Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6531

Peer-review started: April 7, 2021

First decision: April 23, 2021

Revised: May 6, 2021

Accepted: June 4, 2021

Article in press: June 4, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 111 Days and 18.3 Hours

Fetal hydrops is a serious condition difficult to manage, often with a poor prognosis, and it is characterized by the collection of fluid in the extravascular compartments. Before 1968, the most frequent cause was the maternal-fetal Rh incompatibility. Today, 90% of the cases are non-immune hydrops fetalis. Multiple fetal anatomic and functional disorders can cause non-immune hydrops fetalis and the pathogenesis is incompletely understood. Etiology varies from viral infections to heart disease, chromosomal abnormalities, hematological and autoimmune causes.

A 38-year-old pregnant woman has neck lymphoadenomegaly, fever, cough, tonsillar plaques at 14 wk of amenorrhea and a rash with widespread itching. At 27.5 wk a fetal ultrasound shows signs of severe anemia and hydrops. Cordo

An attempt to determine the etiology of hydrops should be made at the time of diagnosis because the goal is to treat underlying cause, whenever possible. Even if the infectious examinations are not conclusive, but the pregnancy history is strongly suggestive of infection as in the first case, the infectious etiology must not be excluded. In the second case, instead, transplacental passage of maternal autoantibodies caused hydrops fetalis and severe anemia. Finally, obstetric management must be aimed at fetal support up to an optimal timing for delivery by evaluating risks and benefits to increase the chances of survival without sequelae.

Core Tip: We present herein, two rare cases of non-immune hydrops fetalis with severe fetal anemia. Despite the similar onset, the etiology was infectious in the first case and autoimmune in the last one. In particular, we want to emphasize that even if the infectious examinations are not conclusive, but the pregnancy history is strongly suggestive of infection, the infectious etiology must not be excluded. Secondly, transplacental passage of maternal autoantibodies can cause hydrops fetalis and severe anemia. In any case, obstetric management must always be aimed at fetal support up to an optimal timing for delivery by evaluating risks and benefits.

- Citation: Maranto M, Cigna V, Orlandi E, Cucinella G, Lo Verso C, Duca V, Picciotto F. Non-immune hydrops fetalis: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6531-6537

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6531.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6531

Fetal hydrops (HF) is a serious condition difficult to manage, often with a poor prognosis, and it is characterized by the collection of fluid in the extravascular compartments. In particular, the diagnosis is based on the presence of two or more of the following findings on ultrasound examination: ascites (early sign), skin edema (later sign), pleural effusion, pericardial effusion[1,2].

In 1943, Potter defined two forms of HF: Immunomediated (IHF) and non-immune (NIHF). Before the use of anti-D immune globulin in 1968, the most frequent cause was the maternal-fetal Rh incompatibility, today 90% of the cases are NIHF[3] with a prevalence that ranges from 1 / 1500 to 1 / 4000 births[4-7]. Multiple fetal anatomic and functional disorders can cause NIHF and the pathogenesis is incompletely understood[8]. Etiology varies from viral infections to heart disease, chromosomal abnormalities and hematological causes[9-11].

The purpose of this report is to describe two complex cases of NIHF diagnosed in our center between 2018 and 2019, from prenatal diagnosis to neonatal management. Clinical records and laboratory data have been collected retrospectively analyzing clinical and ultrasound documentation of the mother and child.

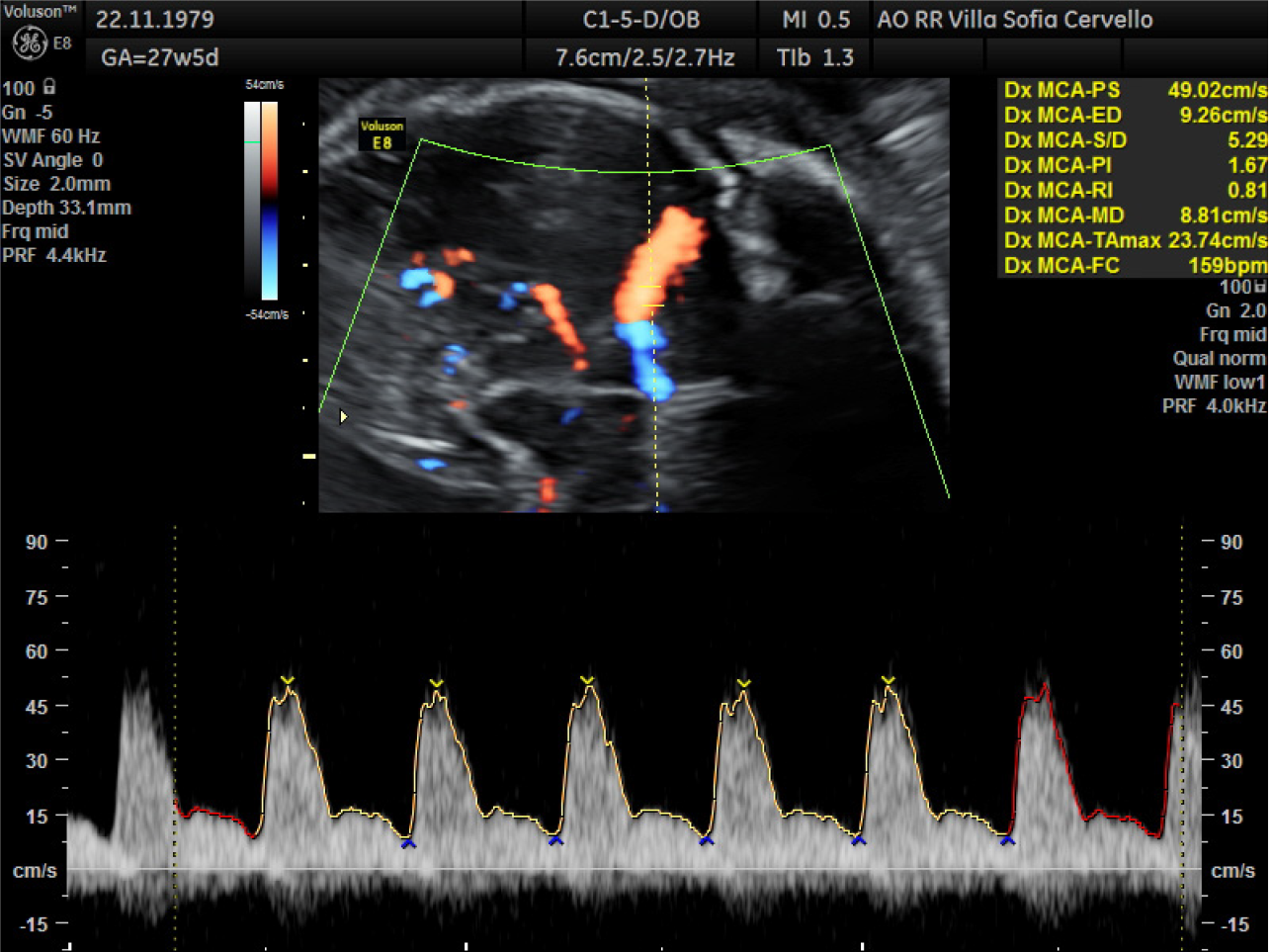

Case 1: At 27.5 wk of amenorrhea a fetal ultrasound showed signs of severe anemia, as shown in Figure 1, and hydrops (ascites, diffuse edema, pericardic effusion, severe cardiomegaly and hepatomegaly).

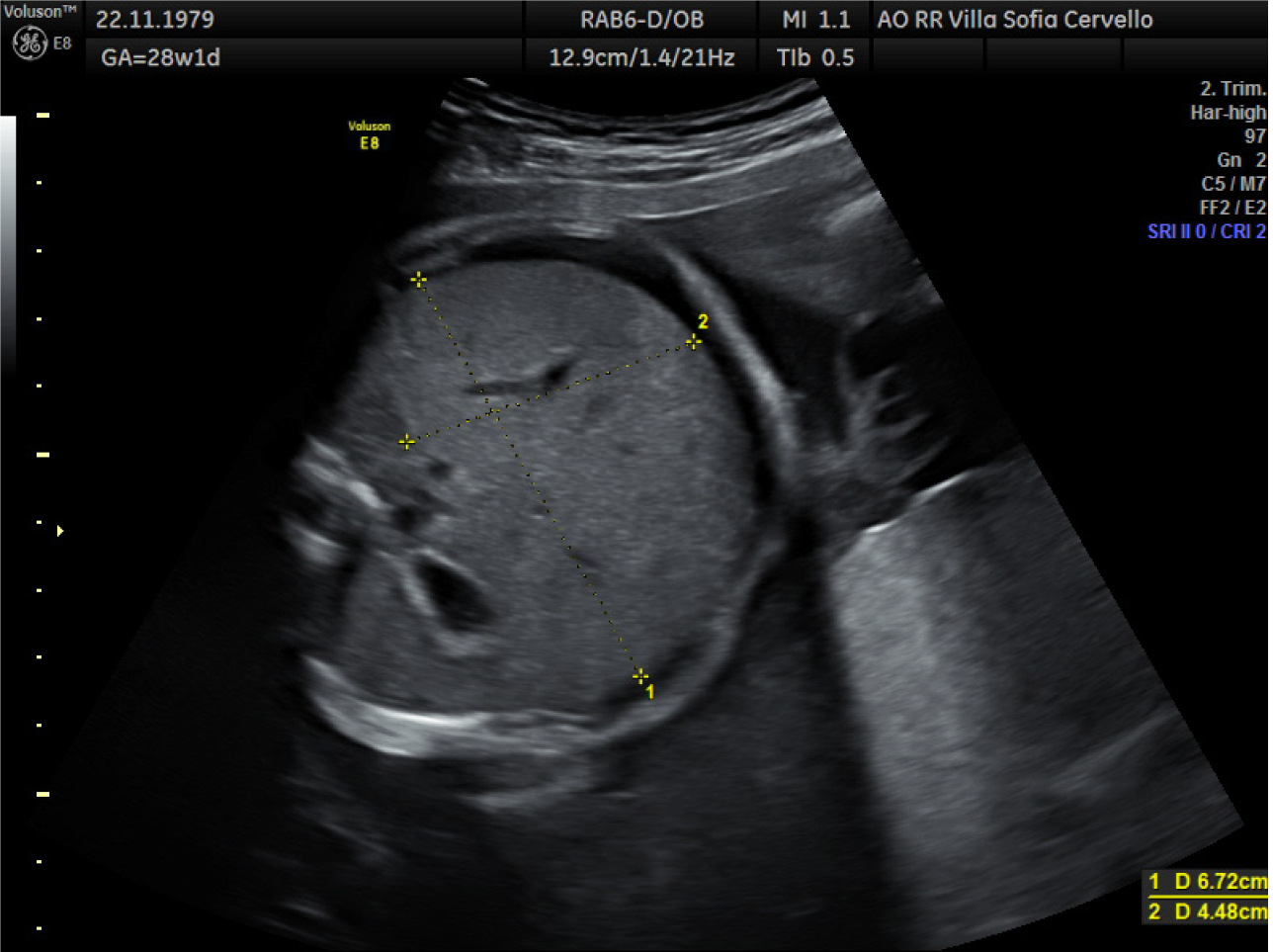

At cordocentesis (shown in Figure 2), fetal hemoglobin (Hb) of 1.77 mmol/L is found, therefore transfusion of concentrated and irradiated red blood cells is performed and an Hb value of 4.37 mmol/L is reached. Moreover karyotype (46, XX), array-comparative genome hybridization (CGH) (negative), and infectious tests are performed on fetal blood: Cytomegalovirus IgG positive and IgM negative, herpes simplex 1 IgG positive and IgM negative, herpes simplex 2 IgG negative and IgM positive, HBsAg negative, hepatitis C virus-DNA negative, Toxoplasma IgG and IgM negative, Epstein-Barr IgG positive and IgM negative, Parvovirus B19 IgG positive and IgM negative. In the following days there was a progressive improvement of the indirect signs of fetal anemia as shown in Figure 3 (resolution of ascites and skin edema and reduction of cardiomegaly). At 31.2 wk reappearance of fetal anemia with Hb 3.29 mmol/L and 2% reticulocytes, second transfusion is performed with achievement of Hb 6.39 mmol/L. At 33.6 wk, for relapse of severe fetal anemia, an urgent cesarean section is performed, with the birth of a female fetus, fetal weight of 2080 g, Apgar 1’: 8, 5’: 9.

Case 2: For Sjogren's syndrome, the patient was subjected to serial fetal ecocardio: The exams were always negative for branch block, but at 26.5 wk there was a finding of fetal ascites. Infectious disease tests on amniotic fluid were negative as well as quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction, Array CGH. At cordocentesis Hb was 1.3 mmol/L, therefore fetal transfusion is performed with Hb 4.34 mmol/L at the end of the procedure. At 27.1 wk, after ultrasound check with indirect diagnosis of severe fetal anemia, another cordocentesis is performed with Hb 2.76 mmol/L; so the second fetal transfusion is performed with the achievement of Hb 5.24 mmol/dL. At 27.6 wk a new ultrasound check is performed with ascites and hydrothorax; fetal ascites drainage (80 mL) to perform lymphocyte count, microvillary enzymes, beta-2-microglobulin. The third fetal transfusion was performed at 28.1 wk for further detection of fetal anemia (Hb 3.66 mmol/L), with Hb of 6.58 mmol/L at the end of the procedure. On the same day, two units of blood cells concentrated to the mother are transfused with maternal Hb from 4.65 mmol/L to 5.9 mmol/L.

Due to the persistence of fetal ascites and fetal anemia, at 29.4 wk a cesarean section is performed, with the birth of a female fetus, fetal weight of 1650 g and Apgar 1’: 7, 5’: 9. The pathological examination is performed on the placenta: the diagnosis was retroplacental hematoma with adaptive modifications to hypoxic suffering.

Case 1: In current pregnancy, the patient performed low-risk first-trimester screening. At 14 wk, she showed neck lymphoadenomegaly, fever, cough, tonsillar plaques, followed by a rash with widespread itching.

Case 2: In current pregnancy, the patient performed low-risk first-trimester screening.

Case 1: Negative medical and obstetric history.

Case 2: She has β-Thalassemia intermedia and Sjogren's syndrome with positive Anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, being treated with prednisone 5 mg/d, acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg/d, calcium nadroparin 3800 UI/d and hydroxychloroquine sulphate 200 mg/d.

Case 1: The first pregnant woman is a 38-year-old Caucasian woman, non-smoker, her blood type is A Rhesus positive.

Case 2: The second patient is a 29-year-old Caucasian woman, non-smoker, her blood type is 0 Rhesus positive.

Case 1: The first case report represents an example of NIHF caused by post-infectious fetal anemia. A diagnosis of exclusion was made, guided by the anamnesis, which highlighted the maternal symptoms between the first and second trimester of pregnancy.

Case 2: The search for autoantibodies in the baby found SS-A Ro60 positive, SSA-Ro52 positive and SS-B negative.

In both cases, prenatal treatment with fetal transfusions by cordocentesis, allowed the survival of fetuses up to an appropriate time for delivery.

Case 1: The newborn needed ventilatory support in n-CPAP mode in the first 10 h of life. On day 12 of hospitalization, for the detection of anemia (Hb 3.91 mmol/L), she was subjected to transfusion of concentrated red blood cells and she began treatment with erythropoietin which was continued up to 4 mo of life. Later on there was a normalization of blood chemistry values and the baby did not need new transfusions. During the hospitalization an ultrasound follow-up was performed: the ecocardium on day 3 of life showed a slight dilation of the right chambers, which gradually decreased.

Case 2: In the first hours of life the patient needed ventilatory assistance, surfactant was administered with the INSURE technique. On day 9 of life treatment with erythropoietin was started, but in the following 2 mo she needed three blood transfusions.

The causes of NIHF are heterogeneous: cardiac, pulmonary, metabolic, hematologic and infectious. Hydrops is associated with an overall perinatal mortality rate from 50% to 98%[2,12]. Even among liveborn infants, mortality is 43% by 1 year of age in one large series[7].

Despite advances in fetal diagnosis and therapy, the mortality rate has not changed substantially in recent years. For this reason it is essential to continue collecting data of this rare, serious and still difficult condition.

In general, early onset, the presence of pleural effusion and polyhydramnios before 20 wk, are poor prognostic factors especially due to the increased risk of pulmonary hypoplasia and preterm delivery. Instead, absence of aneuploidy and absence of major structural abnormalities confer a better prognosis[13,14].

Antenatal management includes etiological diagnosis, whenever possible. If the fetus is anemic, as in the two cases described, transfusions are carried out in the uterus waiting for the timing of delivery. Pregnancy should be managed in third-level center where a close collaboration between obstetricians and neonatologists ensures improved perinatal care.

Postnatal management initially involves stabilization of the newborn; then the goal is to identify the underlying cause and to treat it. Often, due also to pulmonary hypoplasia, these newborns need an invasive ventilatory support at birth and endotracheal intubation can be difficult due to the widespread edema that also involves the oropharynx[15]. Sometimes, these patients also need hemodynamic stabilization, by intravenous fluid infusion or by using inotropic drugs to improve cardiac output. Anemia may be due to hemolysis (thalassemia, hereditary spherocytosis), blood loss from maternal-fetal hemorrhage or reduction in fetal red blood cell production (parvovirus B19 infection). In cases where red blood cell transfusion is required, an isovolemic exchange is preferred so as not to further increase central venous pressure[16].

As described in the literature, NIHF frequently has an infectious etiology, like parvovirus B19, cytomegalovirus, syphilis and toxoplasmosis. These infections can cause fetal anemia with subsequent heart failure, or to myocarditis caused by the pathogens themselves[17]. Recently, two cases of fetal transient skin edema in pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 in their second trimester of pregnancy are described, resolved when maternal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test results became negative. However, it is unclear whether skin edema in these cases was related to maternal infection[18].

The laboratory diagnosis of maternal parvovirus B19 infection is based on the search for specific IgG and IgM antibodies. Circulating IgM antibodies can be detected about 10 d after exposure and immediately before the onset of symptoms, they may persist for 3 mo or more[19]. However, the negativity of anti-parvovirus IgM can be misleading in a patient with a history and a significant clinical history, because in some cases maternal IgM levels may be lower than the detection limit and thus give a false negative, as in case 1.

The clinical cases described represent an example of post-infectious HF, the other an immune-mediated form. The diagnosis was initially oriented by the anamnesis, which highlighted in the first case the maternal symptomatology between the first and the second trimester of pregnancy, and in the other patient the autoimmune pathology. In both cases, follow-up and prenatal treatment allowed fetal survival; the management in a third level center has guaranteed the newborn adequate care at birth, and consequently a complete diagnostic-therapeutic procedure.

Both patients had severe anemia, in the first one caused by post-infectious bone marrow aplasia and the last one of autoimmune nature, both required transfusion of red blood cells both in the prenatal and post-natal periods. However, the hemoglobin values normalized after resolution of the active infection and following the disappearance of maternal autoantibodies, respectively. Follow-up did not detect new episodes of anemia or other disorders.

In conclusion, an attempt to determine the etiology of hydrops should be made at the time of diagnosis, since several etiologies can be confirmed or excluded based upon ultrasound findings. However, the cause of hydrops can be determined prenatally or postnatally in 60%-85% of cases. In the remaining cases the cause rests unknown.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sergi C S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Jones DC. Nonimmune fetal hydrops: diagnosis and obstetrical management. Semin Perinatol. 1995;19:447-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Carlson DE, Platt LD, Medearis AL, Horenstein J. Prognostic indicators of the resolution of nonimmune hydrops fetalis and survival of the fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1785-1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Potter EL. Universal edema of the fetus unassociated with erythroblastosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1943;46:130-134. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sohan K, Carroll SG, De La Fuente S, Soothill P, Kyle P. Analysis of outcome in hydrops fetalis in relation to gestational age at diagnosis, cause and treatment. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:726-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Castillo RA, Devoe LD, Hadi HA, Martin S, Geist D. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis: clinical experience and factors related to a poor outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:812-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Anandakumar C, Biswas A, Wong YC, Chia D, Annapoorna V, Arulkumaran S, Ratnam S. Management of non-immune hydrops: 8 years' experience. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;8:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Steurer MA, Peyvandi S, Baer RJ, MacKenzie T, Li BC, Norton ME, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL, Moon-Grady AJ. Epidemiology of Live Born Infants with Nonimmune Hydrops Fetalis-Insights from a Population-Based Dataset. J Pediatr. 2017;187:182-188.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bellini C, Hennekam RC. Non-immune hydrops fetalis: a short review of etiology and pathophysiology. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Enders M, Weidner A, Zoellner I, Searle K, Enders G. Fetal morbidity and mortality after acute human parvovirus B19 infection in pregnancy: prospective evaluation of 1018 cases. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:513-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Enders M, Klingel K, Weidner A, Baisch C, Kandolf R, Schalasta G, Enders G. Risk of fetal hydrops and non-hydropic late intrauterine fetal death after gestational parvovirus B19 infection. J Clin Virol. 2010;49:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Puccetti C, Contoli M, Bonvicini F, Cervi F, Simonazzi G, Gallinella G, Murano P, Farina A, Guerra B, Zerbini M, Rizzo N. Parvovirus B19 in pregnancy: possible consequences of vertical transmission. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:897-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Santo S, Mansour S, Thilaganathan B, Homfray T, Papageorghiou A, Calvert S, Bhide A. Prenatal diagnosis of non-immune hydrops fetalis: what do we tell the parents? Prenat Diagn. 2011;31:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCoy MC, Katz VL, Gould N, Kuller JA. Non-immune hydrops after 20 weeks' gestation: review of 10 years' experience with suggestions for management. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:578-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Iskaros J, Jauniaux E, Rodeck C. Outcome of nonimmune hydrops fetalis diagnosed during the first half of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wafelman LS, Pollock BH, Kreutzer J, Richards DS, Hutchison AA. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis: fetal and neonatal outcome during 1983-1992. Biol Neonate. 1999;75:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Phibbs RH, Johnson P, Tooley WH. Cardiorespiratory status of erythroblastotic newborn infants. II. Blood volume, hematocrit, and serum albumin concentration in relation to hydrops fetalis. Pediatrics. 1974;53:13-23. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sampath V, Narendran V, Donovan EF, Stanek J, Schleiss MR. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis and fulminant fatal disease due to congenital cytomegalovirus infection in a premature infant. J Perinatol. 2005;25:608-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Garcia-Manau P, Garcia-Ruiz I, Rodo C, Sulleiro E, Maiz N, Catalan M, Fernández-Hidalgo N, Balcells J, Antón A, Carreras E, Suy A. Fetal Transient Skin Edema in Two Pregnant Women With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:1016-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rotbart HA. Human parvovirus infections. Annu Rev Med. 1990;41:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |