Published online Sep 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8199

Peer-review started: April 28, 2021

First decision: June 6, 2021

Revised: June 17, 2021

Accepted: August 31, 2021

Article in press: August 31, 2021

Published online: September 26, 2021

Processing time: 145 Days and 18.6 Hours

Madelung’s disease (MD) is a rare disorder of lipid metabolism, characterized by the growth of unencapsulated masses of adipose tissue symmetrically deposited around the neck, shoulders, or other sites around the body. Its pathological mechanism is not yet known. One of the most common comorbidities in MD patients is liver disease, especially chronic alcoholic liver disease (CALD); however, no reports exist of acute kidney injury (AKI) with MD.

We report a 60-year-old man who presented with complaint of edema in the lower limbs that had persisted for 3 d. Physical examination showed subcutaneous masses around the neck, and history-taking revealed the masses to have been present for 2 years and long-term heavy drinking. Considering the clinical symptoms, along with various laboratory test results and imaging characteristics, a diagnosis was made of MD with acute exacerbation of CALD and AKI. The patient was treated with liver function protection and traditional Chinese medicine, without surgical intervention. He was advised to quit drinking. After 10 d, the edema had subsided, renal function indicators returned to normal, liver function significantly improved, and size of subcutaneous masses remained stable.

In MD, concomitant liver or kidney complications are possible and monitoring of liver and kidney functions can be beneficial.

Core Tip: Madelung’s disease (MD) is a rare disorder of lipid metabolism, characterized by symmetrically deposited unencapsulated masses of adipose tissue. Liver disease is one of the most common comorbidities of MD, but no reports exist of comorbid kidney disease. Here, we report a male patient, 60 years of age, diagnosed as MD with acute exacerbation of chronic alcoholic liver disease and acute kidney injury. This case reminds us that in the diagnosis and treatment of MD, in addition to the known liver comorbidities, we also need to consider renal function in order to detect any concomitant kidney disease.

- Citation: Wu L, Jiang T, Zhang Y, Tang AQ, Wu LH, Liu Y, Li MQ, Zhao LB. Madelung’s disease with alcoholic liver disease and acute kidney injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(27): 8199-8206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i27/8199.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8199

Madelung’s disease (MD) - a rare benign tumor of fat tissue, and also known by the names of multiple symmetric lipomatosis, benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome - was first reported by Brodie in 1846[1]. Since then, the MD cases reported show the characteristics of progressive symmetrical deposition of unencapsulated adipose tissue in the neck, upper back, shoulders, or other bodily areas. The causes of MD have not been completely investigated, but the rudimentary knowledge is that alcoholism is associated with its onset[2]. Moreover, among the multiple comorbidities of MD that have been reported, chronic alcoholic liver disease (CALD) is one of the most common types, in line with the associated alcohol abuse, but there have been no reports of MD with acute kidney injury (AKI).

Herein, we report a MD patient with CALD and AKI, to share our clinical experience of the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

A 60-year-old man presented to the Department of Nephrology, complaining of severe edema in the lower limbs.

The patient reported that his symptoms had started 3 d prior, accompanied by a decrease of 24 h urine output (estimated to about 800 mL/d). He had self-administered furosemide but achieved no relief of his symptoms, and noted that the edema was gradually increasing.

The patient denied any relevant previous medical history. During the physical examination, we found a symmetrical soft mass on the neck, which produced no pain. The patient reported that the neck mass had appeared 2 years prior and had gradually increased in size over time; he stated that he had not received any particular treatment for it. However, he specified that in the past month the mass had grown in a much more significant manner than before.

The patient had a > 10-year history of severe alcoholism (about 200 mL liquor per day). He reported that in the past month his alcohol consumption had increased significantly, due to work failures. His family history was unremarkable.

The patient was of medium size, with body mass index of 26.22 kg/m2. Both lower extremities had moderate to severe pitting edema, with normal skin temperature and without ulcers or inflammatory exudation. The skin and mucous membranes showed no signs of jaundice or cyanosis. Rash, liver palms and spider moles were also not present. However, there were subcutaneous masses around the neck, located symmetrically; these were soft, immovable, without tenderness, and with clear boundaries (Figure 1). There were no signs of moon face, hirsutism, or purple striae. The liver and spleen were not palpated under the rib and shifting dullness was negative. The remaining physical examinations showed no obvious abnormalities.

Serum test results showed elevated liver enzymes (including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and alkaline phosphatase), decreased serum total proteins and albumin, increased blood uric acid, and markers of impaired renal function. Blood routine findings suggested moderate anemia. Tests for coagulation indices, tumor markers, immunoglobulin light chains, thyroid hormones and autoimmune antibodies revealed no abnormalities. Liver fibrosis indices showed increased levels (Table 1).

| Variable | At admission | After 10 d | Reference range |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 118 U/L | 37 U/L | 9-50 U/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 112 U/L | 43 U/L | 15-40 U/L |

| γ-glutamyl transferase | 1103 U/L | 502 U/L | 10-60 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 159 U/L | 161 U/L | 45-125 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 26.2 μmol/L | 18.7 μmol/L | 5.1-28.0 μmol/L |

| Creatinine | 133.6 μmol/L | 96.8 μmol/L | 57-111 μmol/L |

| Uric acid | 561 μmol/L | 448 μmol/L | 202-416 μmol/L |

| Urea nitrogen | 17.99 mmol/L | 5.52 mmol/L | 3.6-9.5 mmol/L |

| B-type natriuretic peptide | 902.3 pg/mL | 325.6 pg/mL | 0-125 pg/mL |

| Serum total protein | 57.9 g/L | 60.1 g/L | 65-85 g/L |

| Albumin | 34.9 g/L | 26.9 g/L | 40-55 g/L |

| Albumin/globulin | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.2-2.4 |

| Leukocyte count | 3.29 × 109/L | 3.49 × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 × 109/L |

| Erythrocyte count | 2.38 × 1012/L | 2.4 × 1012/L | 4.3-5.8 × 1012/L |

| Platelet count | 72 × 109/L | 84 × 109/L | 100-300 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 80 g/L | 78 g/L | 130-175 g/L |

| Reticulocyte percentage (%) | 6.2 | 4.7 | 0.5-1.5 |

| Liver fibrosis indicators | |||

| Serum hyaluronic acid | 473.3 ng/mlL | - | 0-100 ng/mL |

| Laminin | 70.91 ng/mlL | - | 0.51-50 ng/mL |

| Collagen IV | 39.4 mg/mL | - | 0.021-30 mg/mL |

| Cholyglycine | 13.98 mg/mL | - | 0-2.7 mg/mL |

| Amino terminal procollagen type III peptide | 34.63 ng/mL | 0.021-30 ng/mL |

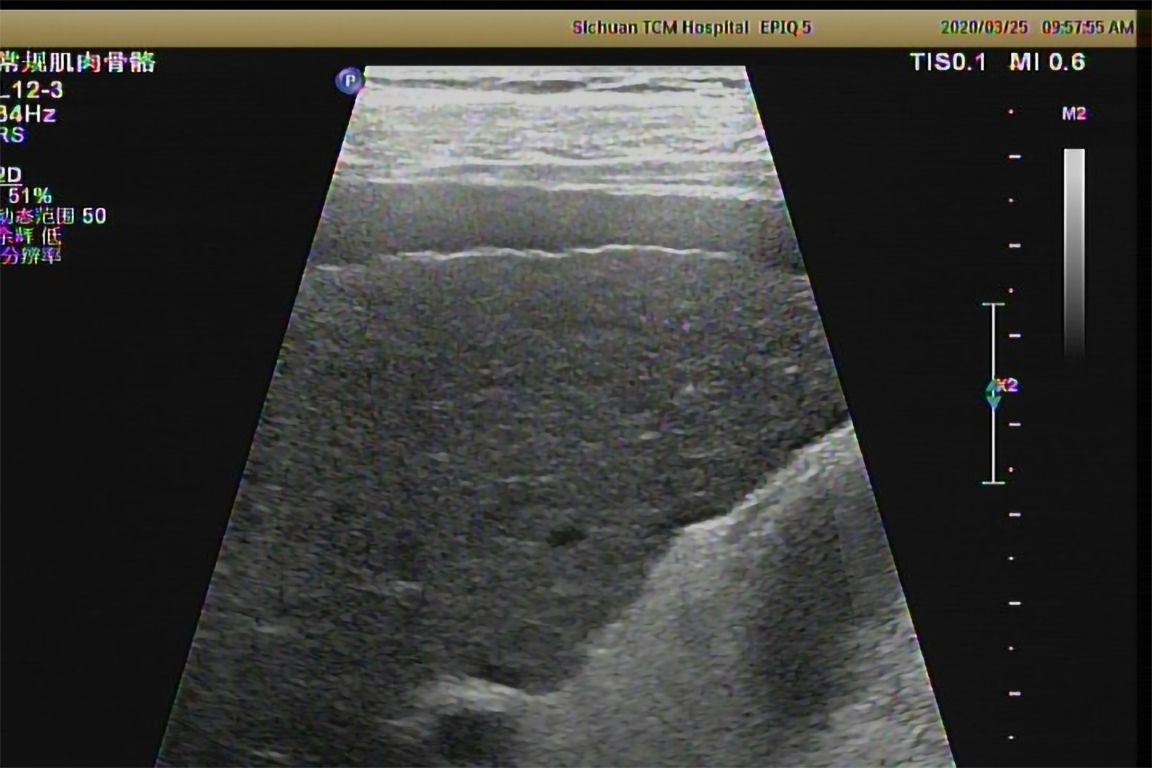

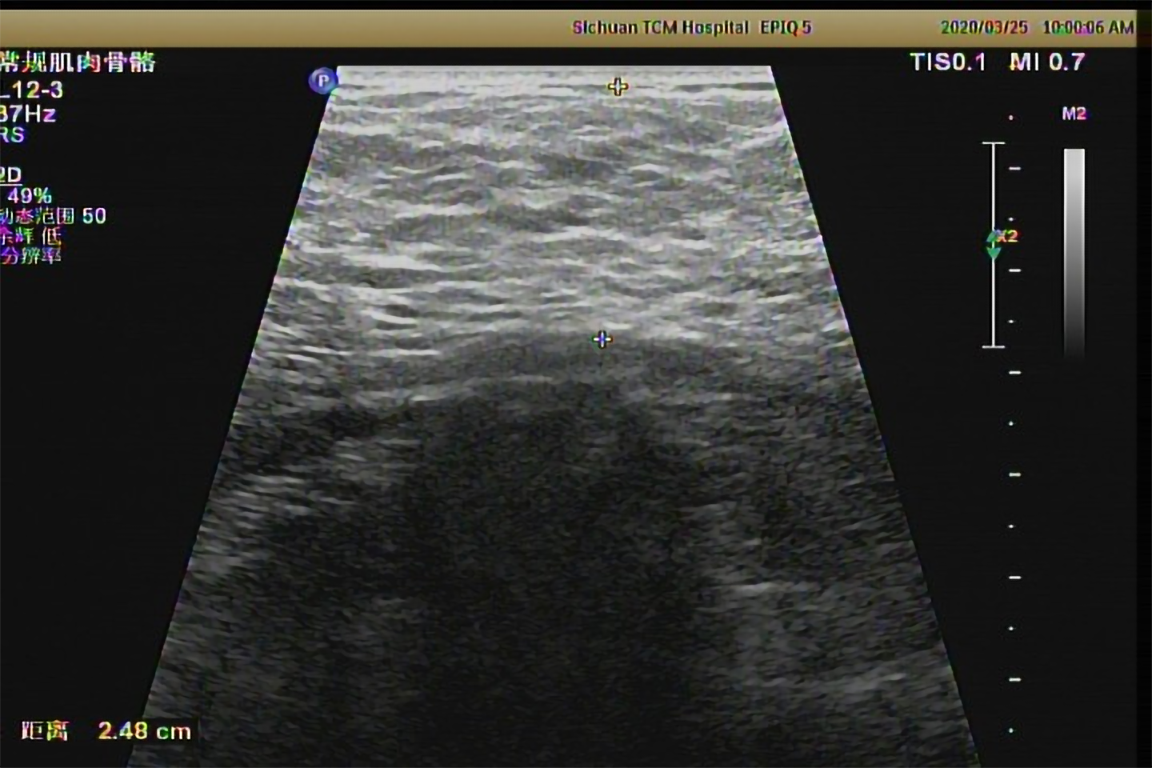

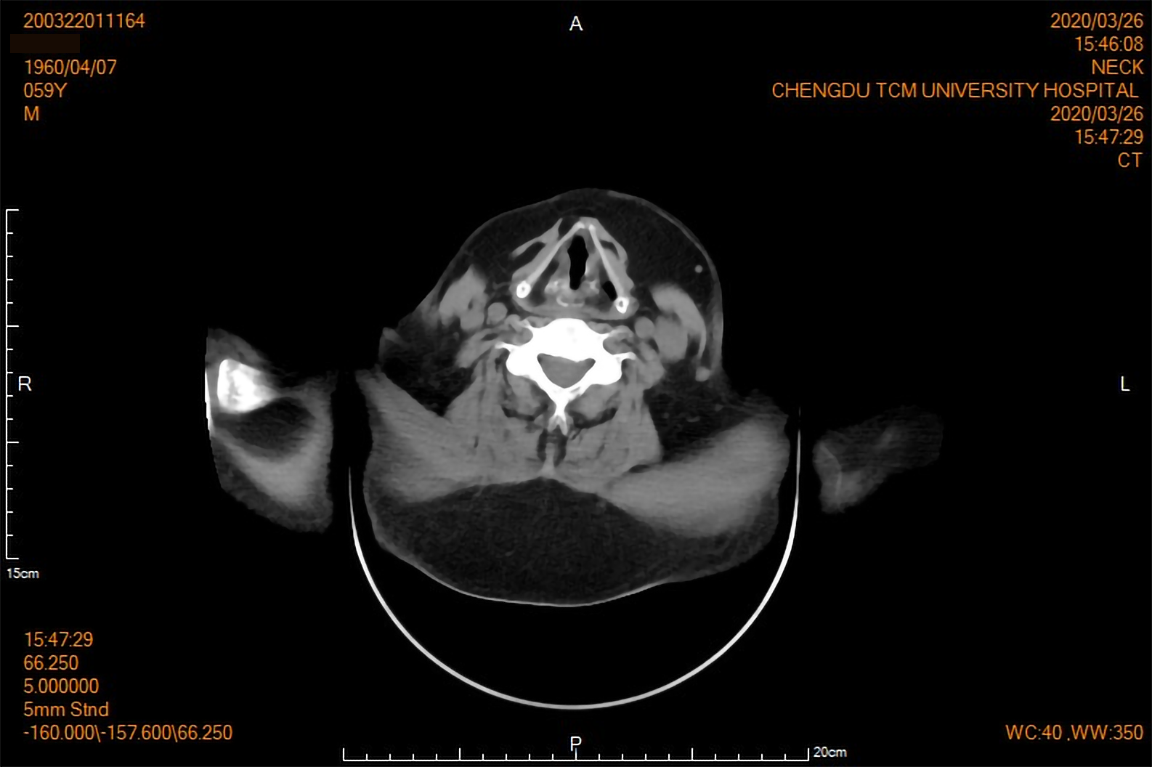

Two-dimensional ultrasound examination showed chronic liver damage (Figure 2) and peritoneal effusion. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan also showed peritoneal effusion, and was negative for splenomegaly and portal vein expansion. The imaging findings, considered along with the patient’s long-term drinking history, indicated acute exacerbation of CALD. The clinical appearance of symmetrically subcutaneous masses around the neck was compatible with the characteristics of type I MD, which was confirmed by the two dimensional ultrasound (Figure 3) and CT (Figure 4).

To further screen out other possible causes of liver damage, we measured viral hepatitis- related antigens and antibodies. The results showed that the patient was negative for hepatitis. The blood vessel color Doppler ultrasound results for both lower extremities were unremarkable.

According to the patient's physical examination, ultrasound and CT imaging findings, combined with the patient's history of heavy drinking, the diagnosis of MD can be supported and further pathological diagnosis should be performed. Surgery is the first treatment for MD. However, the patient has no symptoms of pressure, such as dyspnea, so surgical treatment may not be considered for the time being, and medical treatment is recommended as the main treatment. Complications will need to be actively treated to prevent other organs’ damage and delay progression of the disease. Alcohol abstinence will be of great value for delaying the growth of lumps and delaying the progression of the disease.

The main complaint of the patient was pitting edema affecting both lower extremities, which prompted his visit to the Department of Nephrology. After the examination, the patient was diagnosed with AKI. After inquiring about the medical history, medication history, and laboratory tests, causes of prerenal, obstructive and drug-induced injury were ruled out. We considered that it may be related to heavy drinking, metabolic disorders combined with MD, or relatively insufficient blood volume. However, there have been no reports of MD combined with AKI in general or alcohol-related AKI in particular. The patient’s current kidney damage was still in the early stage, and renal function could be improved by mitigating the factors of kidney damage. No blood purification treatment was required. Therefore, alcohol abstinence was the primary recommended treatment. During that treatment process, the patient must be closely monitored for changes in urine output, body weight and renal function indicators, and the treatment plan must be adjusted in a timely manner.

MD with acute exacerbation of CALD and AKI, and moderate anemia

As the patient had no dyspnea, dysphagia or neck movement disorders, surgical treatment and subsequent pathological diagnosis were deemed unnecessary. The patient was treated using a combination strategy of liver function protection (reduced glutathione, compound diisopropylamine dichloroacetate injection, and bicyclol tablets) and traditional Chinese medicine, and was advised to stop drinking.

After 10 d, the patient’s edema had subsided, his liver function had significantly improved, and his levels of renal function indices had returned to normal (Table 1). His subcutaneous masses had remained the same in size. He was continued on medications for alcohol withdrawal and liver function protection.

MD is a rare disorder of lipid metabolism, featuring abnormal accumulation of adipose tissue. Among Italians, the incidence rate is 1/25000, having a higher prevalence in the Mediterranean region; it is less widespread in Asia[3]. In general, the disease is more common among middle-aged adults (30-60-years-old), affecting males with a history of chronic alcoholism especially, who account for more than 80% of the patients[4]. The patient presented herein was a 60-year-old male with a > 10-year history of alcoholism (approximately 200 mL liquor per day).

The diagnosis of MD is based on clinical history, physical signs, and findings from routine physical and imaging examinations; biopsy can be helpful for further differential diagnosis. The main signs of this disease are progressive, symmetrical and painless subcutaneous fatty masses. According to the clinical manifestations and the distribution of fatty masses, MD can be divided into two types[5]. Type I occurs mainly in males and is characterized by fat deposition in the upper body, including the parotid glands (the “hamster cheeks”), cervical region (the “horse collar”), posterior neck (the “buffalo hump”), submental region (the “Madelung collar”), shoulders, and proximal upper limbs. Type II shows no sex-specific prevalence and is characterized by diffuse fat deposits in the abdomen and thighs, giving patients the appearance of simple obesity. In addition, fat deposits may also occur in rare parts, such as breasts[6], tongue[7], and scrotum[8]. The fat tissue of the patient described herein was mainly deposited around the neck, supporting the diagnosis of type I MD.

The fatty masses of either type of MD are non-encapsulated and can eventually reach a very large size. If the fat deposits compress or infiltrate important blood vessels, nerves, throat, trachea and bronchi, it can cause a series of symptoms, consisting of mediastinal syndrome, tracheobronchial obstruction, dysphagia, dysphonia, hoarseness, or limitations of neck mobility[9]. The appearance of these symptoms is often what prompts patients to visit a hospital or undergo surgical treatment. The present patient did not experience symptoms of compression or infiltration, so he did not require surgery.

MD patients have multiple comorbidities, encompassing metabolic disorders, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hyperuricemia, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, etc. The present case was diagnosed with hypertension and hyperuricemia, without diabetes, hyperlipidemia or abnormalities in thyroid function.

Considering the long-term history of alcoholism, significant changes in liver enzymes and imaging findings for the present case, the diagnosis of MD with acute exacerbation of CALD was confirmed. MD is more prevalent in patients with long-term alcohol abuse, and the resultant alcoholic liver injury can cause other liver diseases subsequently. Ballestri et al[10] proposed the neck-liver axis concept, pointing out that fat accumulation in the neck-dorsocervical area is a risk factor for liver inflammation and fibrosis. Vassallo et al[11] reported a male case of MD that was complicated with acute alcoholic hepatitis; the patient had presented with jaundice, ascites, breast enlargement and hepatosplenomegaly. Gao et al[12] reported a male case of MD complicated with chronic alcoholic cirrhosis, and Iglesias et al[13] reported a 50-year-old male patient diagnosed with MD and alcoholic liver disease, who presented with edema, ascites and significant hepatosplenomegaly. In addition to these complications, alcoholic fatty liver[14] and hepatocellular carcinoma[15] have also been reported in MD patients. A survey involving 59 patients with MD found that 25% of patients had liver disease complications[4]. These cases should serve to remind us to put in extra efforts in the detection of liver function in patients with MD.

In addition, our patient was also diagnosed with AKI. To our knowledge, there are no reports of a similar kidney-related comorbidity in the literature to date. After searching for relevant information, our team considered that the patient’s AKI may be related to the following three aspects: (1) Intake of a large amount of alcohol has the potential to damage the kidneys; (2) The metabolic disorder associated with MD may cause a decline in renal function; and (3) Severe edema can lead to insufficient (ineffective) blood circulation, causing prerenal AKI. However, whether there is an inevitable connection between kidney disease and MD and alcoholism needs to be confirmed by an observational study of adequately-powered clinical data.

The pathogenesis of MD remains unknown. Currently, a major hypothesis holds that the tumor-like proliferation of brown adipose tissue is the basic mechanism of MD onset[9], which is related to the reduction of lipolysis induced by decreases in the number or activity of β-adrenergic receptors. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction[16] (e.g., loss of the respiratory chain and decreased cytochrome C oxidase activity) and gene mutations in mitochondrial DNA (e.g., MTTK c.8334A>G mutation)[17] also contribute to the occurrence and development of MD. Although accurate causes are unknown, alcoholism is a definite contributor to the progression of MD, which can cause mitochondrial dysfunction or DNA mutations, and can interfere with the adrenergic system, thereby reducing lipolysis and promoting fat deposition[18].

MD is a benign disease and surgical therapy, including lipectomy and liposuction, is the main and currently only effective treatment. However, recurrence after surgery is another concern, with an average rate of 39% in surgically-treated patients; moreover, the recurrence rate is higher among those treated with liposuction than those treated with lipectomy[4]. Other therapies, such as local injection of lipolytic drugs and oral β-adrenergic receptor agonists (salbutamol)[19], have been applied and investigated, but the clinical efficacy remains unclear, due to lack of large-scale clinical trials. Considering the relationship between MD and alcoholism, alcohol cessation is considered as a robust treatment method. Regardless of the fact that alcohol cessation cannot reverse the progression of MD, it truly can help to reduce the recurrence after surgery and the deposition of fatty tissue[2]. We did not conduct a surgical treatment on our patient, as he was asymptomatic. He was prescribed alcohol cessation, along with liver protective drugs and traditional Chinese medicine. To a certain extent, this case shows that traditional Chinese medicine has a positive role in the treatment, but more clinical trials are needed to confirm such.

In summary, with regard to diagnosis and treatment of MD, clinicians must intensively monitor liver function indicators, and distinguish viral hepatitis from other liver diseases when patients have liver function damage and an absolute diagnosis has not yet been made; this is necessary to improve the accuracy of diagnosis, formulate a comprehensive treatment plan, and maximize therapeutic effect. Finally, to verify whether there is an inevitable connection between AKI and MD, more clinical observations are needed.

The authors are grateful to the patient for allowing publication of his case details.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dumitrascu DL, Skrypnyk I S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Brodie BC. Clinical Lectures on Surgery. Delivered at St. Georgeʼs Hospital. Am J Med Sci. 1846;11:437. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gao Y, Hu JL, Zhang XX, Zhang MS, Lu Y. Madelung's Disease: Is Insobriety the Chief Cause? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:1208-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Enzi G, Biondetti PR, Fiore D, Mazzoleni F. Computed tomography of deep fat masses in multiple symmetrical lipomatosis. Radiology. 1982;144:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pinto CI, Carvalho PJ, Correia MM. Madelung's Disease: Revision of 59 Surgical Cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017;41:359-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Enzi G. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: an updated clinical report. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63:56-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jang JH, Lee A, Han SA, Ryu JK, Song JY. Multiple Symmetric Lipomatosis (Madelung's Disease) Presenting as Bilateral Huge Gynecomastia. J Breast Cancer. 2014;17:397-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kang JW, Kim JH. Images in clinical medicine. Symmetric lipomatosis of the tongue. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | da Costa JN, Gomes T, Matias J. Madelung Disease Affecting Scrotal Region. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;78:73-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Enzi G, Busetto L, Sergi G, Coin A, Inelmen EM, Vindigni V, Bassetto F, Cinti S. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: a rare disease and its possible links to brown adipose tissue. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ballestri S, Lonardo A, Carulli L, Ricchi M, Bertozzi L, De Santis G, Bondi M, Loria P. The neck-liver axis. Madelung disease as further evidence for an impact of body fat distribution on hepatic histology. Hepatology. 2008;47:361-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vassallo GA, Mirijello A, Tarli C, Rando MM, Antonelli M, Garcovich M, Zocco MA, Sestito L, Mosoni C, Dionisi T, D'Addio S, Tosoni A, Gasbarrini A, Addolorato G. Madelung's disease and acute alcoholic hepatitis: case report and review of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:6272-6276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gao H, Xin ZY, Yin X, Zhang Y, Jin QL, Wen XY. Madelung disease: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iglesias L, Pérez-Llantada E, Saro G, Pino M, Hernández JL. Benign symmetric lipomatosis (Madelung's disease). Eur J Intern Med. 2000;11:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Karashima S, Yoneda T. Madelung disease in a 58-year-old man. CMAJ. 2019;191:E48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Casas Deza D, Gotor Delso J, Bernal Monterde V. Madelung's disease in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:645-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ko MJ, Chiu HC. Madelung's disease and alcoholic liver disorder. Hepatology. 2010;51:1466-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Perera U, Kennedy BA, Hegele RA. Multiple Symmetric Lipomatosis (Madelung Disease) in a Large Canadian Family With the Mitochondrial MTTK c.8344A>G Variant. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2018;6:2324709618802867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Calarco R, Rapaccini G, Miele L. Fat Deposits as Manifestation of Alcohol Use Disorder: Madelung's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:A26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Leung NW, Gaer J, Beggs D, Kark AE, Holloway B, Peters TJ. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois-Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1987;27:601-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |