Published online Aug 6, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6464

Peer-review started: April 10, 2021

First decision: April 23, 2021

Revised: April 30, 2021

Accepted: May 24, 2021

Article in press: May 24, 2021

Published online: August 6, 2021

Processing time: 108 Days and 21.7 Hours

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an immune-mediated liver disease affecting all age groups. Associations between hepatitis A virus (HAV) and AIH have been described for many years. Herein, we report a case of an AIH/primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) overlap syndrome with anti-HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM) false positivity.

A 55-year-old man was admitted with manifestations of anorexia and jaundice along with weakness. He had marked transaminitis and hyperbilirubinemia. Viral serology was positive for HAV IgM and negative for others. Autoantibody screening was positive for anti-mitochondria antibody but negative for others. Abdominal ultrasound imaging was normal. He was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A. After symptomatic treatment, liver function tests gradually recovered. Several months later, his anti-HAV IgM positivity persisted and transaminase and bilirubin levels were also more than 10 times above of the upper limit of normal. Liver histology was prominent, and HAV RNA was negative. Therefore, AIH/primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) overlap syndrome diagnosis was made based on the “Paris Criteria”. The patient was successfully treated by immuno

This case highlights that autoimmune diseases or chronic or acute infections, may cause a false-positive anti-HAV IgM result because of cross-reacting antibodies. Therefore, the detection of IgM should not be the only method for the diagnosis of acute HAV infection. HAV nucleic acid amplification tests should be employed to confirm the diagnosis.

Core Tip: Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH)/primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) overlap syndrome is the specific clinical manifestation of AIH, which is an immune-mediated liver disease. Environmental factors including viral infections have been documented to externally trigger AIH. The association between hepatitis A virus (HAV) and AIH has been described for many years. But relying solely on anti- HAV immunoglobulin M (IgM) to diagnose acute HAV infection is not adequate. This case highlights that false-positive anti-HAV IgM might be caused by the cross-reaction of antibodies in individuals with autoimmune diseases or chronic or acute infections. HAV nucleic acid amplification can be used more broadly during the diagnosis workup to confirm HAV infection, especially in patients testing positive for anti-HAV IgM with a low cutoff value.

- Citation: Yan J, He YS, Song Y, Chen XY, Liu HB, Rao CY. False positive anti-hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M in autoimmune hepatitis/primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(22): 6464-6468

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i22/6464.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i22.6464

The pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) requires the interaction of epigenetic, environmental, and immunologic factors[1]. The shape of the immune repertoire plays an important role in the program of AIH. Environmental exposures, such as viral infections, are considered a potential trigger for AIH[2]. Some reported cases indicate that hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is among the triggers of AIH[3-6]. However, if the diagnosis of acute HAV infection is solely based on Anti-HAV immunoglobulin (Ig)M, then it may be suspect. We describe herein a case of AIH/primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) overlap syndrome with anti-HAV IgM false positivity.

A 55-year-old man presented to the hepatology clinic of our hospital complaining of manifestations of anorexia and jaundice along with weakness.

The patient’s symptoms started 10 d previously with manifestations of anorexia, jaundice, and weakness, and had worsened over the last 2 d.

The patient had no past medical history.

The patient did not abuse alcohol or substances. There was no family history of liver disease.

The clinical examination revealed that the skin and sclera were jaundiced.

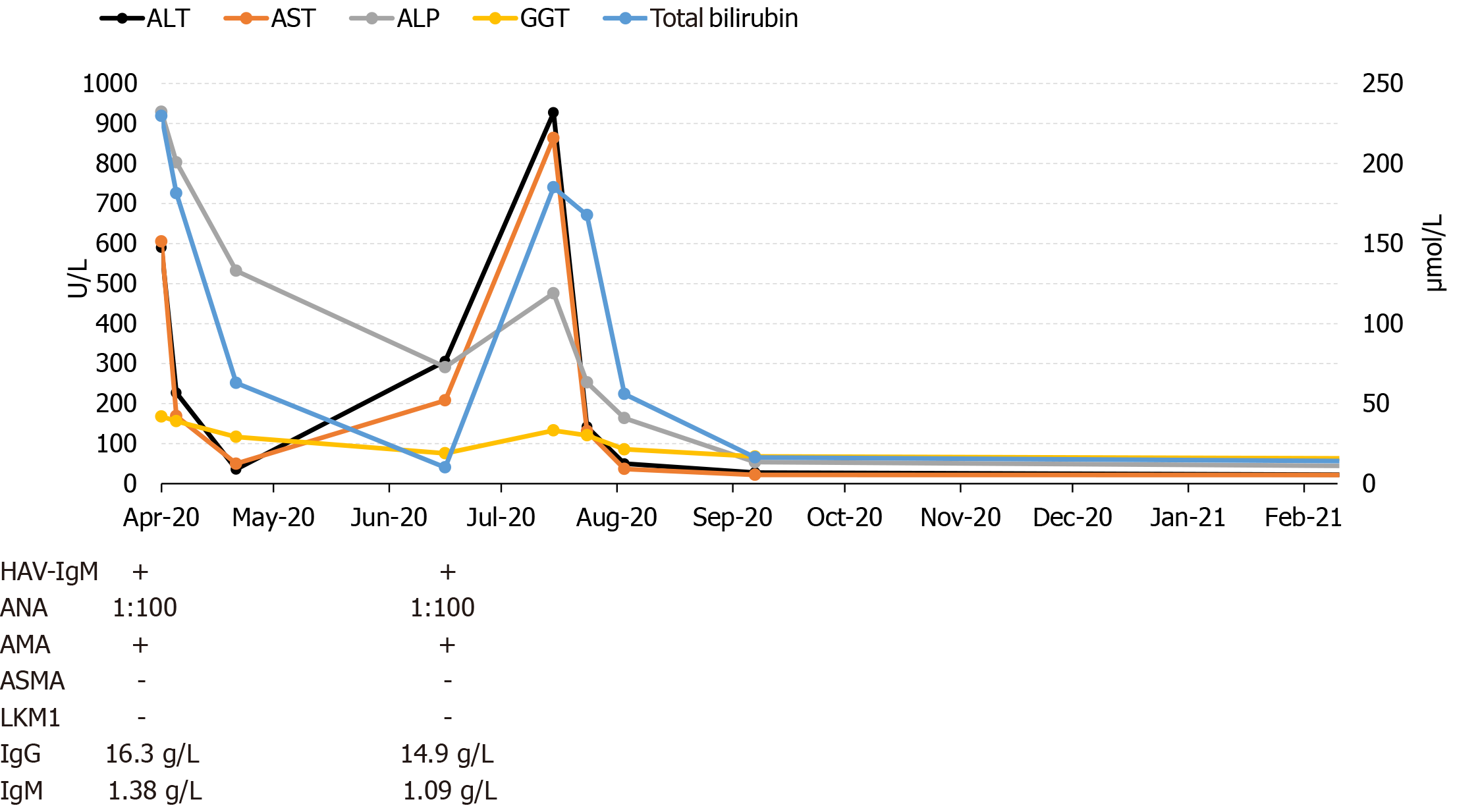

Blood samples revealed (Figure 1) alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 893 U/L, serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 831 U/L, γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase (γ-GGT) 423 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 150 U/L, and total bilirubin 342 μmol/L. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, blood count, triiodothyronine, prothrombin time, and thyroxine were all normal. Serum anti-HAV IgM (1.93) was positive. Other viral serology viral tests were negative. Antibody screening found positive anti-mitochondria antibody (AMA) but negative anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) and anti-liver kidney microsome type 1 (LKM 1). IgA, IgM and IgG levels were normal.

Abdominal ultrasound imaging was normal.

Based on the patient's medical history and evaluation, he was diagnosed with acute hepatitis A (Hep A); PBC could not be excluded. After symptomatic treatment, we discharged the patient on the 20th day of hospitalization with AST 36 U/L, γ-GGT 323 U/L, total bilirubin 62 μmol/L, ALT 50 U/L, and normal ALP and prothrombin time. The patient continued to take ursodeoxycholic acid after discharge.

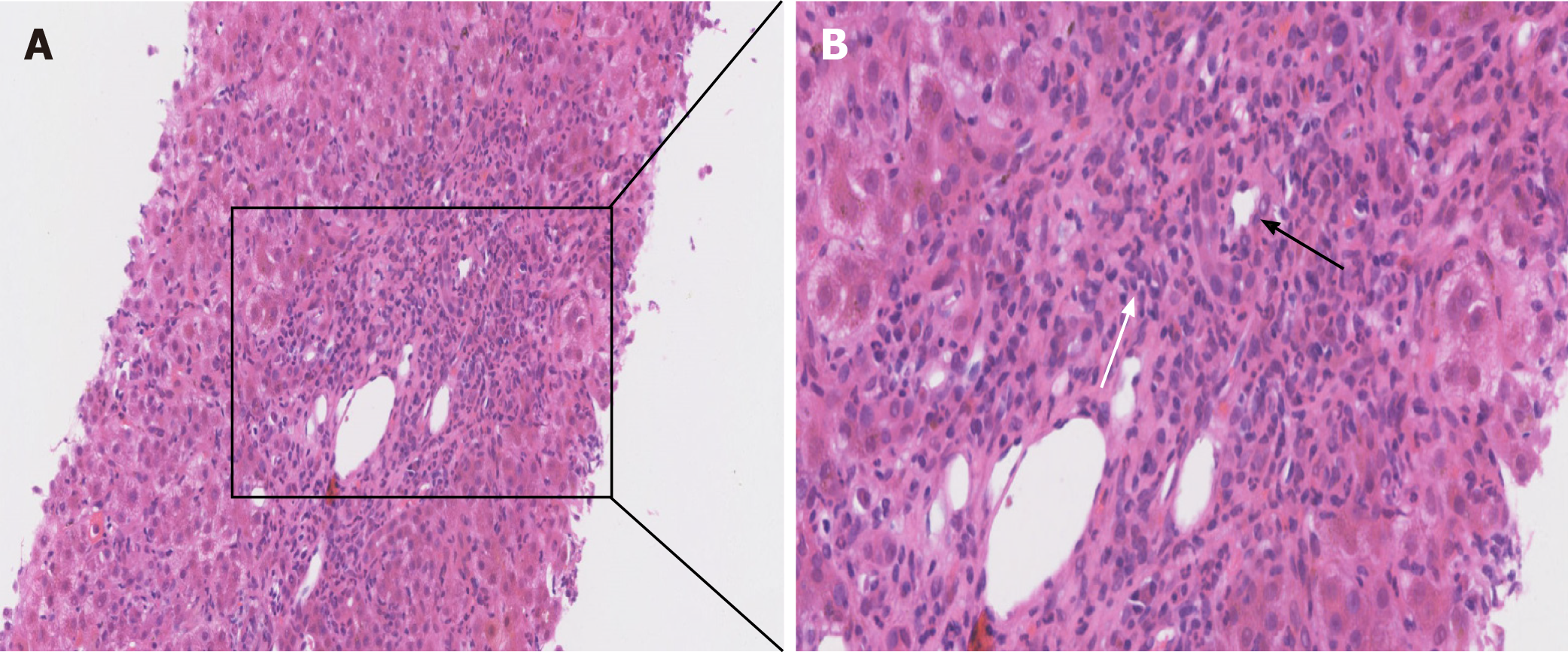

Two months after discharge, his aminotransferase levels began to increase. In the subsequent months, repeated blood examinations revealed ALT 927 U/L, AST 864 U/L, γ-GGT 476 U/L, ALP 133 U/L, and total bilirubin 185 μmol/L. The patient’s serum anti-HAV IgM (3.09) remained positive. Antinuclear antibody (1:100) and AMA were positive while ASMA and anti-LKM were negative. Liver histology showed interface hepatitis accompanied by plasma cell infiltration. Moreover, we observed florid bile duct damage with lymphocytic cholecystitis as shown in Figure 2. Histologic lesions were graded G4S2-3 as per the modified Scheuer score. We also assayed HAV RNA, which was negative.

On the basis of the “Paris Criteria”, AIH/PBC overlap syndrome diagnosis was made, but not acute Hep A.

Treatment with prednisone (30 mg/d) along with ursodeoxycholic acid (15 mg/kg/d), in combination with azathioprine (50 mg/d) after 2 wk was prescribed.

Liver function tests normalized within 50 d. On the 6th month of follow-up, anti-HAV IgM became negative.

HAV infection is commonly self-limiting, with patients completely recovering after about 3 mo. The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A primarily involves serological testing of anti-HAV IgM, which is highly specific and sensitive without testing for the pathogen itself. However, other factors can result in anti-HAV IgM seropositivity in the clinical evaluation[7], potentially leading to an incorrect diagnosis of acute hepatitis A. A Hep A false-positive result might also be caused by the cross-reaction of antibodies in individuals with autoimmune diseases or chronic or acute infections. Polyclonal activation of B lymphocytes can trigger the generation of anti-HAV IgM seropositivity[8]. Therefore, in our case, AIH/PBC overlap syndrome was an immune-triggered inflammatory liver disease that may have caused a false-positive anti-HAV IgM result because of cross-reacting antibodies. There is a report of a false positive hepatitis A serology result in a patient with an acute Epstein-Barr virus infection[9].

In our patient, the anti-HAV IgM result is closely related to the duration from the peak-ALT value to the day of testing[10]. Besides, true positive anti-HAV IgM tests have values that are often 9 to 10 times above the acute HAV cutoff, yet less than four times the cutoff is considered as a false positive result[11]. Our patient had persistent anti-HAV IgM positivity that had a low index of two or three times the cutoff when the ALT values peaked. Therefore, we had to consider that it was a false positive.

An HAV nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) would be an ideal method to confirm positive results when a low anti-HAV IgM level is obtained. Although the time since the manifestation of clinical symptoms can affect the HAV assay result, previous NAAT experience documents that the viremic phase duration is frequently prolonged by more than 2 mo after the initial symptoms of infection[12], and that there is a positive association between HAV RNA and ALT[13]. Unfortunately, there was also no HAV RNA assay to confirm HAV infection in our patient even though ALT had been elevated to 20 times the upper limit of normal. A Hep A diagnosis can be ruled out in the absence of detectable HAV RNA in the serum[14].

Although viral infections can serve as environmental triggers resulting in the loss of self-tolerance to autoantigens in individuals genetically predisposed to AIH[2], and numerous case reports have documented a strong relationship of HAV with the onset of AIH. Anti-HAV IgM testing has proven valuable in the diagnosis of acute HAV infection. However, anti-HAV IgM false positives can result in misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment, therefore the detection of IgM should not be the only method for the diagnosis of acute HAV infection. Other methods, such as NAATs should be employed to confirm the diagnosis, particularly in patients who test positive for anti-HAV IgM with a low cutoff value.

False anti-HAV IgM serological results can lead to misdiagnosis or premature termination of diagnostic tests. Relying solely on anti-HAV IgM to diagnose acute HAV infection is not sufficient. HAV nucleic acid tests can be used more broadly, especially in patients who test positive for anti-HAV IgM with a low cutoff value.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hsu YC, Ogundipe OA S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, Kerkar N, Manns MP, Mayo MJ, Vierling JM, Alsawas M, Murad MH, Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2020;72:671-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 572] [Article Influence: 114.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Taubert R, Diestelhorst J, Junge N, Kirstein MM, Pischke S, Vogel A, Bantel H, Baumann U, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H, Jaeckel E. Increased seroprevalence of HAV and parvovirus B19 in children and of HEV in adults at diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim YD, Kim KA, Rou WS, Lee JS, Song TJ, Bae WK, Kim NH. [A case of autoimmune hepatitis following acute hepatitis A]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tabak F, Ozdemir F, Tabak O, Erer B, Tahan V, Ozaras R. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by the prolonged hepatitis A virus infection. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:177-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singh G, Palaniappan S, Rotimi O, Hamlin PJ. Autoimmune hepatitis triggered by hepatitis A. Gut. 2007;56:304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vento S, Garofano T, Di Perri G, Dolci L, Concia E, Bassetti D. Identification of hepatitis A virus as a trigger for autoimmune chronic hepatitis type 1 in susceptible individuals. Lancet. 1991;337:1183-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alatoom A, Ansari MQ, Cuthbert J. Multiple factors contribute to positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M antibody. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:90-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Desbois D, Grangeot-Keros L, Roquebert B, Roque-Afonso AM, Mackiewicz V, Poveda JD, Dussaix E. Usefulness of specific IgG avidity for diagnosis of hepatitis A infection. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:573-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Valota M, Thienemann F, Misselwitz B. False-positive serologies for acute hepatitis A and autoimmune hepatitis in a patient with acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hyun JJ, Seo YS, An H, Yim SY, Seo MH, Kim HS, Kim CH, Kim JH, Keum B, Kim YS, Yim HJ, Lee HS, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. Optimal time for repeating the IgM anti-hepatitis A virus antibody test in acute hepatitis A patients with a negative initial test. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Landry ML. Immunoglobulin M for Acute Infection: True or False? Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2016;23:540-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fujiwara K, Yokosuka O, Ehata T, Imazeki F, Saisho H, Miki M, Omata M. Frequent detection of hepatitis A viral RNA in serum during the early convalescent phase of acute hepatitis A. Hepatology. 1997;26:1634-1639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee MJ, Sayers AE, Drake TM, Singh P, Bradburn M, Wilson TR, Murugananthan A, Walsh CJ, Fearnhead NS; NASBO Steering Group and NASBO Collaborators. Malnutrition, nutritional interventions and clinical outcomes of patients with acute small bowel obstruction: results from a national, multicentre, prospective audit. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tram J, Le Baccon-Sollier P, Bolloré K, Ducos J, Mondain AM, Pastor P, Pageaux GP, Makinson A, de Perre PV, Tuaillon E. RNA testing for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A during the 2017 outbreak in France. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:540-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |