Published online Sep 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7811

Peer-review started: February 24, 2021

First decision: June 15, 2021

Revised: June 20, 2021

Accepted: July 30, 2021

Article in press: July 30, 2021

Published online: September 16, 2021

Processing time: 197 Days and 16.4 Hours

Pediatric temporal fistulae are rarely reported in the literature. Dissemination of these cases can help inform future diagnosis and effective treatment.

Three pediatric patients came to the clinic due to repeated infections of the skin and soft tissue of the temporal area. One patient presented with a temporal fistula that penetrated the temporal bone and reached the dura mater. Another patient presented with a temporal fistula that penetrated into the temporal muscle fascia. The third patient presented with a fistula that penetrated the lateral wall of the orbit and entered the orbit. All patients underwent surgical fistula resection informed by preoperative computed tomography (CT) evaluation. Histopathological evaluation was also performed. All three patients were surgically treated successfully. Histopathological evaluations confirmed the fistula diagnoses in all three cases.

For patients who have temporal fistulae with repeated infections, surgical treatment should be performed as soon as possible to prevent serious complications. CT can be very useful for preoperative evaluation. B-mode ultrasound examination and evaluation also have a certain auxiliary role.

Core Tip: For patients who have temporal fistulae with repeated infections, surgical treatment should be performed as soon as possible to prevent serious complications. Computed tomography can be very useful for preoperative evaluation.

- Citation: Gu MZ, Xu HM, Chen F, Xia WW, Li XY. Pediatric temporal fistula: Report of three cases. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(26): 7811-7817

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i26/7811.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i26.7811

Common fistula lesions occurring in the pediatric maxillofacial region include congenital preauricular fistulae, first branchial cleft fistulae, and nasal fistulae. To date, few reports of pediatric temporal fistulae exist in the literature. In the early embryonic stage, the epidermis of the head and the dura mater merge, separating when the skull bone is formed. Adhesion, if any, can result in epidermis residue in the deep tissues, forming a cyst. If the invaginated epidermis is not completely embedded but connected to the scalp, a congenital fistula can form[1,2]. This article details three pediatric cases of temporal fistulae, discussing their diagnosis and treatment along with a review of the existing literature. From July 2017 to September 2019, three pediatric patients with temporal fistulae were admitted and treated at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery of Shanghai Children's Hospital. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of the three patients, including sex, age, medical history, location, lesion size, computed tomography (CT) examination, and surgical and pathological examinations.

Case 1: A 4-year and 10-mo-old girl presented with a pinpoint-like lesion in her left temporal region since birth.

Case 2: A 1-year and 7-mo-old boy presented with a right temporal fistula that was noticed by his family member for 4 mo.

Case 3: A 10-year-old girl presented with right temporal fistula that was originally observed after birth.

Case 1: A 4-year and 10-mo-old girl presented with a pinpoint-like lesion in her left temporal region since birth. The lesion did not bother the patient in general. However, 1 year ago, the patient began to experience left temporal swelling and pain after catching a common cold. The symptoms improved after anti-inflammatory treatment at that time. Six months later, the patient experienced congestion, swelling, and pain in the left temporal soft tissue after a subsequent cold.

Case 2: A 1-year and 7-mo-old boy presented with a right temporal fistula that was noticed by his family member 4 mo ago. Three months after the initial detection, the skin around the fistula appeared red and swollen (approximately 1 cm in diameter) with mild tenderness but without any discharge. At that time, B-mode ultrasonography revealed a mixed echo area in the superficial soft tissue in the right temporal region (approximately 12.1 mm × 11.1 mm × 4.7 mm), with a border and no capsule. The fistula was incised and drained. Bean dregs-like tissue was also drained. His symptoms subsided after anti-inflammatory treatment, dressing changes, and symptomatic management. Follow-up B-mode ultrasonography showed no obvious abnormal echo under the skin of the right facial incision.

Case 3: A 10-year-old girl presented with right temporal fistula that was originally observed after birth. No redness, swelling, or pain were noted in the surrounding skin. Occasionally, white rice-like secretions from the fistula were observed. Due to the child’s young age, her family did not have the issue further examined. One year ago, the patient experienced an infection in the region above the right canthus. The surrounding skin became red and swollen, approximately 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm in size, with slight pain. Eye movement and vision were not affected. The abscess subsided when spontaneous ulceration occurred. A purulent discharge was seen after ulceration. The patient was diagnosed with chalazion at a local hospital, but no surgical intervention was pursued. Since the onset of the lesion, the child experienced infections on the right canthus twice every month and underwent abscess incision and drainage twice at a local hospital.

The patients had no other previous medical history.

The patients had no relevant family medical history.

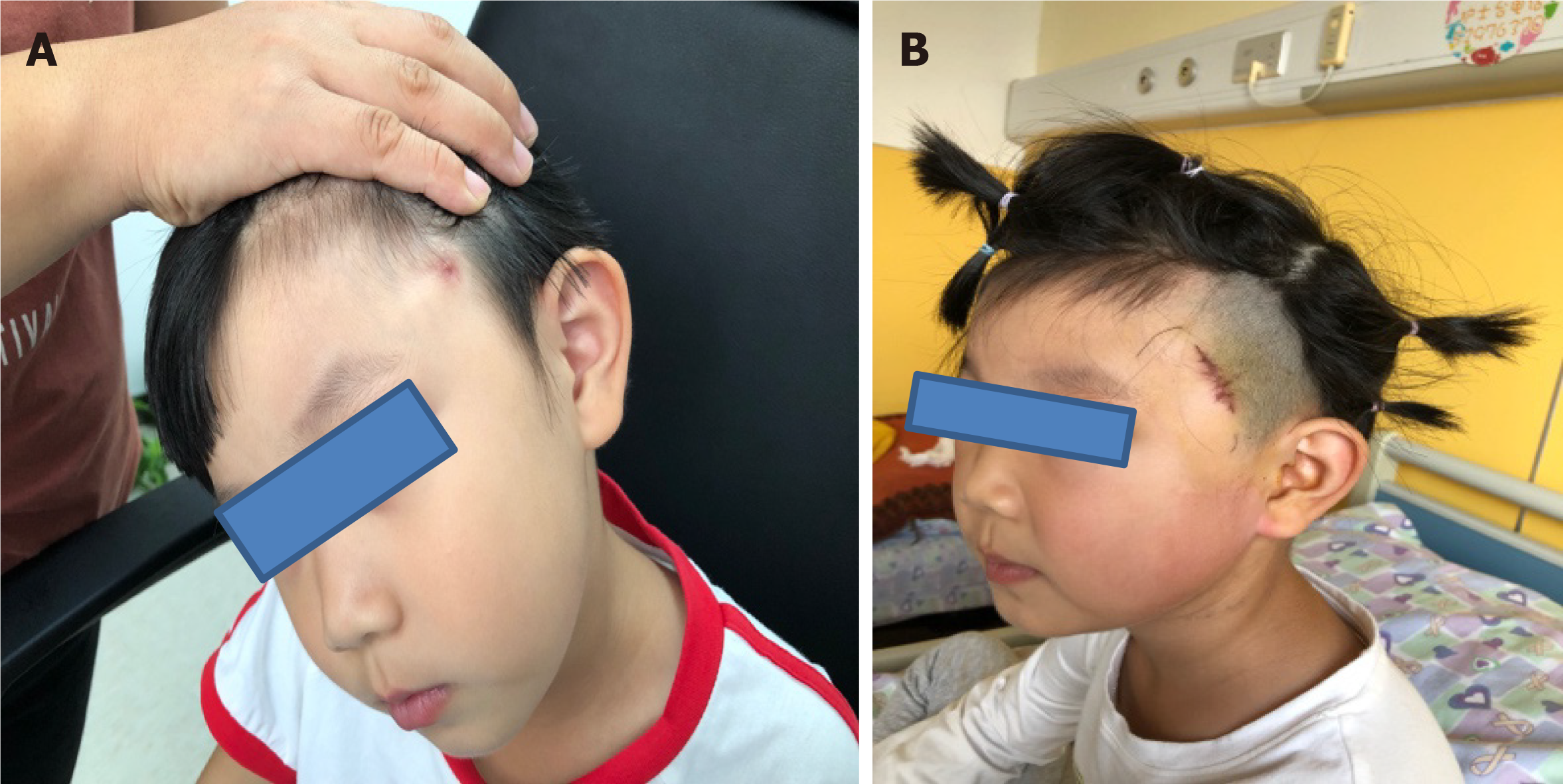

Case 1: Physical examination revealed a fistula near the upper edge of the left helix in the temporal region. The skin around the fistula was red and swollen, with obvious fluctuations. The redness and swelling subsided after incision and drainage of the abscess and anti-inflammatory treatment. Four months after the drainage, the abscess reformed, improving after a second round of drainage, anti-inflammatory treatment, and a dressing change. After that episode, inflammation of left temporal region (redness and swelling) recurred very often, improving after anti-inflammatory treatment was given. Upon physical examination, a fistula was once again observed in the left temporal region, with old scarring nearby. No local swelling or tenderness was noted (Figure 1).

Case 2: Physical examination showed a fistula in the right temporal region, from which no purulent secretion was seen. No redness, swelling, or pain in the surrounding skin was noted. A 1-cm-long scar was visible approximately 0.5 cm behind the fistula.

Case 3: Physical examination showed a fistula in the right temporal region, from which no purulent secretion was seen. No redness, swelling, or pain in the surrounding skin was noted. A granulation tissue nodule (approximately 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) was visible in the area above the right canthus.

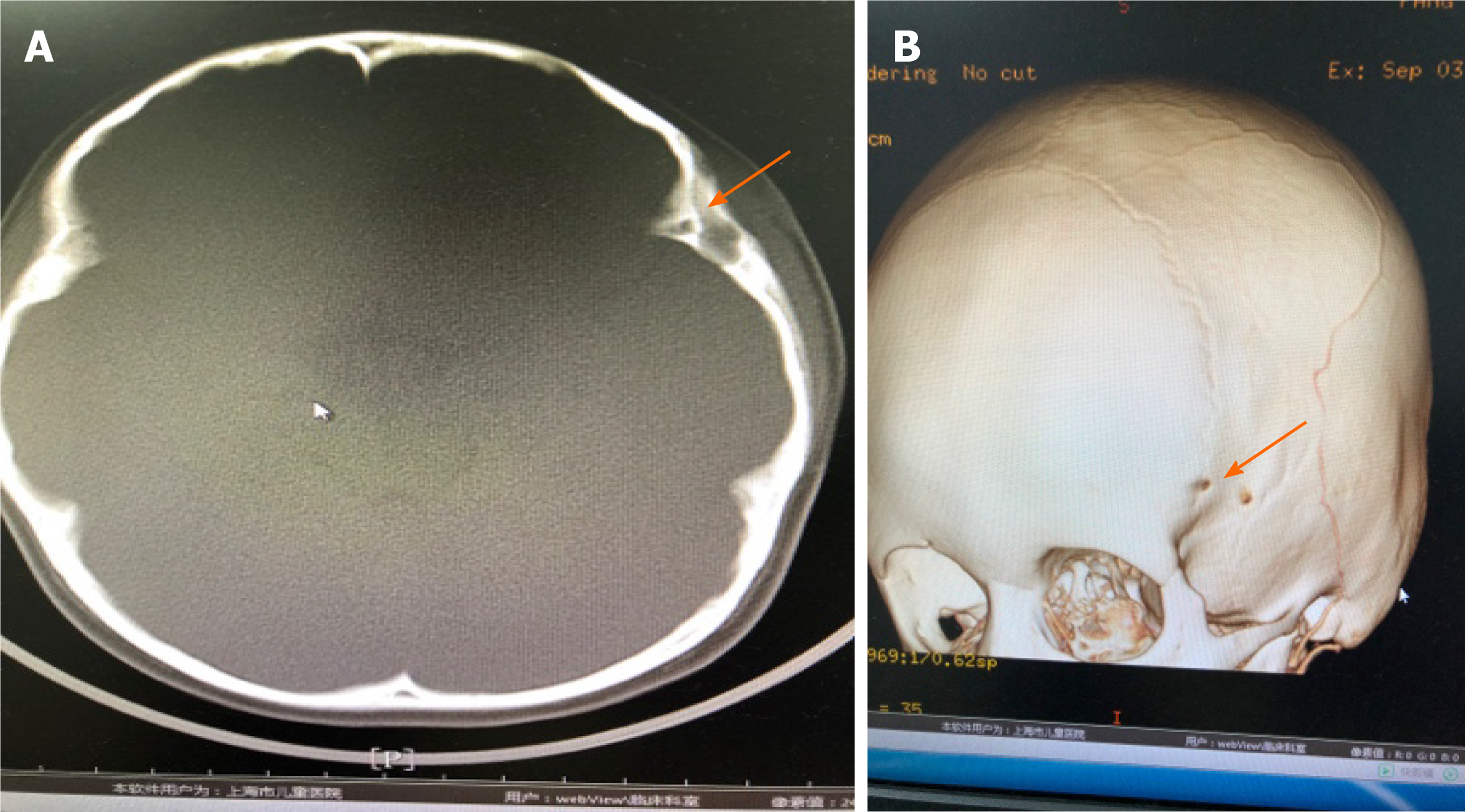

Case 1: Temporal contrast-enhanced CT showed an irregular, slightly low-density mass (approximately 15.28 mm × 5.64 mm × 14.16 mm) in the subcutaneous layer of the left frontotemporal junction region, which was considered to be mostly infectious. The density of the mass was uneven, and the edge of the lesion was enhanced with contrast. The lesion was mainly located in the subcutaneous layer and the edge was not well rounded or smooth. The bone around the fistula was smooth and intact with sclerosis. The local tubular fistula extended to the deep left temporal bone and seemed to penetrate the inner plate of the skull (Figure 2). Preoperative B-mode ultrasound suggested subcutaneous hypoechoic structures in the left temporal lobe, with a range of about 13.8 mm × 8.2 mm × 3.4 mm. A duct structure with a diameter of about 1.8 mm was seen inside this area. Color Doppler flow imaging detected no obvious blood flow signal in this area. B-ultrasonography showed a hypoechoic structure with fistula subcutaneously in the left temporal lobe.

Case 2: Temporal CT showed that the subcutaneous lesions in the right temporal region were considered to be mostly infectious (Figure 3).

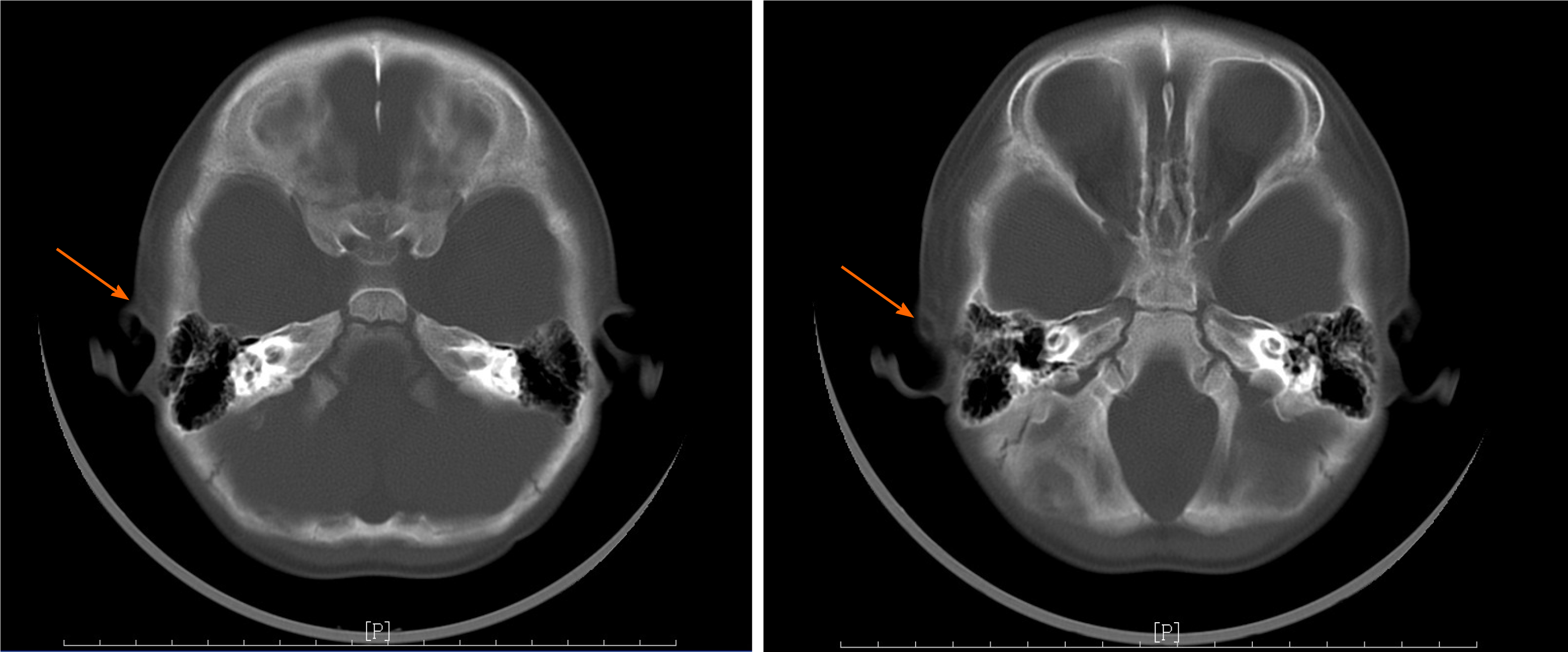

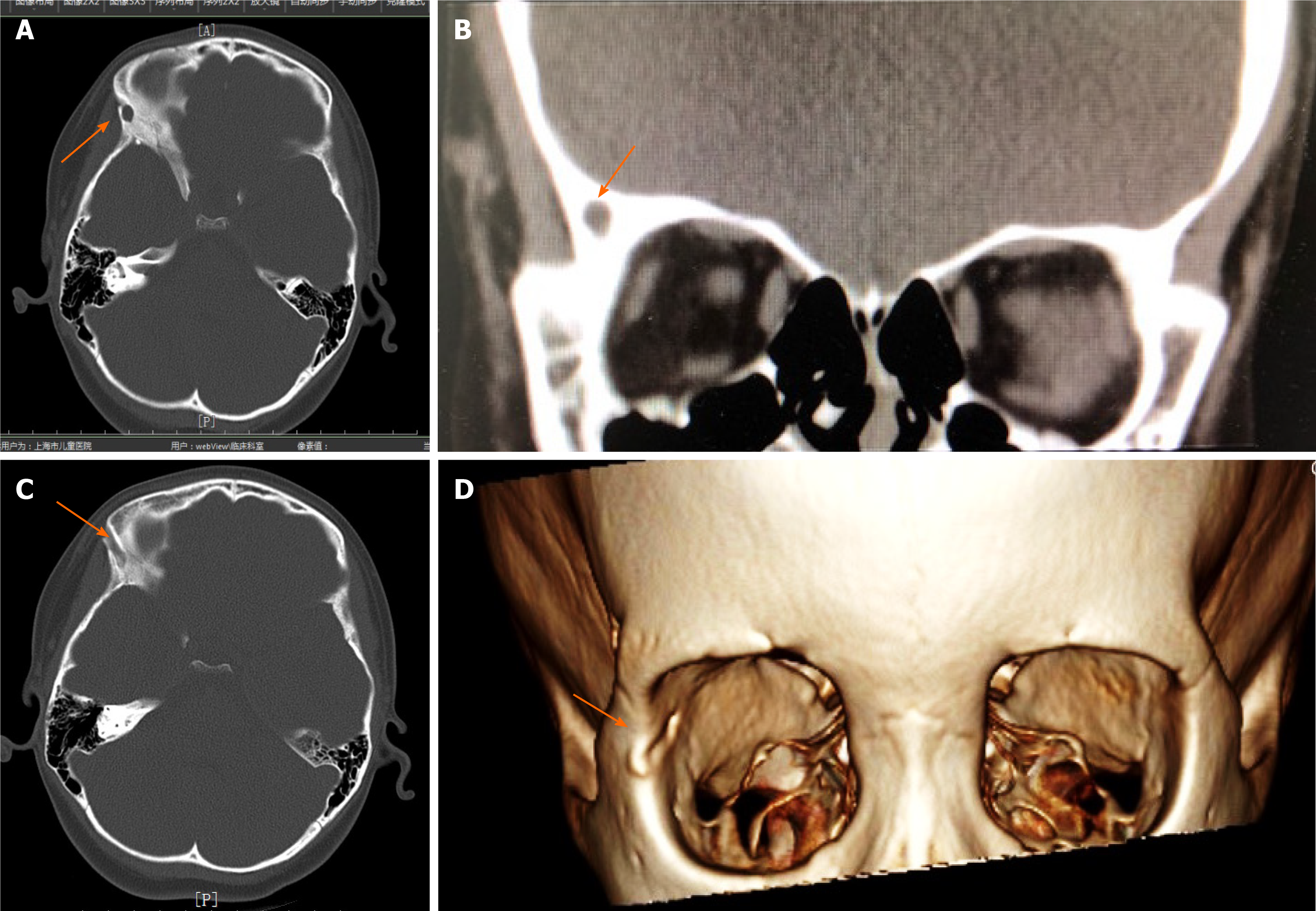

Case 3: CT showed the local subcutaneous soft tissue swelling in the right frontal area and possible sinus tract formation (Figure 4).

Based on the results of pathology, microscopy, and CT, the diagnoses were all temporal fistula.

Case 1: A fusiform incision was made along the fistula in front of the ear. The fistula was separated on the superficial temporal fascia until reaching the temporal bone. An absorption notch in the temporal bone around the fistula was noted. The skin sinus formed a cord into the temporal bone. An electric bone drill was used to remove the temporal bone above the fistula. The internal sinus tract of bone was approximately 1.5 cm in length, with partial elevation, containing bean dregs-like tissue and hair. The fistula was deeply adhered to the dura mater. The fistula was completely removed. After washing the surgical wound cavity, gelatin sponges were packed in the cavity and a drainage strip was placed. Anti-inflammatory and symptomatic treatments were provided following the surgery.

Case 2: A fusiform incision was made along the fistula to separate the skin and subcutaneous tissue. The fistula was separated until reaching the superficial temporal fascia. The fistula tissue was removed. After washing the surgical wound cavity, a drainage strip was placed. Anti-inflammatory and symptomatic treatments were provided following surgery.

Case 3: A 2-cm oblique incision was made along the fistula on the right temple to separate the skin and the fistula. The temporal fistula was approximately 3 cm long and extended to the orbital marginal temporal bone surface, which communicated with the intraorbital tissue through the zygomatic foramen. Then, an incision around the granulation tissue of the right upper eyelid was made to completely remove the granulated tissue. Removing the tissue allowed visualization of the fistula in the right upper eyelid traveling to the inside orbit along the lateral superior wall of the orbit. The fistula was completely removed. The surgical field was washed, and proper hemostasis was performed.

Case 1: At the outpatient revisit 1 mo after the operation, the wound healed well. After telephone follow-up, there was no recurrence. The patient recovered very well.

Case 2: The patient recovered very well. Postoperative pathology confirmed the fistula diagnosis. Microscopy showed skin tissue, fibrous tissue degeneration in the dermis, and small focal lymphocytic infiltration with granulomatous inflammation. At the outpatient revisit 1 mo after the operation, the wound healed well. After telephone follow-up, there was no recurrence.

Case 3: The patient recovered very well. Pathology confirmed the diagnoses of fistula and inflammatory lesions and showed a lumen structure composed of skin tissue lined with squamous epithelium with keratosis. The structure was also infiltrated with subepithelial inflammatory cells. At the outpatient revisit 1 mo after the operation, the wound healed well. After telephone follow-up, there was no recurrence.

During the embryonic period, congenital remnants of the ectoderm component on the surface of the cranial suture can remain in the developing orbital fissure or frontotemporal suture and continue to grow, forming a dermoid cyst around the orbit or the temple. If the invaginated epidermis is not completely embedded and connected to the skin surface, a congenital fistula can form. Most periorbital dermatoid cysts and epidermoid cysts are located deeply below the periosteum and closely attached to the frontozygomatic suture and frontoethmoidal suture. Most are round and slightly compress the surrounding bone.

Bartlett et al[3] retrospectively analyzed the data of 84 children with orbital or facial dermoid cysts and divided them into three groups according to anatomical location: Eyebrow or frontotemporal group, orbital group, and nasal ethmoid group. Fifty-four patients whose frontotemporal dermoid cysts grew slowly, with clear borders, were asymptomatic, and the cysts had no deep expansion. Routine direct resection can be performed without extensive preoperative examination. However, fistula cases were reported in the study. Bonavolontà et al[4] reported only two cases of skin fistula in their study that included 145 patients.

Similar cases have been reported by Hong[5], Scolozzi et al[6], Yang et al[7], and Yan et al[8]. In contrast, unlike dermoid cysts and fistulas in the frontotemporal area, nasal dermoid cysts usually appear as sinus tracts. Bartlett et al[3] reported nine cases of nasal dermoid cysts in children, of which seven presented with sinus tract cysts. In four of those seven children, the sinus tracts invaded the intracranial area. Pensler et al[9] reported 32 cases of nasal dermoid cysts; 14 patients presented with sinus tract cysts, and of those, six patients exhibited sinus tracts that invaded the intracranial area. Posnick et al[10] reported 14 cases of nasal dermoid cysts. Intracranial expansion was noted in five patients on preoperative imaging and confirmed by surgical exploration. A dermoid cyst or fistula that penetrates the temporal bone to the skull may be the source of recurrent infection. If the infection is not treated in a timely manner, a series of serious complications may occur, including temporal osteomyelitis, meningitis, intracranial abscess, etc.[6].

In the three cases reported in this article, all patients came to the clinic due to repeated infections of the skin and soft tissue of the temporal area, and postoperative pathology indicated fistula. One patient presented with a temporal fistula that penetrated the temporal bone and reached the dura mater. Another patient presented with a temporal fistula that penetrated to the temporal muscle fascia. The third patient presented with a fistula that penetrated the lateral wall of the orbit and entered the orbit. Due to the rarity of these lesions in clinical practice, misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis are very common. However, with full understanding of the lesion, diagnosis may be improved. Patients with a history of repeated infections of the temporal skin and soft tissue may be good candidates for physical examination for fistulae in the local skin and watery or bean dregs-like discharge. CT additionally can reveal lesion involvement in the temporal bones and orbital bones and determine the range of a fistula. B-mode ultrasound examination indicated the presence of a local fistula. Therefore, preoperative CT is important for the assessment of unusual fistulas or ill-defined dermoid cysts. B-mode ultrasound examination and evaluation have a certain auxiliary role.

During surgery, a fusiform incision around the fistula can successfully separate the skin and fistula tissue along the fistula to its root. In the case of a bone fistula, an electric drill is recommended for removal of the bone above the fistula and for complete removal of the fistula lesion. After washing the surgical field, a drainage strip should be placed. Anti-inflammatory treatment and dressing changes should follow surgery. Generally, the prognosis of this surgical method is good. Residual epithelial sinus can cause recurrence. Therefore, patients with fistulas who have recurrent episodes of temporal infections should be treated as soon as possible to prevent serious complications. CT can be very important for the preoperative evaluation of pediatric temporal fistulae. B-mode ultrasound examination and evaluation also have a certain auxiliary role.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Otorhinolaryngology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gokce E S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Jaiswal AK, Mahapatra AK. Giant intradiploic epidermoid cysts of the skull. A report of eight cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wei L, Wang R, Wang S, Jing J, Gao J, Zhang X. Diagnosis and treatment of diploic epidermoid cysts [J]. Zhongguo Weichuang Shenjingwaike Zazhi. 2006;11:418-420. |

| 3. | Bartlett SP, Lin KY, Grossman R, Katowitz J. The surgical management of orbitofacial dermoids in the pediatric patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91:1208-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bonavolontà G, Tranfa F, de Conciliis C, Strianese D. Dermoid cysts: 16-year survey. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;11:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hong SW. Deep frontotemporal dermoid cyst presenting as a discharging sinus: a case report and review of literature. Br J Plast Surg. 1998;51:255-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scolozzi P, Lombardi T, Jaques B. Congenital intracranial frontotemporal dermoid cyst presenting as a cutaneous fistula. Head Neck. 2005;27:429-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang Y, Wu Y, Wang G, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Liang Y, Wu D, Li H. Clinical diagnosis and treatment of intracranial frontotemporal dermoid cyst with cutaneous sinus tract: Report of 2 cases. Kouqianghemian Waike Zaizhi. 2008;6:303-305. |

| 8. | Yan C, Low DW. A Rare Presentation of a Dermoid Cyst with Draining Sinus in a Child: Case Report and Literature Review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e244-e248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pensler JM, Bauer BS, Naidich TP. Craniofacial dermoids. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:953-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Posnick JC, Bortoluzzi P, Armstrong DC, Drake JM. Intracranial nasal dermoid sinus cysts: computed tomographic scan findings and surgical results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:745-754; discussion 755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |