Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6956

Peer-review started: June 2, 2021

First decision: June 25, 2021

Revised: June 26, 2021

Accepted: July 2, 2021

Article in press: July 2, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 64 Days and 3.5 Hours

Ulnar nerve injury subsequent to a fracture of the distal radius is extremely rare compared to median nerve injury. Treatment of ulnar nerve injury after closed distal radial fracture is controversial. Reasonable surgical planning and careful postoperative management can improve the prognosis of patients.

We report two cases of ulnar nerve injury subsequent to fracture of the distal radius. Both patients were admitted to hospital. Both patients had persistent ulnar nerve compression syndromes. The first patient achieved rapid recovery by early nerve decompression surgery, while the second patient had no recovery at 2-3 mo after injury and had more severe symptoms. At 10 wk after injury, the second patient agreed to nerve decompression surgery. The second patient finally achieved a successful outcome after nerve decompression and neurolysis, although she still has residual symptoms.

For patients with ulnar nerve compression syndrome related to acute wrist fracture, if symptoms persist and signs of recovery are not observed, early release is necessary to prevent permanent neurological damage.

Core Tip: Although conservative management is successful in some mild cases of ulnar nerve injury subsequent to a fracture of the distal radius, ulnar nerve exploration, decompression and neurolysis remain the gold standard. If symptoms persist and signs of recovery are not observed, ultrasonography can confirm localization of the area of compression, and early release is necessary.

- Citation: Yang JJ, Qu W, Wu YX, Jiang HJ. Ulnar nerve injury associated with displaced distal radius fracture: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6956-6963

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6956.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6956

The median, ulnar and radial nerves cross the wrist to innervate the hand. Fracture of the distal radius may be complicated by injuries to these structures. Ulnar nerve injury subsequent to a fracture of the distal radius is extremely rare compared to median nerve injury. Bacorn and Kurtzke[1] reported only one case of ulnar nerve injury (0.05%) in 2000 patients with fracture of the distal radius. However, Soong and Ring[2] encountered ulnar nerve palsy in 5 adults with high-energy, widely displaced, distal radius fractures during a 2-year period, suggesting that this combination of injuries may be more common than previously recognized.

Initial treatment of acute ulnar nerve compression subsequent to a fracture of the distal radius is reduction of the fracture fragments. However, there is some controversy regarding the need for early nerve exploration of an ulnar nerve injury in a closed fracture. Some authors have reported that careful observation can lead to recovery[2,3], while others have reported that rapid recovery could be obtained with early decompression[4,5].

Case 1: A 59-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital due to a deformity of the wrist caused by a car accident approximately 6 h prior.

Case 2: A 55-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital because a deformity of the wrist approximately 4 h following a fall while walking.

Case 1: The patient suffered a car accident that caused her to fall on her outstretched left hand, which caused gross deformity of the wrist.

Case 2: The patient fell accidentally on her outstretched left hand while walking, which caused deformity of the wrist.

Cases 1 and 2: The patients were both previously healthy. They were nonsmokers and had no comorbidities such as diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, alcoholism or obesity. They had no problems with their involved hand before the injury.

Both patients had a free personal and family history.

Physical examination revealed severe swelling and tenderness in the left wrist and mild hyposthesia in the medial half of the ring finger and the little fingers.

Laboratory studies showed normal.

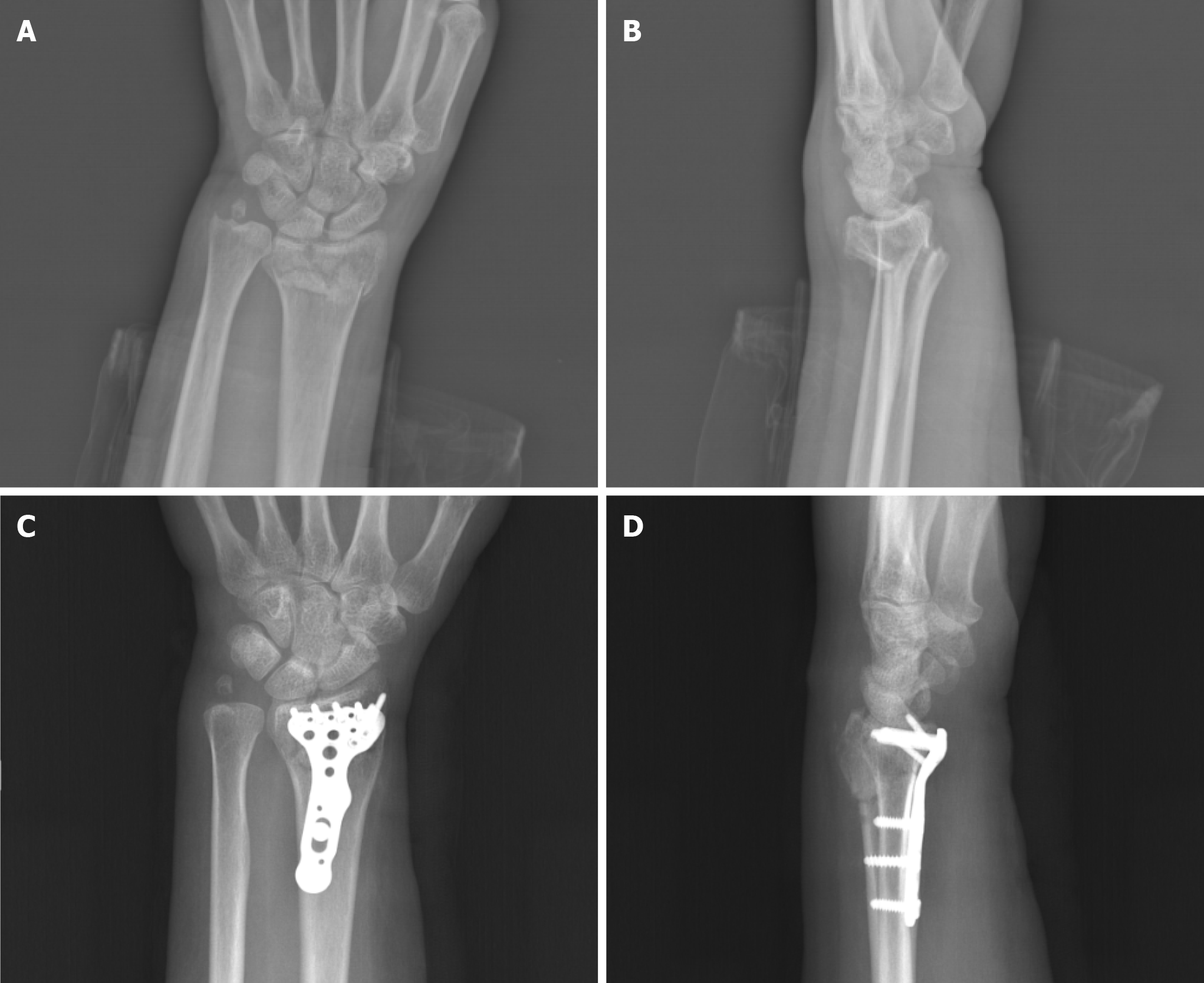

Case 1: Anteroposterior and lateral wrist radiographs revealed a left distal radial fracture involving the radial trunk, accompanied by dorsoradial displacement and an ulnar styloid fracture (Figure 1A and B).

Case 2: Anteroposterior and lateral wrist radiographs revealed a left distal radial intra-articular fracture, accompanied by dorsoradial displacement and an ulnar styloid fracture (Figure 2A and B).

The final diagnosis in both cases was closed fracture of the left distal radius with ulnar nerve injury.

One day after the injury, the patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation through a standard volar approach (Henry approach), using a standard volar locking plate (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR, United States) (Figure 1C and D). The bone deficiency in the radial metaphysis was treated with an allogeneic cancellous bone graft. The ulnar styloid fracture did not undergo internal fixation, and the ulnar nerve was neither explored nor released. The wrist was immobilized with a short arm cast. Unfortunately, after surgery, the patient complained of a continuous tingling sensation in the medial half of the ring finger and the little fingers, which gradually worsened. There was no clawing. The ultrasonographic findings showed that the continuity of the ulnar nerve was maintained, but there was significant swelling of the nerve with an anterior-posterior diameter of 3.8 mm and a left–right diameter of 4.3 mm (anterior-posterior diameter of the contralateral ulnar nerve was 1.6 mm and the left–right diameter was 2.0 mm) approximately proximal to the Guyon’s canal.

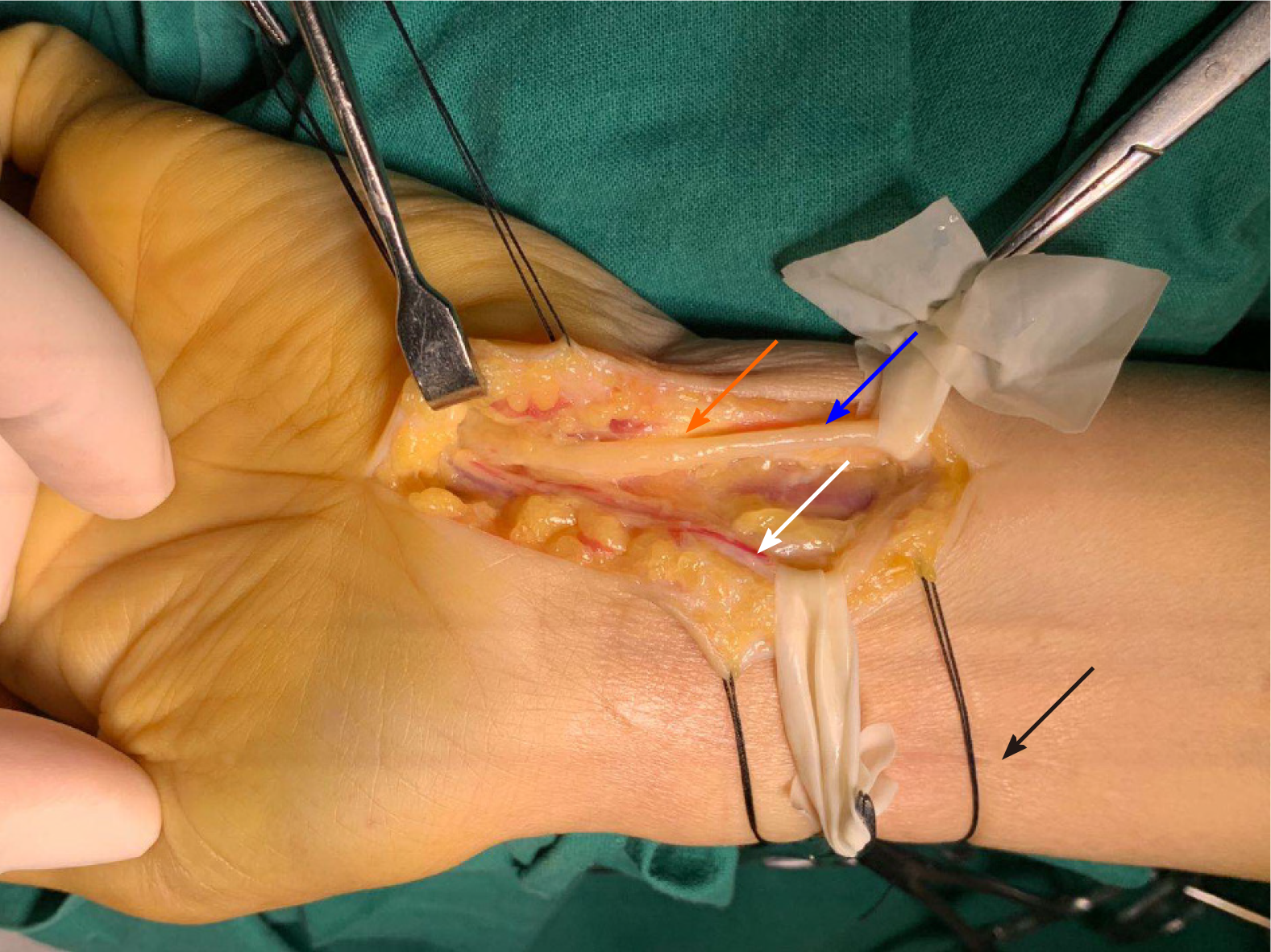

Six days after the injury, the patient underwent ulnar nerve exploration, and decompression and neurolysis were performed due to the gradual worsening of neurological symptoms. The intraoperative findings revealed contusion and swelling of the ulnar nerve and hematoma of the adjacent tissues (Figure 3). The principal branches of the ulnar nerve were identified and traced from proximal to the wrist to the bifurcation, and soft tissue obstruction of the ulnar nerve was released.

Two days after the injury, the patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation through a standard volar approach (Henry approach), using a standard volar locking plate (Acumed) (Figure 2C and D). The ulnar nerve was neither explored nor released. The wrist was immobilized with a short arm cast. After surgery, the patient still complained of a mild tingling sensation in the medial half of the ring finger and the little fingers, with no significant aggravation. There was no clawing. Due to the mild neurological symptoms, she denied further surgery and was discharged. At 2 wk after surgery, the short arm cast was removed, and the range of motion exercise was started. At 4 wk, no clawing was noted; however, at 5 wk, the patient presented with a claw hand. Due to the patient’s rejection of further surgery, a static anti-claw hand splint was given, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were recommended until 8 wk.

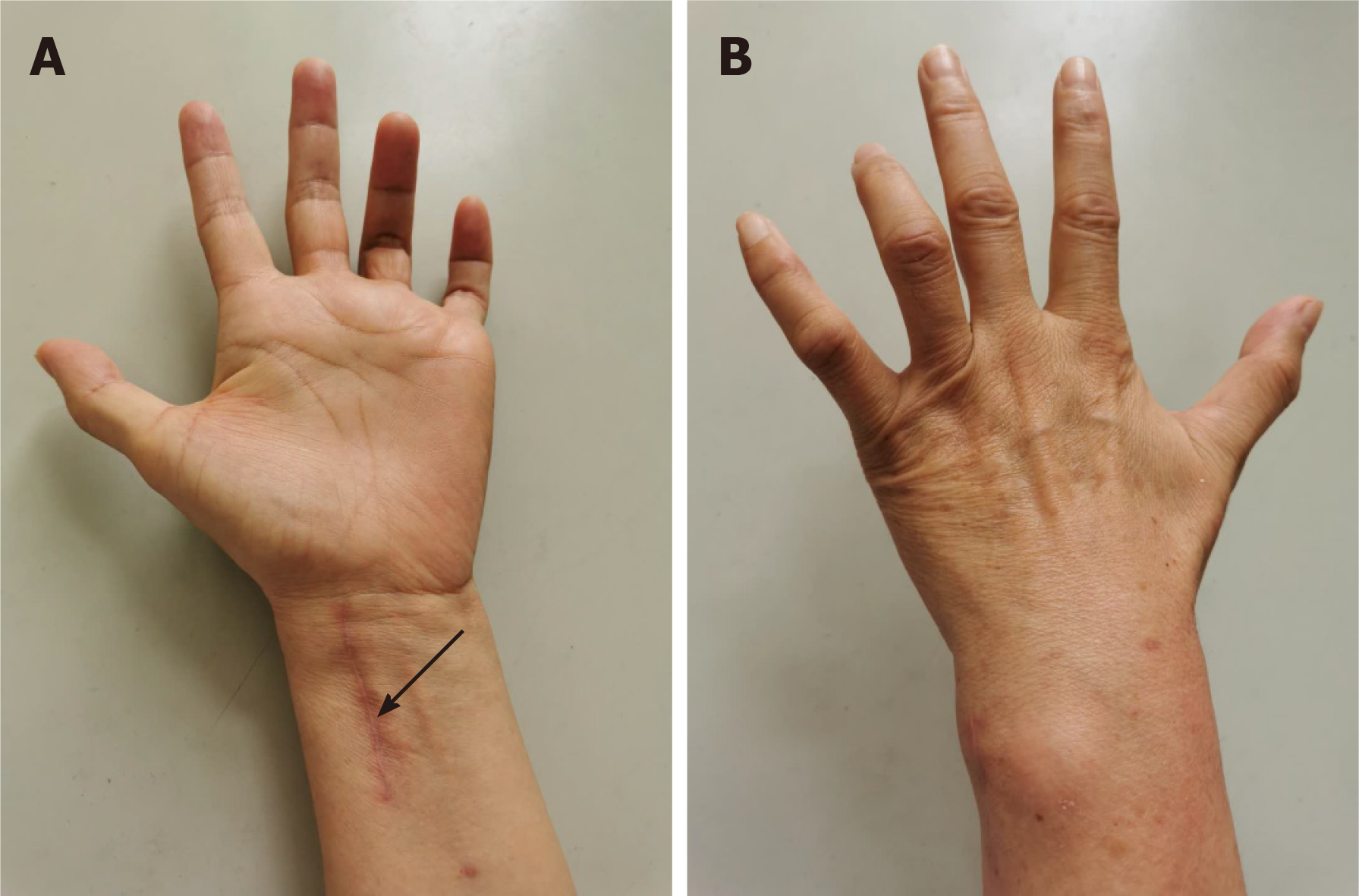

At 8 wk after surgery, the patient complained of numbness, and tingling in the small and ring fingers became more pronounced. Occasionally, she woke up during the night. During that period, she experienced weakness in the left hand, especially when grasping an object. In her detailed examination, a typical ulnar claw deformity was noted (Figure 4). The patient was positive for Froment’s sign. Tinel’s sign was positive on the volar ulnar side of the wrist and radiating to the ulnar two digits. The ultrasonographic findings showed that the continuity of the ulnar nerve was maintained, but there was significant swelling of the nerve with an anterior-posterior diameter of 3.0 mm and left-right diameter of 5.6 mm (anterior-posterior diameter of the contralateral ulnar nerve of 2.4 mm and left-right diameter of 3.6 mm) at the region proximal to the wrist joint, and an anterior-posterior diameter of 3.0 mm and left-right diameter of 4.3 mm (anterior-posterior diameter of the contralateral ulnar nerve of 2.2 mm and left-right diameter of 2.9 mm) in the Guyon’s canal.

Due to the more pronounced neurological symptoms, the patient agreed to further surgery. At 10 wk postoperatively, ulnar nerve exploration, decompression and neurolysis were performed. The intraoperative findings revealed ulnar nerve compression approximately proximal to the Guyon’s canal, in which the nerve was significantly swollen and adhered to the adjacent fibrous tissues (Figure 5). The principal branches of the ulnar nerve were identified and traced from proximal to the wrist to the bifurcation, and soft tissue obstruction of the ulnar nerve was released.

The neurological symptoms began to improve on the next day after nerve exploration (second operation). At 4 wk postoperatively, the ulnar nerve palsy had recovered comp

| Time | Information |

| August 8, 2018 | Admitted to hospital |

| August 9, 2018 | First surgery |

| August 13, 2018 | The ultrasonographic examinations |

| August 15, 2018 | Second surgery |

| August 17, 2018 | Discharged |

| September 15, 2018 | Recovered completely |

At 4 wk after the second operation, the neurological symptoms began to improve. At 6 mo after further surgery, the ulnar nerve palsy had recovered completely, but the minor claw hand deformity was still residual (by telephone follow-up) (Table 2).

| Time | Information |

| August 10, 2020 | Admitted to hospital |

| August 12, 2020 | First surgery |

| August 14, 2020 | Abandoned further surgery and discharged |

| September24, 2020 | Claw hand |

| October 16, 2020 | The ultrasonographic examinations |

| October 26, 2020 | Re-admission |

| October 28, 2020 | Second surgery |

| November 2, 2020 | Discharged |

| November 15, 2020 | The neurological symptoms began to improve |

| May 15, 2021 | The ulnar nerve palsy had recovered completely but the minor claw hand deformity was still residual |

Median nerve injury following fracture of the distal radius is a common neurological complication that is found in 2%-7% of cases and is associated with high-energy trauma. In contrast, ulnar nerve injury is an extremely rare event with only 30 cases reported worldwide[5]. This decreased susceptibility to injury is due to the anatomical differences between the nerves. At the level of the wrist, both the median and ulnar nerves are located within 3 mm from the radius. However, the median nerve is contained within the carpal tunnel, while the ulnar nerve courses superficial to the transverse carpal ligament and enters Guyon’s canal, making it less susceptible to compression.

The mechanisms of ulnar nerve injury associated with distal radius fracture include: Severing of the nerve over the sharp edge of the fractured radius; entrapment in the distal radioulnar joint; encasement of the nerve in scar tissue leading to tardive neuropathy and displacement of the nerve dorsal to the ulnar styloid[6]. Abbott and Saunders classified median-nerve injuries accompanying fractures of the distal part of the radius into four groups. Classification of ulnar nerve injuries is similar to that used for median neuropathies: Type 1, primary injuries, apparent immediately at the time of the injury; type 2, secondary injuries, following unstable or partial reduction and malunion; type 3, late on delayed injuries, occurring months or years after fracture healing and type 4, injuries following forced manipulation and immobilization[7].

In our study, both fractures resulted from a high-energy injury caused by a motorcycle accident and a fall from a height. The displacement was severe and combined with an ulnar styloid process fracture. In particular, the ulnar nerve compression syndrome of the two patients appeared immediately at the time of the injury. Thus, although there was no direct evidence of nerve injury caused by the ulnar fracture, ulnar fracture is more likely an indicator of severe injury, with potential for ulnar nerve injury. Case 1 had contusion of the ulnar nerve and hematoma of the adjacent tissues intraoperatively. It is believed that traction, contusion and residual hematoma are the main causes of primary trauma in a closed fracture. Secondary ulnar nerve lesions occur after the initial trauma, leading to progression of neuropathy. Case 2 had nerve swelling and adhesion to the adjacent tissues intraoperatively. It is believed that residual hematoma, subsequent local soft tissue edema and scars are the main causes of secondary ulnar nerve lesions.

The previously published cases predominantly involved young patients (average age, approximately 32 years)[8]. Unlike previously published cases, the two cases presented here were older women of 59 and 55 years. This indicated that the mechanisms of ulnar nerve injury associated with distal radius fracture predominantly include severe angulation on displacement and a coexistent ulnar fracture, and are not related to age.

In 1969, Shea and McClain[8] described three different types of ulnar nerve compression syndromes at the wrist based on the anatomical course of the nerve. Later, Gross and Gelberman’s cadaveric study delineated the relationship between the symptoms and three anatomical zones of ulnar nerve compression at the wrist[9]. Zone I is proximal to the bifurcation of the ulnar nerve; compression of which would lead to motor and sensory symptoms. Zone II includes the motor branch after its bifurcation, which would lead to purely motor symptoms. Zone III encompasses the superficial branch of the ulnar nerve, which would lead to only sensory symptoms[10]. Ultrasonographic scanning can confirm the diagnosis as well as localize the area of compression. In our study, both patients had early sensory symptoms. However, case 2 presented with motor and sensory symptoms at 5 wk, which helped delineate the level of compression at Zone I, which was confirmed by ultrasonography.

With regard to the treatment of an ulnar nerve injury after a closed distal radial fracture, there is some controversy. Vance and Gelberman[4] concluded that for patients with ulnar nerve compression syndrome related to acute wrist fracture, if dysesthesia does not improve within 24-36 h after reduction, surgical exploration with decompression should be considered. However, Soong and Ring[2] did not believe that early release was necessary, because these ulnar nerve injuries appear to be neurapraxia rather than pressure-related injuries.

In our study, the neurological symptoms of the two patients did not disappear after fracture reduction and fixation. Case 1 showed rapid recovery after early decompression, while case 2 had no recovery after 2-3 mo. Finally, case 2 achieved a successful outcome after nerve decompression and neurolysis, although she still had residual symptoms. We therefore agree that immediate surgical exploration is indicated in the event of a complete ulnar nerve injury that presents after reduction or operative fracture repair[11].

Although an ulnar nerve injury following a fracture of the distal radius is rare, it is important to pay more attention to its diagnosis and treatment. The direct neurological insults are associated with high-energy injuries and severe fracture displacement, while the secondary neurological insults are associated with edema and hematoma. Initial management with reduction and immobilization is indicated in all cases, because fracture reduction and measures that control edema usually alleviate this compression. Although conservative management is successful in some mild cases, ulnar nerve exploration, decompression and neurolysis remain the gold standard. If symptoms persist, and signs of recovery are not observed, ultrasonography can confirm localization of the area of compression, and early release is necessary.

We recommend that for patients with ulnar nerve compression syndrome related to acute wrist fracture, if symptoms persist and signs of recovery are not observed, early release is necessary to prevent permanent neurological damage.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Marickar F S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Bacorn RW, Kurtzke JF. Colles' fracture; a study of two thousand cases from the New York State Workmen's Compensation Board. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A:643-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soong M, Ring D. Ulnar nerve palsy associated with fracture of the distal radius. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:113-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Zoëga H. Fracture of the lower end of the radius with ulnar nerve palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1966;48:514-516. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Vance RM, Gelberman RH. Acute ulnar neuropathy with fractures at the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:962-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cho CH, Kang CH, Jung JH. Ulnar nerve palsy following closed fracture of the distal radius: a report of 2 cases. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2:55-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Davis DI, Baratz M. Soft tissue complications of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2010;26:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kozin SH, Wood MB. Early soft-tissue complications after fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:144-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shea JD, McClain EJ. Ulnar-nerve compression syndromes at and below the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:1095-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gross MS, Gelberman RH. The anatomy of the distal ulnar tunnel. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;238-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scarborough A, MacFarlane RJ, Mehta N, Smith GD. Ulnar tunnel syndrome: pathoanatomy, clinical features and management. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cooney WP 3rd, Dobyns JH, Linscheid RL. Complications of Colles' fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |