JL; HALT-C Trial Group. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin and alpha-fetoprotein as biomarkers for the early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:493-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 450] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tzartzeva K, Obi J, Rich NE, Parikh ND, Marrero JA, Yopp A, Waljee AK, Singal AG. Surveillance Imaging and Alpha Fetoprotein for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1706-1718.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 638] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 115.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Forner A, Vilana R, Ayuso C, Bianchi L, Solé M, Ayuso JR, Boix L, Sala M, Varela M, Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Diagnosis of hepatic nodules 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis: Prospective validation of the noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 727] [Article Influence: 42.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2800] [Cited by in RCA: 4092] [Article Influence: 584.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 13. | Wang FS, Fan JG, Zhang Z, Gao B, Wang HY. The global burden of liver disease: the major impact of China. Hepatology. 2014;60:2099-2108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 985] [Cited by in RCA: 942] [Article Influence: 85.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 14. | Shlomai A, de Jong YP, Rice CM. Virus associated malignancies: the role of viral hepatitis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;26:78-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cevik D, Yildiz G, Ozturk M. Common telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas from different geographical locations. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Han YF, Zhao J, Ma LY, Yin JH, Chang WJ, Zhang HW, Cao GW. Factors predicting occurrence and prognosis of hepatitis-B-virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4258-4270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Salerno D, Chiodo L, Alfano V, Floriot O, Cottone G, Paturel A, Pallocca M, Plissonnier ML, Jeddari S, Belloni L, Zeisel M, Levrero M, Guerrieri F. Hepatitis B protein HBx binds the DLEU2 LncRNA to sustain cccDNA and host cancer-related gene transcription. Gut. 2020;69:2016-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kao JH. Diagnosis of hepatitis B virus infection through serological and virological markers. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;2:553-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Allain JP. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. Transfus Clin Biol. 2004;11:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mak LY, Wong DK, Pollicino T, Raimondo G, Hollinger FB, Yuen MF. Occult hepatitis B infection and hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, virology, hepatocarcinogenesis and clinical significance. J Hepatol. 2020;73:952-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yip TC, Wong GL. Current Knowledge of Occult Hepatitis B Infection and Clinical Implications. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:249-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coppola N, Onorato L, Sagnelli C, Sagnelli E, Angelillo IF. Association between anti-HBc positivity and hepatocellular carcinoma in HBsAg-negative subjects with chronic liver disease: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |