Published online Sep 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7886

Peer-review started: April 19, 2021

First decision: May 24, 2021

Revised: May 27, 2021

Accepted: July 21, 2021

Article in press: July 21, 2021

Published online: September 16, 2021

Processing time: 143 Days and 16.5 Hours

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma (IBC) is a rare benign hepatic tumor that is often misdiagnosed as other hepatic cystic diseases. Therefore, imaging examinations are required for preoperative diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has gained increasing popularity as an emerging imaging modality and it is considered the primary method for screening IBC because of its specificity of performance. We describe an unusual case of monolocular IBC and emphasize the performance of CEUS.

A 45-year-old man complained of epigastric pain lasting 1 wk. He had no medical history of hepatitis, liver cirrhosis or parasitization. Physical examination revealed a mass of approximately 6 cm in size in the upper abdomen below the subxiphoid process. Tumor marker tests found elevated CA19-9 levels (119.3 U/mL), but other laboratory tests were unremarkable. Ultrasound and computerized tomography revealed a round thick-walled mass measuring 83 mm × 68 mm located in the left lateral lobe of the liver that lacked internal septations and manifested as a monolocular cystic structure. CEUS demonstrated that in the arterial phase, the anechoic area manifested as a peripheral ring with homogeneous enhancement. The central part presented with no enhancement. During the portal phase, the enhanced portion began to subside but was still above the surrounding liver tissue. The patient underwent left partial liver lobectomy and recovered well without tumor recurrence or metastasis. Eventually, the results of pathological examination confirmed IBC.

A few IBC cases present with monolocular characteristics, and the lack of intracystic septa in imaging performance cannot exclude IBC.

Core Tip: We report the case of a 45-year-old man with intrahepatic biliary cysta

- Citation: Che CH, Zhao ZH, Song HM, Zheng YY. Rare monolocular intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(26): 7886-7892

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i26/7886.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7886

Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma (IBC) is a rare, benign hepatic tumor that is often misdiagnosed as other hepatic cystic diseases in view of its atypical clinical manifestations[1]. Therefore, imaging examinations are needed for the preoperative diagnosis of the disease[2]. Because of its convenience and precision and the absence of radiation, contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) has gained increasing popularity as an emerging imaging modality. CEUS performs well for the diagnosis of IBC, is highly specific, and is considered a primary method for tumor screening[3]. Herein, we describe a unique case of monolocular IBC, which rarely lacks internal septations, emphasize the performance of CEUS, and review the literature.

A 45-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of epigastric pain lasting 1 wk.

The patient felt persistent upper abdominal pain in the previous 1 wk without obvious inducement, nausea or vomiting, or intolerance of cold or fever. Abdominal ultrasound at a local hospital demonstrated a honeycomb structure in the left lateral lobe of liver. He then presented at our hospital for further treatment.

He was in good health and did not have a medical history of hepatitis, liver cirrhosis or parasitization.

The patient had a 20-year history of smoking and alcohol abuse but did not have other risk factors. His parents and family members were healthy.

The patient's skin and sclera were not yellow and the abdomen did not appear floppy. A mass approximately 6 cm in size was palpable below the subxiphoid process in the upper abdomen, which was soft and had a fair range of motion, clear boundaries and local tenderness. There was no significant tenderness or rebound tenderness in the remaining abdomen. The liver and spleen were not palpable under the ribs, and normal bowel sounds were observed. Shifting dullness was noted, and Murphy’s sign was negative.

Laboratory findings included a decreased erythrocyte count (3.46 × 1012/L, normal range: 4.3-5.8 × 1012/L), decreased hemoglobin count (122 g/L, normal range: 130-175 g/L), decreased hematocrit (0.37%, normal range: 40%-50%), elevated mean corpuscular volume (MCV, 105.2 fl, normal range: 82-100 fl) and elevated mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH, 35.1 pg, normal range: 27-34 pg). The leucocyte and platelet counts were normal. Liver function and renal function tests revealed no abnormalities. Tumor marker tests showed strongly elevated carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 (119.3 U/mL; normal range: 0-37.00 U/mL) and elevated CA50 (27.34 IU/mL; normal range: 0-25.00 IU/mL), but alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA-125, CA-242, and CA72-4 were within their normal ranges.

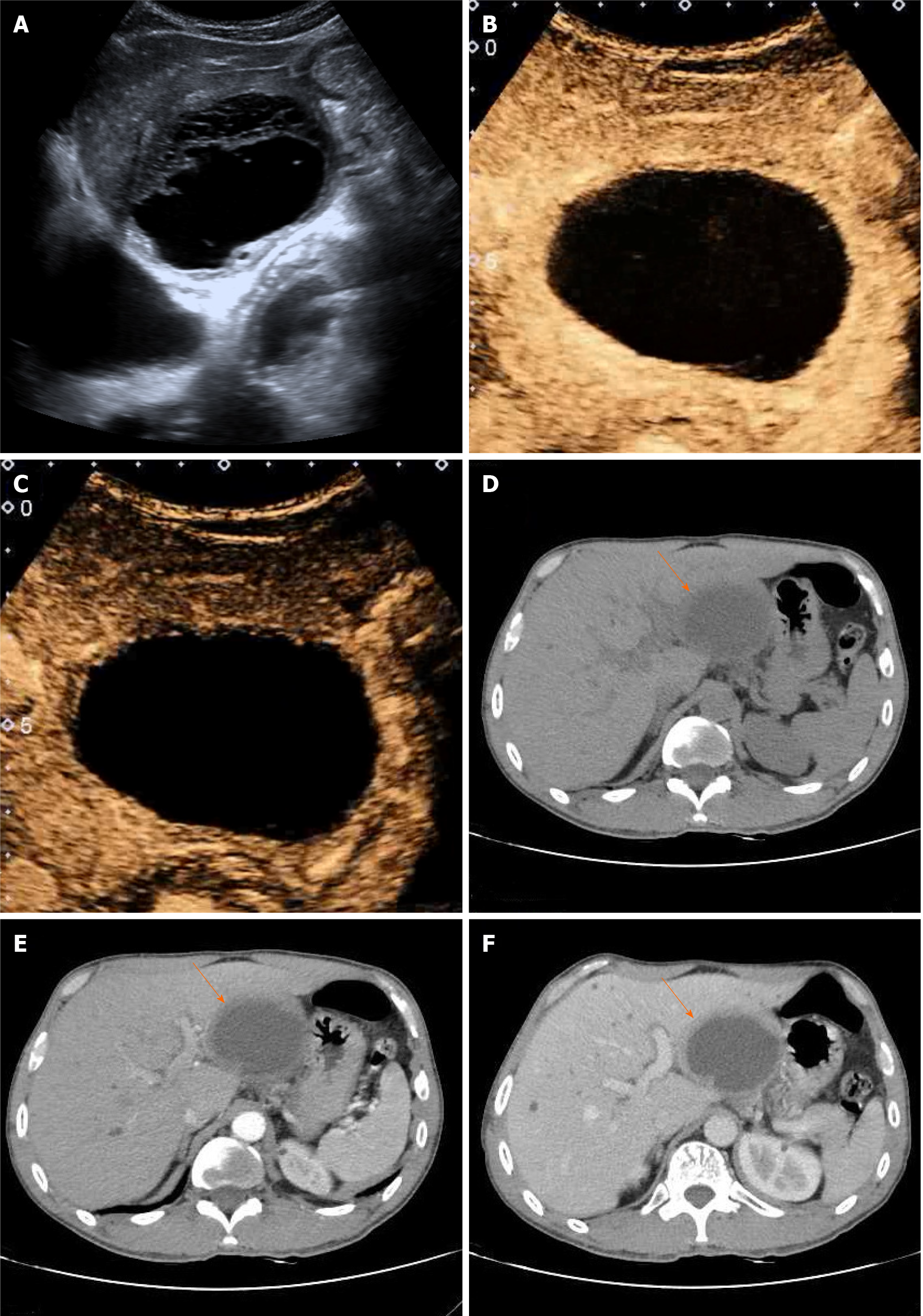

Sonographically, a round anechoic area measuring 83 mm × 68 mm was located in the left lateral lobe of the liver. The wall was homogeneously thickened, with clear borders, a regular shape, and septations (Figure 1A). Color Doppler ultrasound revealed no blood flow signal inside the thick-walled anechoic area. CEUS was performed after a 2 mL injection of the ultrasound contrast agent SonoVue (known as Lumason in the United States; Bracco, Milan, Italy) followed by a bolus injection of 5 mL of a 0.9% sodium chloride solution. At 14 s of the arterial phase, the intrahepatic thick-walled anechoic area manifested peripheral ring homogeneous enhancement, while the central part presented no enhancement with no enhancement of separation (Figure 1B). The enhanced portion began to subside slowly at 50 s during the portal phase, but the cyst wall was still above the surrounding liver tissue (Figure 1C).

Computerized tomography (CT) revealed that the size and shape of the liver and spleen were normal, with an intact capsule. A thick-walled, low-density, and clear-boundary shadow measuring 83 mm × 68 mm in size, and with a CT value of approximately 23 HU was observed in the left lateral lobe of the liver. The cyst fluid density was uniform, with a CT value of approximately 17 HU. In addition, intracapsular septa were absent (Figure 1D). Enhanced CT revealed wall enhancement in the arterial phase with a CT value of approximately 41 HU (Figure 1E) and homogeneous enhancement in the portal phase (Figure 1F). There were multiple small cystic lesions without enhancement. The density of the remaining parenchyma was uniform. The biliary tract was not significantly dilated, and the gallbladder and pancreas showed no abnormalities.

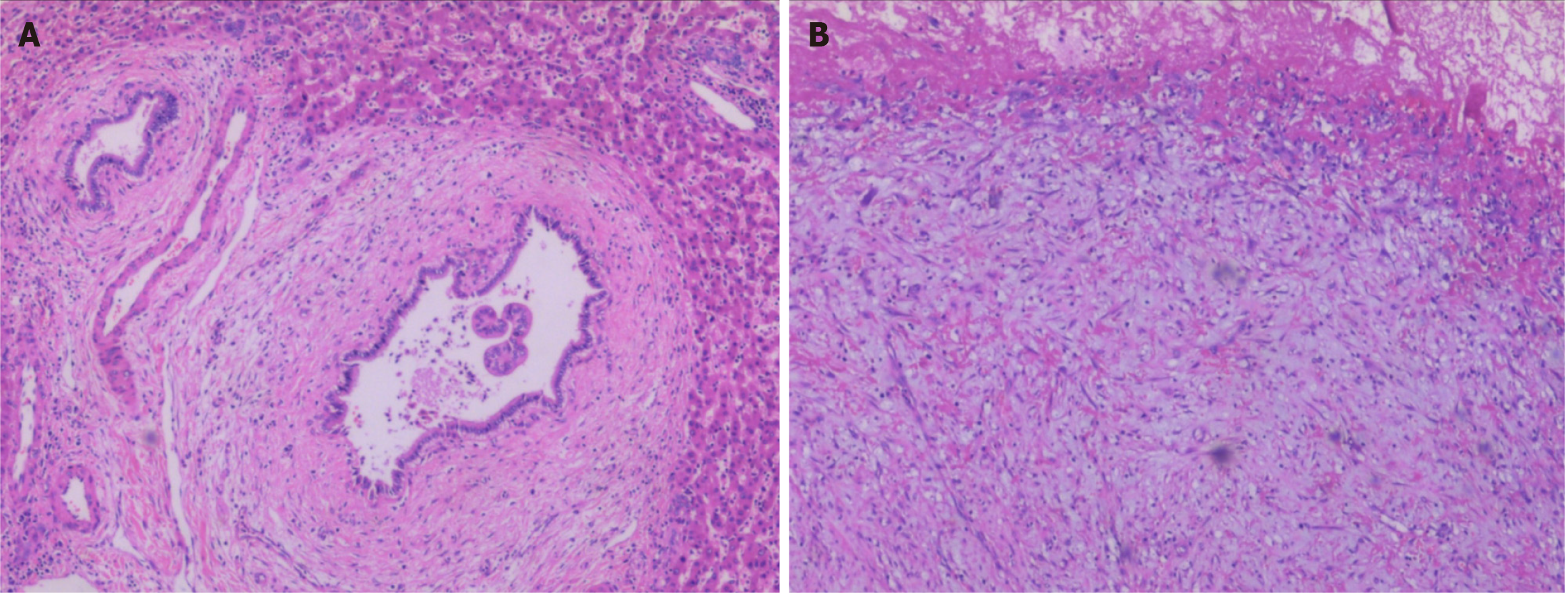

Pathologically, the tumor wall was composed of a single layer of cuboidal and columnar epithelium cells (Figure 2A), with fibrinoid necrosis observed in the cyst. Fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and interstitial mucinous degeneration were observed in the peripheral stroma (Figure 2B). Some of the biliary epithelium showed evidence of active proliferation. Immunohistochemically, the tumor was AFP (+), CD34 (+) in vessels, CK19 (+), hepatocyte (+), and < 10% Ki-67 (+). The patient was finally diagnosed with IBC.

The patient underwent a left partial liver lobectomy. The resected left lateral lobe specimen included a monolocular cystic lesion of approximately 8 cm that was soft, well-defined, and surrounded by a white capsular wall. Yellowish, gelatinous fluid filled the mass.

After re-examination, all indicators were normal, the patient recovered well after treatment, was without obvious discomfort, and was discharged 1 wk later. The most recent CT, performed after 2 years of follow-up, revealed no tumor recurrence or metastasis.

IBC, which originates from the biliary epithelial cells and usually appears within the intrahepatic bile duct (80%-90%), rarely in the extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder, and is an uncommon benign hepatic cystic tumor that accounts for less than 5% of all hepatic solitary cysts. It has been reported that the disease can occur at any age, especially in middle-aged women, and at a median age of 50 years. Statistically, the tumor size typically ranges from 1.5 cm to 35 cm[2,4].

At present, the etiology of IBC is unclear and possibly related to residual foregut or gonadal epithelial tissues in the liver resulting from abnormal embryonic development[5]. The gross anatomy of IBC manifests as a single structure with an intact capsule and smooth cyst wall. The majority present with multiple septations within the tumor. In the current case, the tumor was described as monolocular because of a lack of septation. The capsule is filled with radiolucent or gelatinous yellow cystic fluid, and intracapsular nodules or papillary structures can sometimes exist[6]. Histologically, the cyst wall is composed of a single layer of cuboidal or columnar epithelium cells with mesenchymal stroma presenting as ovarian-like, fibroid, hyaline, myxoid, or other tissue. In addition, very few IBCs lack stroma[1,7].

IBC progresses slowly, with a long disease duration. The majority of patients are asymptomatic, but others experience nonspecific manifestations such as abdominal pain, abdominal distension, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice[8]. On physical examination, abdominal masses and local tenderness are observed. Laboratory findings of the patients are usually normal, but sometimes mildly elevated serum liver enzyme and bilirubin levels are noted. Serum tumor markers, including AFP, CA19-9, CA-125 and CEA, are usually within the normal range. However, the serum level of CA19-9 was highly elevated in this case. We believe that an increased serum level of CA19-9 can be helpful for the preoperative diagnosis of IBC with the premise of excluding malignant pancreatic cancer and significant biliary obstruction, in which CA19-9 is elevated[9,10].

Imaging examination is one of the main diagnostic methods. Ultrasound is the most widely used, but CEUS has been increasingly used in clinical practice in recent years. US reveals that IBC often presents as a round or lobulated area with a thick and homogeneous cystic wall showing hyperechogenicity, a smooth inner margin, and a clear outer margin. Multiple septations in anechoic areas are characteristic of IBC[7]. CEUS reveals homogeneous and continuous high enhancement of the cyst wall and septa in the arterial phase that is significantly higher than in the surrounding normal liver tissue because of abundant blood perfusion in the cyst wall and septa. Solid tissues such as nodules with a rich blood flow are sometimes observed on the cyst wall or septa. They are small and have a regular shape and homogeneous enhancement. The central anechoic area shows no enhancement because the sac is filled with serous or mucinous capsule fluid without blood perfusion. In the portal phase, solid structures such as the cyst walls, septa and nodules show enhancement that gradually decreases until reaching the surrounding normal liver tissue.

Although it is difficult to distinguish IBC from some hepatic cystic diseases in terms of clinical manifestations, CEUS can be used as the mainstay of differential diagnosis because of the distinctive characteristics of IBC on imaging. We have summarized the differences between IBC and other diseases based on ultrasound and CEUS characteristics: (1) In liver abscess, US shows single or multiple anechoic areas. The abscess wall is hyperechogenic with an uneven wall thickness, a rough inner margin, and an unclear outer margin. CEUS demonstrates significant enhancement of the abscess wall and internal septa but no enhancement of liquefied necrotic portions, which present as a typical honeycomb; (2) In hepatic echinococcosis, US reveals a round anechoic area with floating small light spots. The capsule wall presenting as a double-layered structure that is smooth and intact, with occasional collapse and dissection of the internal wall. Simultaneously, strongly echoic areas caused by calcification can be observed in the periphery of the capsule wall. CEUS shows no significant enhancement; (3) In Caroli’s disease, color Doppler ultrasound reveals a circumscribed dilated anechoic area in the common hepatic duct or intrahepatic bile duct, which is oval or triangular in shape and without obvious enhancement; (4) In biliary cystadenocarcinoma US reveals that the cyst wall is rough and has an uneven thickness, and is sometimes accompanied by strongly echoic areas of calcification. CEUS reveals numerous large mural nodules with enhanced heterogeneity and an irregular shape; and (5) In primary liver cancer, US reveals single or multiple masses presenting complex echoes in the liver parenchyma, with annular hypoechoic vocal cords around the tumor. On CEUS, the tumor presents overall homogeneous hyperenhancement earlier than the liver parenchyma in the arterial phase and hypoenhancement in the portal phase.

As an imaging examination that is complementary to US, CT can more graphically illustrate cystic lesions. Enhanced CT reveals a uniform and continuous enhancement of solid structures such as cyst walls, septa, and cyst wall nodules but no enhancement of the contents of the cyst[11]. Magnetic resonance imaging facilitates the assessment of cystic fluid properties, and cystic fluid in IBC generally presents hypointensity on T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and hyperintensity on T2WI. The signal intensity of T1WI may be elevated with increasing cyst fluid protein concentrations, with lower intensity for serous fluid and bile and higher intensity for mucinous components[12].

It is worth noting that in this case, CEUS, scan and enhanced CT showed no visible septation within the tumor; only a small septation was observed on ordinary ultrasound because the internal septa were scant and lacked blood perfusion. Therefore, it has been confirmed that a small number of IBCs lack intracapsular septa, presenting as a round or irregularly shaped monolocular cystic structure. The absence of intracapsular septation on US or CT cannot be used as an imaging basis to exclude IBC.

Surgical resection is the preferred method of treatment for IBC. If resection of the lesion is not complete, postoperative recurrence will generally occur and may even be cancerous. The recurrence rate is 90% and 30% are malignant[13]. Therefore, early radical tumor resection is vital for surgical efficacy and prognosis. The scope of radical surgery includes the tumor and a small amount of liver tissue around it. If necessary, it is feasible to expand the scope of surgery or even perform liver transplantation. Intraoperative frozen sections can help to determine whether the tumor is benign or malignant and whether the scope of resection is adequate. It is currently believed that conservative treatment of simple liver cysts, such as aspiration, drainage, and marsupialization, are not recommended due to the poor patient prognosis[14]. IBC patients usually recover well, with a low recurrence rate of 5%-10%. Sang et al[15] reported that the 10-year survival rate of IBC patients exceeded 90%.

This article reports a rare case of monolocular IBC with a focus on its imaging features, especially on CEUS, which is helpful for disease diagnosis. However, because a minority of IBCs manifest as monolocular cystic tumors, the lack of intracystic septa cannot be regarded as imaging evidence to exclude IBC.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Society of Ultrasonography; Interventional Medicine Branch of Zhejiang Medical Association; Key Discipline of Ultrasound Medicine in Shaoxing City.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Machado P S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Tholomier C, Wang Y, Aleynikova O, Vanounou T, Pelletier JS. Biliary mucinous cystic neoplasm mimicking a hydatid cyst: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kazama S, Hiramatsu T, Kuriyama S, Kuriki K, Kobayashi R, Takabayashi N, Furukawa K, Kosukegawa M, Nakajima H, Hara K. Giant intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma in a male: a case report, immunohistopathological analysis, and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1384-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pang EHT, Chan A, Ho SG, Harris AC. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound of the Liver: Optimizing Technique and Clinical Applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210:320-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu RM, Li XR, Liu LH, Zheng WQ, Zhou H, Wang XC. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:5670-5677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Treska V, Ferda J, Daum O, Liska V, Skalicky T, Bruha J. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma-diagnosis and treatment options. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2016;27:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang C, Miao R, Liu H, Du X, Liu L, Lu X, Zhao H. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: an experience of 30 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:426-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bardin RL, Trupiano JK, Howerton RM, Geisinger KR. Oncocytic biliary cystadenocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:e25-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, Bauer TW, Pawlik TM. Cystic neoplasms of the liver: biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, Rauws EA, van Delden OM, Gouma DJ, van-Gulik TM. Obstructive jaundice due to hepatobiliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5735-5738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Steinberg W. The clinical utility of the CA 19-9 tumor-associated antigen. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:350-355. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Xu HX, Lu MD, Liu LN, Zhang YF, Guo LH, Liu C, Wang S. Imaging features of intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma on B-mode and contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:E241-E249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ratti F, Ferla F, Paganelli M, Cipriani F, Aldrighetti L, Ferla G. Biliary cystadenoma: short- and long-term outcome after radical hepatic resection. Updates Surg. 2012;64:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Teoh AY, Ng SS, Lee KF, Lai PB. Biliary cystadenoma and other complicated cystic lesions of the liver: diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. World J Surg. 2006;30:1560-1566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thomas KT, Welch D, Trueblood A, Sulur P, Wise P, Gorden DL, Chari RS, Wright JK Jr, Washington K, Pinson CW. Effective treatment of biliary cystadenoma. Ann Surg. 2005;241:769-73; discussion 773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sang X, Sun Y, Mao Y, Yang Z, Lu X, Yang H, Xu H, Zhong S, Huang J. Hepatobiliary cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas: a report of 33 cases. Liver Int. 2011;31:1337-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |