Published online Sep 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7857

Peer-review started: March 30, 2021

First decision: June 7, 2021

Revised: June 8, 2021

Accepted: July 30, 2021

Article in press: July 30, 2021

Published online: September 16, 2021

Processing time: 164 Days and 6.7 Hours

Globally, the estimated annual incidence of snakebites is approximately 5 million, and approximately 100000 deaths occur from snakebites annually. Local tissue reaction, haemorrhagic clotting disorder, nephrotoxicity, and neurotoxicity are very common effects of snake envenomation, but other rarer complications, such as thrombosis, may also occur as a result of underlying disease. In the treatment of snakebite patients, attention should be paid to the patient’s underlying diseases to avoid serious and catastrophic consequences secondary to snakebite.

We report a 69-year-old man with critical right lower extremity pain after left foot snakebite 10 d prior without intermittent claudication or atrial fibrillation history. He was diagnosed with acute right lower extremity arterial thrombosis, which may have been caused by coagulopathy after snakebite and lower extremity atherosclerotic occlusive disease. Lower extremity computed tomography angiography at another hospital revealed that the aortoiliac and femoral arteries had neither filling defects nor atherosclerosis, but the right popliteal artery was occluded 2.3 cm below the tibial plateau. The patient received emergency catheter-directed thrombolysis, but amputation was carried out 11 d after admission because the patient had been admitted to the hospital too late to save the extremity.

Acute ischaemia of the lower extremity due to snakebite is a rare event, and physicians should bear in mind the serious complications that may occur, especially in patients with atherosclerotic disease.

Core Tip: We report a 69-year-old man who presented with critical right lower extremity pain and was diagnosed with acute right lower extremity arterial thrombosis that may be caused by coagulopathy after snakebite and arteriosclerosis in lower extremity. Haematological abnormalities are very common with snakebites, but thrombotic manifestations are less common. Physicians should bear in mind the rare complications and devastating sequela of extremity ischemia following snakebite, especially for patients with atherosclerotic disease.

- Citation: Lu ZY, Wang XD, Yan J, Ni XL, Hu SP. Critical lower extremity ischemia after snakebite: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(26): 7857-7862

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i26/7857.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7857

Snake envenomation can result in local tissue reactions, coagulopathy, neurotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity[1]. However, thrombotic manifestations are relatively rare. We report a 69-year-old man with acute right lower extremity arterial thrombosis caused by snakebite.

A 69-year-old man presented to our facility with critical right lower extremity pain accompanied by gangrene of the right toes.

The symptoms had started 5 d prior to admission.

The patient had been bitten by a viper 2 wk prior. He showed no symptoms of shock or hemorrhage after snakebite, and he was sent to a local hospital to be injected with antivenom 3 h later. There was no other relevant past history.

No personal or family history was identified.

Vital sign measurements showed that the blood pressure was 117/65 mmHg and heart rate was 78 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed a 3 cm × 2 cm ulcerated area with a haemorrhagic crust on the left dorsum (Figure 1A); the right foot showed blackening of the skin, accompanied by blister formation and exudate. Tissue necrosis was found on the toes (Figure 1B). There was a normal pulse in the left lower limb arteries and right femoral and popliteal arteries, but the right posterior and dorsal pedal arteries had no pulse.

The laboratory results showed a fibrinogen level of 5.50 g/L and D-dimer level of 0.89 mg/L, and normal activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, prothrombin time, and platelet count.

Lower extremity computed tomography angiography revealed that the aorto-iliac and femoral arteries had neither a filling defect nor atherosclerosis, but the right popliteal artery was occluded 2.3 cm below the tibial plateau (the patient did not have a computed tomography film available because the scan was performed at another hospital).

With a history of snakebite and the exclusion of embolic diseases, the patient was diagnosed with acute right lower extremity arterial thrombosis and lower extremity atherosclerotic occlusive disease.

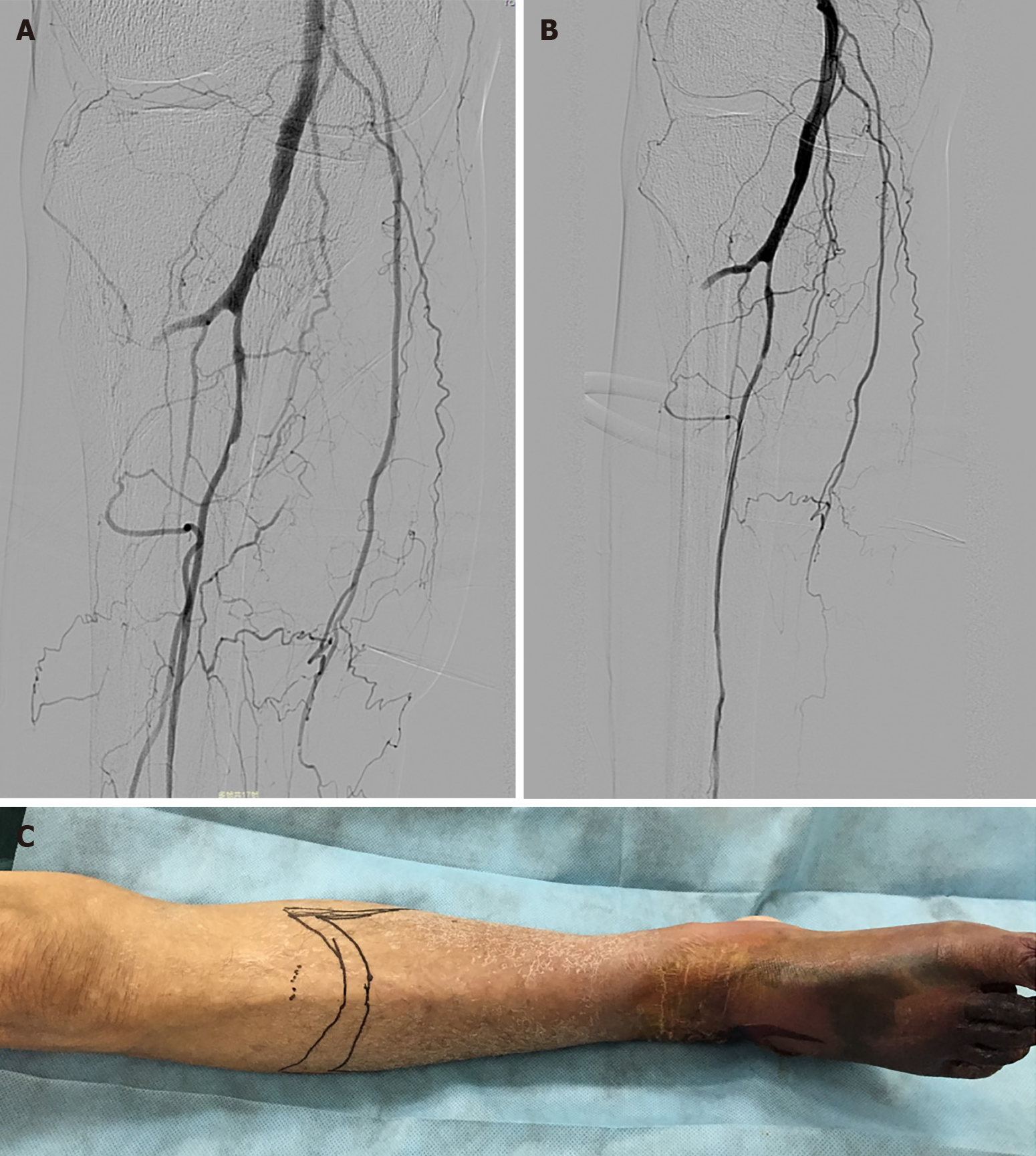

The patient received anticoagulant therapy immediately after admission to our hospital. In an attempt to salvage the limb, the patient was sent promptly for emergent right lower extremity angiography. The guide wire met with resistance when passing through the right popliteal artery; the distal popliteal artery was not visible on angiography, and a large number of lateral branches could be seen (Figure 2). Then he received a 6-d course of catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) [a bolus of 300000 U urokinase (UK) was given via the catheter with the pulse spray technique in the first operation, followed by a continuous intra-arterial UK infusion at a rate of 50000 U/h through the infusion catheter], therapeutic dose of anticoagulant therapy, and percutaneous balloon dilatation percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty (PTA) of the right anterior tibial and peroneal arteries, but the outflow was not significantly improved after PTA (Figure 3A and B). The patient underwent an amputation 9 cm below the right tibial plateau (Figure 3C).

Eventually, the patient fully recovered and was discharged from the hospital 21 d after admission. He was fitted with a prosthetic leg 6 mo after amputation.

Snake envenomation commonly causes local tissue reactions, coagulopathy, nephrotoxicity, and neurotoxicity[1-3]. Haematological abnormalities are very common with snakebite; however, thrombotic manifestations are very rare.

In a study in Sweden[4], deep vein thrombosis and myocardial infarction (MI) were less commonly reported complications. In another study[5], cerebral infarction, pulmonary embolism, and MI were common thrombotic events. Roplekar Satish reported a case in which venom caused haemodynamic disorders and abnormal coagulation in a patient, leading to MI[6]. In the present case, we initially believed that the patient’s lower extremity arterial thrombosis was due to the hypercoagulable state caused by snake venom, but the resistance that the guide wire encountered when passing through the lower limb arteries and the ineffectiveness of vascular recanalization after thrombolysis therapy suggested that the patient may have had local atherosclerotic stenosis occluded by a thrombus. This also explains why the patient's thrombotic event occurred in the contralateral limb rather than ipsilateral to the snakebite.

Another issue to consider is what role anti-venom therapy played in this patient’s course. The patient showed no signs of shock or local or systemic bleeding after snakebite, which showed that venom did not cause hemorrhagic disorder. But he was unable to provide further detailed information, such as blood coagulation function changes before and after antivenin injection, therefore we cannot judge the role of antivenom in the development of the patient’s conditions. We guess that the most likely thing is that venom caused the patient's hypercoagulable state, but the antivenom partially alleviated this coagulation dysfunction, so the patient's ischemia was limited to the calf. It reminds us that we need to collect more information when we encounter rare cases in future.

Emergency revascularization is necessary for patients with acute limb ischaemia (ALI) that threatens the survival of the limb[7]. CDT is the preferred method of delivery for ALI[8], especially for ALI with a history of less than 14 d and without movement disorders[9]. The patient missed the optimal time window for treatment. However, CDT treatment enabled a lower plane of amputation, preserved the function of the knee, and enhanced the patient’s quality of life.

The mechanism behind thrombotic complications is thought to be the imbalance between the anti-coagulant and pro-coagulant systems in body. The risk of life-threatening bleeding is a major issue with thrombolysis in the context of snakebite, which is known to cause consumption coagulopathy[10]. Changes in coagulation indices as well as clinical symptoms and signs should be closely monitored during thrombolytic therapy. This case showed no manifestations of bleeding or haemo

Acute ischaemia of the lower extremity due to snakebite is a rare event, but physicians should bear in mind the serious complications and the devastating sequela of lower limb ischaemia following snakebite, especially in patients with atherosclerotic disease.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sung WY S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Maheshwari M, Mittal SR. Acute myocardial infarction complicating snake bite. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:63-64. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Razok A, Shams A, Yousaf Z. Cerastes cerastes snakebite complicated by coagulopathy and cardiotoxicity with electrocardiographic changes. Toxicon. 2020;188:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim JS, Yang JW, Kim MS, Han ST, Kim BR, Shin MS, Lee JI, Han BG, Choi SO. Coagulopathy in patients who experience snakebite. Korean J Intern Med. 2008;23:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Karlson-Stiber C, Salmonson H, Persson H. A nationwide study of Vipera berus bites during one year-epidemiology and morbidity of 231 cases. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2006;44:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thomas L, Tyburn B, Bucher B, Pecout F, Ketterle J, Rieux D, Smadja D, Garnier D, Plumelle Y. Prevention of thromboses in human patients with Bothrops lanceolatus envenoming in Martinique: failure of anticoagulants and efficacy of a monospecific antivenom. Research Group on Snake Bites in Martinique. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Niraj M, Jayaweera JL, Kumara IW, Tissera NW. Acute myocardial infarction following a Russell's viper bite: a case report. Int Arch Med. 2013;6:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fluck F, Augustin AM, Bley T, Kickuth R. Current Treatment Options in Acute Limb Ischemia. Rofo. 2020;192:319-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Björck M, Earnshaw JJ, Acosta S, Bastos Gonçalves F, Cochennec F, Debus ES, Hinchliffe R, Jongkind V, Koelemay MJW, Menyhei G, Svetlikov AV, Tshomba Y, Van Den Berg JC; Esvs Guidelines Committee; de Borst GJ, Chakfé N, Kakkos SK, Koncar I, Lindholt JS, Tulamo R, Vega de Ceniga M, Vermassen F, Document Reviewers, Boyle JR, Mani K, Azuma N, Choke ETC, Cohnert TU, Fitridge RA, Forbes TL, Hamady MS, Munoz A, Müller-Hülsbeck S, Rai K. Editor's Choice - European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Acute Limb Ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59:173-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 48.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Writing Committee Members. Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, Barshes NR, Corriere MA, Drachman DE, Fleisher LA, Fowkes FGR, Hamburg NM, Kinlay S, Lookstein R, Misra S, Mureebe L, Olin JW, Patel RAG, Regensteiner JG, Schanzer A, Shishehbor MH, Stewart KJ, Treat-Jacobson D, Walsh ME; ACC/AHA Task Force Members, Halperin JL, Levine GN, Al-Khatib SM, Birtcher KK, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Cigarroa JE, Curtis LH, Fleisher LA, Gentile F, Gidding S, Hlatky MA, Ikonomidis J, Joglar J, Pressler SJ, Wijeysundera DN. 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients with Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary. Vasc Med. 2017;22:NP1-NP43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Satish R, Kanchan R, Yashawant R, Ashish D, Kedar R. Acute MI in a stented patient following snake bite-possibility of stent thrombosis - a case report. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |