Published online Sep 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7863

Peer-review started: March 26, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 19, 2021

Accepted: August 2, 2021

Article in press: August 2, 2021

Published online: September 16, 2021

Processing time: 167 Days and 23.8 Hours

Due to the increasing number of diagnosed nonpalpable breast cancer cases, wire localization has been commonly performed for surgical guidance to remove nonpalpable breast lesions. This report presents a rare case of localized wire migration to a subcutaneous lesion of the upper back in a breast cancer patient undergoing breast-conserving surgery.

A 48-year-old female was scheduled for breast-conserving surgery for left breast cancer. Ultrasonography guided wire localization was performed intraoperatively by surgeon to localize the nonpalpable breast cancer. After axilla sentinel lymph node biopsy, we realized that the wire was not visualized. The wire was not found in the operation field, including the breast and axilla. Breast-conserving surgery was performed after wire re-localization. Intraoperative chest posteroanterior view revealed that the wire was located on the level of midaxillary line. Two days after the operation, a serial simple X-ray revealed that the wire was located on the subcutaneous lesion of the back. The wire tip was palpable under the skin of the upper back, and the wire was removed under local anesthesia.

Hooked wire misplacement can lead to fatal complications. Surgeons must consider the possibility of wire migration during breast cancer surgery.

Core Tip: Wire localization is commonly used method to localize nonpalpable breast cancer. Wire migration is infrequent complication, but the loss of a hooked wire can lead to fatal complications. Surgeons must consider the possibility of wire migration during breast cancer surgery, and the device must be found and removed.

- Citation: Choi YJ. Migration of the localization wire to the back in patient with nonpalpable breast carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(26): 7863-7869

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i26/7863.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7863

Various methods, including wire localization, radio-guided occult lesion localization, radioactive seed localization, and intraoperative ultrasonography, have been used to localize tumor, identify the appropriate margin, and increase accuracy in breast conserving surgery (BCS) for nonpalpable breast cancer[1]. Preoperative mammo

In this study, we present a rare case wherein a localized hooked wire migrated to the subcutaneous lesion of the upper back and was removed through the skin in a breast cancer patient undergoing breast-conserving surgery.

A 48-year-old woman visited the breast clinic of Chungbuk National University Hospital for an ultrasonographic abnormality detected on a routine check-up. She didn’t complain any other breast problem including pain and lump.

The patient visited local breast clinic for routine check-up. She underwent mammography and breast ultrasonography and breast ultrasound suggested the left breast mass as possible malignant breast tumors (BI-RADS 4B). The patient referred to our hospital for accurate diagnosis and surgical treatment. She underwent breast ultrasonography two years ago and at that time, there was no evidence of abmo

She was in a premenopausal status. She has two children and she breastfed both of her children for more than one year. She was of normal weight, with a body mass index of 21.3 kg/m2. She has never had hormone therapy before and she didn't drink or smoke at all. She has been healthy and has never been diagnosed with diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, or tuberculosis.

Her older sister was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 46. Tests for mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes showed no abnormalities. She denied any other significant medical history of breast cancer and breast premalignant lesion.

On physical exam, there were no definite palpable mass and skin change in the breast and axilla. There were no evidence of nipple discharge and nipple retraction.

Laboratory examinations including the serum tumor markers were all within normal range.

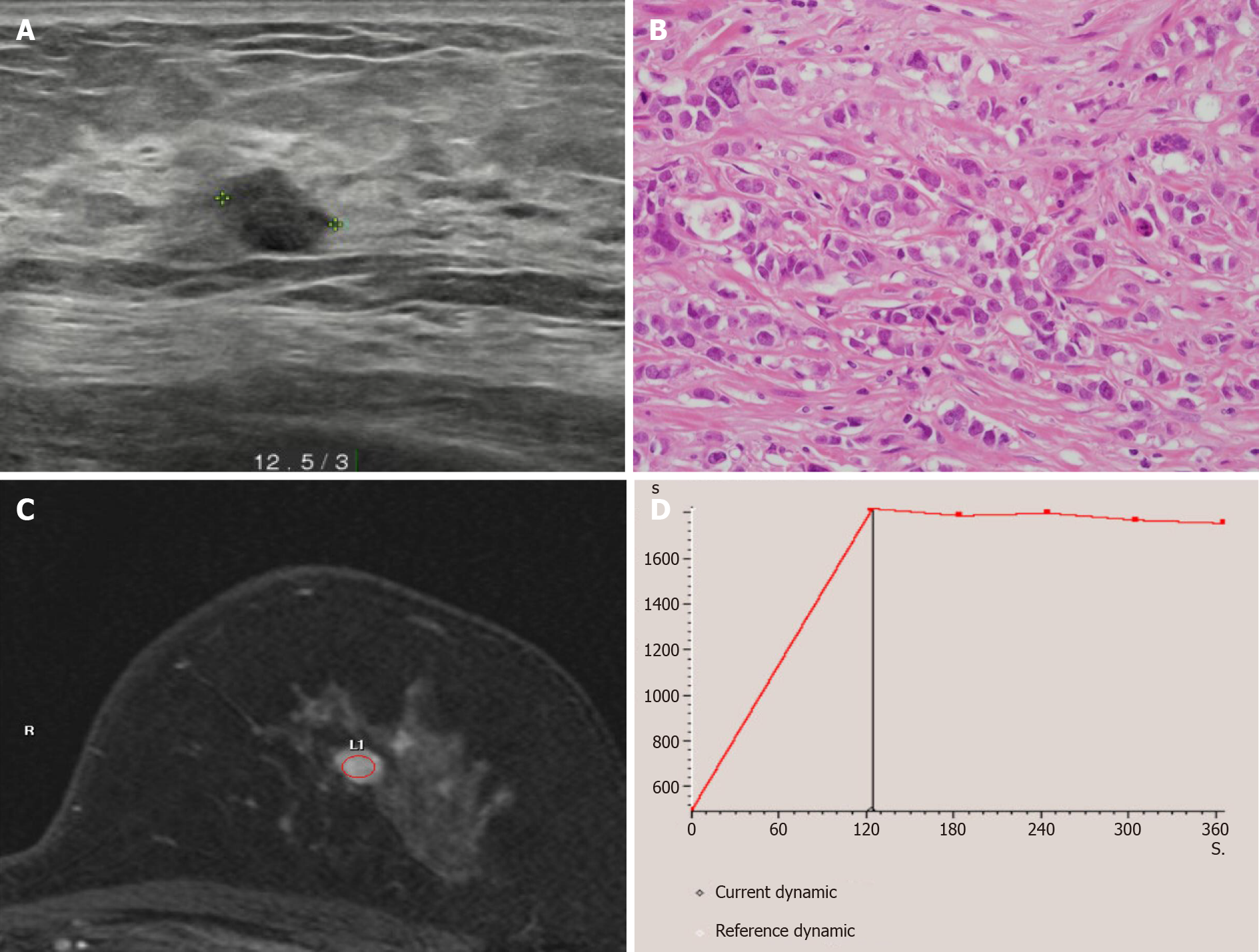

Mammography showed a dense breast, and breast ultrasonography showed a 0.8 cm × 0.7 cm irregular hypoechoic mass, located on the left, 12:30 o’clock position, and 3 cm away from the left nipple. The patient was diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma following an ultrasound guided (USG) core needle biopsy. Breast magnetic resonance imaging showed a solitary enhancing mass with a type II dynamic curve (Figure 1). The chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) scans and bone scan showed no evidence of distant metastasis. She was scheduled for breast-conserving surgery with a sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy.

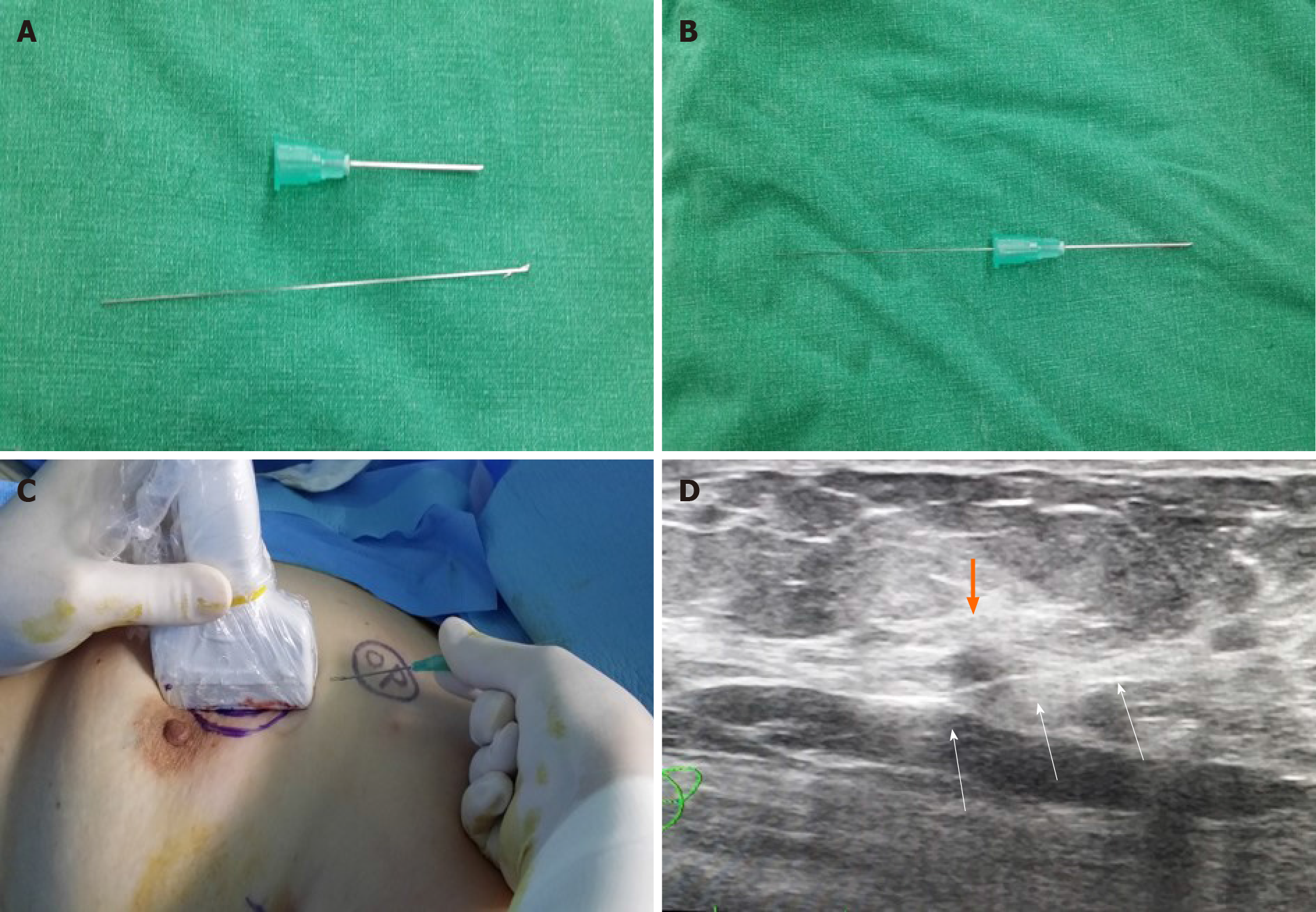

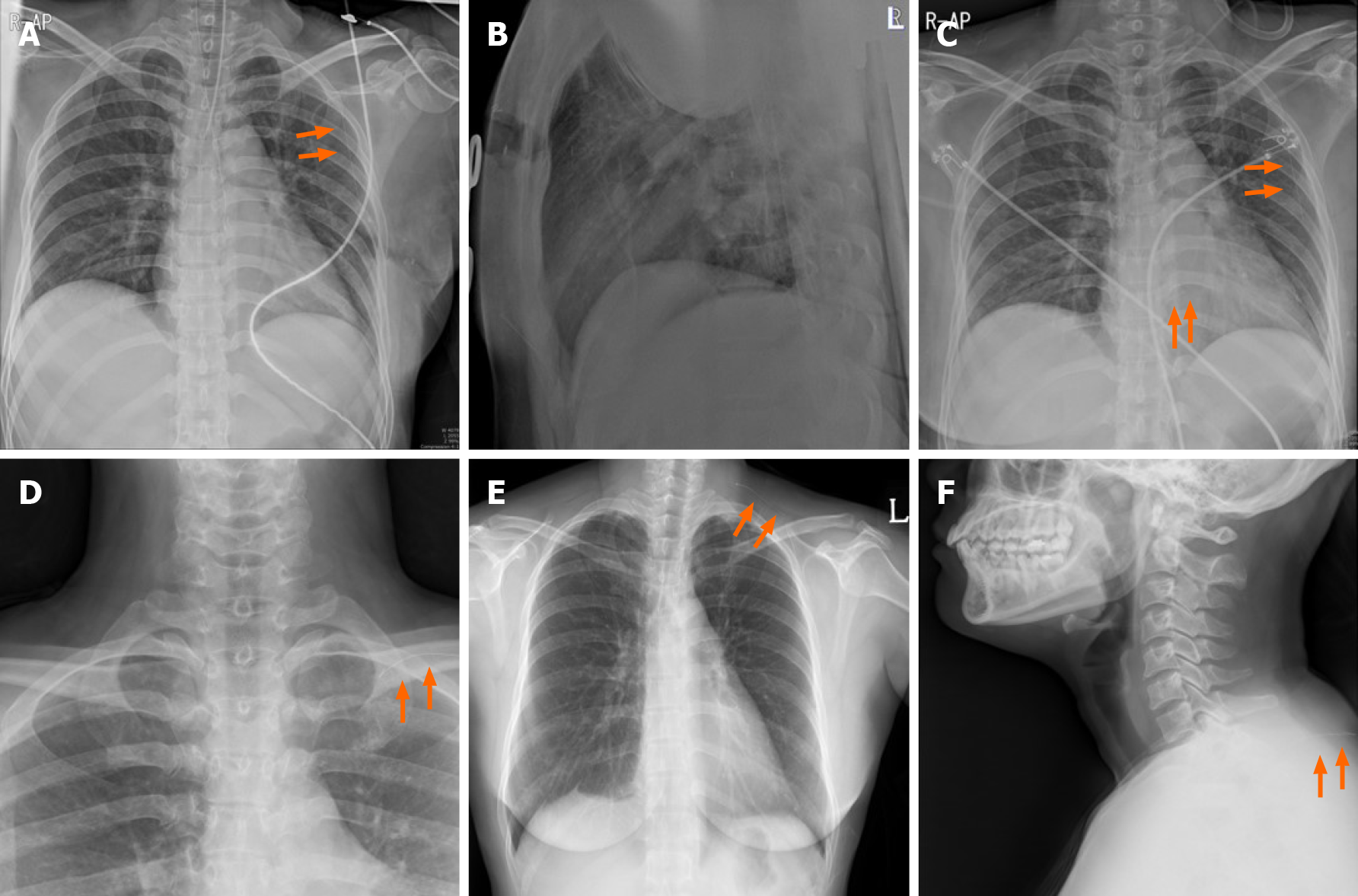

The wound was disinfected and draped following general anesthesia. USG guided wire localization was then performed intraoperatively to localize the nonpalpable breast cancer by surgeon. The breast lesion localization wire consisted of a 23-gauze needle for localization, through which a 25-gauze 10 cm monofilament wire with a distal hook was inserted and left in the breast as the needle was totally withdrawn (Figure 2). SLN biopsy was performed. Two SLNs were dissected from the left axilla and sent for frozen pathology. After SLN biopsy, we realized that the wire was not visualized. The wire was not located in the operation field, including the breast and axilla. Breast-conserving surgery was performed after wire re-localization. Despite the operation field search, the missed wire was still not found. Intraoperative portable chest posteroanterior (PA) X-ray revealed the wire located along the midaxillary line. However, it was not detected on lateral film. The pectoralis fascia layer was further dissected into upper and lower directions under the assumption that the wire was in the breast. The localization wire was not found in the breast and axilla. Frozen biopsy revealed no metastasis in the SLN, and there was no evidence of malignancy on the cavitary resection margin. The patient was subsequently extubated, and a recovery room portable chest PA X-ray confirmed its location along the midaxillary line. The patient did not exhibit pneumothorax. While recovering, the patient had stable vital signs and was asymptomatic. One day after the operation, a neck X-ray revealed that the wire was located at the clavicular level. Two days after the operation, a serial simple X-ray revealed that the wire was located on the subcutaneous lesion of the back (Figure 3). The patient complained of left upper back pain. The tip of the distal end of the wire (the hook) was palpable under the skin of the upper back. The wire was removed under local anesthesia without complications.

The tumor was diagnosed as invasive ductal carcinoma with intermediate histologic grade, measuring 0.8 cm × 0.7 cm in diameter. The two SLNs showed no evidence of metastasis. The breast carcinoma was immunohistochemically positive for estrogen receptor (3+, 90%) and progesterone receptor (2+, 70%) and was negative for C-erb-B2. The Ki-67 proliferation index was 10%. The tumor was diagnosed as pathologic stage I (pT1bN0M0) breast cancer according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.

Three days after the operation, the patient was discharged without complications. Adjuvant endocrine therapy with tamoxifen 20 mg/d was initiated, and she underwent adjuvant radiation therapy for her left breast.

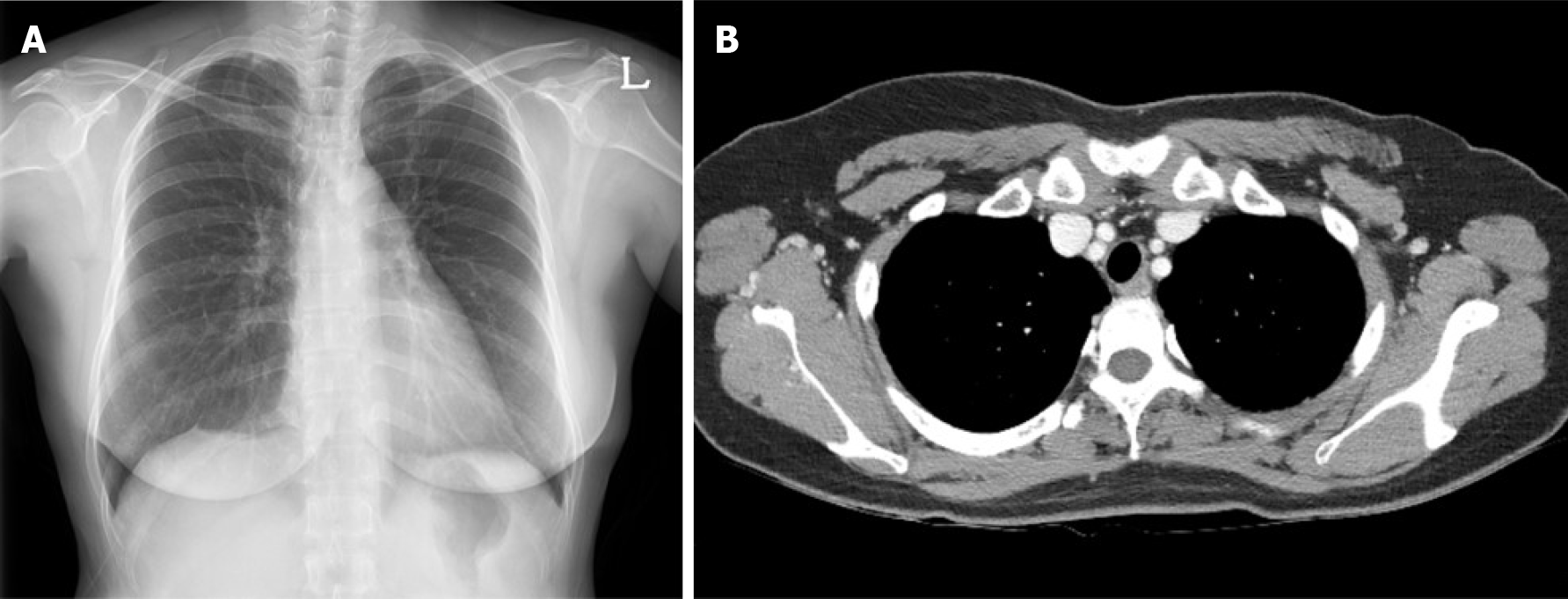

Three months after surgery, a chest PA X-ray and chest CT revealed no evidence of remnant wire or pneumothorax and other abnormalities (Figure 4). Currently, the patient is undergoing endocrine therapy with tamoxifen, and no evidence of metastasis has been observed 48 mo after surgery.

Due to the increase in diagnosed nonpalpable breast cancer cases, wire localization under mammography and ultrasonography has been performed more frequently to localize tumors, spare noninvolved breast tissues, and increase the accuracy of breast-conserving surgery. Although this procedure is generally tolerable, its complications, including bleeding, pain, premature wire removal, and vasovagal reactions, are relatively common. Other rare complications include wire fragmentation, wire migration, pneumothorax, pleural migration, and tumor seeding[3-7].

Wire migration is a rare complication. Some reports have documented the wire migrating to the lung, pleura, heart, diaphragm, and abdomen. These were removed by vascular intervention, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to open thoracotomy, and laparotomy[5-8]. Migrating or missing wires were identified during the procedure or surgery, but some were incidentally discovered months or years later. In such cases, the patients were asymptomatic during the procedure and surgery. However, missing wires that are left unfound may later present as major vital organ abnormalities, leading to potentially fatal problems[5-8].

Retention of wire fragments after localization may have no clinical significance, and the wires do not appear to move within the breast tissue. No harm appears to be caused by small wire fragments left in the breast and asymptomatic wire fragments may be left without adverse effects[9,10]. Considering the reason why wire is moving, foreign bodies can migrate to other parts of the body by body motion over time. But, some researchers believes that the wires may have been misplaced in the muscle, lung, mediastinum, and heart because they could not migrate to those locations in normal circumstances[11].

To minimize the incidence of these complications and their sequelae, various precautions can be taken. First, during the localization procedure, the wire's hook should be placed inside the main mass. Otherwise, the wire can migrate when the patient moves because of the fat that accounts for a large portion of the breast. In this case, the wire went through the tumor, and the hooked tip of the wire might be located within the prepectoral fatty space. The wire migrated along the prepectoral space due to the patient's respiratory movements and operation procedure. It may have moved along with soft tissue to the subcutaneous tissue of the back. Fortunately, it did not cause major blood vessel or nerve damage. A wire in this location can produce severe complications if the vascular structures or brachial plexus are injured. Although migration of breast wire is unusual, physicians should consider the possibility of its occurrence. Second, the wire should be bent at an angle of 90° at the skin surface following localization. Third, the time between localization and surgery should be reduced. It is recommended to localize immediately before breast surgery. Surgeons must account for the entire length of wire following the procedure to avoid having retained wires or wire fragments. Fourth, it would better to use a wire from a pre-made medical product. Because we use a 23-gauze needle with hooked monofilament wire that was made by surgeon, it can move freely without resistance and is vulnerable to migration. Fifth, more recently, the available options for performing preoperative localization have expanded greatly and they include non-wire devices such as radioguided occult lesion localization, radioactive seed localization, intraoperative ultrasonography, and radiofrequency identification tags. Non-wire localization devices can be placed days in advance of the surgery, at the patient's convenience, to avoid wire-related challenges and complications[12].

To conclude, wire migration is infrequent, but surgeons should be careful of the migration of the wire to distant organs. All possible steps should be taken to minimize these complications.

The loss of a hooked wire can lead to fatal complications. Surgeons must consider the possibility of wire migration during breast cancer surgery, and the device must be found and removed.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huo Q, Shen ZY, Wu HT S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Gray RJ, Pockaj BA, Garvey E, Blair S. Intraoperative Margin Management in Breast-Conserving Surgery: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hall FM, Frank HA. Preoperative localization of nonpalpable breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Helvie MA, Ikeda DM, Adler DD. Localization and needle aspiration of breast lesions: complications in 370 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:711-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bronstein AD, Kilcoyne RF, Moe RE. Complications of needle localization of foreign bodies and nonpalpable breast lesions. Arch Surg. 1988;123:775-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Seifi A, Axelrod H, Nascimento T, Salam Z, Karimi S, Avestimehr S, Ohebsion J. Migration of guidewire after surgical breast biopsy: an unusual case report. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bachir N, Lemaitre J, Lardinois I. Intrathoracic hooked wire migration managed by minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery. Acta Chir Belg. 2020;120:186-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Grassi R, Romano S, Massimo M, Maglione M, Cusati B, Violini M. Unusual migration in abdomen of a wire for surgical localization of breast lesions. Acta Radiol. 2004;45:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Banitalebi H, Skaane P. Migration of the breast biopsy localization wire to the pulmonary hilus. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:28-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | D'Orsi CJ, Swanson RS, Moss LJ, Reale FR, Wertheimer MD. A complication involving a braided hook-wire localization device. Radiology. 1993;187:580-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Montrey JS, Levy JA, Brenner RJ. Wire fragments after needle localization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1267-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Azoury F, Sayad P, Rizk A. Thoracoscopic management of a pericardial migration of a breast biopsy localization wire. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87: 1937-1939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kapoor MM, Patel MM, Scoggins ME. The Wire and Beyond: Recent Advances in Breast Imaging Preoperative Needle Localization. Radiographics. 2019;39:1886-1906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |