Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6872

Peer-review started: April 15, 2021

First decision: May 10, 2021

Revised: May 20, 2021

Accepted: May 26, 2021

Article in press: May 26, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 112 Days and 1.8 Hours

Trismus is a common problem with various causes. Any abnormal conditions of relevant anatomic structures that disturb the free movement of the jaw might provoke trismus. Trismus has a detrimental effect on the quality of life. The outcome of this abnormality is critically dependent on timely diagnosis and treatment, and it is difficult to identify the true origin in some cases. We present a rare case of trismus due to fungal myositis in the pterygoid muscle, excluding any other possible pathogenesis.

The patient presented with a 2-mo history of restricted mouth opening. Computed tomography showed obvious enlargement of the left pterygoid muscles. Furthermore, the patient had trismus without obvious predisposing causes. The primary diagnosis was pterygoid myosarcoma. Consequently, lesionectomy of the left pterygoid muscle was performed. Intraoperative frozen biopsy implied the possibility of an uncommon infection. Postoperative pathologic examination confirmed myositis and necrosis in the pterygoid muscle. Fungi were detected in both muscle tissue and surrounding necrotic tissue. The patient recovered well with antifungal therapy and mouth opening exercises. The rarity of fungal myositis may be responsible for the misdiagnosis. Although the origin of pathogenic fungi is still unknown, we believe that both hematogenous spread and local invasion could be the most likely sources. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature that reported fungal myositis in pterygoid muscles as the only reason that results in trismus.

Surgeons should remain vigilant to the possibility of trismus originating from fungal myositis.

Core Tip: Trismus has a detrimental effect on the quality of life. Early diagnosis and treatment have the potential to minimize the consequences of this condition. However, it is not always easy to identify the true origin in some cases. We report the first case in the literature that fungal myositis in pterygoid muscles is the only reason for trismus. We initially misdiagnosed this case of fungal origin because of its rarity. Surgeons should consider the possibility of fungal myositis in trismus diagnosis.

- Citation: Bi L, Wei D, Wang B, He JF, Zhu HY, Wang HM. Trismus originating from rare fungal myositis in pterygoid muscles: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6872-6878

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6872.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6872

Trismus refers to a severely restricted mouth opening of different etiologies. In most cases, trismus is the result of sustained contraction of the masticatory muscles. This abnormality has a negative impact on the quality of life. Early diagnosis and treatment have the potential to minimize the consequences of this condition. However, there are some special cases with rare origins that are difficult to identify.

Herein, we report the first case of trismus originating from fungal myositis in the pterygoid muscle.

A 58-year-old Chinese female presented with a 2-mo history of restricted mouth opening that gradually aggravated with pain 2 wk before admission. The patient had difficulty speaking and chewing.

The patient had trismus without obvious predisposing causes. The symptoms started 2 mo prior, which had gradually exacerbated. The patient did not receive any treatment before her first clinic visit.

The patient was healthy. She denied any history of immunodeficiency throughout the illness.

No personal or family history of fungal myositis or trismus exists.

On admission, her mouth opening was less than 10 mm. Her face was symmetrical. She felt pain when palpated in the left preauricular region. Her vital signs were within normal range.

Pathoglycemia (fiber Bragg grating = 10.75 mmol/L) and hyperglycosuria (UGLU = 56 mmol/L) were implicated in routine blood tests. Her white blood cell count was normal. Ketone body was detected in her urine (U-Ket = 15 mmol/L).

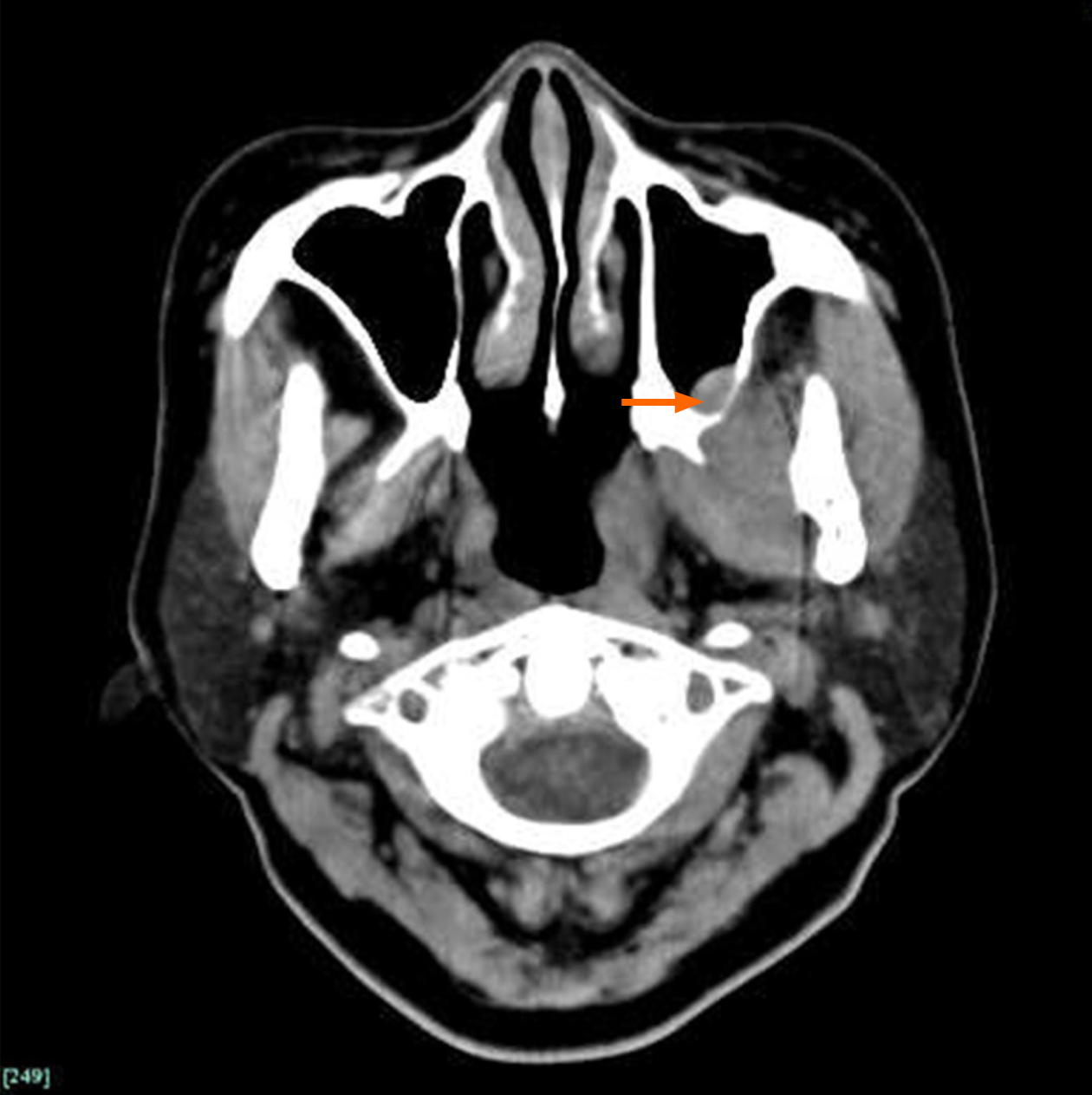

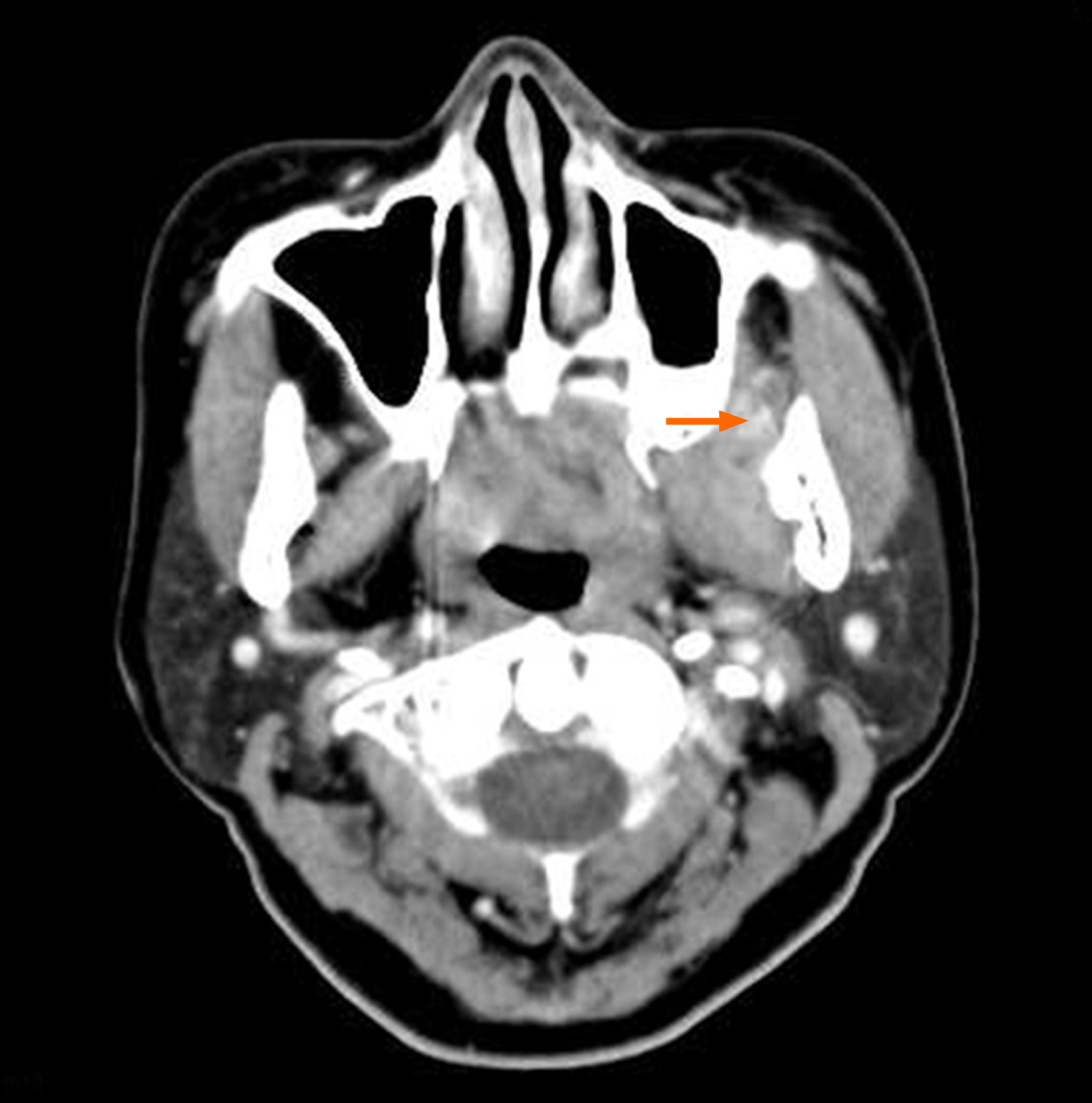

Computed tomography (CT) revealed obvious enlargement of the left pterygoid muscles. The boundary between the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles was obscure (Figure 1). Patchy enhancement was observed in muscles after intravenous injection of a contrast agent (Figure 2). Bone destruction and thickened mucous membrane on the maxillary sinus back wall, which was very close to the pterygoid muscle, were also seen on CT.

The primary diagnosis of left pterygoid myosarcoma and diabetes was established. Glucose-lowering medications were immediately administered to the patient. Consequently, lesionectomy of the left pterygoid muscles was scheduled under good glucose control. However, the repeated intraoperative frozen biopsy did not validate the original diagnosis and implied the possibility of an uncommon infection.

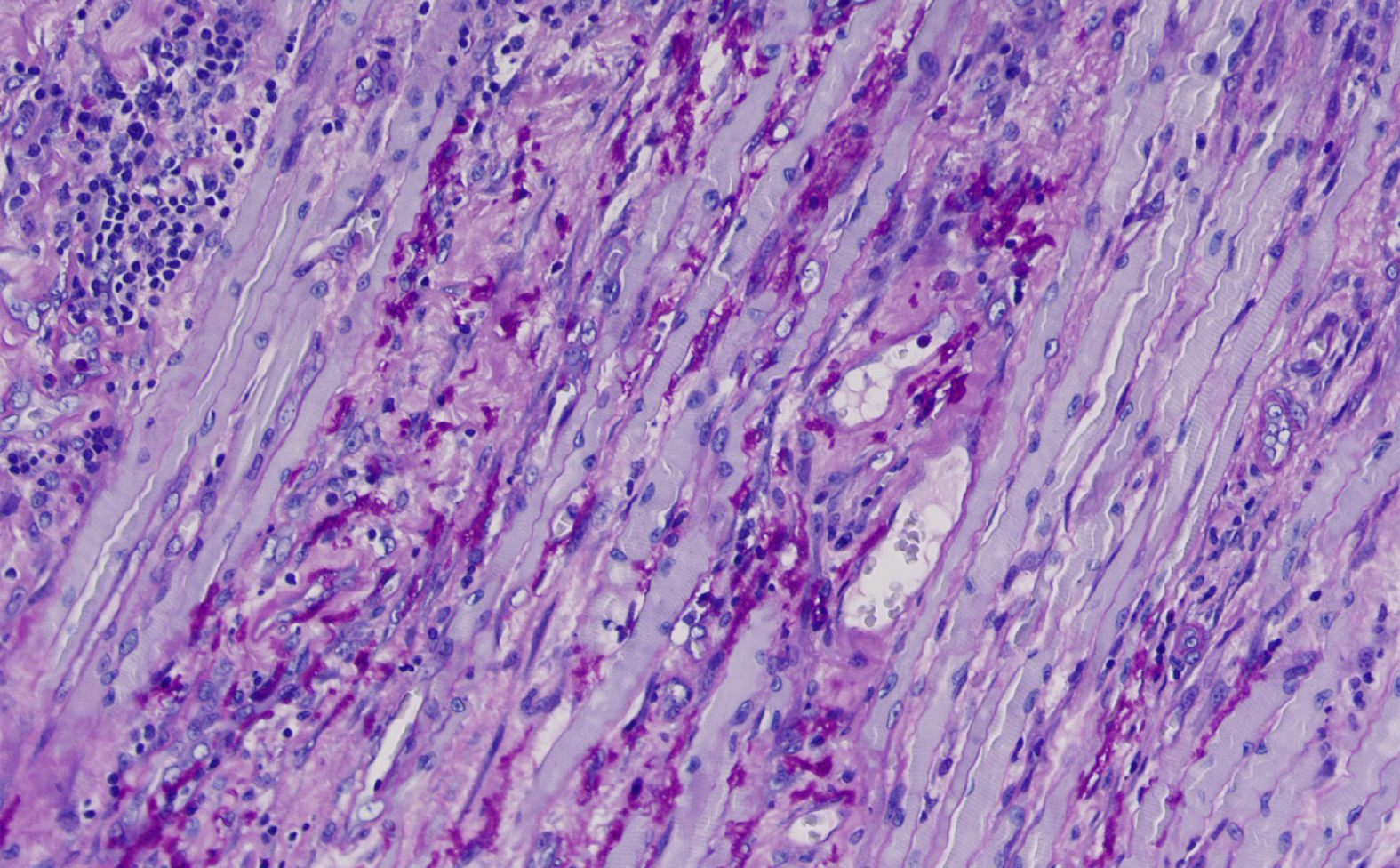

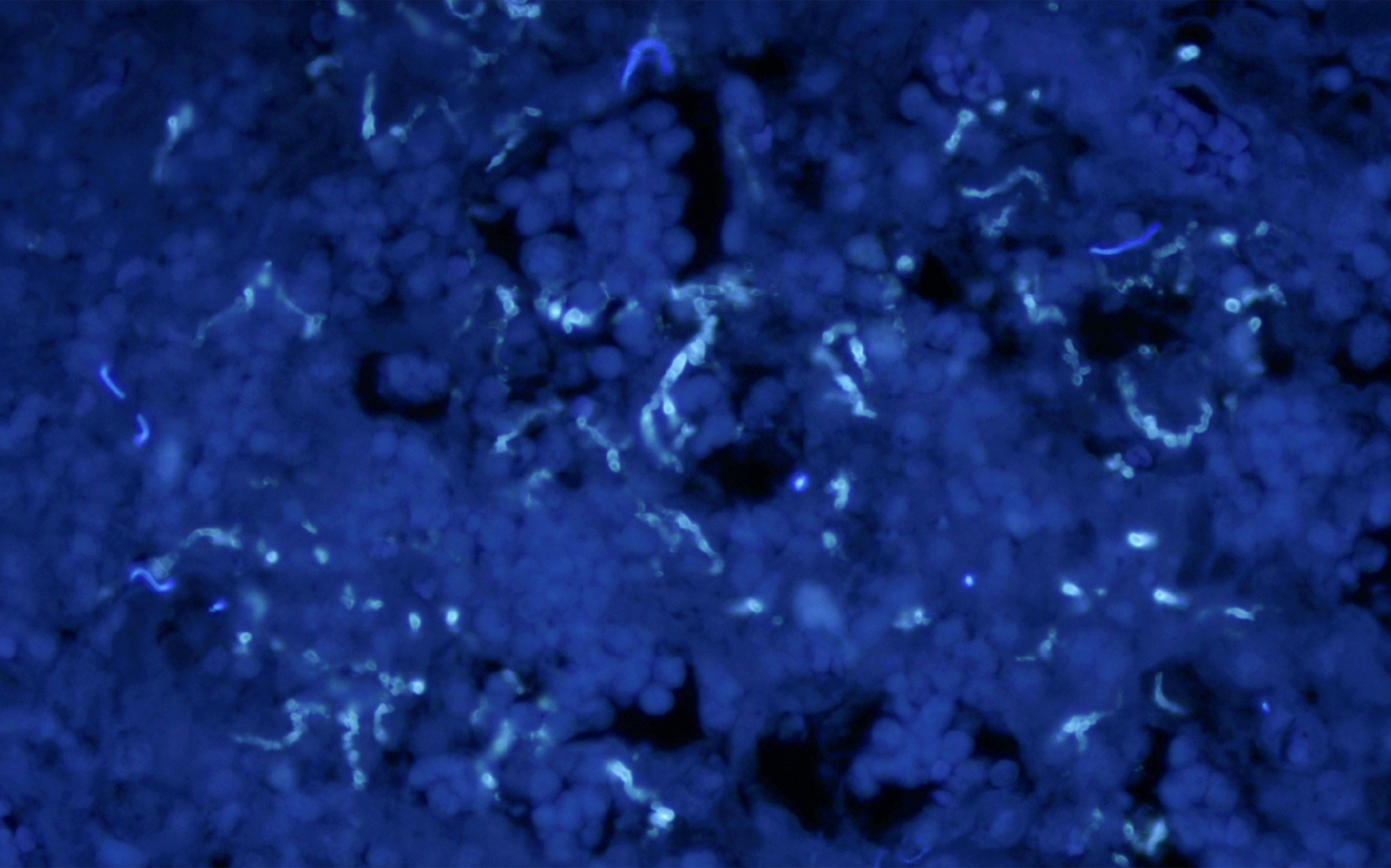

Routine postoperative pathologic examination confirmed myositis and necrosis in the pterygoid muscle. Fungi were detected in the pathological sections of both muscle tissue and surrounding necrotic tissue (Figure 3 and 4). In addition, aspergillosis was diagnosed based on morphological analysis. Therefore, the final diagnosis was amended to fungal myositis in the pterygoid muscle with necrosis.

The patient was prescribed antifungal therapy and mouth opening training. Considering that the original lesion had been resected thoroughly, treatment with oral voriconazole (loading dose, 300 mg bid; maintenance dose, 200 mg bid) was instituted. Voriconazole was discontinued after 8 wk of therapy. No adverse reactions were detected during the treatment. The patient was recommended to perform mouth opening exercises 1 wk postoperatively using a T-shaped mouth opener.

The interincisor distance of the patient increased to 30 mm at 15 d postoperatively. After 6 mo of follow-up, her mouth opening was stable at 36 mm. She did not complain of pain or trismus.

The word trismus was originally used only in tetanus as a prolonged masticatory muscle spasm[1]. However, the term is currently used to indicate varying degrees of restricted mouth opening regardless of the etiology. In most of the studies we reviewed, the authors only set criteria for trismus but did not explain why they defined it in that way. In addition, no study has provided justification for its criteria. Some authors defined trismus as a mouth opening less than an appointed number, while others defined it according to a more gradual scale[2-4]. However, most authors agree that a mouth opening of 35 mm or less should be regarded as a trismus.

Trismus has a negative impact on quality of life. It may impair basic oral functions such as chewing, swallowing, and speech. It also detrimentally affects oral hygiene and tumor surveillance[5-7]. Early diagnosis and treatment have the potential to minimize the consequences of trismus[8].

The identification of the true causes of trismus is complicated. Traditionally, they can be divided into intra-articular or extra-articular, which are often difficult to distinguish. Many causes are related to abnormalities in the masticatory muscles. Malignant diseases in the head and neck area can provoke trismus by infiltration and irritation of the muscles adjacent to the mandibular locomotor structure. Treatment of the malignancy, including surgical resection and radiotherapy, can also lead to trismus by producing muscular fibrosis and muscle contraction[5,9]. Some authors emphasize the impairment of the pterygoid muscles for the development of trismus[10,11]. Although it is widely recognized that pterygoid myositis can give rise to trismus[12], a fungus-originated case is still unexpected.

In general, healthy muscles are resistant to infection[13]. Muscle infection is uncommon, and fungal myositis is even rarer. It is well known that fungal infections are almost totally opportunistic. Fungi turn into pathogens only under the right circumstances[14]. Although fungal myositis is occasionally reported in immunocompetent individuals, most cases involve immunocompromised patients[15-18]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices has identified many possible risk factors for immunodeficient patients. The most common conditions for fungal infection include diabetes, especially cases with ketoacidosis and hematological malignancies with neutropenia. Immune deficiency in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome still plays a controversial role in mycosis generation. Some authors have not considered it a risk factor[19].

The potential routes of fungal myositis are an invasion of the musculature via contiguous sites[20], hematogenous dissemination, and trauma with direct seeding of spores. The use of needles or intravenous catheters as iatrogenic factors has also been reported[21]. In our case, routine blood examination revealed abnormalities in connection with immunocompromise. As fungal myositis is usually recognized as a complication of systemic mycosis[22], blood dissemination may be a reasonable approach in our case.

To our knowledge, there has been a steady increase in the incidence of fungal sinusitis in immunodeficient patients. Currently, fungal sinusitis is divided into two dominant types: Invasive and noninvasive. As its name implies, invasive fungal sinusitis can invade and destroy neighboring tissues.

The diagnosis of invasive fungal sinusitis (IFS) remains difficult. As seen in bacterial or viral sinusitis, early radiologic findings of IFS are nonspecific[16,23]. Sometimes, bone destruction can be seen in the progressive stage. Moreover, acute IFS can disseminate to adjacent structures. However, definitive diagnosis and identification of the species can only be made by fungal culture. In this study, bone destruction of the maxillary sinus back wall was observed. In addition, abnormal mucosal lesions were also observed. Therefore, we could not exclude local invasion as one possible route, although there was no pathological evidence of fungal infection in the maxillary sinus. However, routine histological analysis verified that fungi, most likely Aspergillus, were located in the muscle and necrotic tissue.

For a definite diagnosis of fungal myositis, a timely treatment protocol must be implemented. However, due to its rarity and limited clinical experience, no consensus has been reached regarding the best means of treating it[22,24]. Therefore, the treatment is regularly combined and consists of aggressive surgical debridement and administration of antifungal agents. A distinctive finding during debridement is that the affected tissue did not bleed, presumably because of tissue infarction. Furthermore, therapies to reverse underlying risk factors are recommended for immunocompromised patients, for example, hypodermic injection of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to restore neutrophil counts.

In addition to these etiological treatments specific to fungal infections, there are some conventional symptomatic treatments for trismus. According to many reports, conservative treatment is effective. Exercise is believed to be an indispensable mainstay for different etiogenic trismus. Tongue spatulas, TheraBite Jaw Motion Rehabilitation System™, and Dynasplint Trismus System have presented promising results in clinical use[8,25]. Other conservative treatments, such as thermal therapy, electrotherapy, and botulinum toxin injection, are also optional, but their potential effects are uncertain[26-28]. Finally, it cannot be denied that quality of life deficits originate from trismus results even in social inhibition and depression. Based on this reality, trismus should be treated in an integral way, including measures to sustain patients’ mental health. Simultaneously, we should always remember that prevention, rather than treatment, is the most important objective.

Regardless of fungal myositis or trismus, the prognosis largely depends on early diagnosis and timely treatment. Many factors are associated with the prognosis. Basic immune status, mental status, uncontrolled diabetes, and mouth opening exercises are considered the most important prognostic factors.

The rarity of fungal myositis may be responsible for the misdiagnosis of this case. Although a definitive pathological diagnosis was obtained, the origin of the pathogenic fungi remains unconfirmed. Since the patient was also diagnosed with diabetes, which could erode her immunity, we believed that opportunistic fungal infection was possible. Under these circumstances, both a hematogenous spread and local invasion could be their true origins. Therefore, surgeons should remain vigilant of the possibility of trismus originating from fungal myositis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Vice Chairman of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Committee of Chinese Stomatological Association, No. 51100000500018514J.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta SK S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Tveterås K, Kristensen S. The aetiology and pathogenesis of trismus. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1986;11:383-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sakai S, Kubo T, Mori N, Itoh M, Miyaguchi M, Kitaoku S, Sakata Y, Fuchihata H. A study of the late effects of radiotherapy and operation on patients with maxillary cancer. A survey more than 10 years after initial treatment. Cancer. 1988;62:2114-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bertrand J, Luc B, Philippe M, Philippe P. Anterior mandibular osteotomy for tumor extirpation: a critical evaluation. Head Neck. 2000;22:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chua DT, Lo C, Yuen J, Foo YC. A pilot study of pentoxifylline in the treatment of radiation-induced trismus. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:366-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ren WH, Ao HW, Lin Q, Xu ZG, Zhang B. Efficacy of mouth opening exercises in treating trismus after maxillectomy. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:2666-2669. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Johnson J, Johansson M, Rydén A, Houltz E, Finizia C. Impact of trismus on health-related quality of life and mental health. Head Neck. 2015;37:1672-1679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weber C, Dommerich S, Pau HW, Kramp B. Limited mouth opening after primary therapy of head and neck cancer. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;14:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rapidis AD, Dijkstra PU, Roodenburg JL, Rodrigo JP, Rinaldo A, Strojan P, Takes RP, Ferlito A. Trismus in patients with head and neck cancer: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40:516-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dijkstra PU, Sterken MW, Pater R, Spijkervet FK, Roodenburg JL. Exercise therapy for trismus in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lehman H, Fleissig Y, Abid-el-raziq D, Nitzan DW. Limited mouth opening of unknown cause cured by diagnostic coronoidectomy: a new clinical entity? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:230-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scott B, Butterworth C, Lowe D, Rogers SN. Factors associated with restricted mouth opening and its relationship to health-related quality of life in patients attending a Maxillofacial Oncology clinic. Oral Oncol. 2008;44:430-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kim HY, Chung JW. Infectious Myositis of the Jaw Presenting as Trismus of Unknown Origin. J Oral Med Pain. 2020;45:115-119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zadroga RJ, Zylla D, Cawcutt K, Musher DM, Gupta P, Kuskowski M, Dincer A, Kaka AS. Pneumococcal pyomyositis: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:e12-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Turner JH, Soudry E, Nayak JV, Hwang PH. Survival outcomes in acute invasive fungal sinusitis: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of published evidence. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1112-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ahadian H, Yassaei S, Bouzarjomehri F, Ghaffari Targhi M, Kheirollahi Kh. Oral Complications of The Oromaxillofacial Area Radiotherapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:721-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zaidan M, Ottaviani S, Polivka M, Bouldouyre MA, Orcel P, Richette P. Aspergillus-related myositis: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:230-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thurtell MJ, Chiu AL, Goold LA, Akdal G, Crompton JL, Ahmed R, Madge SN, Selva D, Francis I, Ghabrial R, Ananda A, Gibson J, Chan R, Thompson EO, Rodriguez M, McCluskey PJ, Halmagyi GM. Neuro-ophthalmology of invasive fungal sinusitis: 14 consecutive patients and a review of the literature. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41:567-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Redmann AJ, Myer CM 4th, Khandelwal P, Danzinger-Isakov L. Invasive fungal pharyngitis in a pediatric bone marrow transplant patient. Pediatr Transplant. 2021;e13853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McNab AA. Invasive fungal sinusitis: ophthalmic emergency. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41:521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim BE, Park KJ, Lee JE, Park YJ, Kwon JS, Kim SK, Choi JH, Ahn HJ. Fungal Osteomyelitis of Temporomandibular Joint and Skull Base Caused by Chronic Otitis Media. Oral Med Pain. 2020;45:12-16. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Skiada A, Rigopoulos D, Larios G, Petrikkos G, Katsambas A. Global epidemiology of cutaneous zygomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:628-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lin XJ, Yao RX, He MQ, Zhu BL, Guo WJ. Treatment of fungal myositis with intra-lesional and intravenous itraconazole: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Seo J, Kim HJ, Chung SK, Kim E, Lee H, Choi JW, Cha JH, Kim ST. Cervicofacial tissue infarction in patients with acute invasive fungal sinusitis: prevalence and characteristic MR imaging findings. Neuroradiology. 2013;55:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dijkstra PU, Kalk WW, Roodenburg JL. Trismus in head and neck oncology: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2004;40:879-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Crum-Cianflone NF. Nonbacterial myositis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:374-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stubblefield MD, Manfield L, Riedel ER. A preliminary report on the efficacy of a dynamic jaw opening device (dynasplint trismus system) as part of the multimodal treatment of trismus in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1278-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Stubblefield MD, Levine A, Custodio CM, Fitzpatrick T. The role of botulinum toxin type A in the radiation fibrosis syndrome: a preliminary report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hartl DM, Cohen M, Juliéron M, Marandas P, Janot F, Bourhis J. Botulinum toxin for radiation-induced facial pain and trismus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:459-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |