Published online Sep 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8127

Peer-review started: May 9, 2021

First decision: June 5, 2021

Revised: June 16, 2021

Accepted: July 22, 2021

Article in press: July 22, 2021

Published online: September 26, 2021

Processing time: 129 Days and 19.4 Hours

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses a spectrum of cardiovascular emergencies arising from the obstruction of coronary artery blood flow and acute myocardial ischemia. Recent studies have revealed that thyroid function is closely related to ACS. However, only a few reports of thyrotoxicosis-induced ACS with severe atherosclerosis have been reported.

A 33-year-old man, who had a history of hyperthyroidism without taking any antithyroid drugs and no history of coronary heart disease, experienced neck pain with occasional heart palpitations starting 3 mo prior that were aggravated after an activity. As the symptoms worsened at 21 d prior, he went to a hospital for treatment. The electrocardiogram examination showed a multilead ST segment elevation and pathological Q waves. Based on these findings and his symptoms, the patient was diagnosed with a suspected myocardial infarction and transferred to our hospital on July 2, 2020. He was diagnosed with a rare case of ACS due to coronary artery atherosclerosis in the anterior descending artery complicated by hyperthyroidism. A paclitaxel-coated drug balloon was used for treatment to avoid the use of metal stents, thus reducing the time of antiplatelet therapy and facilitating the continued treatment of hyperthyroidism. The 9-mo follow-up showed favorable results.

This case highlights that atherosclerosis is a cause of ACS that cannot be ignored even in a patient with hyperthyroidism.

Core Tip: We present a case of an acute coronary syndrome due to coronary artery atherosclerosis in the anterior descending artery complicated by hyperthyroidism in a 33-year-old man. Patients with thyrotoxicosis-induced acute coronary syndrome (ACS) are very special, and almost all reported cases have been associated with Graves’ disease. Coronary angiography usually shows zero disease, and coronary artery spasm occupies a large proportion of data, which is contradictory with this case that ACS is accompanied by atherosclerosis. In this case ,we find that intensive drug therapy and implant-free interventional therapy are better options for patients with ACS and hyperthyroidism.

- Citation: Zhu HM, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Yuan H, Li ZX, Long Y. Acute coronary syndrome with severe atherosclerotic and hyperthyroidism: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(27): 8127-8134

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i27/8127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i27.8127

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) encompasses a spectrum of cardiovascular emergencies arising from the obstruction of coronary artery blood flow and acute myocardial ischemia. Patients with ACS frequently have a poor prognosis, and ACS is a major health and economic burden[1,2]. The symptoms of ACS arise from the functional destruction of the circulatory system. However, the pathogenic factors of ACS often arise from systems outside the circulatory system, and diseases related to endocrine system dysfunction, such as diabetes and hyperthyroidism[3], have an indispensable role to play. Such factors increase the difficulty in clinical treatment and improvement of patient prognosis. Therefore, in recent years, coronary heart disease (CHD) secondary to hyperthyroidism has gradually received considerable attention[4]. We describe a rare case of ACS due to coronary artery atherosclerosis in the anterior descending artery complicated by hyperthyroidism in a 33-year-old man. We also present relevant literature and discuss the interaction mechanism between complications and CHD to achieve a suitable treatment plan.

ACS encompasses a spectrum of cardiovascular emergencies arising from the obstruction of coronary artery blood flow and acute myocardial ischemia. Patients with ACS frequently have a poor prognosis, and ACS is a major health and economic burden[1,2]. The symptoms of ACS arise from the functional destruction of the circulatory system. However, the pathogenic factors of ACS often arise from systems outside the circulatory system, and diseases related to endocrine system dysfunction, such as diabetes and hyperthyroidism[3], have an indispensable role to play. Such factors increase the difficulty in clinical treatment and improvement of patient prognosis. Therefore, in recent years, CHD secondary to hyperthyroidism has gradually received considerable attention[4]. We describe a rare case of ACS due to coronary artery atherosclerosis in the anterior descending artery complicated by hyperthyroidism in a 33-year-old man. We also present relevant literature and discuss the interaction mechanism between complications and CHD to achieve a suitable treatment plan.

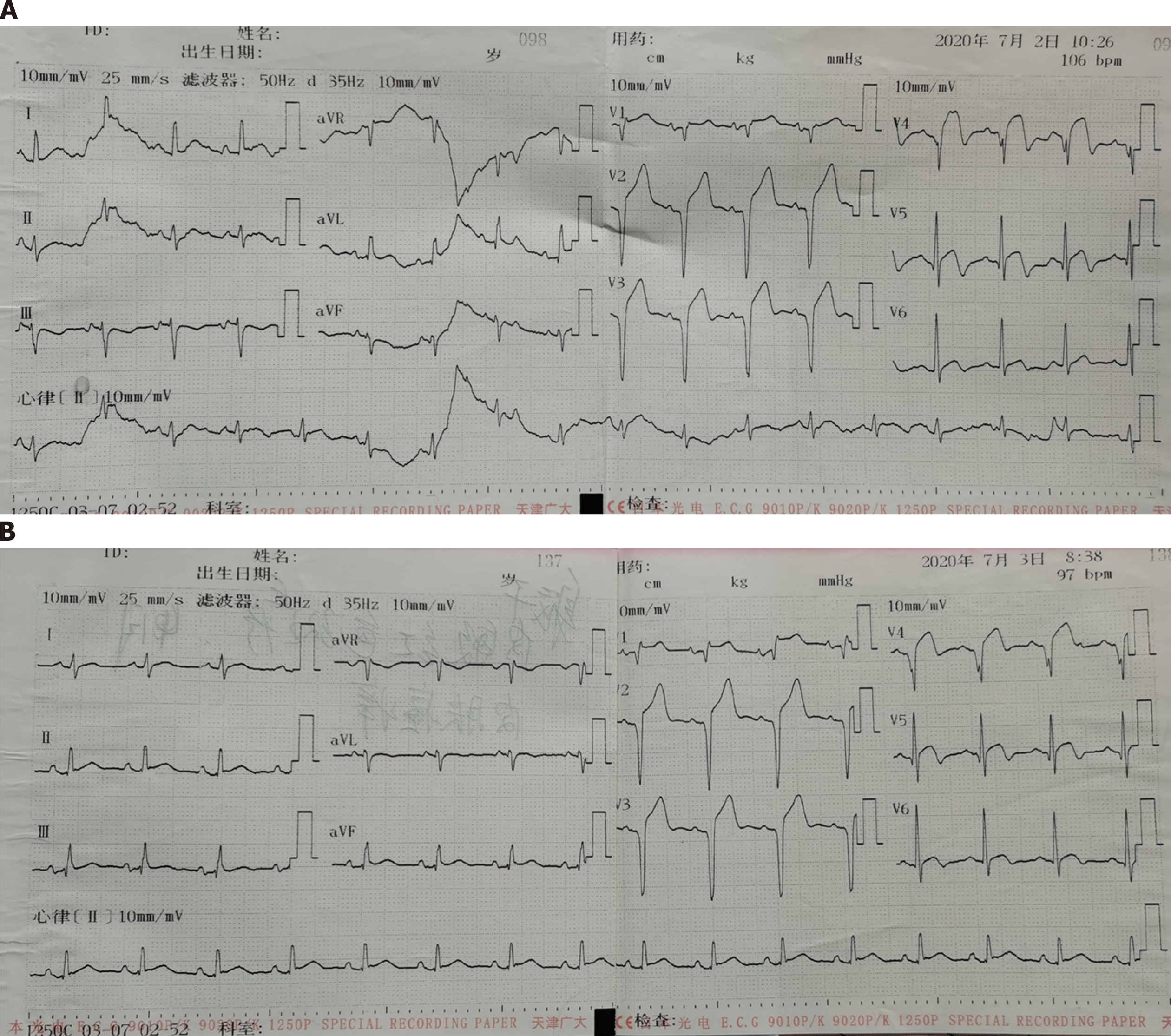

Three months ago, the patient experienced neck pain with occasional heart palpitations that were aggravated after an activity. As the symptoms worsened 21 d prior, he went to a hospital for treatment. The electrocardiogram examination showed a multilead ST segment elevation and pathological Q waves. Based on the findings and his symptoms, the patient was diagnosed with a suspected myocardial infarction.

The patient had a history of hyperthyroidism for 5 mo, without taking any antithyroid drugs. There was no history of CHD.

The patient smoked approximately 12 cigarettes a day for 10 years. He denied a family history of related disease.

After hospitalization, the results of the diagnosis-related examinations were as follows: body temperature, 36.6 ºC; breathing, 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 120/80 mmHg; and heart rate, 110 beats/min. The patient was of sound mind and had a slightly enlarged thyroid with ocular signs. Since the onset of the disease, he has lost 6 kg of weight.

The electrocardiogram results were as follows: sinus rhythm, V1-5 ST segment elevation 0.1-0.4 mv and pathological Q waves (Figure 1).

Although the high-sensitivity troponin T (commonly referred to as TNT-Hs) test result was 29.2 pg/mL on admission and 17.1 pg/mL on day 5 of admission (reference range: 0-0.04 pg/mL), the myocardial enzyme test did not show abnormal results. We also tested the patient’s thyroid function (Table 1 and 2), blood lipids (Table 3), and coagulation function (Table 4). The thyroid function test showed high levels of free triiodothyronine (commonly referred to as FT3), free thyroxine (commonly referred to as FT4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibody (commonly referred to as TRAb), and low level of third-generation thyroid-stimulating hormone (commonly referred to as TSH-3GEN).

| Item | Result | Reference range | Unit |

| FT3 | > 30.00 | 1.71-3.71 | pg/mL |

| FT4 | 3.59 | 0.7-1.48 | ng/dL |

| TSH-3GEN | 0.0017 | 0.4700-4.6400 | IU/mL |

| A-TPO | 2.40 | 0-5.61 | IU/mL |

| A-TG | 0.84 | 0-4.11 | IU/mL |

| TRAb | 12.56 | < 1.75 | IU/L |

| Item | Result | Reference range | Unit |

| FT3 | 11.85 | 1.71-3.71 | pg/mL |

| FT4 | 2.85 | 0.70-1.48 | ng/dL |

| TSH-3GEN | 0.0016 | 0.4700-4.6400 | IU/mL |

| Item | Result | Reference range | Unit |

| CHOL | 3.56 | 2.80-5.17 | mmol/L |

| TG | 1.16 | 0.56-1.70 | mmol/L |

| HDL | 0.81 | 0.96-1.15 | mmol/L |

| LDL | 2.63 | 0-3.10 | mmol/L |

| Item | Result | Reference range | Unit |

| PT-sec | 13.0 | 11-14 | s |

| PT-INR | 1.09 | 0.8-1.2 | N/A |

| APTT | 47.7 | 27-45 | s |

| FIB | 2.83 | 2-4 | g/L |

| TT | 18.6 | 0-20 | s |

| D-Dimer | 0.52 | 0-1 | mg/L |

Cardiac color Doppler ultrasound showed uncoordinated left ventricular wall motion and weakened interventricular septal motion. Thyroid color Doppler ultrasound showed that the bilateral thyroid glands were diffusely enlarged with rich color flow, and bilateral cervical lymph nodes were visible.

The final diagnosis of the presented case was ACS due to coronary artery atherosclerosis in the anterior descending artery complicated by hyperthyroidism.

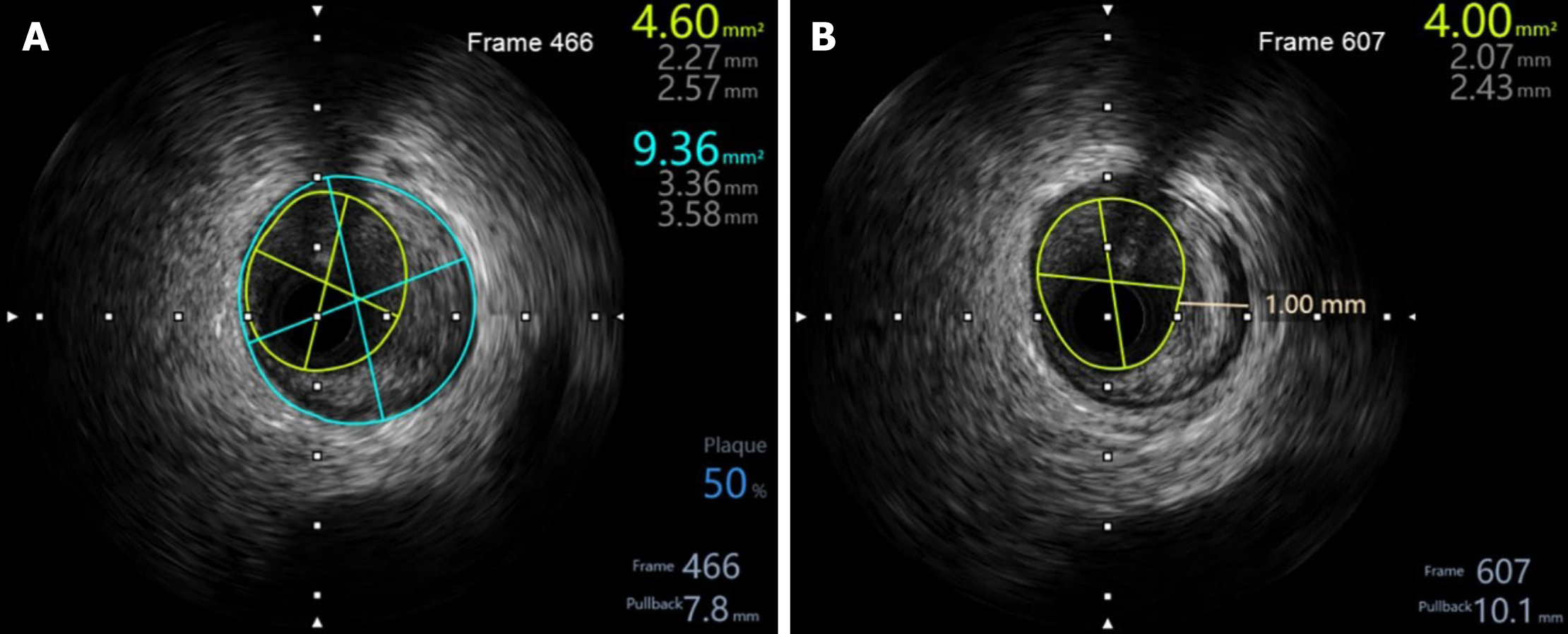

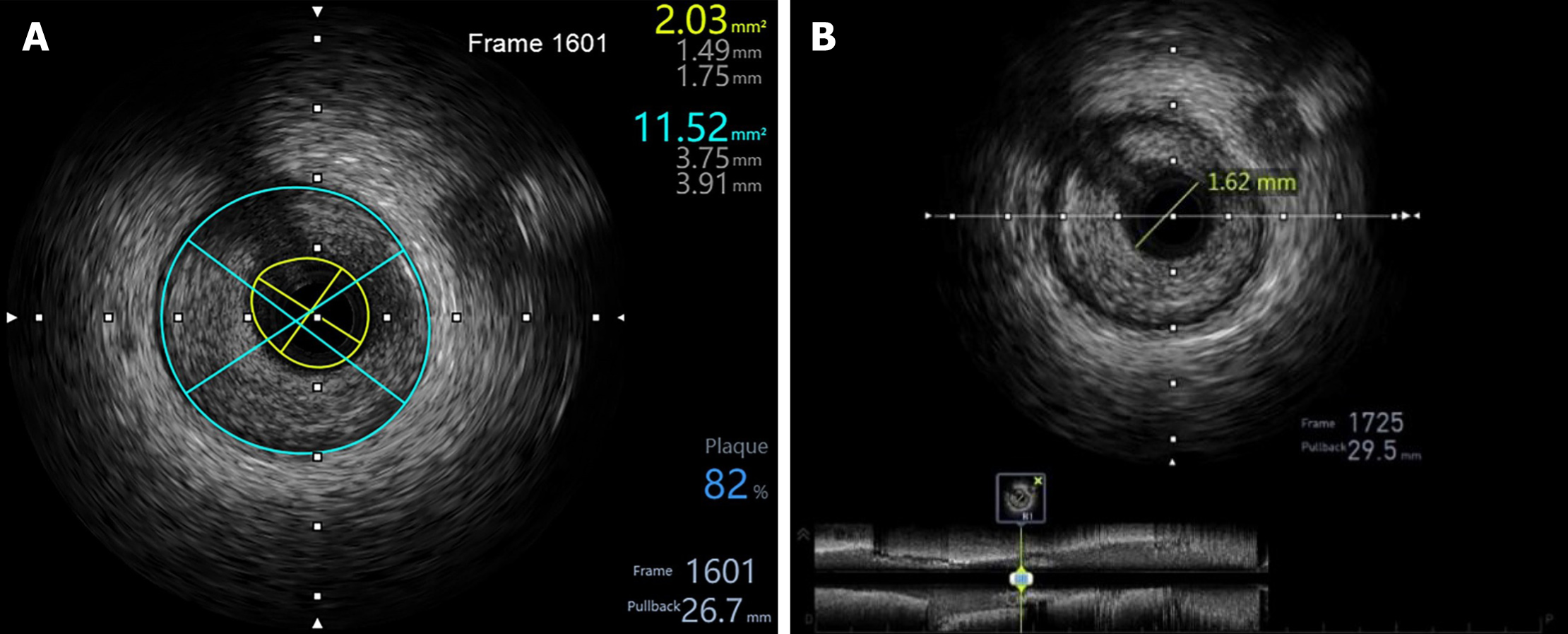

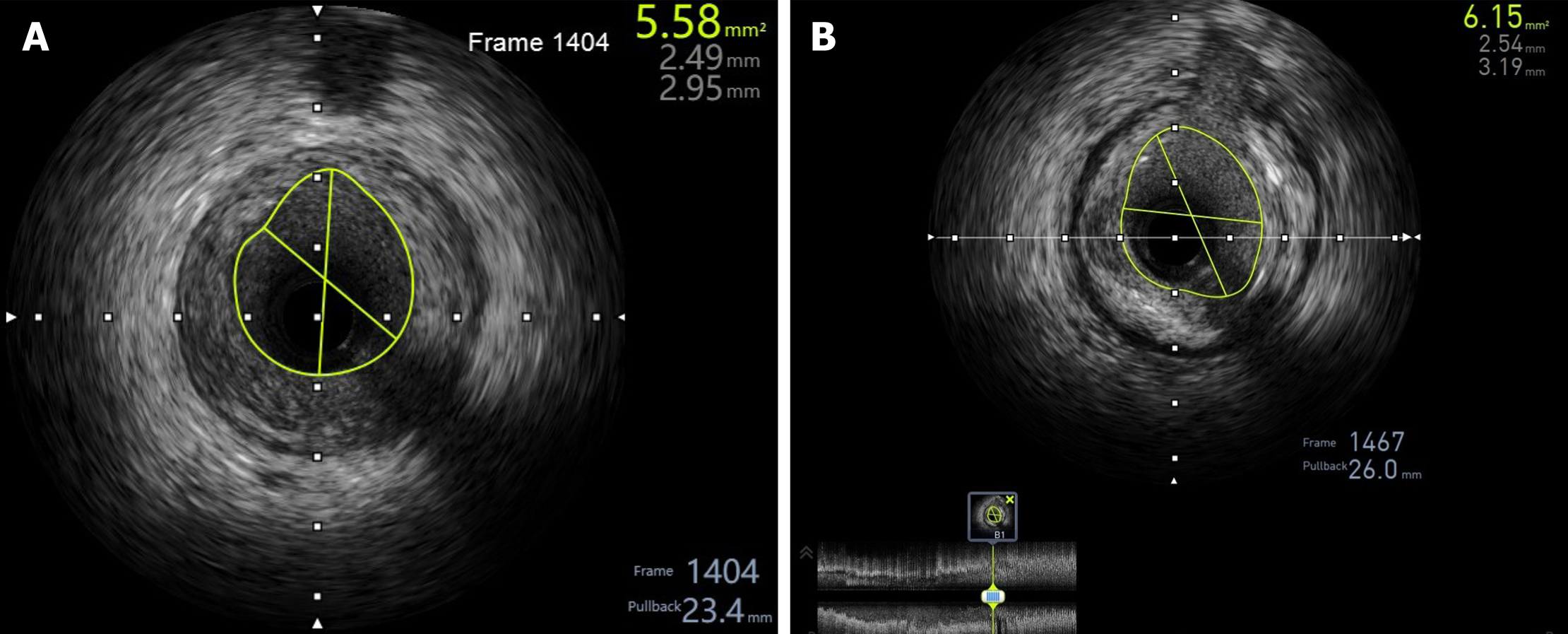

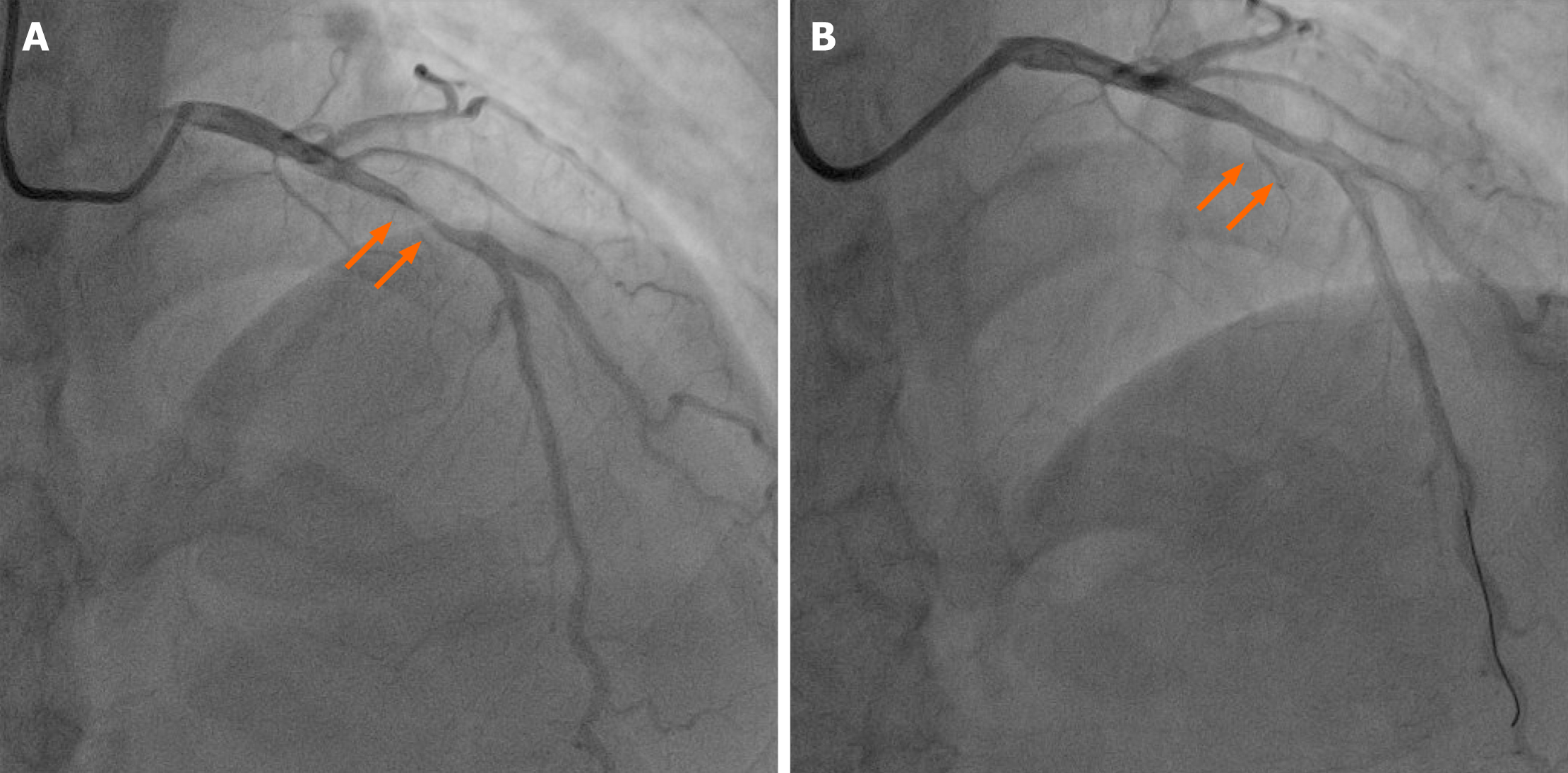

Preoperative intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) examination showed plaque formation in the middle of the anterior descending branch (Figure 2) and severe lesions in the proximal segment. The lesions were rich in lipids and fibrous plaques. The minimum lumen cross-sectional area (referred to as CSA) was 2.03 mm2 (Figure 3), and percutaneous coronary intervention was performed. After the anterior descending branch guide wire was passed, a 2.0 × 20 Abbott Balloon (MINI TREK) 10 atm was administered to predilate the proximal lesion, and a 3.5 × 10 cutting balloon (FlxtomeTM Cutting BalloonTM) was cut twice at 8 atm. Then, a 3.5 × 20 drug-coated balloon (SeQuent; B. Braun Melsungen AG) was expanded at 6 atm for 60 s. Finally, the original narrowest lumen CSA increased to 5.58 mm2 by IVUS examination. There was no local dissection or hematoma formation and coronary angiography showed significant relief of the stenosis (Figure 4 and 5). The patient’s condition improved 4 d after the interventional therapy, and he was discharged. The foregoing oral medication regimen was continued after discharge.

The 9 mo follow-up showed that the patient was in good condition. On March 11, 2021, the cardiac ultrasound showed that left ventricular wall movement was roughly coordinated, and systolic function was normal.

The thyroid hormone has a significant effect on the metabolism of sugar, fat, and protein[5] and acts on all tissue cells. Recent studies have revealed that thyroid hormone widely affects the physiological and pathological processes of the car

Thyroid function is closely related to ACS. Coronary atherosclerosis, one of the most important pathogenic factors leading to ACS, is a long-lasting and continuously evolving disease[11]. Patients with thyrotoxicosis-induced ACS are rare, and almost all reported cases have been associated with Graves’ disease. Coronary angiography usually shows zero disease, and coronary artery spasm occupies a large proportion of data[8,12,13]. However, in this case ACS was accompanied by severe atherosclerosis.

In our patient, the main manifestation was neck pain, which is atypical. The patient was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism because he had a goiter and showed ocular protrusion symptoms. ACS was not diagnosed until the electrocardiogram and TNT-Hs test were completed. Patients with hyperthyroidism often exhibit a high metabolic state[14], and the incidence of diabetes and dyslipidemia in such patients is lower than that in ordinary patients, indicating that the conditions for atherosclerosis are lacking and patients are less likely to have CHD. It is important to understand the factors that caused atherosclerotic plaque in this young male patient with hyperthyroidism. There were several risk factors, including his former work as a courier, a fatty diet, smoking, poor sleep, irregular lifestyle, and stress. During the first half of 2020, the patient had to stay home for several months because of the COVID-19 epidemic, resulting in a lack of physical exercise.

It is possible that severe atherosclerotic plaques already existed in the coronary arteries before the onset of hyperthyroidism, and the environmental risk factors promoted the development of coronary atherosclerosis. It is also possible that newly developed hyperthyroidism induced coronary artery spasm or accelerated the progression of atherosclerosis and subsequent plaque disruption or erosion that led to ACS. Given that IVUS did not accurately reflect the composition of the plaque surface or image the microstructure, optical coherence tomography detection provided a better understanding of the mechanism of ACS onset.

We managed the disease using drug-coated balloon technology. During the treatment, we used the IVUS examination to evaluate the treatment effect of the cutting balloon + drug balloon, which can limit the use of iodine-containing contrast media and reduce the effect of iodine on patients with hyperthyroidism. Patients with hyperthyroidism need to take antithyroid drugs, such as thiourea, for an extended period, which may lead to complications, such as neutropenia. If metal stents were used, the patients may be unable to withstand long-term double antiplatelet therapy because of neutropenia or bleeding. Therefore, we chose the paclitaxel-coated drug balloon as an implant-free interventional therapy to avoid the use of stents, reduce the time of antiplatelet therapy, and facilitate the continued treatment of the patient with subsequent hyperthyroidism.

ACS with hyperthyroidism is easy to miss clinically. In addition to coronary spasms, the mechanism of coronary atherosclerosis is a cause of ACS that cannot be ignored. For young patients, the dangers of smoking, a fatty diet, and sedentary lifestyle should be emphasized. In terms of clinical treatment, intensive drug therapy and implant-free interventional therapy are better options for patients with ACS and hyperthyroidism.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rechciński T S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e78-e140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1953] [Cited by in RCA: 2275] [Article Influence: 175.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4045] [Cited by in RCA: 4400] [Article Influence: 440.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | De Leo S, Lee SY, Braverman LE. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2016;388:906-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 56.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jabbar A, Pingitore A, Pearce SH, Zaman A, Iervasi G, Razvi S. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:39-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Teixeira PFDS, Dos Santos PB, Pazos-Moura CC. The role of thyroid hormone in metabolism and metabolic syndrome. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018820917869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim DH, Choi DH, Kim HW, Choi SW, Kim BB, Chung JW, Koh YY, Chang KS, Hong SP. Prediction of infarct severity from triiodothyronine levels in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29:454-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Viswanathan G, Balasubramaniam K, Hardy R, Marshall S, Zaman A, Razvi S. Blood thrombogenicity is independently associated with serum TSH levels in post-non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1050-E1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Masani ND, Northridge DB, Hall RJ. Severe coronary vasospasm associated with hyperthyroidism causing myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995;74:700-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Coceani M, Iervasi G, Pingitore A, Carpeggiani C, L'Abbate A. Thyroid hormone and coronary artery disease: from clinical correlations to prognostic implications. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:380-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bai MF, Gao CY, Yang CK, Wang XP, Liu J, Qi DT, Zhang Y, Hao PY, Li MW. Effects of thyroid dysfunction on the severity of coronary artery lesions and its prognosis. J Cardiol. 2014;64:496-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boudoulas KD, Triposciadis F, Geleris P, Boudoulas H. Coronary Atherosclerosis: Pathophysiologic Basis for Diagnosis and Management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58:676-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wei JY, Genecin A, Greene HL, Achuff SC. Coronary spasm with ventricular fibrillation during thyrotoxicosis: response to attaining euthyroid state. Am J Cardiol. 1979;43:335-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nannaka VB, Lvovsky D. A rare case of gestational thyrotoxicosis as a cause of acute myocardial infarction. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Singh I, Hershman JM. Pathogenesis of Hyperthyroidism. Compr Physiol. 2016;7:67-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |